Abstract

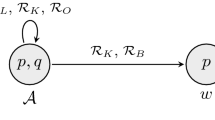

There is an important disagreement in contemporary epistemology over the possibility of non-epistemic reasons for belief. Many epistemologists argue that non-epistemic reasons cannot be good or normative reasons for holding beliefs: non-epistemic reasons might be good reasons for a subject to bring herself to hold a belief, the argument goes, but they do not offer any normative support for the belief itself. Non-epistemic reasons, as they say, are just the wrong kind of reason for belief. Other epistemologists, however, argue that there can be cases where non-epistemic reasons directly offer normative support for the beliefs a subject holds. My aim in this paper is to remove an apparent obstacle for the view that there can be non-epistemic normative reasons for belief, by showing that the existence of non-epistemic reasons for belief does not conflict with epistemic standards for the assessment of inferences. More specifically, I aim to show that the following principles are compatible. Epistemic norm of inference (ENI): necessarily, for all subjects S and inferences I: I is a good inference for S only if S can gain a (doxastically) epistemically justified belief in I’s conclusion on the basis of I’s premises. Non-epistemic reasons for belief (NERB): possibly, for some subject S, reason R, and belief B: R is a good (i.e., normative) reason for S to hold B, and R is not an epistemic reason for B. Guidance: for all subjects S, potential reasons R, and beliefs/actions φ: In order for R to count as a normative reason for S to φ, it must be possible for S to take R into account as relevant to the determination of whether S ought to φ. One might naturally think that these principles conflict, for if there are non-epistemic reasons for belief, then they must guide deliberation, and in guiding deliberation, they would violate epistemic standards. The aim of this paper is to show that no such conflict need arise. Section 2 of the paper sets out the concept of an inference, and sketches an epistemic framework for the assessment of inferences and arguments. Section 3 sets out the distinction between normative and motivating reasons, discusses motivational internalism about reasons, and briefly defends the view that there can be non-epistemic reasons for beliefs. Section 4 shows that non-epistemic reasons for belief are compatible with epistemic standards for inference and with a deliberative guidance constraint on normative reasons, because any time a reason R is a good non-epistemic reason for a subject S to hold a belief B, there is an epistemically good inference available to S which takes R as a premise and which concludes with the meta-belief that S ought to hold B. So the paper employs an indirect level-connecting principle between normative reasons for φ-ing and epistemic reasons for believing that one ought to φ. The paper ends with clarifications of that level-connecting principle, and responses to three objections.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

A bit of terminology: I use the capitalized, unitalicized “B” to name a particular mental state of belief, and belief B has the propositional content p. Below, I distinguish acts of inference and object-inferences. So, as I see it, an object-inference (OI) has premises p1, p2, … and conclusion c; a subject S has a belief B on the basis of reasons R1, R2, …; and if S performs an act of inference (AI) with content OI, then S holds a belief B with content c (i.e., S believes the conclusion of the inference) on the basis of reasons R1, R2, …, which are themselves the nonredundant premises of AI, and so R1, R2,… have content p1, p2,…. Throughout the paper, I mostly talk in terms of acts of inference and their constituent mental states, though sometimes I talk in terms of object-inferences and their propositional constituents, as appropriate.

Variations on the view that normative reasons for S to φ must be able to guide S in φ-ing and/or in deliberation about whether to φ are widely discussed. See, e.g., Markovits (2011), Parfit (2011), and Littlejohn (2012) for criticisms, and Williams (1981), Gibbons (2013), Lord (2015), Way (2017), and Bondy (2018) for defense. For the purpose of this paper, I assume without argument that Guidance is correct. I will, however, say a word about this way of formulating the Guidance principle below, in Sect. 3.3.

A referee notes that there is a widely-discussed and more pressing worry than that about the compatibility of non-epistemic reasons for belief and epistemic norms for inference: non-epistemic reasons for belief are just not the kind of thing that humans are psychologically capable of taking into account, and of holding beliefs on the basis thereof. Shouldn’t my main target here be to show that forming beliefs on the basis of non-epistemic reasons is psychologically possible?

I do argue below that it seems psychologically plausible that people sometimes take non-epistemic reasons into account in belief-formation. But arguing for this claim is only a subsidiary goal in this paper. For once we acknowledge the psychological plausibility of beliefs formed on the basis of non-epistemic reasons, we will yet want to know: how do such reasons occur in inferences? Are they compatible with standard epistemic accounts of good inference?

This is much like how Boghossian (2014) characterizes the kind of inference he’s interested in: for Boghossian, inference is what we engage in when we consider premises, and then, on the basis of our consideration of the premises, we come to hold a new or revised doxastic attitude regarding the conclusion. Boghossian’s characterization is a little bit too narrow, for there are cases where we draw inferences but our doxastic attitude with respect to the conclusion does not change (we might already have fully believed the conclusion, for example), but aside from that it is an accurate characterization of what I mean by “acts of inference”. Much of the recent work on inferences (e.g., by Boghossian (2014), Broome (2014), Neta (2013), Wright (2014), Setiya (2013), and Wedgwood (2012)) has tended to be aimed at addressing the question: what does it take for a mental event to count as an act of inference? And what makes such mental events count as good inferences?

Propositional justification is the justification one has for having a given doxastic attitude with respect to a given proposition p; doxastic justification is the justification of the doxastic attitudes one has when one believes as one epistemically ought. One might have propositional justification for a proposition one does not believe. One might also have propositional justification for a belief one holds, even if one holds the belief improperly, e.g. by basing one’s belief on bad reasons instead of the good ones one possesses, or else by basing one’s belief on the good reasons one possesses but in a bad way. Good acts of inference are those which doxastically justify belief in their conclusions.

Some epistemologists think that premises must be known in order for them to be acceptable as premises in inferences, or that premises must be both justified and true, but these are not my own view, and in any case, these views entail that the premises of good inferences must be rationally acceptable, so the worry about a possible conflict between ENI, NERB, and Guidance will arise for these views of premise adequacy too.

Or at the very least, good inferences typically transmit justification to their conclusions from their premises. One might think that cases of the sort that Sorenson (1991) discusses are counterexamples to the claim that good inferences must transmit justification (e.g., “some arguments are written in black ink, therefore some arguments are written in black ink”). Or one might be an infinitist about the structure of justification, and hold that good inference-chains can generate doxastic justification where there was none to begin with (e.g. Klein 2005, 2007a, b). But see Goldman (2003) for persuasive replies to Sorenson, and, e.g., Ginet (2005a, b) for arguments against infinitism and for foundationalism.

There are many challenges to the evidentialist view of epistemic reasons and justification, of course (see, for example, (Dougherty ed. 2011) for various objections, replies, and clarifications of evidentialist claims). Still, it is fairly uncontroversial that if S possesses R, and R is good evidence for B, then R is an epistemic reason for holding B—though Leite (2007) dissents on the grounds that real reasons have normative force, and evidence need not always have any normative force for a subject. Foley (1993, ch. 1) also claims that evidence need not constitute epistemic reason for belief, in those very exceptional cases where forming the target belief will simultaneously cause a change in the evidential circumstances.

See Hazlett (2013, chapters 2 and 3) for discussion of how such beliefs bear on a person’s mental well-being, and how they very often persist even in the face of evidence indicating that humans typically overestimate how well others like them. (Sure, people in general have an unjustified level of confidence in Well—but in my case, others do think well of me!).

See Turri et al. (2018) for experimental confirmation of the common-sense attributability of belief or refusal to believe, even in the face of a lack of evidence which would justify the subject of the attribution in holding the doxastic state in question. Turri et al. argue that this shows that beliefs held on the basis of or motivated by non-epistemic reasons are conceptually possible.

For example, see Shah (2003, 2006, 2013), Velleman (2000, ch. 11), Shah and Velleman (2005), Kelly (2002), Raz (2009), Adler (2002), Williams (1973), Wedgwood (2002), Feldman (2000). But see Stroud (2006), Reisner (2008, 2009), McCormick (2015), Leary (2017), and Bondy (2018) for defense of the view that there can be good non-epistemic reasons for belief.

The “ought to believe” in Transparency is explicitly not meant to be read in a purely epistemic sense. Rather, the question whether we ought to believe that p is meant to be read in the deliberative, all-relevant-things-considered sense. For if the “ought” in Transparency were merely a disguised epistemic ought, then it would be simply trivial that only epistemic reasons can be reasons which bear on this question, and the Transparency principle would be unable to combine with the Guidance principle to rule out the possibility of non-epistemic normative reasons for belief.

Williams (1981) famously argued in defense of a version of internalism about normative reasons. But I won’t address Williams’s version of internalism here.

I thank a referee for this journal for pressing this objection and prompting an explanation of the connection between these different internalist and Guidance principles.

Not to mention that I have defended Guidance elsewhere (Bondy 2018, Chapter 3), so I am particularly concerned with its compatibility with epistemic norms of inference.

See James (1949/1897), Ginet (2001), and McCormick (2015) for discussion of other cases of this sort. Leary (2017) considers instead cases where a combination of epistemic and non-epistemic reasons prompt belief. While Peace of Mind might be understood as a case of the sort Leary describes, I intend Peace of Mind to be an inference a subject might run even in the absence of positive evidence supporting the truth of moral realism.

In Bondy (2018), rather than Peace of Mind, I employed a more complicated argument as a counterexample to Transparency. That argument was meant to illustrate the possibility of inferentially holding a belief on the basis of non-epistemic reasons, and it strikes me as psychologically very realistic, but it makes use of an extra inferential step, and it involves a conclusion about religious belief. These extra features are distracting and unnecessary. I therefore use the much simpler Peace of Mind here, which strikes me as also psychologically plausible.

I also respond more fully to Transparency- and aim-of-belief-style arguments against the possibility of taking non-epistemic reasons into account in doxastic deliberation in my (2018). However, in the present paper, my primary goal is to show that there is no conflict between non-epistemic reasons for belief and epistemic standards for inference. I therefore only undertake here to provide what I take to be a plausible presumptive case for thinking that there are normative non-epistemic reasons for belief; I do not undertake to respond to all important objections to the view. See also Leary (2017, section 2) for a clear, brief, and (I think) convincing reply to the aim-of-belief argument against the possibility of non-epistemic normative reasons for belief.

P2 could be read as the claim that I have a (possibly defeated) normative reason to take the means to achieve peace of mind, or it could be read as the claim that I have all-things-considered normative reason to do so. I think the inference could go through either way, but for the purpose of the example I’ll stipulate that it is to be read as an all-things-considered normative reason or ought.

The conclusion here follows from P1 and P2, provided that the following general principle is correct. I think it is correct, but defending it is beyond the scope of this paper:

Necessarily, for all S, φ, ψ: if S has (a normative reason or) all-things-considered reason to φ, and ψ-ing is necessary for φ-ing, then S has (a normative reason or) all-things-considered reason for ψ-ing.

This principle is true in part because the claim that ψ-ing is necessary for φ-ing is one of the considerations going into the determination that S has normative reason or all-things-considered reason for φ-ing.

The case is similar to the central self-fulfilling prophecy case in Sharadin (2016), which Sharadin presents as a counterexample to Exclusivity, a Transparency-like principle. Sharadin also presents plausible replies to a number of objections against the psychological possibility of belief-formation on non-evidential grounds. I have argued elsewhere, however, that in Sharadin’s case the belief-formation is evidentially based, so I don’t think it is a genuine counterexample to Transparency, and I won’t rely on it here.

No doubt the error theory will need to be filled in further, for example with an account of the relation between subjects’ accepted norms for belief-formation, their conception of the state of belief, and the state of belief itself. But that will have to wait for another occasion.

This isn’t the place to go into the analysis of the basing relation, but various analyses of the basing relation would yield this result. The causal accounts I discuss in Bondy (2016) would yield this result, for example. See also Bondy and Carter (2018), where we explain various casual and doxastic accounts of the basing relation, as well as what we call a “justificationist” account.

Perhaps it can do so in some kinds of cases—say, in cases where S has an epistemically justified meta-belief MB to the effect that a lower-level belief B is epistemically justified, and S lacks any direct evidence bearing on B’s truth. In such cases, it is plausible to hold that S’s epistemic justification for MB makes it the case that S is justified in holding B as well. But I am not proposing that justification for meta-normative beliefs in general is what generates the normative reason for engaging in the target activity, or for holding the target belief.

But see Bondy (2018) for discussion and defense of Guidance.

See Turri (2010) for examples of inferences with premises which provide solid evidence for the conclusion, but where the inference is drawn in a bad way and fails to doxastically justify belief in the conclusion.

References

Adler, J. (2002). Belief’s own ethics. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Alvarez, M. (2010). Kinds of reasons. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Audi, R. (2015). Rational belief: Structure, grounds, and intellectual virtue. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Biro, J., & Siegel, H. (2006). In defense of the objective epistemic approach to argumentation. Informal Logic, 26(1), 91–101.

Boghossian, P. (2014). What is inference? Philosophical Studies, 169, 1–18.

Bondy, P. (2016). Counterfactuals and epistemic basing relations. Pacific Philosophical Quarterly, 97(4), 542–569.

Bondy, P. (2018). Epistemic rationality and epistemic normativity. New York: Routledge.

Bondy, P., & Carter, J. A. (2018). The basing relation and the impossibility of the debasing demon. American Philosophical Quarterly, 55(3), 203–215.

Broome, J. (2013). Rationality through reasoning. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Broome, J. (2014). Comments on Boghossian. Philosophical Studies, 169, 19–25.

Dancy, J. (2000). Practical reality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dougherty, T. (Ed.). (2011). Evidentialism and its discontents. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Feldman, R. (2000). The ethics of belief. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 60, 667–695.

Foley, R. (1987). The theory of epistemic rationality. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

Foley, R. (1993). Working without a net: A study of egocentric rationality. New York: Oxford University Press.

Foley, R. (2008). An epistemology that matters. In P. Weithman (Ed.), Liberal faith: Essays in honor of Philip Quinn (pp. 43–55). Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press.

Freeman, J. (2005). Acceptable premises: An epistemic approach to an informal logic problem. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gibbons, J. (2013). The norm of belief. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ginet, C. (2001). Deciding to believe. In M. Steup (Ed.), Knowledge, truth, and duty. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ginet, C. (2005a). Infinitism is not the solution to the regress problem. In M. Steup & E. Sosa (Eds.), Contemporary debates in epistemology (pp. 140–149). Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Ginet, C. (2005b). Reply to Klein. In M. Steup & E. Sosa (Eds.), Contemporary debates in epistemology (pp. 153–155). Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Goldman, A. (1999). Knowledge in a social world. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Goldman, A. (2003). An epistemological approach to argumentation. Informal Logic, 23(1), 51–63.

Hazlett, A. (2013). A Luxury of the understanding: On the value of true belief. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hitchcock, D. (2006). Informal logic and the concept of argument. In D. Jaquette (Ed.), Philosophy of logic (pp. 101–129). Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Hitchcock, D. (forthcoming). We justify questions, so how does that work? In 2018 conference of the international society for the study of argumentation. Keynote Address.

James, W. (1949). The will to believe. In W. James (Ed.), Essays in pragmatism (pp. 88–109). New York: Hafner (Originally published in 1896).

Johnson, R. (2000). Manifest rationality: A pragmatic theory of argument. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Kelly, T. (2002). The rationality of belief and some other propositional attitudes. Philosophical Studies, 110(2), 163–196.

Klein, P. (2005). Infinitism is the solution to the regress problem. In M. Steup & E. Sosa (Eds.), Contemporary debates in epistemology (pp. 131–140). Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Klein, P. (2007a). Human knowledge and the infinite progress of reasoning. Philosophical Studies: An International Journal for Philosophy in the Analytic Tradition., 134(1), 1–17.

Klein, P. (2007b). How to be an infinitist about doxastic justification. Philosophical Studies: An International Journal for Philosophy in the Analytic Tradition., 134(1), 25–29.

Leary, S. (2017). In defense of practical reasons for belief. Australasian Journal of Philosophy., 95(3), 529–542.

Leite, A. (2007). Epistemic instrumentalism and reasons for belief: A reply to Tom Kelly’s “Epistemic rationality as instrumental rationality: A critique”. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 75(2), 456–464.

Littlejohn, C. (2012). Justification and the truth-connection. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lord, E. (2015). Acting for the right reasons, abilities, and obligations. In R. Shafer-Landau (Ed.), Oxford studies in metaethics (Vol. 10). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lumer, C. (2005a). Introduction: The epistemological approach to argumentation—A map. Informal Logic, 25(3), 189–212.

Lumer, C. (2005b). The epistemological theory of argument—How and why? Informal Logic., 25(3), 213–243.

Markovits, J. (2011). Internal reasons and the motivating intuition. In M. Brady (Ed.), New waves in metaethics (pp. 141–165). New York: Palgrave.

McCormick, M. (2015). Believing against the evidence: Agency and the ethics of belief. New York: Routledge.

McHugh, C., & Way, J. (2018). What Is good reasoning? Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 96, 153–174.

Neta, R. (2013). What is an inference? Philosophical Issues, 23, 388–407.

Parfit, D. (2011). In S. Sheffler (Ed.), On what matters (Vol. 1). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pinto, R. (2001). Argument, inference and dialectic: Collected papers on informal logic. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Raz, J. (2009). Reasons: Practical and adaptive. In D. Sobel & S. Wall (Eds.), Reasons for action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Reisner, A. (2008). Weighing pragmatic and evidential reasons for belief. Philosophical Studies, 138(1), 17–27.

Reisner, A. (2009). The possibility of pragmatic reasons for belief and the wrong kind of reasons problem. Philosophical Studies, 145(2), 257–272.

Setiya, K. (2013). Epistemic agency: Some doubts. Philosophical Issues, 23, 179–198.

Shah, N. (2003). How truth governs belief. Philosophical Review, 112(4), 447–482.

Shah, N. (2006). A new argument for evidentialism. The Philosophical Quarterly., 56(225), 481–498.

Shah, N. (2013). Why we reason the way we do. Philosophical Issues., 23(1), 311–325.

Shah, N., & Velleman, D. (2005). Doxastic deliberation. The Philosophical Review, 114(4), 497–534.

Sharadin, N. (2016). Nothing but the evidential considerations? Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 94(2), 343–361.

Sorenson, R. (1991). ‘P, therefore P’ without circularity. The Journal of Philosophy., 88(5), 245–266.

Sosa, E. (2007). A virtue epistemology: Apt belief and reflective knowledge (Vol. 1). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stroud, S. (2006). Epistemic partiality in friendship. Ethics., 116(3), 498–524.

Turri, J. (2010). On the relation between propositional and doxastic justification. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 80(2), 312–326.

Turri, J., Rose, D., & Buckwalter, W. (2018). Choosing and refusing: Doxastic voluntarism and folk psychology. Philosophical Studies, 175, 2507–2537.

Velleman, D. (2000). The possibility of practical reason. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Way, J. (2017). Reasons as premises of good reasoning. Pacific Philosophical Quarterly, 98, 251–270.

Wedgwood, R. (2002). The aim of belief. Philosophical Perspectives., 16, 267–296.

Wedgwood, R. (2012). Justified inference. Synthese, 189, 273–295.

Williams, B. (1973). Deciding to believe. In B. Williams (Ed.), Problems of the self. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Williams, B. (1981). Internal and external reasons. In B. Williams (Ed.), Moral Luck (pp. 101–113). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wright, C. (2014). Comment on Paul Boghossian, “What is inference”. Philosophical Studies, 169, 27–37.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to audiences at Dalhousie University, the University of Florida, Wichita State University, and Brandon University, where earlier versions of this paper were presented. Particular thanks to Daniel Coren, Greg Ray, John Palmer, Jamie Ahlberg, Jeff Hershfield, and three blind referees for this journal, for very useful critical discussion and comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bondy, P. The epistemic norm of inference and non-epistemic reasons for belief. Synthese 198, 1761–1781 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-019-02163-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-019-02163-3