Abstract

This study analyzes the nonlinear price pattern and its underlying source of nonlinearity for U.S. housing markets along with the plausible explanations of chaos and bubble-like characteristics during 1987 to 2019. The results from the BDS test show evidence of nonlinear dependence in overall U.S. housing markets along with home markets in twenty cities. The K-map Z-map analysis shows that nonlinear dependence in all cities is consistent with chaotic behavior. The nonlinear dependence is also substantiated with the use of Markov chain test where nonlinearity is due to the persistence of either positive or negative returns. Applying the duration dependence test on positive runs confirms that housing markets in all five regions experience some episodes of bubbles, except for home markets in Detroit and Minneapolis in Midwest region. A time reversibility test further provides supporting evidence that the mechanism generating nonlinear dependence in housing markets in all four cities in Midwest region comes from non-Gaussian innovations. Similar finding is reported in housing markets in other regions including Atlanta, Charlotte, Dallas, San Diego, and San Francisco, suggesting that a linear function with non-Gaussian error terms is appropriate for modelling these housing markets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

According to Devaney (1989), chaos process has three conditions. The chaos dynamics are highly dependent on the initial starting point and topologically transitive with many periodic orbits close to each other.

The study period for K-map and Z-map analysis is different from other tests due to the limited data on economic condition index variable. The study period runs from February 1990 to March 2019 for all cities except for Detroit (1991:01), Atlanta (1991:01), and Dallas (2000:01).

The 15 variables used in economic condition index calculation include average weekly hours worked, unemployment rate, all goods-producing employees, all private service-producing employees, all government employees, real average hourly earnings, construction permits for new private residential buildings, real average quarterly wages per employee, total real personal income per capita, industrial availability rate, office vacancy rate, return on average assets, net interest margin, loan loss reserve ratio, and gross metropolitan product.

As indicated by Evans (1991), the finding of bubble could be the result of omitting the important fundamental variables. Therefore, the empirical results from the use of cointegration test for bubbles is questionable as it is subject to testing joint null hypothesis of bubbles and model specification.

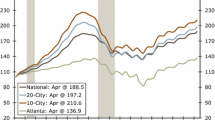

The standard deviations of housing returns for 20 cities in our study are about 82%. However, if we average the returns of housing in 20 cities across each month, the standard deviation is reduced to 61%, which is close to standard deviation of U.S. National Home Price Index of 65%. This verifies that standard deviation decreases significantly in aggregate data, which can be attributable to the loss of information when data is aggregated. This is expected because the correlations among home price indexes from different cities are not perfectly positive. The highest correlation between home price index of Los Angeles and San Diego is 0.88, while the average correlation of home price index is 0.51 between two random cities.

The duration dependence showed a negative hazard rate in negative runs across all cities except for Denver, CO and San Francisco, CA, suggesting that negative returns tend to persist. This result substantiated the findings of persistence in negative returns by Markov Chain test. To conserve space, the results are available from authors upon request.

References

Acemoglu D, Ozdaglar A, Tahbaz-Salehi A (2007) The growth of house prices in Australian capital cities: what do economic fundamentals explain? Aust Econ Hist 40(3):225–238

Arias M, Gascon C, Rapach D (2016) Metro business cycles. J Urban Econ 94:90–108

Asal M (2019) Is there a bubble in the swedish housing market? J Eur Real Estate Res 12(1):32–61

Belke A, Marcel W (2005) Boom or bubble in the US real estate market? Intereconomics 40(5):273–284

Besarria C, Paes N, Silva M (2018) Testing for bubbles in housing markets: some evidence for Brazil. Int J Hous Markets Anal 11(2):754–770

Broock W, Scheinkman J, Dechert W, LeBaron B (1996) A test for independence based on the correlation dimension. Economet Rev 15(3):197–235

Cannon S, Miller N, Pandher G (2006) Risk and return in the U.S. housing market: a cross-sectional asset-pricing approach. Real Estate Econ 34(4):519–552

Caraiani P (2014) What drives the nonlinearity of time series: a frequency perspective. Econ Lett 125(1):40–42

Devaney R (1989) An Introduction to Chaotic Dynamical Systems, 2nd edn. Addison-Wesley

Emekter R, Jirasakuldech B, Went P (2012) Rational speculative bubbles and commodities markets: application of duration dependence test. Appl Financ Econ 22(7):581–596

Enders W, Siklos P (2001) Cointegration and threshold adjustment. J Bus Econ Stat 19(2):166–176

Engelhardt G (2003) Nominal Loss aversion, housing equity constraints, and household mobility: evidence from the United States. J Urban Econ 53(1):171–195

Engsted T, Hviid S, Pedersen T (2016) Explosive bubbles in house prices? Evidence from the OECD countries. J Int Financ Markets Inst Money 40(C):14–25

Evans G (1991) Pitfalls in testing for explosive bubbles in assets price. Am Econ Rev 81(4):922–930

Gallagher E (2019) All recessions are not equal: The effect of sectoral shifts on unemployment using regional data. CMC Senior Theses. 2261. https://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/2261

Genesove D, Mayer C (2001) Loss aversion and seller behavior: evidence from the housing market. Q J Econ 116(4):1233–1260

Hepsen A, Kalfa N (2009) Housing market activity and macroeconomic variables: an analysis of turkish dwelling market under new mortgage system. Istanbul Univ J School Bus Adm 38(1):38–46

Herring R, Wachter S (2002) Bubbles in Real Estate Markets. Zell/Lurie Center Working Papers #402, Wharton School Samuel Zell and Robert Lurie Real Estate Center, University of Pennsylvania

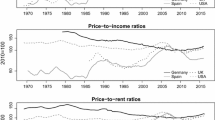

Himmelberg C, Mayer C, Sinai T (2005) Assessing high house prices: bubbles, fundamentals, and misperceptions. J Econ Perspect 19(4):67–92

Hott C (2012) The influence of herding behavior on house prices. J Eur Real Estate Res 5(3):177–198

Hsieh D (1991) Chaos and nonlinear dynamics: application to financial markets. J Financ 46(5):1839–1877

Huang M (2013) The role of people’s expectation in the recent US housing boom and bust. J Real Estate Financ Econ 46(3):452–479

Jirasakuldech B, Emekter R, Went P (2006) Rational speculative bubbles and duration dependence in exchange rates: an analysis of five currencies. Appl Financ Econ 16:233–243

Kim S, Bhattacharya R (2009) Regional housing prices in the USA: an empirical investigation of nonlinearity. J Real Estate Financ Econ 38(4):443–460

Larrain M (1991) Testing chaos and nonlinearities in t-bill rates. Financ Anal J 47(5):51–62

Lehkonen H (2010) Bubbles in China. Int Rev Financ Anal 19(2):113–117

Leung C, Ng C (2019) Macroeconomic Aspects of Housing. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Economics and Finance (Oxford Research Encyclopedias). Oxford University Press

Lim KP, Brooks R (2011) The evolution of stock market efficiency over time: a survey of the empirical literature. J Econ Surv 25(1):69–108

May R (1976) Simple mathematical models with very complicated dynamics. Nature 261(5560):459–467

Maynou L, Monfort M, Morley B, Ordóñez J (2021) Club convergence in European housing prices: the role of macroeconomic and housing market fundamentals. Econ Model 103:1–12

McCarthy J, Peach R (2004) are home prices the next ‘bubble’? Fed Reserve Bank N Y Econ Policy Rev 10(3):1–17

McQueen G, Thorley S (1994) Bubbles, stock returns, and duration dependence. J Financ Quant Anal 29(3):379–401

McQuenn G, Thorley S (1991) Are stock returns predictable? A test using markov chains. J Financ 46(1):239–263

Mikhed V, Zemcik P (2007) Testing for bubbles in housing markets: a panel data approach. J Real Estate Financ Econ 38(4):366–386

Miles W (2008) Boom-bust cycles and the forecasting performance of linear and non-linear models of house prices. J Real Estate Financ Econ 36(3):249–264

Mill E (1989) Social returns to housing and other fixed capital. AREUEA J 17(Summer):197–211

Muellbauer J, Murphy A (1997) Booms and busts in the UK housing market. Economic Journal 107(445):1720–1746

Nartea GV, Cheema MA (2014) Bubble footprints in the Malaysian stock market: are they rational? Int J Account Inf Manag 22(3):223–236

Nartea GV, Cheema MA, Szulczyk K (2017) Searching for rational bubble footprints in the Singaporean and Indonesian stock markets. J Econ Financ 41:529–552

Otto G (2007) The growth of house prices in Australian capital cities: what do economic fundamentals explain? Aust Econ Rev 40(3):225–238

Peng T (2016) The effect of quality determinants on house prices of eight capital cities in australia a dynamic panel analysis. Int J Hous Mark Anal 9 (3): 355–375. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJHMA-06-2015-0028

Peng C, Tsai I (2019) The Influences of Housing Prices on Residential Mobility and Unemployment. European Real Estate Society. https://ideas.repec.org/p/arz/wpaper/eres2019_136.html. Accessed 15 May 2022

Ramsey J, Rothman P (1996) Time reversibility and business cycle asymmetry. J Money Credit Bank 28(1):1–21

Rosenthal S (1999) Residential building and the cost of construction: new evidence on the efficiency of the housing market. Rev Econ Stat 81(2):288–302

Seslen T (2004) Housing Price Dynamics and Household Mobility Decisions. Paper presented at the USC LUSK/FBE Real Estate Seminar

Shi S, Valadkhani A, Smyth R, Vahid F (2016) Dating the timeline of house price bubbles in australian capital cities. Econ Record 92(299):590–605

Shiller R (2005) Irrational Exuberance, 2nd edn. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Skalin J, Teräsvirta T (2002) Modelling asymmetries and moving equilibria in unemployment rates. Macroecon Dyn 6(2):202–241

Stevenson S (2008) Modeling housing market fundamentals: empirical evidence of extreme market conditions. Real Estate Econ 36(1):1–29

Stevenson S, Young J (2014) A Multiple error-correction model of housing supply. Hous Stud 29(3):362–379

Trindade A, Zhu Y, Andrews B (2010) Time series models with asymmetric laplace innovations. J Stat Comput Simul 80(12):1317–1333

Watanapalachaikul S (2021) The impact of COVID-19 Pandemic toward asian pacific stock markets during year 2020: an empirical study of logarithmic returns and duration dependence test model. J Pacific Inst Manag Sci 19(2):113–117

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Jirasakuldech, B., Emekter, R. & Bui, T. Non-linear structures, chaos, and bubbles in U.S. regional housing markets. J Econ Finan 47, 63–93 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12197-022-09598-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12197-022-09598-4