Abstract

It is well known that the self-employed are over-represented at the bottom as well as the top of the income distribution. This paper shifts the focus from the income situation of the self-employed to the distributive effects of a change in self-employment rates. With representative German data and unconditional quantile regression analysis we show that an increase in the proportion of self-employed individuals in the labor force increases income polarization by tearing down floors at the bottom and allowing higher income potentials at the very top of the hourly income distribution. Recentered influence function regression of inequality measures corroborate that self-employment is a source of income inequality in the labor market.

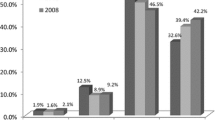

Note: Number of observations: 65. Country codes in accordance with ISO 3166-1 (2digit). Fitted values \( {\widehat{Gini}}\) = 30.3783 + 0.1963 * Self-employment, Robust standard error (0.0346), Corresponding t-statistic 5.67.

Note: x-axis trimmed at hourly income of 60 Euro

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Note that Halvarsson et al. (2018) provide an excellent survey of the literature on entrepreneurship, income dynamics, and inequality.

Empirical studies with German data mostly differ between employers and solo self-employed (Lechmann and Wunder 2017; Sorgner et al. 2017) because information on whether a business is incorporated is usually not available. International studies use this particular distinction as well (Van Stel et al. 2014).

30 days per month divided by 7 days per week.

Freelancers are defined as self-employed as well. Our final sample consists of 480 individuals reporting to be self-employed and 246 freelancers.

\(q_{\tau }\) stands for the hourly income at the quantile of interest (\(\tau \)).

Note that the set of control variables includes 140 dummy variables in accordance with the classification of occupations (KldB10), which describe tasks of a job. This ultimately allows interpretation of the effects as income differentials between self-employed and paid employees in similar jobs.

There is a discussion about comparability of incomes from self-employment and wages of paid employees (Lechmann 2015). Moreover, potential misreporting of incomes from self-employment are debated in the literature (Astebro and Chen 2014). In fact, Astebro and Chen (2014) showed that there is a sizable mean financial gain of entrepreneurship after correcting for misreporting. However, the correction methods heavily rely on the underlying assumptions, which can be ”unpalatable” (Astebro and Chen 2014). In our case, we already observe a meaningful average financial markup for the self-employed (see specification (1) in Table 4). In addition the median income of the self-employed is slightly smaller than the one of paid employees (see specification (3) in Table 4), which indicates that the median self-employed obtains slightly lower hourly incomes when compared with a paid employee with identical characteristics. Hence, systematic income under- or misreporting by the self-employed seems to be no problem in our study.

We are indebted to Philippe Van Kerm for sharing his STATA code to run the command inequaly, which helps to predict a variety of RIFs of a variable (Van Kerm 2015). Precisely, we applied his code for calculation of the RIF of the general entropy index as well as the Atkinson inequality measure.

Caliendo et al. (2012) showed that about 70% of surviving subsidized business founders did not become employers 19 months after the start-up. This pattern is not restricted to subsidized founders. Lechmann and Wunder (2017) found that it is rather unlikely for solo self-employed to become employers. Also other studies showed that the majority of entrepreneurs has low growth ambitions (Hurst and Pugsley 2011) and that entrepreneurship is frequently small scaled rather than taking the form of growing productive and prospering firms (Schoar 2010; Stam 2013).

See Frid et al. (2016) for a discussion of the relationship between entrepreneurship and wealth inequality.

References

Aghion, P., Akcigit, U., Bergeaud, A., Blundell, R., & Hemous, D. (2019). Innovation and top income inequality. The Review of Economic Studies, 86(1), 1–45.

Alejo, J., Gabrielli, M. F., & Sosa-Escudero, W. (2014). The distributive effects of education: An unconditional quantile regression approach. Revista de Analisis Economico - Economic Analysis Review, 29(1), 53–76.

Astebro, T., & Chen, J. (2014). The entrepreneurial earnings puzzle: Mismeasurement or real? Journal of Business Venturing, 29(1), 88–105.

Astebro, T., Chen, J., & Thompson, P. (2011). Stars and misfits: Self-employment and labor market frictions. Management Science, 57(11), 1999–2017.

Atems, B., & Shand, G. (2018). An empirical analysis of the relationship between entrepreneurship and income inequality. Small Business Economics, 51(4), 905–922.

Blanchflower, D. G., & Oswald, A. J. (1998). What makes an entrepreneur? Journal of Labor Economics, 16(1), 26–60.

Borah, B. J., & Basu, A. (2013). Highlighting differences between conditional and unconditional quantile regression approaches through an application to assess medication adherence. Health Economics, 22(9), 1052–1070.

Brenke, K. (2013). Allein tätige Selbständige: Starkes Beschäftigungswachstum, oft nur geringe Einkommen. DIW Wochenbericht, 80(7), 3–16.

Caliendo, M., Hogenacker, J., Künn, S., & Wießner, F. (2012). Alte Idee, neues Programm: Der Gründungszuschuss als Nachfolger von Überbrückungsgeld und Ich-AG. Journal for Labour Market Research, 45(2), 99–123.

Choe, C., & Van Kerm, P. (2018). Foreign workers and the wage distribution: What does the influence function reveal? Econometrics, 6(3), 1–26.

Cowell, F. A., & Van Kerm, P. (2015). Wealth inequality: A survey. Journal of Economic Surveys, 29(4), 671–710.

Firpo, S., Fortin, N. M., & Lemieux, T. (2009). Unconditional quantile regressions. Econometrica, 77(3), 953–973.

Firpo, S. P., Fortin, N. M., & Lemieux, T. (2018). Decomposing wage distributions using recentered influence function regressions. Econometrics, 6(2), 1–40.

Frid, C. J., Wyman, D. M., & Coffey, B. (2016). Effects of wealth inequality on entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 47(4), 895–920.

Fritsch, M., Kritikos, A. S., & Sorgner, A. (2015). Why did self-employment increase so strongly in germany? Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 27(5–6), 307–333.

García-Peñalosa, C., & Orgiazzi, E. (2013). Factor components of inequality: A cross-country study. Review of Income and Wealth, 59(4), 689–727.

Goebel, J., Grabka, M. M., Liebig, S., Kroh, M., Richter, D., Schröder, C., & Schupp, J. (2018). The german socio-economic panel (soep). Jahrbücher für Nationalökonomie und Statistik / Journal of Economics and Statistics.

Halvarsson, D., Korpi, M., & Wennberg, K. (2018). Entrepreneurship and income inequality. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 145, 275–293.

Hamilton, B. H. (2000). Does entrepreneurship pay? an empirical analysis of the returns to self-employment. Journal of Political Economy, 108(3), 604–631.

Hampel, F. R., Ronchetti, E. M., Rousseeuw, P. J., & Stahel, W. A. (1986). Robust statistics: The approach based on influence functions. New York: Wiley.

Hurst, E., & Pugsley, B. W. (2011). What do small businesses do? Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 43(2), 73–142.

Lechmann, D. S. (2015). Can working conditions explain the return-to-entrepreneurship puzzle? Journal for Labour Market Research, 48(4), 271–286.

Lechmann, D. S., & Wunder, C. (2017). The dynamics of solo self-employment: Persistence and transition to employership. Labour Economics, 49, 95–105.

Levine, R., & Rubinstein, Y. (2017). Smart and illicit: Who becomes an entrepreneur and do they earn more? The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 132(2), 963–1018.

Maier, M.F., & Ivanov, B. (2018). Selbstständige Erwerbstätigkeit in Deutschland. Forschungsbericht 514. The German Federal Ministry for Labour and Social Affairs (BMAS).

Metzger, G. (2015). KfW-Gründungsmonitor 2015. KfW Bankengruppe, Frankfurt a. M.: Tabellen- und Methodenband. Technical report.

Moskowitz, T. J., & Vissing-Jorgensen, A. (2002). The returns to entrepreneurial investment: A private equity premium puzzle? The American Economic Review, 92(4), 745–778.

Ritzen, J., & Zimmermann, K. F. (2018). Fading hope and the rise in inequality in the united states. Eurasian Business Review, 8(1), 1–12.

Schoar, A. (2010). The Divide between Subsistence and Transformational Entrepreneurship. In Innovation Policy and the Economy, Vol. 10, PP. 57–81. University of Chicago Press.

Shane, S. (2009). Why encouraging more people to become entrepreneurs is bad public policy. Small Business Economics, 33(2), 141–149.

Sorgner, A., Fritsch, M., & Kritikos, A. (2017). Do entrepreneurs really earn less? Small Business Economics, 49(2), 251–272.

Stam, E. (2013). Knowledge and entrepreneurial employees: A country-level analysis. Small Business Economics, 41(4), 887–898.

Van Stel, A., Wennekers, S., & Scholman, G. (2014). Solo self-employed versus employer entrepreneurs: Determinants and macro-economic effects in oecd countries. Eurasian Business Review, 4(1), 107–136.

Van Kerm, P. (2015). Influence functions at work. In United Kingdom Stata Users’ Group Meetings 2015, Stata Users Group.

Wagner, G. G., Frick, J. R., & Schupp, J. (2007). The german socio-economic panel study (soep)—scope, evolution and enhancements. Schmollers Jahrbuch: Journal of Applied Social Science Studies, 127(1), 139–169.

Acknowledgements

I have benefited from comments by Olaf Hübler, Daniel Lechmann, Wim Naudé, Konrad Schäfer, and participants at the 28th EBES conference in Coventry.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This study is based on The German Socio-Economic Panel Study (SOEP, https://doi.org/10.5684/soep.v32) from the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW Berlin). The author’s program codes will be provided upon request. Any errors are my own. The author has no relevant or material financial interests that relate to the research described in this paper.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schneck, S. Self-employment as a source of income inequality. Eurasian Bus Rev 10, 45–64 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40821-019-00143-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40821-019-00143-8