Abstract

A growing number of researchers study the laws that regulate the third sector and caution the legal expansion is a global crackdown on civil society. This article asks two questions of a thoroughly researched form of legal repression: restrictions on foreign aid to CSOs. First, do institutional differences affect the adoption of these laws? Second, do laws that appear different in content also have different causes? A two-stage analysis addresses these questions using data from 138 countries from 1993 to 2012. The first analysis studies the ratification of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and constitution-level differences regarding international treaties’ status. The study then uses competing risk models to assess whether the factors that predict adoption vary across law types. The study finds that given ICCPR ratification, constitutions that privilege treaties above ordinary legislation create an institutional context that makes adoption less likely. Competing risk models suggest different laws have different risk factors, which implies these laws are more conceptually distinct than equivalent. Incorporating these findings in future work will strengthen the theory, methods, and concepts used to understand the legal approaches that regulate civil society.

Sources: Appe and Marchesini da Costa (2017), Carothers and Brechenmacher (2014), Chikoto-Schultz and Uzochukwu (2016); Christensen and Weinstein (2013); Cunningham (2018); Dupuy and Prakash (2017); Dupuy et al. (2016); Gershman and Allen (2006); Gugerty (2017); Hodenfield and Pegus (2013); Kameri-Mbote (2002); Maru (2017); Mayhew (2005); Rutzen (2015); Salamon and Toepler (1997); Sidel (2017); Tiwana and Belay (2010); Wolff and Poppe (2015); World Bank (1997)

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Belize and Vietnam are not analyzed because they are not coded in several datasets. These countries adopted laws in 2003 and 2009, respectively.

The ICCPR protects freedoms of expression and belief (Articles 18, 19, 27), rights to associate and organize (Articles 1, 18, 21, 22), rule of law and human rights (Articles 6, 7, 9, 14, 15, 16, 17, 25, 26), and personal autonomy and economic rights (Articles 1, 3, 8, 12, 22, 23, 25).

Costa Rica was the first to ratify (November 29, 1968), and Fiji was the 172nd and most recent (August 16, 2018).

Policy differences have theoretical implications for Kingdon’s politics and policies streams of the Multiple Stream Approach (Kingdon 1984) where various policies compete in the policy stream, and only proposals that successfully match the national mood, and the politics of policymaking get considered during the policy window (Zahariadis 2014). Through the theoretical lens of Punctuated Equilibrium Theory (Baumgartner and Jones 1991, 1993), strong, established interests in the policy subsystem make adoption of substantial policy changes less likely. Only in disequilibrium are entrenched players unable to railroad massive policy changes. In the Advocacy Coalitions Framework (Sabatier 1988; Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith 1993; Sabatier and Weible 2007), policies that are an affront to a coalition’s belief systems are met with stiff resistance, whereas minor changes may be the result of a cross-coalitional learning or the negotiated outcome of the dialogue with policymakers. While the above theories predict differences in policies affect policymaking, policy differences are shown to have different effects on public and elite opinion and the social construction of target groups (Ingram and Schneider 1990, 1991; Schneider et al. 2014) and affect the extent to which targeted groups participate in politics (MacLean 2011; Mettler and Soss 2004; Pierson 1993).

Statistical software corrections—such as relogit or firthlogit in Stata 15—for analyzing rare events with logistic regressions are not yet available for panel data or analyze requiring clustered standard errors.

This involves first collecting all the “events” and an equal number of randomly selected “non-events,” and continuing to add randomly sampled non-events and stop when the confidence intervals are sufficiently small for the substantive purposes at hand. In the rare events analysis, countries that adopt laws appear in all analyses (482 country-year observations).

Belarus (2001, 2003); Indonesia (2004, 2008); and Uzbekistan (2003, 2004).

The variable takes the value of 1 if at least one of the following nine provisions exists: “certain organizations are prohibited from receiving foreign funding”; “certain types of organizations are prohibited from receiving foreign funding”; “foreign-funded organizations prohibited from carrying out particular activities”; “foreign funding can be used only for certain purposes”; “foreign funding prohibited”; “foreign funding prohibited for certain activities”; “foreign-funded NGOs prohibited from working on certain issue areas”; “foreign-funded organizations prohibited from carrying out particular activities”; and “use of foreign funding prohibited for particular activities.”

The variable equals 1 if at least one of the following twelve provisions exists: “government approval for foreign funding”; “government approval required for particular uses of foreign”; “government may cap the amount”; “government monitoring of NGO contracts financed with foreign funding”; “government restrictions on use and source”; “government restrictions on whether foreign funding can be received”; “other restrictions on use of foreign funding”; “requirements for how organizations can receive foreign funding”; “restrictions on certain types of organizations receiving foreign funding”; “restrictions on receipt and use of foreign funding”; “restrictions on sources from which foreign funding can be acquired”; and “restrictions on use of foreign funding.”

The variable equals 1 if at least one of the following six provisions exists: “foreign funds are taxed”; “government notification of foreign funding required”; “organizations must report source of revenues”; “reporting and accounting requirements”; “reporting and accounting requirements for foreign funding”; and “reporting requirements.”

Operationally, the additive index increases by 1 for each of the following binary variables present in the constitutional system as identified by CCP: (1) power to initiate legislation (coded 1 if head of state, head of government, or government can initiate legislation); (2) power to issue decrees (coded 1 if head of state or head of government can issue decrees); (3) power to declare emergencies (coded 1 if head of state, head of government, or government can declare emergencies); (4) power to propose amendments (coded 1 if head of state, head of government, or government can propose amendments to the constitution); (5) power veto legislation (coded 0 if no vetoes are possible or can be overridden by a plurality or majority in the legislature; coded 1 if vetoes are possible but require at least 3/5 supermajority of the legislature to override veto); (6) power to challenge the constitutionality of legislation (coded 1 if head of state, head of government, or government can challenge the constitutionality of legislation); (vii) power to dissolve the legislature (coded 1 if head of state, head of government, or government can dissolve the legislature).

The logit models used here produce coefficients that represent the direction of the variable’s effect on the probability of adoption but are difficult to interpret or odds ratios whose substantive meanings depends on the specific value of the odds before they change (Long and Freese 2014: 228–235).

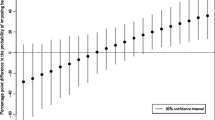

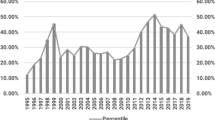

According to the Cox model with time-varying coefficients (Table 8), the level of democracy has a negative sign for all types of laws but is statistically significant for highly-restrictive laws only (− 3.05, p < 0.05). A standard deviation increase in the level of democracy (approximately 2.85 points on a 10-point scale) at the beginning of the observation period, while all other variables are held constant, yields a hazard ratio equal to exp(− 3.05*2.85) = 0.0001. Thus, the rate of adoption decreases by (100% − 0.01%) = 99.99% with a standard deviation increase in democracy at the beginning of the observation period. The time-varying component of the level of democracy has a positive sign for all types of laws but is statistically significant for highly-restrictive laws only (0.18, p < 0.05). This suggests the level of democracy as a deterrent for adopting highly-restrictive declines with every unit of time. A standard deviation increase in the level of democracy at year 10 of the observation period, while all other variables are held constant, yields a hazard ratio equal to exp(− 3.05*2.85 + 0.18*2.85*10) = 0.0283. Thus, the rate of adoption decreases by (100%-2.89%) = 97.11%. While holding all other variables constant, this discrete change at year 20 yields a hazard ratio equal to exp(− 3.05*2.85 + 0.18*2.85*20) = 4.79, which increases the rate of adoption by (479% − 100%) = 379%. Holding all else equal, a positive and discrete change in democracy causes a decrease in the rate of adoption by 99.99% at the beginning of the observation period, 97% in year 10, and increases the rate of adoption by over 350% in year 20.

According to the Cox model with time-varying coefficients (Table 8), voting alignment with Russia has a positive and statistically significant relationship with highly-restrictive laws (0.22, p < 0.01). A standard deviation increase in the voting alignment with Russia (approximately 11.75 points on a 100-point scale) at the beginning of the observation period, while all other variables are held constant, yields a hazard ratio equal to exp(0.22*11.75) = 13.26. Thus, the rate of adoption increases by 1226% with a standard deviation increase in voting alignment with Russia at the beginning of the observation period. The time-varying component has a negative and statistically significant relationship for highly-restrictive laws only (0.18, p < 0.05). This suggests the voting alignment with Russia is a propellant for adoption for highly-restrictive laws declines with every unit of time. A standard deviation in the factor, while all other variables are held constant, yields a hazard ratio equal to exp(0.22*11.75 + − 0.02*11.75*10) = 1.264. Thus, the rate of adoption increases by 26.4%. While holding all other variables constant, this discrete change at year 20 yields a hazard ratio equal to exp(0.22*11.75 + − 0.02*11.75*20) = 0.1206, which decreases the rate of adoption by (100% − 12.06%) = 87.93%. Holding all else equal, a positive and discrete change in voting alignment with Russia increases the rate of adoption by more than 1000% at the beginning of the observation period, 26% at year 10, and decreases the rate of adoption by 88% at year 20.

The dictators’ dilemma of comparative politics stresses undemocratic leaders to use their tools of office—such as elections, laws, and policy implementation—to gather information that prolongs their stay in power and maximizes their gains from office.

References

African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR) 1981 Organization of African Unity.

Aligica, P. D. (2018). Public entrepreneurship, citizenship, and self-governance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Allison, P. D. (2014). Event history and survival analysis (2nd ed.). Los Angeles: SAGE.

American Convention on Human Rights “Pact of San Jose, Costa Rica” (B-32) (ACHR) 1969 Organization of American States.

Amnesty International. (2019). Laws designed to silence: The global crackdown on civil society organizations. Online.

Amrhein, V., Greenland, S., & McShane, B. (2019a). Scientists rise up against statistical significance. Nature,567, 305–307.

Amrhein, V., Trafimow, D., & Greenland, S. (2019b). Inferential statistics as descriptive statistics: There is no replication crisis if we don’t expect replication. The American Statistician,73(sup1), 262–270.

Anheier, H. K., & Salamon, L. M. (1998). The nonprofit sector in the developing world: A comparative analysis. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Anheier, H. K., & Toepler, S. (2019). Civil society and the G20: Towards a review fo regulatory models and approaches. Retrieved from https://t20japan.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/t20-japan-tf6-10-civil-society-g20.pdf.

Arhin, A. A., Kumi, E., & Adam, M.-A. S. (2018). Facing the bullet? Non-governmental organisations (NGOs’) responses to the changing aid landscape in Ghana. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations,29(2), 348–360.

Bailey, M. A., Strezhnev, A., & Voeten, E. (2017). Estimating dynamic state preferences from United Nations voting data. Journal of Conflict Resolution,61(2), 430–456.

Baldwin, E., Carley, S., & Nicholson-Crotty, S. (2019). Why do countries emulate each others’ policies? A global study of renewable energy policy diffusion. World Development,120, 29–45.

Barber, P., & Farwell, M. M. (2017). The Relationships between State and Nonstate Interventions in Charitable Solicitation Law in the United States. In O. B. Breen, A. Dunn, & M. Sidel (Eds.), Regulatory waves: Comparative perspectives on state regulation and self-regulation policies in the nonprofit sector (pp. 199–220). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bauerle Danzman, S., Winecoff, W. K., & Oatley, T. (2017). All crises are global: Capital cycles in an imbalanced international political economy. International Studies Quarterly,61(4), 907–923.

Baumgartner, F. R., & Jones, B. D. (1991). Agenda dynamics and policy subsystems. The Journal of Politics,53(04), 1044–1074.

Baumgartner, F. R., & Jones, B. D. (1993). Agendas and instability in American politics. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Benevolenski, V. B., & Toepler, S. (2017). Modernising social service delivery in Russia: Evolving government support for non-profit organisations. Development in Practice,27(1), 64–76.

Bloodgood, E. A., Tremblay-Boire, J., & Prakash, A. (2014). National styles of NGO regulation. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly,43(4), 716–736.

Boettke, P. J., & Candela, R. A. (2019). Productive specialization, peaceful cooperation and the problem of the predatory state: Lessons from comparative historical political economy. Public Choice. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-019-00657-9.

Box-Steffensmeier, J. M., & Jones, B. S. (2004). Event history modeling: A guide for social scientists. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Brass, J. N. (2012). Why do NGOs go where they go? Evidence from Kenya. World Development,40(2), 387–401.

Brass, J. N. (2016). Allies or adversaries? NGOs and the state in Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Brass, J. N., Longhofer, W., Robinson, R. S., & Schnable, A. (2018). NGOs and international development: A review of thirty-five years of scholarship. World Development,112, 136–149.

Breen, O. B., Dunn, A., & Sidel, M. (Eds.). (2017). Regulatory waves: Comparative perspectives on state regulation and self-regulation policies in the nonprofit sector. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Breen, O. B., Dunn, A., & Sidel, M. (2019). Riding the regulatory wave: Reflections on recent explorations of the statutory and nonstatutory nonprofit regulatory cycles in 16 jurisdictions. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 48(4), 691–715.

Brennan, G., & Buchanan, J. M. (1985). The reason of rules: Constitutional political economy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Breslin, B. (2009). From words to worlds: Exploring constitutional functionality. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Brown, D. S., Brown, J. C., & Desposato, S. W. (2008). Who gives, who receives, and who wins? Transforming capital into political change through nongovernmental organizations. Comparative Political Studies,41(1), 24–47.

Buchanan, J. M. (1975). The Limits of Liberty: Between Anarchy and Leviathan. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Buchanan, J. M., & Tullock, G. (1961). The calculus of consent. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Cameron, A. C., & Trivedi, P. K. (2005). Microeconometrics: Methods and applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cammett, M. C., & MacLean, L. M. (2014). Introduction. In L. M. MacLean & M. C. Cammett (Eds.), The politics of non-state social welfare (pp. 1–16). Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Carothers, T. (2006). The backlash against democracy promotion. Foreign Affairs,85(2), 55–68.

Carothers, T. (2015). The closing space challenge: How are funders responding? Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Carothers, T., & Brechenmacher, S. (2014). Closing space: Democracy and human rights support under fire. Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Chahim, D., & Prakash, A. (2013). NGOization, foreign funding, and the Nicaraguan civil society. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations,25(2), 487–513.

Chapman, T. L. (2009). Audience beliefs and international organization legitimacy. International Organization,63(4), 733–764.

Christensen, D., & Weinstein, J. M. (2013). Defunding dissent: Restrictions on aid to NGOs. Journal of Democracy,24(2), 77–91.

CIVICUS. (2018). CIVICUS monitor. Washington, DC: World Alliance for Citizen Participation.

Cole, D. H. (2017). Laws, norms, and the institutional analysis and development framework. Journal of Institutional Economics,13(4), 829–847.

Cole, D. H., Epstein, G., & McGinnis, M. D. (2014). Toward a new institutional analysis of social-ecological system (NIASES): Combining Elinor Ostrom’s IAD and SES frameworks. Indiana Legal Studies Research Paper No. 299, August 2015.

Coppedge, M., Gerring, J., Knutsen, C. H., Lindberg, S. I., Skaaning, S.-E., Teorell, J., Altman, D., Bernhard, M., Fish, M. S., Cornell, A., Dahlum, S., Gjerløw, H., Glynn, A., Hicken, A., Krusell, J., Lührmann, A., Marquardt, K. L., McMann, K., Mechkova, V., Medzihorsky, J., Olin, M., Paxton, P., Pemstein, D., Pernes, J., von Römer, J., Seim, B., Sigman, R., Staton, J., Stepanova, N., Sundström, A., Tzelgov, E., Wang, Y.-t., Wig, T., Wilson, S., & Ziblatt, D. (2018). V-Dem [Country-Year/Country-Date] Dataset v8.

Cox, D. R. (1972). Regression models and life tables. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society,34, 187–220.

Cox, D. R. (1975). Partial likelihood. Biometrika,62(2), 269–276.

Crack, A. M. (2018). The regulation of international NGOS: Assessing the effectiveness of the INGO accountability charter. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations,29(2), 419–429.

de Tocqueville, A. (1840). Democracy in America (English ed.). Indianapolis: Liberty Fund.

DeMattee, A. J. (2019). Toward a coherent framework: A typology and conceptualization of CSO regulatory regimes. Nonprofit Policy Forum,9(4), 1–17.

Donnelly, J. (2013). Universal human rights in theory and practice (3rd ed.). Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Dupuy, K., Ron, J., & Prakash, A. (2016). Hands off my regime! governments’ restrictions on foreign aid to non-governmental organizations in poor and middle-income countries. World Development,84, 299–311.

Edwards, M. (2004). Civil society. Malden, MA: Polity Press.

Elkins, Z., Ginsburg, T., & Melton, J. (2009). The endurance of national constitutions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Elkins, Z., Ginsburg, T., & Melton, J. (2012). Constitutional constraints on executive lawmaking. Retrieved from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/summary?doi=10.1.1.434.9346.

Elkins, Z., Ginsburg, T., & Melton, J. (2014). Comparative constitutions project: Characteristics of national constitutions, Version 2.0 (2014).The Comparative Constitutions Project (CCP).

European Convention on Human Rights as amended by Protocols Nos. 11 and 14, and supplemented by Protocols Nos. 1, 4, 6, 7, 12, 13, and 16 2010 Council of Europe.

Frantz, T. R. (1987). The role of NGOs in the strengthening of civil society. World Development,15(Supplement), 121–127.

Fukuyama, F. (1995). Trust: The social virtues and the creation of prosperity. New York: Free Press.

Gibelman, M., & Gelman, S. R. (2004). A loss of credibility: Patterns of wrongdoing among nongovernmental organizations. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations,15(4), 355–381.

Gibney, M., Cornett, L., Wood, R., Haschke, P., Arnon, D., & Pisanò, A. (2017). The Political Terror Scale 1976–2016. (Political Terror Scale website: http://www.politicalterrorscale.org/.) Created online: http://www.politicalterrorscale.org/.

Gormley, W. T. (1986). Regulatory issue networks in a federal system. Polity,18(4), 595–620.

Greenland, S. (2017). Invited commentary: The need for cognitive science in methodology. American Journal of Epidemiology,186(6), 639–645.

Hadenius, A. & Teorell, J. (2005). Assessing Alternative Indices of Democracy. C&M Working Papers, IPSA.

Hanmer, M. J., & Ozan Kalkan, K. (2013). Behind the curve: Clarifying the best approach to calculating predicted probabilities and marginal effects from limited dependent variable models. American Journal of Political Science,57(1), 263–277.

Hathaway, O. A. (2002). Do human rights treaties make a difference? Faculty Scholarship Series at Yale Law School (Paper 839) (pp. 1935–2042).

Hellwig, T., & Samuels, D. (2008). Electoral accountability and the variety of democratic regimes. British Journal of Political Science,38(1), 65–90.

Henkin, L. (2000). Human rights: Ideology and aspiration, reality and prospect. In S. Power & G. T. Allison (Eds.), Realizing human rights: Moving from inspiration to impact (1st ed., pp. 3–38). New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Hyde, S. D., & Marinov, N. (2012). Which elections can be lost? Political Analysis,20(2), 191–210.

ICNL. (2009). Global philanthropy in a time of crisis. In Global trends in NGO law: A quarterly review of NGO legal trends around the world (Vol. 1, no. (2), pp. 1–10). www.icnl.org.

ICNL. (2015). The right to freedom of expression: Restrictions on a foundational right. In Global trends in NGO law: A quarterly review of NGO legal trends around the world (Vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 1–28). www.icnl.org.

Ingram, H., & Schneider, A. (1990). Improving implementation through framing smarter statutes. Journal of Public Policy,10(01), 67–88.

Ingram, H., & Schneider, A. (1991). The Choice of Target Populations. Administration & Society,23(3), 333–356.

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) 1966 United Nations General Assembly.

Jones, B. S. (1994). A longitudinal perspective on congressional elections. Ph.D. dissertation, State University of New York at Stony Brook.

Kajese, K. (1987). An agenda of future tasks for international and indigenous NGOs: Views from the south. World Development,15(Supplement), 79–85.

Kameri-Mbote, P. (2002). The operational environment and constraints for NGOs in Kenya: Strategies for good policy and practice. Switzerland: International Environmental Law Research Centre. in Geneva.

Keck, M. E., & Sikkink, K. (1999). Transnational advocacy networks in international and regional politics. International Social Science Journal,15(159), 89–101.

Kiai, M. (2012). Report of the special rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and association. United Nations General Assembly.

Kiai, M., Stern, C., Simons, D., Anderson, G., & Kaguongo, W. (2017). Full text the Freedom of Association Chapter of FOAA Online!—The world’s most user-friendly collection of legal arguments on assembly and association rights. United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights.

King, G., & Zeng, L. (2001). Logistic regression in rare events data. Political Analysis,9(2), 137–163.

Kingdon, J. W. (1984). Agendas, alternatives, and public policies. Boston, MA: Little, Brown.

Lindblom, C. E. (1959). The science of ‘muddling through’. Public Administration Review,19(2), 79–88.

Linzer, D. A., & Staton, J. K. (2015). A global measure of judicial independence, 1948–2012. Journal of Law and Courts,3(2), 223–256.

Long, J. S. (1997). Regression models for categorical and limited dependent variables. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Long, J. S., & Freese, J. (2014). Regression models for categorical dependent variables using stata (3rd ed.). College Station, TX: Stata Press Publication, StataCorp LLP.

Lowi, T. J. (1964). American business, public policy, case-studies, and political theory. World Politics,16(4), 677–715.

Lowi, T. J. (1972). Four systems of policy, politics, and choice. Public Administration Review,32(4), 298–310.

MacLean, L. M. (2011). State retrenchment and the exercise of citizenship in Africa. Comparative Political Studies,44(9), 1238–1266.

Mahajan, V., & Peterson, R. A. (1985). Models for innovation diffusion. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications.

Malesky, E., & Schuler, P. (2011). The single-party dictator’s dilemma: Information in elections without opposition. Legislative Studies Quarterly,36(4), 491–530.

Marshall, M. G., Gurr, T. R., & Jaggers, K. (2017). Polity IV Project: Political regime characteristics and transitions, 1800–2016. (Center for Systemic Peace). www.systemicpeace.org.

Maru, M. T. (2017). Legal frameworks governing non-governmental organizations in the horn of Africa. Kampala,

Mayhew, S. H. (2005). Hegemony, politics and ideology: The role of legislation in NGO–government relations in Asia. The Journal of Development Studies,41(5), 727–758.

McGinnis, M. D., & Ostrom, E. (2014). Social-ecological system framework: Initial changes and continuing challenges. Ecology and Society,19(2), 30–42.

Mettler, S., & Soss, J. (2004). The consequences of public policy for democratic citizenship: Bridging policy studies and mass politics. Perspectives on Politics,2(01), 55–73.

Morgan, P. (2018). Ideology and relationality: Chinese aid in Africa revisited. Asian Perspective,42(2), 207–238.

Murphy, W. F. (1993). Constitutions, constitutionalism, and democracy. In D. Greenberg, S. N. Katz, M. B. Oliviero, & S. C. Wheatley (Eds.), Constitutionalism and democracy: Transitions in the contemporary world (pp. 3–25). New York: Oxford University Press.

Musila, G. M. (2019). Freedoms under threat: The spread of anti-NGO measures in Africa. Retrieved from www.freedomhouse.org.

Mutunga, W. (1999). Constitution-making from the middle: Civil society and transition politics in Kenya, 1992–1997. Nairobi: SAREAT.

Ndegwa, S. N. (1996). The two faces of civil society: NGOs and politics in Africa. West Hartford, CT: Kumarian Press.

North, D. C., & Weingast, B. R. (1989). Constitutions and commitment: The evolution of institutions governing public choice in seventeenth-century England. The Journal of Economic History,49(4), 803–832.

Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ostrom, V. (1997). The meaning of democracy and the vulnerabilities of democracies: A response to Tocqueville’s challenge. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Ostrom, E. (2005). Understanding institutional diversity. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Ostrom, E. (2011). background on the institutional analysis and development framework. Policy Studies Journal,39(1), 7–27.

Ostrom, E., & Cox, M. (2010). Moving beyond panaceas: A multi-tiered diagnostic approach for social-ecological analysis. Environmental Conservation,37(4), 451–463.

Ostrom, E., & Ostrom, V. (2004). The quest for meaning in public choice. American Journal of Economics and Sociology,63(1), 105–147.

Pallas, C., Anderson, Q., & Sidel, M. (2018). Defining the scope of aid reduction and its challenges for civil society organizations: Laying the foundation for new theory. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations,29(2), 256–270.

Pierson, P. (1993). When effect becomes cause: Policy feedback and political change. World Politics,45(4), 595–628.

Pierson, P. (1994). Dismantling the welfare state? Reagan, Thatcher, and the politics of retrenchment. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Pierson, P. (2000). Increasing returns, path dependence, and the study of politics. The American Political Science Review,94(2), 251–267.

Pitkin, H. F. (1987). The idea of a constitution. Journal of Legal Education,37, 167–170.

Popplewell, R. (2018). Civil society, legitimacy and political space: Why some organisations are more vulnerable to restrictions than others in violent and divided contexts. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations,29(2), 388–403.

Powell, E. J., & Staton, J. K. (2009). Domestic judicial institutions and human rights treaty violation. International Studies Quarterly,53(1), 149–174.

Putnam, R. D. (1993). Making democracy work: Civic traditions in modern Italy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Rakner, L. (2019). Democratic rollback in Africa. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. Oxford University Press. Retrieved July 30, 2019, from https://oxfordre.com/politics/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228637-e-887.

Reddy, M. (2018). Do good fences make good neighbours? Neighbourhood effects of foreign funding restrictions to NGOs. St Antony’s International Review,13(2), 109–141.

Reimann, K. D. (2006). A view from the top: International politics, norms and the worldwide growth of NGOs. International Studies Quarterly,50(1), 45–67.

Rutzen, D. (2015). Aid barriers and the rise of philanthropic protectionism. International Journal of Not-for-Profit Law,17(1), 1–42.

Sabatier, P. A. (1988). An advocacy coalition framework of policy change and the role of policy-oriented learning therein. Policy Sciences,21(2), 129–168.

Sabatier, P. A., & Jenkins-Smith, H. C. (1993). Policy change and learning: An advocacy coalition approach. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Sabatier, P. A., & Weible, C. M. (2007). The advocacy coalition framework: Innovations and clarifications. In P. A. Sabatier (Ed.), Theories of the policy process (2nd ed., pp. 189–222). Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Salamon, L. M. (Ed.). (2002). The tools of government: A guide to the new governance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Salamon, L. M., Benevolenski, V. B., & Jakobson, L. I. (2015). Penetrating the dual realities of government-nonprofit relations in Russia. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations,26(6), 2178–2214.

Salamon, L. M., & Toepler, S. (1997). The international guide to nonprofit law. New York: Wiley.

Salamon, L. M., & Toepler, S. (2000). The influence of the legal environment on the nonprofit sector. No. 17 [Lecture]. The Johns Hopkins Center for Civil Society Studies, unpublished.

Salamon, L. M., & Toepler, S. (2012). The impact of law on nonprofit development: A framework for analysis. In C. Overes & W. van Ween (Eds.), Met Recht Betrokken (pp. 276–284). Amsterdam: Kluwe.

Sartori, G. (1976). Parties and party systems: A framework for analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schnable, A. (2015). New American relief and development organizations: Voluntarizing global aid. Social Problems,62(2), 309–329.

Schneider, A., Ingram, H., & deLeon, P. (2014). Democratic policy design: Social construction of target populations. In P. A. Sabatier & C. M. Weible (Eds.), Theories of the policy process (3rd ed., pp. 105–150). New York, NY: Westview Press.

Sidel, M. (2017). State regulation and the emergence of self-regulation in the Chinese and Vietnamese nonprofit and philanthropic sectors. In O. B. Breen, A. Dunn, & M. Sidel (Eds.), Regulatory waves: Comparative perspectives on state regulation and self-regulation policies in the nonprofit sector (pp. 92–112). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Smyth, R. (2019). Winning hybrid elections: Organized opposition, incumbent regimes, and threat of popular engagement, world politics research seminar. Indiana University Department of Political Science.

Smyth, R., & Turovsky, R. (2018). Legitimising victories: Electoral authoritarian control in Russia’s gubernatorial elections. Europe-Asia Studies,70(2), 182–201.

Stremlau, C. (1987). NGO coordinating bodies in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. World Development,15(Supplement), 213–225.

Toepler, S., Pape, U., & Benevolenski, V. (2019). Subnational variations in government-nonprofit relations: A comparative analysis of regional differences within Russia. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice. https://doi.org/10.1080/13876988.2019.1584446.

U.N. Human Rights Committee. (2006). UN Doc. CCPR/C/88/D/1274/2004: Views of the Human Rights Committee under article 5, paragraph 4, of the Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (88th session). United Nations. http://hrlibrary.umn.edu/undocs/1274-2004.html.

U.N. Human Rights Committee. (2007). UN Doc. CCPR/C/90/D/1296/2004 : Views of the Human Rights Committee under article 5, paragraph 4, of the Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political rights (9th session). United Nations. http://www.un.org/en/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=CCPR/C/90/D/1296/2004.

U.N. Human Rights Committee. (2015). UN Doc. CCPR/C/115/D/2011/2010: Views of the Human Rights Committee under article 5(4) of the Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (115th session). United Nations.

Union of International Associations. Yearbook of International Organizations. (Online: https://uia.org/yearbook). Created online: https://uia.org/yearbook.

United Nations Office of Legal Affairs. (2018). Status of ratification of a core international human rights treaty or its optional protocol. (Online)

Voeten, E. (2013). Data and analyses of voting in the UN general assembly. In Reinalda, B. (Ed.), Routledge handbook of international organization. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2111149.

Wasserstein, R. L., Schirm, A. L., & Lazar, N. A. (2019). Moving to a world beyond “p < 0.05”. The American Statistician,73(sup1), 1–19.

Wintrobe, R. (1998). The political economy of dictatorship. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Woldense, J. (2018). The ruler’s game of musical chairs: Shuffling during the reign of Ethiopia’s last emperor. Social Networks,52, 154–166.

World Bank. (1997). Handbook on good practices for laws relating to non-governmental organizations. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

World Bank. (2018). World development indicators (WDI). Washington, DC. https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/dataset/world-development-indicators.

Zahariadis, N. (2014). Ambiguity and Multiple Streams. In P. A. Sabatier & C. M. Weible (Eds.), Theories of the policy process (3rd ed., pp. 25–58). New York, NY: Westview Press.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Jennifer Brass, Terrance Chapman, Sean Nicholson-Crotty, Michelle Reddy, Chrystie Swiney, Joey Carroll, Martin Delaroche, Renzo de la Riva Agüero, Laura Montenovo, the reviewers, and the journal’s editorial team for their written comments and constructive criticisms. My appreciation also extends to those who offered early input on the project at the International Society for Third-Sector Research, Brass Club, the Emory Conference on Institutions and Lawmaking, the Midwest Political Science Association, the International Spring School on Public Policy, and the Workshop on the Ostrom Workshop (WOW6).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

See Tables 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

DeMattee, A.J. Covenants, Constitutions, and Distinct Law Types: Investigating Governments’ Restrictions on CSOs Using an Institutional Approach. Voluntas 30, 1229–1255 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-019-00151-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-019-00151-2