Abstract

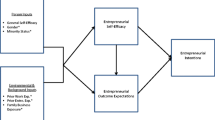

Motivated by the poorly understood nature of the term “mindsets” in the domain of entrepreneurship, we embarked on an exploration encompassing three research goals: a) defining and assessing growth mindsets in entrepreneurship, b) investigating how growth mindsets in entrepreneurship correlate with personality constructs, and c) exploring how growth mindsets predict motivation related to being an entrepreneur. Overall, findings from a sample of entrepreneurs (n = 264) and non-entrepreneurs (n = 330) reveal evidence consistent with the inference that a unidimensional, ‘growth mindset in entrepreneurship’ (GME) construct underlies five distinct mindset measures closely related to entrepreneurship: mindsets of leadership, mindsets of creativity, person mindsets, mindsets of intelligence, and mindsets of entrepreneurial ability. This GME construct correlated positively with conscientiousness and openness (albeit with small effects), but did not consistently correlate with extraversion, agreeableness, or neuroticism. We also found significant and positive relations for the GME with resilience and need for achievement, but a significant (and unexpected) negative correlation with risk-taking. With respect to motivation (operationalized via expectancy-value theory), GME predicted self-efficacy, but only for individuals who did not identify as entrepreneurs. GME exhibited limited utility in predicting enjoyment, utility, or identity evaluations related to value, but was robustly linked to cost evaluations. We discuss the implications of these findings and suggest directions for future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

We have numerous files available on Open Science Framework (OSF; anonymized for review). Our data and measures can be found here: https://osf.io/gu4sc/?view_only=d3b1f3f480dd4a22ab8e6b74c35411ea.

Notes

Two items—one from the leadership scale and one from the intelligence scale—were deleted because their wording was directionally opposite that of the other 13 items, substantially reducing scale reliability (and in the case of the intelligence item, not exhibiting metric invariance across entrepreneurs vs. non-entrepreneurs).

OSF repository: https://osf.io/gu4sc/?view_only=d3b1f3f480dd4a22ab8e6b74c35411ea

Statistical significance for the difference in indirect effects was determined by examining the index of moderated mediation (Hayes, 2018) in all three models. For each dimension of value, the index of moderated mediation significantly differed from zero based on bootstrapped confidence intervals (for Identity Value it was −0.13, 95% CI [−0.24, −0.01]; for Interest/Enjoyment: −.09, 95% CI [−0.17. -0.003]; for Cost: 0.05, 95% CI [0.01, 0.10].

References

Aronson, J., Fried, C. B., & Good, C. (2002). Reducing the effects of stereotype threat on African American college students by shaping theories of intelligence. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 38(2), 113–125.

Anderson, B. S., Wennberg, K., & McMullen, J. S. (2019). Enhancing quantitative theory-testing entrepreneurship research. Journal of Business Venturing, 34(5), 105928.

Audretsch, D. B., Obschonka, M., Gosling, S. D., & Potter, J. (2017). A new perspective on entrepreneurial regions: Linking cultural identity with latent and manifest entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 48(3), 681–697.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215.

Belmi, P., & Pfeffer, J. (2015). How “organization” can weaken the norm of reciprocity: The effects of attributions for favors and a calculative mindset. Academy of Management Discoveries, 1(1), 36–57.

Borsboom, D., Rhemtulla, M., Cramer, A. O. J., van der Maas, H. L. J., Scheffer, M., & Dolan, C. V. (2016). Kinds versus continua: A review of psychometric approaches to uncover the structure of psychiatric constructs. Psychological Medicine, 46, 1567–1579.

Brcic, J., & Latham, G. (2016). The effect of priming affect on customer service satisfaction. Academy of Management Discoveries, 2(4), 392–403.

Brown, T. A. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research, 2nd Ed. The Guilford Press.

Bullough, A., Renko, M., & Myatt, T. (2014). Danger zone entrepreneurs: The importance of resilience and self–efficacy for entrepreneurial intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38(3), 473–499.

Burnette, J. L., Hoyt, C. L., Russell, V. M., Lawson, B., Dweck, C. S., & Finkel, E. (2020a). A growth mind-set intervention improves interest but not academic performance in the field of computer science. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 11(1), 107–116.

Burnette, J. L., O'Boyle, E. H., VanEpps, E. M., Pollack, J. M., & Finkel, E. J. (2013). Mind-sets matter: A meta-analytic review of implicit theories and self-regulation. Psychological Bulletin, 139(3), 655–701.

Burnette, J. L., Pollack, J. M., Forsyth, R. B., Hoyt, C. L., Babij, A. D., Thomas, F. N., & Coy, A. E. (2020b). A growth mindset intervention: Enhancing students’ entrepreneurial self-efficacy and career development. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 44(5), 878–909.

Burnette, J. L., Pollack, J. M., & Hoyt, C. L. (2010). Individual differences in implicit theories of leadership ability and self-efficacy: Predicting responses to stereotype threat. Journal of Leadership Studies, 3(4), 46–56.

Chan, C. R., & Parhankangas, A. (2017). Crowdfunding innovative ideas: How incremental and radical innovativeness influence funding outcomes. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 41(2), 237–263.

Carland III, J. W., Carland Jr., J. W., Carland, J. A. C., & Pearce, J. W. (1995). Risk taking propensity among entrepreneurs, small business owners and managers. Journal of Business and Entrepreneurship, 7(1), 15.

Chen, S., Ding, Y., & Liu, X. (2021). Development of the growth mindset scale: Evidence of structural validity, measurement model, direct and indirect effects in Chinese samples. Current Psychology, 1–15.

Chen, S., Su, X., & Wu, S. (2012). Need for achievement, education, and entrepreneurial risk-taking behavior. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 40(8), 1311–1318.

Cheung, J. H., Burns, D. K., Sinclair, R. R., & Sliter, M. (2017). Amazon mechanical Turk in organizational psychology: An evaluation and practical recommendations. Journal of Business and Psychology, 32(4), 347–361.

Chmielewski, M., & Kucker, S. C. (2020). An MTurk crisis? Shifts in data quality and the impact on study results. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 11(4), 464–473.

Costello, A. B., & Osborne, J. (2005). Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Practical assessment, research, and evaluation, 10(1), 7.

Davis, M. H., Hall, J. A., & Mayer, P. S. (2016). Developing a new measure of entrepreneurial mindset: Reliability, validity, and implications for practitioners. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 68(1), 21–48.

Dibrell, C., Craig, J., & Hansen, E. (2011). Natural environment, market orientation, and firm innovativeness: An organizational life cycle perspective. Journal of Small Business Management, 49(3), 467–489.

Dixson, D. D. (2019). Is grit worth the investment? How grit compares to other psychosocial factors in predicting achievement Current Psychology, 1–8.

Dodge, H. R., & Robbins, J. E. (1992). An empirical investigation of the organizational life cycle. Journal of Small Business Management, 30(1), 27.

Donohoe, C., Topping, K., & Hannah, E. (2012). The impact of an online intervention (Brainology) on the mindset and resiliency of secondary school pupils: A preliminary mixed methods study. Educational Psychology, 32(5), 641–655.

Dweck, C. S. (2000). Self-theories: Their role in motivation, personality, and development. Psychology Press.

Dweck, C. S., Chiu, C. Y., & Hong, Y. Y. (1995). Implicit theories and their role in judgments and reactions: A word from two perspectives. Psychological Inquiry, 6(4), 267–285.

Dweck, C. S., & Leggett, E. L. (2000). A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. In E. T. Higgins & A. W. Kruglanski (Eds.), Key reading in social psychology. Motivational science: Social and personality perspectives (p. 394–415). Psychology Press.

Eccles, J. S. (2005). Subjective task value and the Eccles et al. model of achievement-related choices. In A. S. Elliot & C. S. Dweck (Eds.), Handbook of competence and motivation (pp. 105–121). The Guildford Press.

Eccles, J. S., Adler, T. F., Futterman, R., Goff, S. B., Kaczala, C. M., Meece, J. L., et al. (1983). Expectancies, values, and academic behaviors. In J. T. Spence (Ed.), Achievement and achievement motives: Psychological and sociological approaches (pp. 75–138). W.H. Freeman and Company.

Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (2002). Motivational beliefs, values, and goals. Annual Review of Psychology, 53(1), 109–132.

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191.

Flake, J. K., Barron, K. E., Hulleman, C., McCoach, B. D., & Welsh, M. E. (2015). Measuring cost: The forgotten component of expectancy-value theory. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 41, 232–244.

Flora, D. B. (2018). Statistical methods for the social and Behavioural sciences: A model-based approach. Sage Publication Ltd..

Gunia, B. C., Gish, J. J., & Mensmann, M. (2021). The weary founder: Sleep problems, ADHD-like tendencies, and entrepreneurial intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 45(1), 175–210.

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to moderation, mediation, and conditional process analysis , 2nd Ed. The Guilford Press.

Haynie, J. M., Shepherd, D., Mosakowski, E., & Earley, P. C. (2010). A situated metacognitive model of the entrepreneurial mindset. Journal of Business Venturing, 25(2), 217–229.

Hubner, S., Baum, M., & Frese, M. (2019). Contagion of entrepreneurial passion: Effects on employee outcomes. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 1042258719883995.

Jackson, D. N. (1976). Jackson personality inventory manual. Research Psychologists Press.

Katz-Buonincontro, J., Hass, R., & Reiter-Palmon, R. (2016). To create or not to create? That is the question: Students' beliefs about creativity. AERA Online Paper Repository.

Kirkpatrick, D. L. (1959). Techniques for evaluating training programs. Journal of the American Society of Training Directors, 13(11), 3–9.

Kirkpatrick, D. L., & Kirkpatrick, J. D. (2006). Evaluating training programs: The four levels (3rd edition). Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Kuratko, D. F., Fisher, G., & Audretsch, D. B. (2020). Unraveling the entrepreneurial mindset. Small Business Economics, 1–11.

Lenhard, W. & Lenhard, A. (2016). Calculation of effect sizes. Retrieved from: https://www.psychometrica.de/effect_size.html. Dettelbach (Germany): Psychometrica. DOI: https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.17823.92329. Accessed 15 Jun 2021.

Loewenstein, J., & Mueller, J. (2016). Implicit theories of creative ideas: How culture guides creativity assessments. Academy of Management Discoveries, 2(4), 320–348.

Lundmark, E., & Westelius, A. (2019). Antisocial entrepreneurship: Conceptual foundations and a research agenda. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 11, e00104.

Maula, M., & Stam, W. (2019). Enhancing rigor in quantitative entrepreneurship research. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 1042258719891388.

McGrath, R. G., MacMillan, I. C., & Scheinberg, S. (1992). Elitists, risk-takers, and rugged individualists? An exploratory analysis of cultural differences between entrepreneurs and non-entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing, 7(2), 115–135.

Meehl, P. E. (1992). Factors and taxa, traits and types, differences of degree and differences in kind. Journal of Personality, 60, 117–174.

Murnieks, C. Y., Cardon, M. S., & Haynie, J. M. (2020). Fueling the fire: Examining identity centrality, affective interpersonal commitment and gender as drivers of entrepreneurial passion. Journal of Business Venturing, 35(1), 105909.

Murphy, P. J., Pollack, J., Nagy, B., Rutherford, M., & Coombes, S. (2019). Risk tolerance, legitimacy, and perspective: Navigating biases in social enterprise evaluations. Entrepreneurship Research Journal, 9(4).

Orvidas, K., Burnette, J. L., & Russell, M. (2018). Mindsets applied to fitness: Growth beliefs predict exercise efficacy, value and frequency. Psychology of Sports and Exercise, 36, 156–161.

Pidduck, R. J., Busenitz, L. W., Zhang, Y., & Moulick, A. G. (2020). Oh, the places you’ll go: A schema theory perspective on cross-cultural experience and entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 14, e00189.

Pollack, J. M., Burnette, J. L., & Hoyt, C. L. (2012). Self-efficacy in the face of threats to entrepreneurial success: Mindsets matter. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 34, 287–294.

R Core Team. (2017). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Retrieved from https://www.R-project.org/. Accessed 15 Jun 2021.

Rammstedt, B., & John, O. P. (2007). Measuring personality in one minute or less: A 10-item short version of the big five inventory in English and German. Journal of Research in Personality, 41(1), 203–212.

Rege, M., Hanselman, P., Solli, I. F., Dweck, C. S., Ludvigsen, S., Bettinger, E., Crosnoe, R., Muller, C., Walton, G., Duckworth, A., & Yeager, D. S. (2020). How can we inspire nations of learners? An investigation of growth mindset and challenge-seeking in two countries. American Psychologist, Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000647

Renko, M., Kroeck, K. G., & Bullough, A. (2012). Expectancy theory and nascent entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 39(3), 667–684.

Revelle, W. (2018). Psych: Procedures for psychological, psychometric, and personality research. Northwestern University Retrieved from https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=psych. Accessed 15 Jun 2021.

Robichaud, Y., McGraw, E., & Roger, A. (2001). Toward the development of a measuring instrument for entrepreneurial motivation. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 6, 189–201.

Rosseel, Y. (2012). Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48, 1–36 Retrieved from http://www.jstatsoft.org/v48/i02/. Accessed 15 Jun 2021.

Ruscio, J., Haslam, N., & Ruscio, A. M. (2006). Introduction to the Taxometric method: A practical guide (1st ed.). Routledge.

Ruscio, J., & Ruscio, A. M. (2004). A nontechnical introduction to the taxometric method. Understanding Statistics, 3, 151–194. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328031us0303_2

Ruscio, J., & Wang, S. (2017). RTaxometrics: Taxometric analysis. Retrieved from https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=RTaxometrics. Accessed 15 Jun 2021.

Sakaluk, J. K. (2019). Expanding statistical frontiers in sexual science: Taxometric, invariance, and equivalence testing. The Journal of Sex Research, 56(4–5), 475–510.

Schmidt, J. A., Shumow, L., & Kackar-Cam, H. (2015). Exploring teacher effects for mindset intervention outcomes in seventh-grade science classes. Middle Grades Research Journal, 10(2), 17–32.

Shaver, K. G., Wegelin, J., & Commarmond, I. (2019). Assessing entrepreneurial mindset: Results for a new measure. Discourse and Communication for Sustainable Education, 10(2), 13–21.

Sisk, V. F., Burgoyne, A. P., Sun, J., Butler, J. L., & Macnamara, B. N. (2018). To what extent and under which circumstances are growth mind-sets important to academic achievement? Two meta-analyses. Psychological Science, 29(4), 549–571.

Smith, B. W., Dalen, J., Wiggins, K., Tooley, E., Christopher, P., & Bernard, J. (2008). The brief resilience scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 15(3), 194–200.

Sriram, R. (2014). Rethinking intelligence: The role of mindset in promoting success for academically high-risk students. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 15(4), 515–536.

Stewart Jr., W. H., & Roth, P. L. (2001). Risk propensity differences between entrepreneurs and managers: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(1), 145–153.

Thomas, F. N., Burnette, J. L., & Hoyt, C. L. (2019). Mindsets of health and healthy eating intentions. Journal of applied social psychology, 1-9.

Wang, D., Gan, L., & Wang, C. (2021). The effect of growth mindset on reasoning ability in Chinese adolescents and young adults: The moderating role of self-esteem. Current Psychology, 1–7.

Wigfield, A., & Eccles, J. (2000). Expectancy-value theory of motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25, 68–81.

Yeager, D. S., & Dweck, C. S. (2012). Mindsets that promote resilience: When students believe that personal characteristics can be developed. Educational Psychologist, 47(4), 302–314.

Zhao, H., Seibert, S. E., & Hills, G. E. (2005). The mediating role of self-efficacy in the development of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(6), 1265–1272.

Code Availability

See online OSF files.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Authors are listed in order of contribution.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

Approved by the Human Subjects Review Board at NC State University.

Consent to Participate

Was secured for each individual.

Consent for Publication

Granted.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from participants before they completed our online survey. This work was conducted in accordance with the IRB at NC State University, protocol #21000.

Conflict of Interest

No funding was received to assist in the preparation of this manuscript. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

All items used the same 1–7 scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree).

Appendix A. Measures

All items used the same 1–7 scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree).

Mindsets of Entrepreneurship

-

1.

I have a certain amount of entrepreneurial ability, and I can’t really do much to change it.

-

2.

My entrepreneurial ability is something about me that I can’t change very much.

-

3.

To be honest, I can’t really change my entrepreneurial ability.

Mindsets of Leadership

-

1.

I have a certain amount of leadership ability, and I can’t really do much to change it.

-

2.

To be honest, I can’t really change my ability to lead.

-

3.

Becoming a good leader takes time, effort, and energy.

Mindsets of Creativity

-

1.

I have a certain amount of creativity and I really can’t do much to change it.

-

2.

You either are creative or are not—even trying very hard you cannot change much.

-

3.

Some people are creative, others aren’t—and no practice can change it.

Mindsets of Intelligence

-

1.

I don’t think I personally can do much to increase my intelligence.

-

2.

To be honest, I don’t think I can really change how intelligent I am.

-

3.

With enough time and effort, I think I could significantly improve my intelligence level.

Mindsets of People

-

1.

People can do things differently, but the important parts of who they are can’t really be changed.

-

2.

The kind of person someone is is something very basic about them that can’t be changed very much.

-

3.

Everyone is a certain type of person, and there is not much that can be done to really change that.

Big Five

“ How well do the following statements describe your personality? I see myself as someone who...”

-

1.

...is reserved.

-

2.

...is generally trusting.

-

3.

...tends to be lazy.

-

4.

...is relaxed, handles stress well.

-

5.

...has few artistic interests.

-

6.

...is outgoing, sociable.

-

7.

...tends to find fault with others.

-

8.

...does a thorough job.

-

9.

...gets nervous easily.

-

10.

...has an active imagination.

-

11.

...is considerate and kind to almost everyone.

Risk Taking

“Using the scale below, please indicate the extent to which you agree or disagree with the following statements.”

-

1.

I enjoy being reckless.

-

2.

I take risks.

-

3.

I seek danger.

-

4.

I know how to get around the rules.

-

5.

I am willing to try anything once.

-

6.

I seek adventure.

-

7.

I would never go hang-gliding or bungee-jumping.

-

8.

I would never make a high-risk investment.

-

9.

I stick to the rules.

-

10.

I avoid dangerous situations.

Resilience

“Please indicate how accurately that trait describes you...”

-

1.

I tend to bounce back quickly after hard times.

-

2.

I have a hard time making it through stressful events.

-

3.

It does not take me long to recover from a stressful event.

-

4.

It is hard for me to snap back when something bad happens.

-

5.

I usually come through difficult times with little trouble.

-

6.

I tend to take a long time to get over set-backs in my life.

Need for Achievement

“To what degree do you agree with the following four statements?”

-

1.

I need to meet the challenge.

-

2.

I need to continue learning.

-

3.

I need personal growth.

-

4.

I need to prove that I can succeed.

Self-Efficacy

“I am confident that I can…”

-

1.

Identify new business opportunities

-

2.

Create new products

-

3.

Think creatively

-

4.

Commercialize an idea or new development

Value- Enjoyment/Utility

“Please indicate the extent to which you agree or disagree with the following statements.”

-

1.

Being an entrepreneur is enjoyable.

-

2.

Being an entrepreneur is interesting.

-

3.

Being an entrepreneur could help me achieve other important goals in my life.

-

4.

Being an entrepreneur provides more opportunities than other career options.

Value- Identity

“Please indicate the extent to which you agree or disagree with the following statements.”

-

1.

Being an entrepreneur is an important part of my identity.

-

2.

Being an entrepreneur is important to who I am.

Cost

“Please indicate the extent to which you agree or disagree with the following statements.”

-

1.

Being an entrepreneur demands too much time.

-

2.

Being an entrepreneur is too much work.

-

3.

I have so many other responsibilities that I am unable to put in the effort necessary to be an entrepreneur.

-

4.

Being an entrepreneur is too stressful.

Appendix B. Data Analysis

Goal 1

Research Question 1: Taxometric Analysis

Taxometrics is a quantitative analysis that assesses whether a set of observed scores reflects an underlying categorical latent variable or an underlying continuous latent variable (Borsboom et al., 2016; Meehl, 1992; Ruscio et al., 2006; Ruscio & Ruscio, 2004). It answers the question of whether observed scores are likely the product of latent discrete classes or profiles, on the one hand, versus continuous latent factors or dimensions, on the other. This conclusion, in turn, offers researchers guidance on the empirical techniques best suited for subsequent empirical investigation—that is, should researchers undertake latent class analysis (for categorical structures), or factor analysis (for continuous structures).

Taxometric analysis works by determining the fit of both latent categorical and latent continuous models to the observed data, then formally comparing these degrees of fit. This approach provides a quantitative index of how much better (or worse) a continuous measurement model captures the data, relative to a discrete measurement model. Specifically, and as implemented in the R package used here (RTaxometrics; Ruscio & Wang, 2017), the software simulates data assuming an ideal latent categorical structure, then simulates data assuming an ideal latent continuous structure, and then compares the fit of the observed data to each of the two simulated datasets. Fit of the observed data to each simulated dataset is measured using a variant of the Root Mean Squared Residual (RMSR). These two fit measures are then combined into a single index of relative fit, referred to as the Comparative Curve Fit Index (CCFI). The CCFI ranges from 0 to 1, with values substantially greater than .50 (.55 or higher) representing support for a latent categorical model, values substantially less than .50 (.45 or lower) representing support for a latent continuous model, and values near .50 indicating unclear results (Sakaluk, 2019). In practice, the above procedure is performed using three different specifications of “ideal” categorical and continuous latent structure (for details, see Ruscio & Wang, 2017), with a CCFI value generated for each approach (termed “MAMBAC,” “MAXEIG,” and “L-Mode,”, respectively), as well as an overall CCFI that averages all three outputs. In this way, researchers can determine whether multiple approaches converge on the same conclusion—either categorical or continuous latent structure (Ruscio et al., 2006).

In accordance with conventional recommendations (Ruscio & Wang, 2017), data were first checked to gauge their suitability for taxometric analysis (for data analytics overview). Data checks indicated no issues with skew or with item validities (discriminatory ability). Although some within-group correlations were above recommended levels for taxometrics, we proceeded with analyses.

For the present investigation, we entered composite scores for each of the five mindset scales—Entrepreneurship, Leadership, Creativity, Intelligence, and Personality—as continuous indicators into the taxometric analysis. In accord with the suggestions of Sakaluk (2019), a researcher-provided initial estimate of the taxonic base rate (a parameter necessary to simulate data under the assumption of idealized categorical structure) was used—in this case .25. This initial estimate allows CCFI values to be generated efficiently, during which process the software generates an empirically estimated taxonic base rate. The analysis was then re-run using the empirical estimate of the base rate.

Research Question 2: Factor Analysis

To determine the number of dimensions underlying growth mindsets of entrepreneurship, we conducted both exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. In order to improve generalizability of results, we randomly split the data into training and test datasets (N = 297 in each case), conducting exploratory factor analysis with the training data, and confirmatory factor analysis with the test data.

Exploratory factor analysis was conducted using the R package psych (Revelle, 2018). Number of factors was determined using a variety of criteria, including parallel analysis, root mean square residuals, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and interpretability of resulting factor loadings, in addition to Kaiser’s criterion and the scree plot. When multi-factor solutions were estimated, oblimin rotation was used, on the assumption that resulting factors were likely to correlate.

Confirmatory factor analysis was conducted using the R package lavaan (Rosseel, 2012). Model fit was assessed with the Chi-squared test, Comparative Fit Index (CFI), RMSEA, and Standardized Root Mean Residual (SRMR). Robust versions of these criteria were employed when deviations from multivariate normality were indicated.

Exploratory Factor Analysis

Exploratory factor analysis was conducted on the training dataset. Given that each of the five mindset scales was had been previously validated, we entered composite scores for each scale (Flora, 2018). The strongest correlations occurred between entrepreneurship and leadership (.74) and between personality and creativity (.70). Inspection of a Normal Q-Q plot in conjunction with results of Mardia’s test suggested that the data could not be assumed multivariate normal. Accordingly, unweighted least squares estimation was used where possible.

Parallel analysis, inspection of a scree plot, and examination of eigenvalues in light of Kaiser’s criterion suggested the presence of either one or two factors (see Table 2). Therefore, we ran both a one-factor and a two-factor model for further examination. Because any two factors would likely be correlated (given than all variables represent facets of mindsets), oblimin rotation was used to interpret loadings.

Factor loadings for the one-factor model are provided in Table 3, for the two-factor model in Table 4. Additional criteria for distinguishing between the two models—beyond parallel analysis, a scree plot, and Kaiser’s criterion—were based upon Flora (2018), and included root mean square residuals (RMSR), visual inspection of the residual matrix, an exact-fit test, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and interpretation of factor loadings. Results are summarized in Table 2.

The one-factor solution accounted for 60% of variance, with all factor loadings greater than .50. RMSR was .04 and inspection of residual matrix revealed that all residuals were less than .10—both of which are consistent with good model fit. However, the exact-fit test was significant (p < .001), and the lower bound of the 90% confidence interval for RMSEA was > .10, with the latter finding in particular suggesting poor fit. A two- factor solution was estimated using unweighted least squares, but produced a Heywood case. A two-factor solution using maximum likelihood was then estimated and converged normally. Collectively, the two factors accounted for 69% of the variance, and overall exhibited notably better fit. The hypothesis of exact fit was not rejected (p = .67), RMSR was < .01, and the lower bound of the 90% confidence interval for RMSEA was 0. Interpretability, however, was not entirely clear. As Table 4 shows, mindsets of entrepreneurship and leadership clustered together—which makes theoretical sense. But the loading for entrepreneurship was suspiciously high (and indeed was out-of-bounds using other forms of rotation). More worryingly, the remaining variables—intelligence, creativity, and personality—did not uniquely and strongly specify a single factor. Specifically, mindset of leadership showed signs of cross-loading (.39 on the “personality” factor, as well as .47 on the “entrepreneurship” factor). Additionally, the two factors correlated strongly (.70), but not above the threshold of .85, which is generally considered sufficient to conclude that the latent structure is unidimensional (Brown, 2015).

Altogether, the general better statistical fit of the two-factor model led us to slightly favor a two-factor structure in which mindsets of entrepreneurship and leadership clustered together, but parsimony and interpretability kept us open to the possibility of a one-factor solution.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Confirmatory factor analysis was conducted on the test dataset. As with the EFA, composite scale scores for each mindset domain were used. Results of Mardia’s test again suggested that the data could not be assumed multivariate normal. Accordingly, models were estimated using robust maximum likelihood estimation (“MLM”).

A two-factor model was estimated, with the first factor consisting of mindsets of entrepreneurship and leadership, and the second factor consisting of mindsets of creativity, intelligence and personality. For both factors, the metric of the latent was set by the mindset scale that loaded most strongly on the factor during the exploratory stage of analysis. Thus, mindset of entrepreneurship set the metric for Factor 1, and mindset of personality set the metric for Factor 2. Model estimation terminated normally. Fit of the model was good based on multiple major indices: robust χ2 (4) = .705, p = .951; robust CFI = 1.00; robust RMSEA = 0.00; SRMR = .008. All indicators loaded strongly on their assigned factors (> .70), but the two factors exhibited an extremely high correlation of .94. This correlation was well above the recommended threshold of .85 for concluding that two factors represent a single dimension.

Accordingly, a one-factor model was estimated with mindset of entrepreneurship setting the metric of the latent. Model estimation terminated normally. Fit of the one-factor model was also good based on the same major indices: robust χ2 (5) = 3.059, p = .691; robust CFI = 1.00; robust RMSEA = 0.00, 90% CI [0.00, 0.09]; SRMR = .015. All indicators loaded strongly on the single factor (≥ .70).

The good fit of the one-factor model, together with the very high correlation of factors in the two-factor model, provided strong support for unidimensional latent structure, and additional evidence boosted this support. First, we estimated an alternative two-factor confirmatory model with a different pattern of loadings. Specifically, we assigned mindset of personality to load with the mindsets of entrepreneurship and leadership, rather than with creativity and leadership. Fit of this model was also excellent, χ2 (4) = 1.545, p = .819, indicating that the initial two-factor specification did not seem to be highlighting a particularly meaningful pattern of clustering. Second, using the test dataset, we repeated the exploratory factor analyses that we conducted earlier on the training dataset. Parallel analysis, inspection of a scree plot, and Kaiser’s criterion all suggested one rather than two factors. But most importantly, a two-factor EFA using the test data failed to yield the same pattern that was observed with the training data, in which entrepreneurship and leadership clustered together in one factor, while creativity, intelligence, and personality clustered in another. Indeed, with the test data, there was no interpretable second factor at all—factor loadings for the second factor were uniformly below .30. Thus, EFA results for a two-factor solution from the test dataset did not replicate those from the training dataset.

Goal 2

Research Questions 3 & 4: Correlation Analyses

To examine discriminant validity, we first report correlations of mindsets with each of the items in the Big Five. For convergent validity, we report correlations of mindsets with the three traits associated with successful entrepreneurship—namely, risk-taking, resilience and need for achievement.

Goal 3

Research Questions 5–8: Regression Analyses

All linear regression models were reported using unstandardized parameter estimates. These estimates were denoted with “b,” and because both predictor and outcome variables were assessed on 7-point scale, “b” indicates the expected change in outcome (on the 7-point scale) for a 1 unit increase in growth mindset. Statistical inference was made using a two-tailed alpha of .05. For moderation analyses, dummy coding was used to distinguish entrepreneurs (“1”) from non-entrepreneurs (“0”). Mediation and moderation analyses were conducted using the “Process” macro for R Version 3.5, beta 0.1 (Hayes, 2018). Prior to regression analyses, weak metric invariance of mindset items was established between entrepreneurs and non-entrepreneurs, ensuring that any significant interactions observed in the data were not due to differences in measurement properties of mindset between the two groups.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Billingsley, J., Lipsey, N.P., Burnette, J.L. et al. Growth mindsets: defining, assessing, and exploring effects on motivation for entrepreneurs and non-entrepreneurs. Curr Psychol 42, 8855–8873 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02149-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02149-w