Abstract

Biological age (BA) closely depicts age-related changes at a cellular level. Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2D) accelerates BA when calculated using clinical biomarkers, but there is a large spread in the magnitude of individuals’ age acceleration in T2D suggesting additional factors contributing to BA. Additionally, it is unknown whether BA can be changed with treatment. We hypothesized that potential determinants of the heterogeneous BA distribution in T2D could be due to differential tissue aging as reflected at the DNA methylation (DNAm) level, or biological variables and their respective therapeutic treatments. Publicly available DNAm samples were obtained to calculate BA using the DNAm phenotypic age (DNAmPhenoAge) algorithm. DNAmPhenoAge showed age acceleration in T2D samples of whole blood, pancreatic islets, and liver, but not in adipose tissue or skeletal muscle. Analysis of genes associated with differentially methylated CpG sites found a significant correlation between eight individual CpG methylation sites and gene expression. Clinical biomarkers from participants in the NHANES 2017–2018 and ACCORD cohorts were used to calculate BA using the Klemera and Doubal (KDM) method. Cardiovascular and glycemic biomarkers associated with increased BA while intensive blood pressure and glycemic management reduced BA to CA levels, demonstrating that accelerated BA can be restored in the setting of T2D.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

López-Otín C, et al. Hallmarks of aging: an expanding universe. Cell. 2023;186(2):243–78.

Levine ME. Modeling the rate of senescence: can estimated biological age predict mortality more accurately than chronological age? J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68(6):667–74.

Nie C, et al. Distinct biological ages of organs and systems identified from a multi-omics study. Cell Rep. 2022;38(10):110459.

Bahour N, et al. Diabetes mellitus correlates with increased biological age as indicated by clinical biomarkers. Geroscience. 2022;44(1):415–27.

Levine ME, et al. An epigenetic biomarker of aging for lifespan and healthspan. Aging. 2018;10(4):573–91.

Ribel-Madsen R, et al. Genome-wide analysis of DNA methylation differences in muscle and fat from monozygotic twins discordant for type 2 diabetes. PloS One. 2012;7(12):e51302.

Volkmar M, et al. DNA methylation profiling identifies epigenetic dysregulation in pancreatic islets from type 2 diabetic patients. EMBO J. 2012;31(6):1405–26.

Barajas-Olmos F, Centeno-Cruz F, Zerrweck C, Imaz-Rosshandler I, Martínez-Hernández A, Cordova EJ, Rangel-Escareño C, Gálvez F, Castillo A, Maydón H, Campos F, Maldonado-Pintado DG, Orozco L. Altered DNA methylation in liver and adipose tissues derived from individuals with obesity and type 2 diabetes. BMC Med Genet. 2018;19(1):28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12881-018-0542-8.

Horvath S. DNA methylation age of human tissues and cell types. Genome Biol. 2013;14(10):3156.

Pelegí-Sisó D, et al. methylclock: a bioconductor package to estimate DNA methylation age. Bioinformatics. 2021;37(12):1759–60.

Thurner M, et al. Integration of human pancreatic islet genomic data refines regulatory mechanisms at type 2 diabetes susceptibility loci. eLife. 2018;7:e31977.

Group, T.A.S. Effects of intensive blood-pressure control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(17):1575–85.

Association, A.D. 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: standards of medical care in diabetes—2021. Diabetes Care. 2020;44(Supplement_1):S15–33.

Klemera P, Doubal S. A new approach to the concept and computation of biological age. Mech Ageing Dev. 2006;127(3):240–8.

Crimmins EM, et al. Quest for a summary measure of biological age: the health and retirement study. Geroscience. 2021;43(1):395–408.

Fermin-Martinez CA, et al. AnthropoAge, a novel approach to integrate body composition into the estimation of biological age. Aging Cell. 2023;22(1):e13756.

Gao X, et al. Accelerated biological aging and risk of depression and anxiety: evidence from 424,299 UK Biobank participants. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):2277.

Kennedy BK, et al. Geroscience: linking aging to chronic disease. Cell. 2014;159(4):709–13.

Ryan J, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of environmental, lifestyle, and health factors associated with DNA methylation age. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2020;75(3):481–94.

Ashcroft FM, et al. Is type 2 diabetes a glycogen storage disease of pancreatic β cells? Cell Metab. 2017;26(1):17–23.

Mota M, et al. Molecular mechanisms of lipotoxicity and glucotoxicity in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Metabolism. 2016;65(8):1049–61.

Aguayo-Mazzucato C, et al. Acceleration of β cell aging determines diabetes and senolysis improves disease outcomes. Cell Metab. 2019;30(1):129–142.e4.

Thierry-Mieg D, Thierry-Mieg J. AceView: a comprehensive cDNA-supported gene and transcripts annotation. Genome Biol. 2006;7(Suppl 1):S12.

Martínez-Alberquilla I, et al. Neutrophils and neutrophil extracellular trap components: Emerging biomarkers and therapeutic targets for age-related eye diseases. Ageing Res Rev. 2022;74:101553.

Elkhidir AE, Eltaher HB, Mohamed AO. Association of lipocalin-2 level, glycemic status and obesity in type 2 diabetes mellitus. BMC Res Notes. 2017;10(1):285. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-017-2604-y.

Cooper-Dehoff RM, et al. Is a diabetes mellitus–linked amino acid signature associated with β-blocker–induced impaired fasting glucose? Circulation: Cardiovascular. Genetics. 2014;7(2):199–205.

Ottosson-Laakso E, et al. Glucose-induced changes in gene expression in human pancreatic islets: causes or consequences of chronic hyperglycemia. Diabetes. 2017;66(12):3013–28.

Peters I, et al. Adiposity and age are statistically related to enhanced RASSF1A tumor suppressor gene promoter methylation in normal autopsy kidney tissue. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16(12):2526–32.

Sansal I, et al. NPDC-1, a regulator of neural cell proliferation and differentiation, interacts with E2F-1, reduces its binding to DNA and modulates its transcriptional activity. Oncogene. 2000;19(43):5000–9.

Flannick J, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in SLC30A8 protect against type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2014;46(4):357–63.

Dwivedi OP, et al. Loss of ZnT8 function protects against diabetes by enhanced insulin secretion. Nat Genet. 2019;51(11):1596–606.

Bekaert B, et al. Improved age determination of blood and teeth samples using a selected set of DNA methylation markers. Epigenetics. 2015;10(10):922–30.

Hirata T, Arai Y, Yuasa S, Abe Y, Takayama M, Sasaki T, Kunitomi A, Inagaki H, Endo M, Morinaga J, Yoshimura K, Adachi T, Oike Y, Takebayashi T, Okano H, Hirose N. Associations of cardiovascular biomarkers and plasma albumin with exceptional survival to the highest ages. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):3820. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-17636-0.

Kozakova M, Palombo C. Vascular ageing and aerobic exercise. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(20):10666.

Guadagni V, et al. Aerobic exercise improves cognition and cerebrovascular regulation in older adults. Neurology. 2020;94(21):e2245–57.

Hägg S, Jylhävä J. Sex differences in biological aging with a focus on human studies. eLife. 2021;10:e63425.

Avilés-Santa ML, et al. Differences in hemoglobin A1c between Hispanics/Latinos and non-Hispanic Whites: an analysis of the hispanic community health study/study of Latinos and the 2007–2012 national health and nutrition examination survey. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(6):1010–7.

Lago RM, Singh PP, Nesto RW. Congestive heart failure and cardiovascular death in patients with prediabetes and type 2 diabetes given thiazolidinediones: a meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials. The Lancet. 2007;370(9593):1129–36.

Nissen SE, Wolski K. Effect of rosiglitazone on the risk of myocardial infarction and death from cardiovascular causes. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(24):2457–71.

Rutten FH. β-blockers and their mortality benefits: underprescribed in heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Future Cardiol. 2011;7(1):43–53.

ElSayed NA, et al. 9. Pharmacologic approaches to glycemic treatment: standards of care in diabetes-2023. Diabetes Care. 2023;46(Suppl 1):S140–s157.

Funding

This study was supported by the Institutional Startup Funds to CAM. (Joslin Diabetes Center) and NIH grants P30 DK036836 Joslin Diabetes Research Center (Bioinformatic Core) and 1R01DK132535 to CAM. ALG is a Wellcome Senior Research Fellow in Basic Biomedical Science. This work was funded at Stanford by the Wellcome (095101, 200837 [ALG]). This work was partially supported by grant 1 UG3CA268202 from NIH NCI (SenNet Consortium) to NN.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

ESM 1

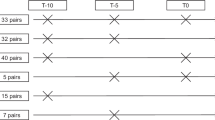

Supplemental Figure 1: Inclusion flowchart showing those ACCORD participants included in our analysis, given availability of biomarkers required for calculation of BA using KDM. (PNG 116 kb) (PDF 70 kb)

ESM 2

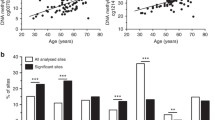

Supplemental Figure 2: In individuals with obesity, there is no difference in DNAm PhenoAge between nondiabetic and T2D in whole blood (A) and subcutaneous adipose tissue (B). Nonparametric t-test was performed. Standard error of mean (SEM) is shown. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, *** p<0.001. Relates to Fig. 1 in text. (PNG 116 kb)

ESM 3

Supplemental Figure 3: Methylation age (mAge) was determined using publicly available DNAm from nondiabetic and T2D tissues using Horvath’s mAge clock. Increased mAge was observed in whole blood (A). No significant changes were observed in pancreatic islets (B), and liver (C), skeletal muscle (D), subcutaneous (E), or visceral (F) adipose tissue. Nonparametric t-test was performed. Standard error of mean (SEM) is shown. (PNG 354 kb)

ESM 4

(DOCX 20.4 kb)

About this article

Cite this article

Cortez, B.N., Pan, H., Hinthorn, S. et al. Heterogeneity of increased biological age in type 2 diabetes correlates with differential tissue DNA methylation, biological variables, and pharmacological treatments. GeroScience 46, 2441–2461 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-023-01009-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-023-01009-8