Abstract

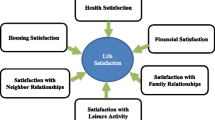

The Chinese government has launched a series of health reforms to establish universal health insurance coverage, particularly for vulnerable groups, including middle-aged and older adults. However, the current public health insurance system is highly fragmented, consisting of different programs with different levels of premiums and benefits. We analyse whether the universal health insurance system increases the life satisfaction of middle-aged and older Chinese people and to what extent the type of health insurance affects the life satisfaction of this group. Our study is based on data from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study, a nationally representative longitudinal survey of Chinese aged 45 and above, in 2011, 2013, and 2015. We find that the life satisfaction of middle-aged and older adults does not depend on having any health insurance coverage but varies with the type of health insurance coverage, controlling for potential confounding variables such as health status, occupation, hukou status, and other demographic variables. Individuals covered by the most generous program, the Government Medical Insurance, reported a higher life satisfaction. In comparison, individuals covered by the Urban Employee Medical Insurance, the Urban Resident Medical Insurance, and the New Rural Cooperative Scheme reported a lower life satisfaction by 0.155, 0.106, and 0.112 standard deviations, respectively. Our results suggest that establishing a more equitable health insurance system should be the next step in health reforms in China.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Funding sources differ across health insurance types. The UEMI is funded by an 8% payroll contribution, of which 6% are paid by employers and 2% by employees. The URBMI receives 70% of its funding from the government subsidies and 30% from individual premiums. The NCMS is 80% is founded by government subsidies and 20% by individual premium The GMI is 100% founded by the government (World Bank 2010).

The reimbursement rate of health insurance depends on the types of health insurance, the individual’s retirement status, the costs of medical services, and the tier of medical institutes. Here we describe the reimbursement level of first-tier medical institutes (e.g., county hospital). Please see details at https://beijing.chashebao.com/yiliao/12149.html.

See Zhao et al. (2013) for details of the CHARLS survey design and sampling method.

In this study, the terms ‘life satisfaction’, ‘happiness’, and ‘subjective wellbeing’ are used interchangeably, although differences in these concepts have been noticed (Diener 2006).

Very few respondents reported to be completely satisfied (3.2%) or not at all satisfied (2.8%). We have therefore grouped the five possible responses into three categories.

A few respondents reported being covered by multiple health insurance programs. For these respondents, we applied the questions of health insurance type in reimbursement of expenses in outpatient and inpatient services to double-check and identify their status of health insurance coverage.

We note that some regions or provinces have started to merge the NCMS and the URBMI into the URRMI before 2015 (only 2% reported to be covered by the URRMI in our sample). Also, we note that the URBMI, URRMI and NCMS have been merged into one scheme in some regions since 2015 but many CHARLS respondents reported to be covered by URBMI (16.7%) and NCMS (67.9%). We used all available CHARLS data to verify the respondents’ health insurance type based on the health insurance scheme they report directly, and the health insurance types they report for use or plan to use in reimbursement after using medical services. Based on the CHARLS questionnaire, we cannot assess whether the respondents know that their health insurance scheme has been merged and whether they report their health insurance types correctly. Given that our main results show that the generous GMI is associated with higher life satisfaction, the integration of the less generous NCMS, URBMI and URRMI would not affect our main results.

We group the responses to self-reported health status into two categories: poor health and other. Very few respondents reported having a very poor (4%) or very good health status (8%), while more than a half reported having a fair health status. We combined the answers “very poor health” and “poor health” into one category called “poor health”, and while “other” includes “very good”, “good” and “fair” health. We conducted robustness tests using three categories of self-reported health status in the model (poor health, fair health, good health), and the results are very similar to our main results in Table 4.

There are slight differences in the questions related to difficulty of performing daily activities in the three waves of CHARLS. Hence, we only use those ADL and IADL questions that are available in all three waves.

To better capture the effects of self-reported health status as a mediator, we use three categories of self-reported health status in the model: poor health status (24.2%), fair health status (52.7%) and good health status (23.1%). We apply an ordered fixed effects model in the first step of Table 6.

Another potential mediator in this study is the utilisation of medical services (e.g., outpatient and inpatient services). However, middle-aged and older adults in CHARLS reported relatively low usage of medical services. 22.9% reported using outpatient services in the last month, while 14% reported inpatient services uses in the last year. We tested the relationship between utilisation of medical services and health insurance and found no significant correlation.

We choose this age split because the official retirement age is 60 for males in the Employees’ Basic Pension and for males and females in the Residents’ Basic Pension and retirees are eligible to receive pensions after their retirement (The State Council of China 1978). Age 60 also gives a good sample split. 50% of the respondents in our sample are aged 60 and above.

References

Appleton, S., & Song, L. (2008). Life satisfaction in urban China: Components and determinants. World Development, 36(11), 2325–2340.

Babiarz, K. S., Miller, G., Yi, H., Zhang, L., & Rozelle, S. (2010). New evidence on the impact of China’s New Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme and its implications for rural primary healthcare: Multivariate difference-in-difference analysis. BMJ, 341, c5617.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173.

Bartolini, S., & Sarracino, F. (2015). The dark side of Chinese growth: Declining social capital and well-being in times of economic boom. World Development, 74, 333–351.

Blackwell, M., Iacus, S., King, G., & Porro, G. (2009). CEM: Coarsened exact matching in Stata. The Stata Journal, 9(4), 524–546.

Blanchflower, D. G., & Oswald, A. J. (2004). Well-being over time in Britain and the USA. Journal of Public Economics, 88(7–8), 1359–1386.

Cai, F. (2011). Hukou system reform and unification of rural–urban social welfare. China & World Economy, 19(3), 33–48.

Cai, F., & Wang, M. (2010). Growth and structural changes in employment in transition China. Journal of Comparative Economics, 38(1), 71–81.

Chen, C. (2001). Aging and life satisfaction. Social Indicators Research, 54(1), 57–79.

Chen, Y., & Jin, G. Z. (2012). Does health insurance coverage lead to better health and educational outcomes? Evidence from rural China. Journal of Health Economics, 31(1), 1–14.

Cheng, L., Liu, H., Zhang, Y., Shen, K., & Zeng, Y. (2015). The impact of health insurance on health outcomes and spending of the elderly: Evidence from China’s new cooperative medical scheme. Health Economics, 24(6), 672–691.

Chyi, H., & Mao, S. (2012). The determinants of happiness of China’s elderly population. Journal of Happiness Studies, 13(1), 167–185.

Clark, A. E., & Oswald, A. J. (1996). Satisfaction and comparison income. Journal of Public Economics, 61(3), 359–381.

Connidis, I. A., & McMullin, J. A. (1993). To have or have not: Parent status and the subjective well-being of older men and women. The Gerontologist, 33(5), 630–636.

Di Tella, R., MacCulloch, R. J., & Oswald, A. J. (2001). Preferences over inflation and unemployment: Evidence from surveys of happiness. American Economic Review, 91(1), 335–341.

Diener, E. (2006). Guidelines for national indicators of subjective well-being and ill-being. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 1(2), 151–157.

Diener, E., & Biswas-Diener, R. (1999). Income and subjective well-being: Will money make us happy? Unpublished manuscript, Department of Psychology, University of Illinois.

Ding, Y. (2017). Personal life satisfaction of China’s rural elderly: Effect of the new rural pension programme. Journal of International Development, 29(1), 52–66.

Easterlin, R. A. (1974). Does economic growth improve the human lot? Some empirical evidence. In P. A. David & M. W. Reder (Eds.), Nations and households in economic growth (pp. 89–125). Cambridge, MA: Academic Press.

Easterlin, R. A. (2004). The economics of happiness. Daedalus, 133(2), 26–33.

Easterlin, R. A. (2012). Life satisfaction of rich and poor under socialism and capitalism. International Journal of Happiness and Development, 1(1), 112–126.

Easterlin, R. A. (2013). Happiness, growth, and public policy. Economic Inquiry, 51(1), 1–15.

Easterlin, R. A., Morgan, R., Switek, M., & Wang, F. (2012). China’s life satisfaction, 1990–2010. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(25), 9775–9780.

Easterlin, R. A., Wang, F., & Wang, S. (2017). Growth and happiness in China, 1990–2015. World Happiness Report, 2017, 48.

Eggleston, K., Ling, L., Meng, Q., Lindelow, M., & Wagstaff, A. (2008). Health service delivery in China: A literature review. Health Economics, 17, 149–165.

Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A., & Frijters, P. (2004). How important is methodology for the estimates of the determinants of happiness? The Economic Journal, 114(497), 641–659.

Fitzpatrick, A. L., Powe, N. R., Cooper, L. S., Ives, D. G., & Robbins, J. A. (2004). Barriers to health care access among the elderly and who perceives them. American Journal of Public Health, 94(10), 1788–1794.

Frey, B. S., & Stutzer, A. (1999). Measuring preferences by subjective well-being. Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics (JITE)/Zeitschrift für die gesamte Staatswissenschaft, 155(4), 755–778.

Gao, J., Qian, J., Tang, S., Eriksson, B. O., & Blas, E. (2002). Health equity in transition from planned to market economy in China. Health Policy and Planning, 17(suppl_1), 20–29.

Garfield, R., Majerol, M., Damico, A., & Foutz, J. (2016). The uninsured: a primer. Key facts about health insurance and the uninsured in America. Menlo Park, CA: The Henry James Kaiser Family Foundation.

Graham, C. (2012). Happiness around the world: The paradox of happy peasants and miserable millionaires. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Graham, C., Higuera, L., & Lora, E. (2011). Which health conditions cause the most unhappiness? Health Economics, 20(12), 1431–1447.

Graham, C., & Lora, E. (Eds.). (2010). Paradox and perception: Measuring quality of life in Latin America. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Graham, C., & Pettinato, S. (2002). Frustrated achievers: Winners, losers and subjective well-being in new market economies. Journal of Development Studies, 38(4), 100–140.

Graham, C., Zhou, S., & Zhang, J. (2017). Happiness and health in China: The paradox of progress. World Development, 96, 231–244.

Guriev, S., & Melnikov, N. (2018). Happiness convergence in transition countries. Journal of Comparative Economics, 46(3), 683–707.

Gwozdz, W., & Sousa-Poza, A. (2010). Ageing, health and life satisfaction of the oldest old: An analysis for Germany. Social Indicators Research, 97(3), 397–417.

Halaby, C. N. (2004). Panel models in sociological research: Theory into practice. Annual Review of Sociology, 30, 507–544.

Hayes, N., & Joseph, S. (2003). Big 5 correlates of three measures of subjective well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 34(4), 723–727.

Ho, D. E., Imai, K., King, G., & Stuart, E. A. (2007). Matching as nonparametric preprocessing for reducing model dependence in parametric causal inference. Political Analysis, 15(3), 199–236.

Hsiao, W. C. (2004). Disparity in health: The underbelly of China’s economic development. Harvard China Review, 5(1), 64–70.

Iacus, S. M., King, G., & Porro, G. (2012). Causal inference without balance checking: Coarsened exact matching. Political Analysis, 20(1), 1–24.

Infurna, F. J., Wiest, M., Gerstorf, D., Ram, N., Schupp, J., Wagner, G. G., et al. (2017). Changes in life satisfaction when losing one’s spouse: Individual differences in anticipation, reaction, adaptation and longevity in the German Socio-economic Panel Study (SOEP). Ageing & Society, 37(5), 899–934.

Jibeen, T. (2014). Personality traits and subjective well-being: Moderating role of optimism in university employees. Social Indicators Research, 118(1), 157–172.

Jin, Q., Pearce, P., & Hu, H. (2018). The study on the satisfaction of the elderly people living with their children. Social Indicators Research, 140(3), 1159–1172.

Keng, S. H., & Wu, S. Y. (2014). Living happily ever after? The effect of Taiwan’s National Health Insurance on the happiness of the elderly. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15(4), 783–808.

Kenworthy, L., & Pontusson, J. (2005). Rising inequality and the politics of redistribution in affluent countries. Perspectives on Politics, 3(3), 449–471.

Knight, J., & Gunatilaka, R. (2010). The rural–urban divide in China: Income but not happiness? The Journal of Development Studies, 46(3), 506–534.

Li, J., & Raine, J. W. (2014). The time trend of life satisfaction in China. Social Indicators Research, 116(2), 409–427.

Li, S., Sato, H., & Sicular, T. (Eds.). (2013). Rising inequality in China: Challenges to a harmonious society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Li, Y., Wu, Q., Liu, C., Kang, Z., Xie, X., Yin, H., et al. (2014). Catastrophic health expenditure and rural household impoverishment in China: What role does the new cooperative health insurance scheme play? PLoS ONE, 9(4), e93253.

Liu, H., & Zhao, Z. (2014). Does health insurance matter? Evidence from China’s urban resident basic medical insurance. Journal of Comparative Economics, 42(4), 1007–1020.

McWilliams, J. M., Zaslavsky, A. M., Meara, E., & Ayanian, J. Z. (2004). Health insurance coverage and mortality among the near-elderly. Health Affairs, 23(4), 223–233.

Meng, Q., Fang, H., Liu, X., Yuan, B., & Xu, J. (2015). Consolidating the social health insurance schemes in China: Towards an equitable and efficient health system. The Lancet, 386(10002), 1484–1492.

Ministry of Health in China. (2004). Research on national health services: An analysis report of National Health Services Survey in 2003. Beijing: Xie He Medical University Press (in Chinese).

National Bureau of Statistics of China. (2018). Retrieved October 14, 2019 from http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/.

Ng, S. T., Tey, N. P., & Asadullah, M. N. (2017). What matters for life satisfaction among the oldest-old? Evidence from China. PLoS ONE, 12(2), e0171799.

Plümper, T., & Troeger, V. E. (2007). Efficient estimation of time-invariant and rarely changing variables in finite sample panel analyses with unit fixed effects. Political Analysis, 15(2), 124–139.

Provincial Government of Shandong Province. (2014). Implementation plan for integrating basic medical insurance for urban and rural residents in Shandong Province. Retrieved August 30, 2019 from http://hrss.shandong.gov.cn/articles/ch00580/201411/40037.shtml.

Qi, S., & Zhou, S. (2010). The influence of income, health and Medicare insurance on the happiness of the elderly in China. Journal of Public Management, 1, 100–107 (in Chinese).

Shi, L., & Zhang, D. (2013). China’s new rural cooperative medical scheme and underutilization of medical care among adults over 45: Evidence from CHARLS pilot data. The Journal of Rural Health, 29(s1), s51–s61.

Sidel, V. W. (1993). New lessons from China: Equity and economics in rural health care. American Journal of Public Health, 83(12), 1665–1666.

Sin, N. L., Yaffe, K., & Whooley, M. A. (2015). Depressive symptoms, cardiovascular disease severity, and functional status in older adults with coronary heart disease: The heart and soul study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 63(1), 8–15.

Sjöberg, O. (2010). Social insurance as a collective resource: Unemployment benefits, job insecurity and subjective well-being in a comparative perspective. Social Forces, 88(3), 1281–1304.

Smyth, R., Nielsen, I., & Zhai, Q. (2010). Personal well-being in urban China. Social Indicators Research, 95(2), 231.

Su, M., Zhou, Z., Si, Y., Wei, X., Xu, Y., Fan, X., et al. (2018). Comparing the effects of China’s three basic health insurance schemes on the equity of health-related quality of life: Using the method of coarsened exact matching. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 16(1), 41.

Sun, J., Deng, S., Xiong, X., & Tang, S. (2014). Equity in access to healthcare among the urban elderly in China: Does health insurance matter? The International Journal of Health Planning and Management, 29(2), e127–e144.

Tang, Z. (2014). They are richer but are they happier? Subjective well-being of Chinese citizens across the reform era. Social Indicators Research, 117(1), 145–164.

The Office of State Council of China. (2000). The Office of the State Council forwarded the notice of the Ministry of Finance and the Ministry of Labour and Social Security on the implementation of the medical assistance for the government employee. Retrieved July 25, 2019 from http://www.gov.cn/gongbao/content/2000/content_60249.htm.

The State Council of China. (1978). Interim regulation on workers’ retirement and resignations. Retrieved January 23, 2020 from http://www.npc.gov.cn/wxzl/wxzl/2000-12/07/content_9552.htm.

Tian, S., Zhou, Q., & Pan, J. (2015). Inequality in social health insurance programmes in China: A theoretical approach. Journal of Asian Public Policy, 8(1), 56–68.

Tran, N. L. T., Wassmer, R. W., & Lascher, E. L. (2017). The health insurance and life satisfaction connection. Journal of Happiness Studies, 18(2), 409–426.

Van Doorslaer, E., O’Donnell, O., Rannan-Eliya, R. P., Somanathan, A., Adhikari, S. R., Garg, C. C., et al. (2007). Catastrophic payments for health care in Asia. Health Economics, 16(11), 1159–1184.

Veenhoven, R. (1996a). Developments in satisfaction-research. Social Indicators Research, 37(1), 1–46.

Veenhoven, R. (1996b). Happy life-expectancy. Social Indicators Research, 39(1), 1–58.

Veenhoven, R. (2002). Why social policy needs subjective indicators. Social Indicators Research, 58(1–3), 33–46.

Wagstaff, A., Lindelow, M., Jun, G., Ling, X., & Juncheng, Q. (2009). Extending health insurance to the rural population: An impact evaluation of China’s new cooperative medical scheme. Journal of Health Economics, 28, 1–29.

Wang, P., Pan, J., & Luo, Z. (2015). The impact of income inequality on individual happiness: Evidence from China. Social Indicators Research, 121(2), 413–435.

Wooden, M., & Li, N. (2014). Panel conditioning and subjective well-being. Social Indicators Research, 117(1), 235–255.

World Bank. (2016). Live long and prosper: Aging in East Asia and Pacific. Washington, DC: World Bank.

World Health Organization. (2015). China country assessment report on ageing and health. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Wu, X., & Li, J. (2013). Economic growth, income inequality and subjective well-being: Evidence from China. Population Studies Center Research Report, 13–796, 29.

Wu, L. H., & Tsay, R. M. (2018). The search for happiness: Work experiences and quality of life of older Taiwanese men. Social Indicators Research, 136(3), 1031–1051.

Yi, Z., & Vaupel, J. W. (2002). Functional capacity and self-evaluation of health and life of oldest old in China. Journal of Social Issues, 58(4), 733–748.

Yip, W., & Hsiao, W. C. (2009). Non-evidence-based policy: How effective is China’s new cooperative medical scheme in reducing medical impoverishment? Social Science and Medicine, 68, 201–209.

Yip, W. C. M., Hsiao, W. C., Chen, W., Hu, S., Ma, J., & Maynard, A. (2012). Early appraisal of China’s huge and complex health-care reforms. The Lancet, 379(9818), 833–842.

Yu, L., Yan, Z., Yang, X., Wang, L., Zhao, Y., & Hitchman, G. (2016). Impact of social changes and birth cohort on subjective well-being in Chinese older adults: A cross-temporal meta-analysis, 1990–2010. Social Indicators Research, 126(2), 795–812.

Zhang, C., Lei, X., Strauss, J., & Zhao, Y. (2017). Health insurance and health care among the mid-aged and older Chinese: Evidence from the national baseline survey of CHARLS. Health Economics, 26(4), 431–449.

Zhao, Y., Strauss, J., Yang, G., Giles, J., Hu, P., Hu, Y., et al. (2013). China health and retirement longitudinal study 2011–2012: National baseline users’ guide. Beijing: School of National Development, Peking University.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the financial support from the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence in Population Ageing Research (CEPAR). We are grateful for comments received from John Piggott, Guy Mayraz, Jeromey Temple and Peter McDonald AM and from participants at the 5th Annual Workshop on Population Ageing and the Chinese Economy. The authors are responsible for all remaining errors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, S., Hanewald, K. Life Satisfaction of Middle-Aged and Older Chinese: The Role of Health and Health Insurance. Soc Indic Res 160, 601–624 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-020-02390-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-020-02390-z