Abstract

Purpose

The European Ecolabel (EU Flower) has the mission to encourage cleaner production and influence consumers to promote Europe’s transition to a circular economy. Nonetheless, little is known about EU Ecolabel evolution; it is not clear what the drivers that encourage its implementation are. Thus, this study aims to assess the growing acceptance of the EU Ecolabel in the European Union, and Spain more specifically, by examining product and service categories and geographical regions.

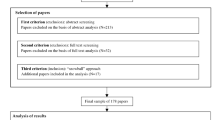

Methods

The methodological approach taken in this study is a mixed methodology based on the triangulation method by consulting the EU Ecolabel scheme database, EU Ecolabel delegates from some autonomous regions, and the academic literature. Also, a geographic analysis was run in the ArcGIS Software with data about the accumulation of licenses assigned in 2016.

Results and discussion

The analysis shows that most products in Spain that have been awarded the EU Ecolabel belong to the following categories: Do-It-Yourself Products (paint and varnish), Paper Products, Cleaning Up Products, and Electronic Equipment. At the same time, the study showed that this ecolabel faces significant obstacles in its diffusion, such as the competition with environmental labels launched previously in Europe and other regional labels.

Conclusions

The results of this study indicate the existence of five drivers that may encourage the implementation of EU Flower in a region: (1) public management, (2) communication strategy, (3) sustainable public procurement criteria, (4) local income per capita, and (5) international trade incentives.

Finally, this study provides essential recommendations for policymakers to trigger ecolabeling practices such as the need to improve the understanding of the EU ecolabel impact in different levels of activity, which means countries, regions, industrial clusters, firms, and consumers. Also, this investigation identifies areas for further research, and it expresses the need to develop business case studies about ecolabeling with the objective to visualize this phenomenon as an eco-innovation process.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Aguilar FX, Cai Z (2010) Conjoint effect of environmental labeling, disclosure of forest of origin and price on consumer preferences for wood products in the US and UK. Ecol Econ 70:308–316

Armah PW (2002) Setting eco-label standards in the fresh organic vegetable market of Northeast Arkansas. J Food Distrib Res 33:1–11

Bleda M, Valente M (2009) Graded eco-labels: a demand-oriented approach to reduce pollution. Technol Forecast Soc Change 76:512–524

Bonsi R, Hammett L, Smith B (2008) Eco-labels and international trade: problems and solutions. J World Trade 42:407–432

Brécard D, Hlaimi B, Lucas S, Perraudeau Y, Salladarré F (2009) Determinants of demand for green products: an application to eco-label demand for fish in Europe. Ecol Econ 69:115–125

Chamorro A, Bañegil TM (2006) Green marketing philosophy: a study of Spanish firms with ecolabels. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 13:11–24

Daddi T, Iraldo F, Testa F (2015) Environmental certification for organisations and products: management approaches and operational tools. Routlegde Research in Sustainability and Business

Dangelico RM, Pujari D (2010) Mainstreaming green product innovation: Why and how companies integrate environmental sustainability. J Bus Ethics 95:471–486

Dekhili S, Achabou MA (2015) The influence of the country-of-origin ecological image on ecolabelled product evaluation: an experimental approach to the case of the European ecolabel. J Bus Ethics 131:89–106

Delmas MA, Grant LE (2014) Eco-Labeling Strategies and Price-Premium. In: Eco-labeling strategies and price-premium: the wine industry puzzle

Denzin NK (1989) The research act - a theoretical introduction to sociological methods, 3rd Editio edn. Amer Sociological Assoc, Washington

DiCicco-Bloom B, Crabtree BF (2006) The qualitative research interview. Med Educ 40:314–321

Dietz T, Stern PC, National RC (2002) New tools for environmental protection : education, information, and voluntary measures. National Academies Press, Washington, DC

Dziuba R (2016) Sustainable development of tourism - EU ecolabel standards illustrated using the example of Poland. Comp Econ Res 19:111–128

Ellen MacArthur Foundation (2017) Programmes. https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/programmes. Accessed 9 Jun 2018

EU Ecolabel Helpdesk Team (2017) EU Ecolabel by Country and Product Group

European Commission (2015a) Closing the loop: an ambitious EU circular economy package

European Commission (2015b) Closing the loop—an EU action plan for the circular economy. Brussels

European Commission (2015c) Closing the loop - An EU action plan for the Circular Economy. Brussels, 2.12.2015 COM(2015) 614 final. Communication from the commission to the european parliament, the council, the european economic and social committee and the committee of the regions. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52015DC0614. Accessed 30 July 2017

European Commission (2016a) Circular economy: commission expands Ecolabel criteria to computers, furniture and footwear. Press Release

European Commission (2016b) Ecolabel—facts and figures. http://ec.europa.eu/environment/ecolabel/facts-and-figures.html. Accessed 24 Mar 2017

European Commission (2018) Product groups and criteria—Ecolabel. http://ec.europa.eu/environment/ecolabel/products-groups-and-criteria.html. Accessed 14 Jun 2018

Evans L, Nuttall C, Gandy S et al (2015) Project to support the evaluation of the implementation of the EU Ecolabel regulation. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg

Fischer C, Lyon TP (2013) A theory of multi-tier ecolabels. Ann Arbor 1001:48109

Foundation for Environmental Education (FEE) (2018) The results of the Blue Flag International Jury 2018. http://www.blueflag.global/beaches2

Fraguell RM, Martí C, Pintó J, Coenders G (2016) After over 25 years of accrediting beaches, has Blue Flag contributed to sustainable management? J Sustain Tour 24:882–903

Francis P (2015) Laudato si: on care for our common home. Vatican

Global Ecolabelling Network (2004) Introduction to ecolabelling. Glob Ecolabelling Netw Inf Pap

Gordy L (2002) Differential importance of ecolabel criteria to consumers. In: Ecolabels and the Greening of the Food Market. Conference Proceedings, pp 1–9

Greaker M (2006) Eco-labels, trade and protectionism. Environ Resour Econ 33:1–37

Hemmelskamp J, Brockmann KL (1997) Environmental labels—the German ‘Blue Angel. Futures 29:67–76

Horne RE (2009) Limits to labels: the role of eco-labels in the assessment of product sustainability and routes to sustainable consumption. Int J Consum Stud 33:175–182

i Canals LM, Domènèch X, Rieradevall J et al (2002) Use of life cycle assessment in the procedure for the establishment of environmental criteria in the Catalan eco-label of leather. Int J Life Cycle Assess 7:39–46

IEFE Bocconi, Iraldo F, Kahlenborn W, et al (2005) EVER: evaluation of EMAS and eco-label for their revision. Report 2. Milan

Iraldo F, Barberio M (2017) Drivers, barriers and benefits of the EU ecolabel in European companies’ perception. Sustain 9:1–15

ISO, ICONTEC (2002) 14020: 2002. Etiquet. ecológicas y Declar. Ambient. Gen

Jaca C, Prieto-Sandoval V, Psomas E, Ormazabal M (2018) What should consumer organizations do to drive environmental sustainability? J Clean Prod 181:201–208

Johnson D, Turner C (2006) European business. Routledge, London

Kimchi J, Polivka B, Stevenson JS (1991) Triangulation: operational definitions. Nurs Res 40:364–366

Konishi Y (2011) Efficiency properties of binary ecolabeling. Resour Energy Econ 33:798–819

Leire C, Thidell Å (2005) Product-related environmental information to guide consumer purchases—a review and analysis of research on perceptions, understanding and use among Nordic consumers. J Clean Prod 13:1061–1070

Lewandowski M (2016) Designing the business models for circular economy—towards the conceptual framework. Sustain 8:1–28

Linder M, Williander M (2017) Circular business model innovation: inherent uncertainties. Bus Strateg Environ 26:182–196

Loureiro ML, Lotade J (2005) Do fair trade and eco-labels in coffee wake up the consumer conscience? Ecol Econ 53:129–138

Loureiro ML, McCluskey JJ, Mittelhammer RC (2001) Assessing consumer preferences for organic, eco-labeled, and regular apples. J Agric Resour Econ 26:404–416

Loureiro ML, McCluskey JJ, Mittelhammer RC (2002) Will consumers pay a premium for eco-labeled apples? J Consum Aff 36:203–219

Melser D, Robertson PE (2005) Eco-labelling and the trade-environment debate, pp 49–63

Meredith J (1993) Theory building through conceptual methods. Int J Oper Prod Manag 13:3–11

Ministerio de la Presidencia (2008) ORDEN PRE/116/2008, de 21 de enero, por la que se publica el Acuerdo de Consejo de Ministros por el que se aprueva el Plan de Contratación Pública Verde de la Administración General del Estado y sus Organismos de la Seguridad Social. Spain

Ministry of Economy Industry and Competitiveness (2015) Datacomex, foreign trade statistics

Monteiro J (2010) Eco-label adoption in an interdependent world. IRENE Inst Econ Res Work Pap Ser

Myers MD, Newman M (2007) The qualitative interview in IS research: examining the craft. Inf Organ 17:2–26

Oakdene Hollins (2011) EU Ecolabel for food and feed products—feasibility study

Panainte M, Inglezakis V, Caraman I, Nicolescu MC, Mosnegu.u E, Nedeff F (2014) The evolution of eco-labeled products in Romania. Environ Eng Manag J 13:1665–1671

Parikka-Alhola K (2008) Promoting environmentally sound furniture by green public procurement. Ecol Econ 68:472–485

Prag A, Lyon T, Russillo A (2016) Multiplication of environmental labelling and information schemes (ELIS): implications for environment and trade. OECD Environ Work Pap 106. https://doi.org/10.1787/5jm0p33z27wf-enOECD

Preston F (2012) A global redesign? Shaping the circular economy. Energy Environ Resour Gov 2:1–20

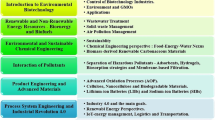

Prieto-Sandoval V, Alfaro JA, Mejía-Villa A, Ormazabal M (2016) ECO-labels as a multidimensional research topic: trends and opportunities. J Clean Prod 135:806–818

Prieto-Sandoval V, Jaca C, Ormazabal M (2018) Towards a consensus on the circular economy. J Clean Prod 179:605–615

Rametsteiner E (1999) The attitude of European consumers towards forests and forestry. UNASYLVA-FAO- 42–47

Reisch LA (2001) Eco-labeling and sustainable consumption in Europe: lessons to be learned from the introduction of a national label for organic food. ConsInterAnn 47:1–6

Rubik F, Scheer D, Iraldo F (2008) Eco-labelling and product development: Potentials and experiences. Int J Prod Dev 6:393–419.: https://doi.org/10.1504/IJPD.2008.020401

Salzhauer AL (1991) Obstacles and opportunities for a consumer ecolabel. Environment 33:10–37

Salzman J (1991) Environmental labelling in OECD countries. OECD

Saunders M, Lewis P, Thornhill A (2009) Research methods for business students, fifth edit. Pearson Education Limited, Edinburgh

Statistics National Institute of Spain (2015) Contabilidad Regional de España (Base 2010). PIB Per Cápita

Testa F, Iraldo F, Vaccari A, Ferrari E (2015) Why eco-labels can be effective marketing tools: evidence from a study on Italian consumers. Bus Strateg Environ 24:252–265

The Swedish Society for Nature Conservation (1999) Changes in household detergents: a statistical comparison between 1988 and 1996

Thøgersen J, Haugaard P, Olesen A (2010) Consumer responses to ecolabels. Eur J Mark 44:1787–1810

Thøgersen J, Jørgensen A, Sandager S (2012) Consumer decision making regarding a “green” everyday product. Psychol Mark 29:187–197

Tukker A (2015) Product services for a resource-efficient and circular economy—a review. J Clean Prod 97:76–91

United Nations (1993) Report of the United Nations conference on environment and development, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil,3–14 June 1992. United Nations, New York

United Nations (2002) Report of the world summit on sustainable development. Johanesburg

UNWTO (2016) UNWTO tourism highlights 2016. Madrid

UNWTO (2017) Tourism highlights, 2017th edn. United Nations

Villot XL, González CL, Rodríguez MXV (2007) Economía ambiental. Prentice Hall, Madrid

WCED (1987) Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: our common future acronyms and note on terminology chairman’s foreword. Oxford ; New York : Oxford University Press, 1987, Brundtland

Witjes S, Lozano R (2016) Towards a more circular economy: proposing a framework linking sustainable public procurement and sustainable business models. Resour Conserv Recycl 112:37–44

Yong R (2007) The circular economy in China. J Mater Cycles Waste Manag 9:121–129

Zanoli R, Naspetti S (2002) Consumer motivations in the purchase of organic food: a means-end approach. Br Food J 104:643–653

Acknowledgments

This research is part of the EcoPyme project, which has been sponsored by the Spanish National Program for Fostering Excellence in Scientific and Technical Research and The European Regional Development Fund: DPI2015-70832-R (MINECO/FEDER). Likewise, this investigation is part of the project “Implementation of the circular economy in the industrial sector located in the province of Sabana Centro and its surroundings” (EICEA 117 2018) which is funded by University of La Sabana, Colombia. Moreover, the authors would like to thank the EU Ecolabel Help Desk, the Spanish Ministry for the Ecological Transition, and the regional EU Ecolabel offices for their help with data collection.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible editor: Fabio Iraldo

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 18 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Prieto-Sandoval, V., Mejía-Villa, A., Ormazabal, M. et al. Challenges for ecolabeling growth: lessons from the EU Ecolabel in Spain. Int J Life Cycle Assess 25, 856–867 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11367-019-01611-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11367-019-01611-z