Abstract

Disability is a varied experience resulting from the interaction of multiple factors: health conditions, personal, and environmental factors. People with Disabilities face various forms of discrimination within the healthcare sector, including the lack of accessible and appropriate services; information in accessible formats; coverage of communication needs; and access to information and communication technologies. Another area of hindrance is accessing sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services. This scoping review aims to identify facilitators and barriers related to accessing SRH services and the experiences of people with sensory impairment (PwSI) in them. The review includes 37 articles reporting on facilitators and barriers to SRH services. Findings include less access to SRH and awareness in how to access SRH services, mainly among young people, and less comprehensive knowledge about modern contraceptive methods possibly determined by the lack of adequate and inclusive sexual information. These results support the idea of including accessible SRH materials, training providers on the needs of people with sensory disabilities, removing barriers to sexuality education and health services, to address the disadvantages faced by PwSI and provide them with access to health care which is a basic right.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Women reproductive age is define according to WHO “De facto population of women of reproductive age (15–49 years) in a country, area or region” [17].

References

World Health Organization, WHO: Global Report on Health Equity for Persons with Disabilities (2022). https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1481486/retrieve

WHO: World report on vision (2019). https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241516570

WHO: World report on hearing (2021). https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/world-report-on-hearing

Bogart, K.R., Rottenstein, A., Lund, E.M., Bouchard, L.: Who self-identifies as disabled? An examination of impairment and contextual predictors. Rehabil. Psychol. 62(4), 53–562 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1037/rep0000132

Terzi, L.: The social model of disability: a philosophical critique. J. Appl. Philos. 21(2), 141–157 (2004)

Lawson, A., Beckett, A.E.: The social and human rights models of disability: towards a complementarity thesis. Int. J. Hum. Rights 25(2), 348–379 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1080/13642987.2020.1783533

Palacios, A.: El modelo social de la discapacidad: orígenes, caracterización y plasmación en la Convención Internacional sobre los Derechos de las Personas con Discapacidad. Ediciones, Madrid (2008)

Naciones Unidas: Convención sobre los derechos de las personas con discapacidad. Ginebra (2006)

United Nations Population Fund: Women and young persons with disabilities. Guidelines for providing rights‐based and gender‐responsive services to address gender‐based violence and sexual and reproductive health and rights (2018)

WHO: Promoting sexual and reproductive health for persons with disabilities: WHO/UNFPA guidance note (2009).

Malihi, Z.A., Fanslow, J.L., Hashemi, L., Gulliver, P.J., McIntosh, T.K.D.: Prevalence of nonpartner physical and sexual violence against people with disabilities. Am. J. Prev. Med. 61(3), 329–337 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2021.03.016

Alhusen, J.L., Bloom, T., Anderson, J., Hughes, R.B.: Intimate partner violence, reproductive coercion, and unintended pregnancy in women with disabilities. Disabil. Health J. 13(2), 100849 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2019.100849

McGowan, J., Elliott, K.: Targeted violence perpetrated against women with disability by neighbours and community members. Womens. Stud. Int. Forum (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2019.102270

Nguyen, A.: Challenges for women with disabilities accessing reproductive health care around the world: a scoping review. Sex. Disabil. 38(3), 371–388 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-020-09630-7

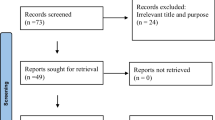

Tricco, A.C., et al.: PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 169(7), 467–473 (2018)

Page, M.J., et al.: The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int. J. Surg. 88, 105906 (2021)

World Health Organization: Women of reproductive age (15–49 years) population (thousands) (2022). https://www.who.int/data/gho/indicator-metadata-registry/imr-details/women-of-reproductive-age-(15-49-years)-population-(thousands). Accessed 10 May 2022

United Nations Population Fund: Sexual and Reproductive Health 2022. https://www.unfpa.org/sexual-reproductive-health#summery105857

Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z., Elmagarmid, A.: Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 5(1), 1–10 (2016)

O’Brien, B.C., Harris, I.B., Beckman, T.J., Reed, D.A., Cook, D.A.: Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad. Med. 89(9), 1245–1251 (2014)

Ramke, J., Palagyi, A., Jordan, V., Petkovic, J., Gilbert, C.E.: Using the STROBE statement to assess reporting in blindness prevalence surveys in low and middle income countries. PLoS ONE 12(5), e0176178 (2017)

Nawijn, F., Ham, W.H.W., Houwert, R.M., Groenwold, R.H.H., Hietbrink, F., Smeeing, D.P.J.: Quality of reporting of systematic reviews and meta-analyses in emergency medicine based on the PRISMA statement. BMC Emerg. Med. 19(1), 1–8 (2019)

Baethge, C., Goldbeck-Wood, S., Mertens, S.: SANRA—a scale for the quality assessment of narrative review articles. Res. Integr. Peer Rev. 4(1), 1–7 (2019)

Groce, N.E., Rohleder, P., Eide, A.H., MacLachlan, M., Mall, S., Swartz, L.: HIV issues and people with disabilities: a review and agenda for research. Soc. Sci. Med. 77(1), 31–40 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.10.024

Mprah, W.K.: Knowledge and use of contraceptive methods amongst deaf people in Ghana. Afr. J. Disabil. 2(1), 43 (2013). https://doi.org/10.4102/ajod.v2i1.43

Beyene, G.A., Munea, A.M., Fekadu, G.A.: Modern contraceptive use and associated factors among women with disabilities in Gondar city, Amhara region, north west Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. Afr. J. Reprod. Health 23(2), 101–109 (2019). https://doi.org/10.29063/ajrh2019/v23i2.10

Gibson, B.E., Mykitiuk, R.: Health care access and support for disabled women in Canada: falling short of the UN convention on the rights of persons with disabilities: a qualitative study. Womens Heal. Issues 22(1), E111–E118 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2011.07.011

Burke, E., Kébé, F., Flink, I., van Reeuwijk, M., le May, A.: A qualitative study to explore the barriers and enablers for young people with disabilities to access sexual and reproductive health services in Senegal. Reprod. Health Matters 25(50), 43–54 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1080/09688080.2017.1329607

Horner-Johnson, W., Darney, B.G., Kulkarni-Rajasekhara, S., Quigley, B., Caughey, A.B.: Pregnancy among US women: differences by presence, type, and complexity of disability. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 214(4), 529.e1-529.e9 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2015.10.929

De Beaudrap, P., et al.: HandiVIH-A population-based survey to understand the vulnerability of people with disabilities to HIV and other sexual and reproductive health problems in Cameroon: protocol and methodological considerations. BMJ Open 6, 2 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008934

Dissanayake, M.V., Darney, B.G., Caughey, A.B., Horner-Johnson, W.: Miscarriage occurrence and prevention efforts by disability status and type in the United States. J. Women’s Heal. 29(3), 345–352 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2019.7880

Mprah, W.K., Anafi, P., Addai Yeaboah, P.Y.: Exploring misinformation of family planning practices and methods among deaf people in Ghana. Reprod. Health Matters 25(50), 20–30 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1080/09688080.2017.1332450

Kelly, S., Kapperman, G.: Sexual activity of young adults who are visually impaired and the need for effective sex education. J. Vis. Impair. Blind. 106(9), 519–526 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1177/0145482X1210600903

Heiman, E., Haynes, S., McKee, M.: Sexual health behaviors of Deaf American Sign Language (ASL) users. Disabil. Health J. 8(4), 579–585 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2015.06.005

Jamali, M.Z.: Disability measurement and uptake of sexual and reproductive health services in Malawi. University of Southampton (2020)

Kassa, T.A., Luck, T., Birru, S.K., Riedel-Heller, S.G.: Sexuality and sexual reproductive health of disabled young people in Ethiopia. Sex. Transm. Dis. 41(10), 583–588 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000182

Tanabe, M., Nagujjah, Y., Rimal, N., Bukania, F., Krause, S.: Intersecting sexual and reproductive health and disability in humanitarian settings: risks, needs, and capacities of refugees with disabilities in Kenya, Nepal, and Uganda. Sex. Disabil. 33(4), 411–427 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-015-9419-3

Schindeler, T.L., Aldersey, H.M.: Community-based rehabilitation programming for sex(uality), sexual abuse prevention, and sexual and reproductive health: a scoping review. Disabil. CBR Incl. Dev. 30(1), 5 (2019). https://doi.org/10.5463/dcid.v30i1.784

Shandra, C.L., Shameem, M., Ghori, S.J.: Disability and the context of boys’ first sexual intercourse. J. Adolesc. Heal. 58(3), 302–309 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.10.013

Haynes, R.M., Boulet, S.L., Fox, M.H., Carroll, D.D., Courtney-Long, E., Warner, L.: Contraceptive use at last intercourse among reproductive-aged women with disabilities: an analysis of population-based data from seven states. Contraception 97(6), 538–545 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2017.12.008

Breman, J.G., Alilio, M.S., Mills, A.: Conquering the intolerable burden of malaria: what’s new, what’s needed: a summary. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 71(2), 1–15 (2004)

Carew, M.T., Hellum Braathen, S., Swartz, L., Hunt, X., Rohleder, P.: The sexual lives of people with disabilities within low- and middle-income countries: a scoping study of studies published in English. Glob. Health Action (2017). https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2017.1337342

Devine, A., et al.: ‘Freedom to go where I want’: improving access to sexual and reproductive health for women with disabilities in the Philippines. Reprod. Health Matters 25(50), 55–65 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1080/09688080.2017.1319732

Devkota, H.R., Kett, M., Groce, N.: Societal attitude and behaviors towards women with disabilities in rural Nepal: pregnancy, childbirth and motherhood. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 19, 1 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2171-4

Dean, L., Tolhurst, R., Khanna, R., Jehan, K.: ‘You’re disabled, why did you have sex in the first place?’ An intersectional analysis of experiences of disabled women with regard to their sexual and reproductive health and rights in Gujarat State, India. Glob. Health Action 10(sup2), 1290316 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2017.1290316

Mills, A.A.: Navigating sexual and reproductive health issues: voices of deaf adolescents in a residential school in Ghana. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 118, 105441 (2020)

Hunt, X., Carew, M.T., Braathen, S.H., Swartz, L., Chiwaula, M., Rohleder, P.: The sexual and reproductive rights and benefit derived from sexual and reproductive health services of people with physical disabilities in South Africa: beliefs of non-disabled people. Reprod. Health Matters 25(50), 66–79 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1080/09688080.2017.1332949

Devkota, H.R., Murray, E., Kett, M., Groce, N.: Healthcare provider’s attitude towards disability and experience of women with disabilities in the use of maternal healthcare service in rural Nepal. Reprod. Health 14, 1 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-017-0330-5

DeBeaudrap, P., Mouté, C., Pasquier, E., Mac-Seing, M., Mukangwije, P.U., Beninguisse, G.: Disability and access to sexual and reproductive health services in Cameroon: a mediation analysis of the role of socioeconomic factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16, 3 (2019). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16030417

Badu, E., Gyamfi, N., Opoku, M.P., Mprah, W.K., Edusei, A.K.: Enablers and barriers in accessing sexual and reproductive health services among visually impaired women in the Ashanti and Brong Ahafo Regions of Ghana. Reprod. Health Matters 26(54), 51–60 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1080/09688080.2018.1538849

Gartrell, A., Baesel, K., Becker, C.: ‘We do not dare to love’: women with disabilities’ sexual and reproductive health and rights in rural Cambodia. Reprod. Health Matters 25(50), 31–42 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1080/09688080.2017.1332447

Hameed, S., Maddams, A., Lowe, H., Davies, L., Khosla, R., Shakespeare, T.: From words to actions: systematic review of interventions to promote sexual and reproductive health of persons with disabilities in low- and middle-income countries. BMJ Glob. Heal. 5, 10 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002903

Mprah, W.K., Anafi, P., Sekyere, F.O.: Does disability matter? Disability in sexual and reproductive health policies and research in Ghana. Int. Q. Community Health Educ. 35(1), 21–35 (2014). https://doi.org/10.2190/IQ.35.1.c

Yimer, A.S., Modiba, L.M.: Modern contraceptive methods knowledge and practice among blind and deaf women in Ethiopia. A cross-sectional survey. BMC Womens. Health 19(1), 151 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-019-0850-y

Obasi, M., et al.: Sexual and reproductive health of adolescents in schools for people with disabilities. Pan Afr. Med. J. (2019). https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2019.33.299.18546

Rivera Drew, J.A., Short, S.E.: Disability and Pap Smear Receipt Among U.S. Women 2000 and 2005. Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health 42(4), 258–266 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1363/4225810

Kaplan, C.: Special issues in contraception: caring for women with disabilities. J. Midwifery Women’s Heal. 51(6), 450–456 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmwh.2006.07.009

Hayes, B.: Availability of appropriately packaged information on sexual health for people who are legally blind. Aust. J. Rural Health 7(3), 155–159 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1584.1999.00211.x

Raut, N.: Case studies on sexual and reproductive health of disabled women in Nepal. Asian J. Women’s Stud. 24(1), 140–151 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1080/12259276.2018.1424700

Mprah, W.: Perceptions about barriers to sexual and reproductive health information and services among deaf people in Ghana. Disabil. CBR Incl. Dev. (2013). https://doi.org/10.5463/dcid.v24i3.234

Rodríguez Domínguez, P.L., Mendoza Díaz, D.: Post-coital contraception in deaf adult women and teenagers. Rev. Med. Electrón. [Internet] 31(6) (2009)

Cho, S., Williams Crenshaw, K., McCall, L.: Toward a field of intersectionality studies: theory, applications, and praxis. Signs (Chic) 38(4), 785–810 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1086/669608

Grech, S.: Comment from the field: disability and the majority world: challenging dominant epistemologies. J. Lit. Cult. Disabil. Stud. 5(2), 217-219,227 (2011)

Barnes, C., Sheldon, A.: Disability, politics and poverty in a majority world context. Disabil. Soc. 25(7), 771–782 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2010.520889

Moodley, J., Graham, L.: The importance of intersectionality in disability and gender studies. Agenda (2015). https://doi.org/10.1080/10130950.2015.1041802

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Megan Evans and Nour Horanieh for assisting in the editing of the original manuscript and Katherinne Rivas-Castro for helping with the search strategy.

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by AB, JR, JB, and JR. The first draft of the manuscript was written by all authors, who commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Appendix 1. Example Search Strategy in Pubmed and Web of Science

Search terms | |

|---|---|

About health services | ((((((((Need*, Health Services) OR (“Health Services Need*”)) OR (“Target Populations”)) OR (Population*, Target)) OR (“Target Population”)) OR ((Needs) OR (“Target Population”))) OR (Needs and Demand, Health Services)) OR (Health Services Needs and Demand [MH])) |

About sexual and reproductive health | ((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((sexual and reproductive health[MH]) OR (sexual health[MH])) OR (reproductive health[MH])) OR (reproductive health service*)) OR (service*, reproductive health)) OR (Family Planning Services)) OR (Contraception)) OR (Contraceptive Devices)) OR (Contraceptive Agents)) OR (family planning*)) OR (contracept*)) OR (condom*)) OR (birth control)) OR (steriliz*)) OR (sterilis*)) OR (vasectomy*)) OR (women health[MH])) OR (women health service*)) OR (service*, women health)) OR (men’s health[MH])) OR (adolescent sexual health)) OR (youth sexual health)) OR (adolescent reproductive health)) OR (youth reproductive health)) OR (adolescent health)) OR (youth health)) OR (adolescent health services)) OR (youth friendly services)) OR (adolescent friendly services)) OR (youth program*)) OR (teenage* pregnancy) |

About sensory impairment | ((((((((((((((((((((“cortical deafness”) OR (cortical deafness)) OR (“Deaf-Blind Disorders”)) OR (Hearing Loss, Bilateral)) OR (acquired deafness)) OR (hearing loss)) OR (Deaf*)) OR (acoustic handicap*)) OR (acoustic disabili*)) OR (acoustic disable*)) OR (acoustic deficien*)) OR (acoustic impair*)) OR (acoustic loss*)) OR (hearing handicap*)) OR (hearing disabili*)) OR (hearing disable*)) OR (hearing deficien*)) OR (hearing impair*)) OR (hearing loss*)) OR (“hearing loss”)) OR (deafness) OR (¨acquired blindness¨) |

((((((((((((((((blind*) OR (“reduced vision”)) OR (“low vision”)) OR (visual handicap*)) OR (visual disabili*)) OR (visual disable*)) OR (visual deficien*)) OR (visual impair*)) OR (visual loss*)) OR (vision handicap*)) OR (vision disabili*)) OR (¨vision disable*¨)) OR (¨vision deficien*¨)) OR (¨vision impair*¨)) OR (“vision loss*”)) OR (“Blindness"[Mesh])) OR (“Disabled Persons"[MH]) |

# | Searches in Pubmed | Results |

|---|---|---|

1 | ((((((((((Need*, Health Services) OR (“Health Services Need*”)) OR (“Target Populations”)) OR (Population*, Target)) OR (“Target Population”)) OR ((Needs) OR (“Target Population”))) OR (Needs and Demand, Health Services)) OR (Health Services Needs and Demand [MH]))) AND ((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((sexual and reproductive health[MH]) OR (sexual health[MH])) OR (reproductive health[MH])) OR (reproductive health service*)) OR (service*, reproductive health)) OR (Family Planning Services)) OR (Contraception)) OR (Contraceptive Devices)) OR (Contraceptive Agents)) OR (family planning*)) OR (contracept*)) OR (condom*)) OR (birth control)) OR (steriliz*)) OR (sterilis*)) OR (vasectomy*)) OR (women health[MH])) OR (women health service*)) OR (service*, women health)) OR (men’s health[MH])) OR (adolescent sexual health)) OR (youth sexual health)) OR (adolescent reproductive health)) OR (youth reproductive health)) OR (adolescent health)) OR (youth health)) OR (adolescent health services)) OR (youth friendly services)) OR (adolescent friendly services)) OR (youth program*)) OR (teenage* pregnancy))) AND (((((((((((((((((((((((“cortical deafness”) OR (cortical deafness)) OR (“Deaf-Blind Disorders”)) OR (Hearing Loss, Bilateral)) OR (acquired deafness)) OR (hearing loss)) OR (Deaf*)) OR (acoustic handicap*)) OR (acoustic disabili*)) OR (acoustic disable*)) OR (acoustic deficien*)) OR (acoustic impair*)) OR (acoustic loss*)) OR (hearing handicap*)) OR (hearing disabili*)) OR (hearing disable*)) OR (hearing deficien*)) OR (hearing impair*)) OR (hearing loss*)) OR (“hearing loss”)) OR (deafness) OR (¨acquired blindness¨)) OR (((((((((((((((((blind*) OR (“reduced vision”)) OR (“low vision”)) OR (visual handicap*)) OR (visual disabili*)) OR (visual disable*)) OR (visual deficien*)) OR (visual impair*)) OR (visual loss*)) OR (vision handicap*)) OR (vision disabili*)) OR (¨vision disable*¨)) OR (¨vision deficien*¨)) OR (¨vision impair*¨)) OR (“vision loss*”)) OR (“Blindness"[Mesh])) OR (“Disabled Persons"[MH]))) OR (((((((“Trisomy 21”) OR (Mongolism)) OR (“Down’s Syndrome”)) OR (dyslexi*)) OR (asperger*)) OR (autism)) OR (Pervasive Child Development Disorders[MH]))) | 933 |

2 | (sexual and reproductive health[TIAB]) AND (((((((((((Need*, Health Services) OR (“Health Services Need*”)) OR (“Target Populations”)) OR (Population*, Target)) OR (“Target Population”)) OR ((Needs) OR (“Target Population”))) OR (Needs and Demand, Health Services)) OR (Health Services Needs and Demand [MH]))) AND ((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((sexual health[MH])) OR (reproductive health[MH])) OR (reproductive health service*)) OR (service*, reproductive health)) OR (Family Planning Services)) OR (Contraception)) OR (Contraceptive Devices)) OR (Contraceptive Agents)) OR (family planning*)) OR (contracept*)) OR (condom*)) OR (birth control)) OR (steriliz*)) OR (sterilis*)) OR (vasectomy*)) OR (women health[MH])) OR (women health service*)) OR (service*, women health)) OR (men’s health[MH])) OR (adolescent sexual health)) OR (youth sexual health)) OR (adolescent reproductive health)) OR (youth reproductive health)) OR (adolescent health)) OR (youth health)) OR (adolescent health services)) OR (youth friendly services)) OR (adolescent friendly services)) OR (youth program*)) OR (teenage* pregnancy))) AND (((((((((((((((((((((((“cortical deafness”) OR (cortical deafness)) OR (“Deaf-Blind Disorders”)) OR (Hearing Loss, Bilateral)) OR (acquired deafness)) OR (hearing loss)) OR (Deaf*)) OR (acoustic handicap*)) OR (acoustic disabili*)) OR (acoustic disable*)) OR (acoustic deficien*)) OR (acoustic impair*)) OR (acoustic loss*)) OR (hearing handicap*)) OR (hearing disabili*)) OR (hearing disable*)) OR (hearing deficien*)) OR (hearing impair*)) OR (hearing loss*)) OR (“hearing loss”)) OR (deafness) OR (¨acquired blindness¨)) OR (((((((((((((((((blind*) OR (“reduced vision”)) OR (“low vision”)) OR (visual handicap*)) OR (visual disabili*)) OR (visual disable*)) OR (visual deficien*)) OR (visual impair*)) OR (visual loss*)) OR (vision handicap*)) OR (vision disabili*)) OR (¨vision disable*¨)) OR (¨vision deficien*¨)) OR (¨vision impair*¨)) OR (“vision loss*”)) OR (“Blindness"[Mesh])) OR (“Disabled Persons"[MH]))) | 38 |

# | Web of Science Searches | |

|---|---|---|

1 | TS = (health services needs demand OR needs and demand, health services needs OR target population OR population OR target target populations OR health services need* OR need*, health services) AND TS = (sexual and reproductive health OR sexual health OR reproductive health OR reproductive health service* OR service*, reproductive health OR Family Planning Services OR Contraception OR Contraceptive Devices OR Contraceptive Agents OR family planning* OR contracept* OR condom* OR birth control OR steriliz* OR sterilis* OR vasectomy* OR women health OR women health service* OR service*, women health OR men’s health OR adolescent sexual health OR youth sexual health OR adolescent reproductive health OR youth reproductive health OR adolescent health OR youth health OR adolescent health services OR youth friendly services OR adolescent friendly services OR youth program* OR teenage* pregnancy) AND TS TS = (cortical deafness OR cortical deafness OR Deaf-Blind Disorders OR Hearing Loss, Bilateral OR acquired deafness OR hearing loss OR Deaf* OR acoustic handicap* OR acoustic disabili* OR acoustic disable* OR acoustic deficien* OR acoustic impair* OR acoustic loss* OR hearing handicap* OR hearing disabili* OR hearing disable* OR hearing deficien* OR hearing impair* OR hearing loss* OR hearing loss OR deafness OR acquired blindness OR blind* OR reduced vision OR low vision OR visual handicap* OR visual disabili* OR visual disable* OR visual deficien* OR visual impair* OR visual loss* OR vision handicap* OR vision disabili* OR vision disable* OR vision deficien* OR vision impair* OR vision loss* OR Blindness OR Disabled Persons | 5788 |

2 | ((TI = (“sexual health” OR “reproductive health”)) OR TI = (“sexual health” OR “reproductive health”)) AND #1 | 119 |

Appendix 2. Qualitative articles

Authors, year [number of reference] | Title | Sample/type of impairment | Country | Study design | Study aim | Main findings | Quality score* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Devine et al. [37] | “Freedom to go where I want”: improving access “Freedom to go where I want”: improving access to sexual and reproductive health for women with disabilities in the Philippines | Visual, Deaf and Mobility impairment | Philippines | Mixed-methods | (1) Increase understanding of the prevalence of disability; sexual and reproductive health experiences of women with disabilities; health service needs and experiences of women with disabilities; disability-related attitudes and practices of service providers and (2) Assess the effects of pilot interventions designed to increase demand for and supply of quality sexual and reproductive health supply of quality sexual and reproductive health and violence response services. | The Program W-DARE PAG intervention led to positive outcomes for women with disabilities including increased knowledge and access to SRH including protection from violence; improved social inclusion and participation in communities; enhance self-confidence and independence. The sustainability of these changes varied between individuals, and was influenced by factors such as individual capacity and agency; availability of resources including economic resources to support ongoing communication and connections with PAG participants; accessibility of communities; family responsibilities and support for social inclusion; and geographical location. | 13 out 21 |

Devkota et al. [38] | Healthcare provider’s attitudes towards disability and experience of women with disabilities in the use of maternal healthcare service in rural Nepal | Visual and Phisical Impairment | Nepal | Mixed-methods | This study is intended to fill this gap by conducting a mixed-method study that attempts to answer: what are the attitudes of healthcare providers towards disability? Are there any differences in attitudes between professional groups, their exposures to disability and their demographic characteristics (age, gender, etc.)? To provide further insight, we also asked service users about their experience regarding provider’s attitudes towards them. | Eighty-seven point six percent of the health care providers had been exposed to persons with disabilities, 58.8% had provided health care services to the mother, and 6.6% of the health care providers had received some disability-related training. The majority of women with disabilities perceived providers to have the negative attitude with poor knowledge, skills and preparation for providing care to persons with disabilities. Few participants perceived the providers as kind, respectful, caring or helpful. Many of the participants with disabilities said they avoided public hospitals and preferred to go to private institutions, even if it was costly. | 10 out 21 |

Badu et al. [51] | Enablers and barriers in accessing sexual and reproductive health services among visually impaired women in the Ashanti and Brong Ahafo Regions of Ghana | Visual Impairment | Ghana | Qualitative, interpretative | To explore the enablers for and barriers to accessing SRH services and care for visually impaired women in Ghana. | Financing costs of care, transportantion and Physical barriers were main barriers Preferential treatment was main enablers. | 13 out 21 |

Burke et al. [42] | A qualitative study to explore the barriers and enablers for young people with disabilities to access sexual and reproductive health services in Senegal | Phisical, Visual and Hearing Impairment | Senegal | Qualitative, interpretative | To understand whatn barriers and enablers young people with disabilities experience when accessing SRH services. Specific objectives were to explore: (1) the expressed needs and SRH vulnerabilities of young people with disabilities; and (2) their experiences of accessing SRH services, including the challenges faced in accessing these services. | Most participants never access SRH services. Less knowledge of modern contraceptive methods and lack of knowledge of where to obtain information by hearing impaired youth. Three main factors influencing where they would choose to access SRH: Confidentiality, anonymity, and proximity. Main barriers were provider attitudes and financial barriers. Men with visual impairments noted more internal barriers to seeking SRH services. People with hearing impairments, the communication barrier was especially pronounced, with reliance on family members to accompany them. All participants reported that they had to be accompanied by their family members to access health services. | 13 out 21 |

Gartrell et al. [52] | “We do not dare to love”: women with disabilities’ sexual and reproductive health and rights in rural Cambodia | Visual, Hearing and Physical | Cambodia | Qualitative, interpretative | To examine how intersectional discrimanations disadvantages shape women with disabilities’ sexual and reproductive health (SRH) experiences and asked whether women with disabilities face additional barriers than women without disabilities. | Women with disability experience the intersectionality of barriers related to gender norms and disability, and this reflect in their own perception of being unattractive or undesired. Women with hearing impairment borried about difficulties hearing their husband and preferred husbands with hearing impairments. Women with visual, hearing and developmental impairments considered themself less likely to marry. Sexual Reproductive Health Rights (SRHR) knowledge is low and done usually in informal conversations among family members, peers and neighbours. Marital status is key for SRHR knowledge. | 17 out 21 |

Gibson and Mykitiuk [41] | Health Care Access and Support for Disabled Women in Canada: Falling Short of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities: A Qualitative Study | Physical, sensory, cognitive, and/or psychiatric impairment. | Canada | Qualitative, interpretative | The study investigated two research questions: Are disabled Canadian women able to access the health services and supports they need? And, What limits or augments their ability to access these services and supports? By focusing on health care access in the lives of disabled women, we sought to identify practices, attitudes, and institutional arrangements that will enable women with disabilities to participate fully in society and realize the human rights they are guaranteed. | Participants described multiple intersecting factors that impeded or facilitated access to health care, both generic health services (e.g., family planning, screening tests such as mammograms or annual physicals) and impairment specific services. Participants experienced a number of barriers accessing professionals, support programs, and services. These are described under three broad themes: (1) Labyrinthine health service ‘systems,’ (2) assumptions, attitudes, and discriminatory practices, and (3) inadequate sexual health or reproductive services and supports. | 19 out 21 |

Devkota et al. [45] | Societal attitude and behaviours towards women with disabilities in rural Nepal: pregnancy, childbirth and motherhood | Physical and sensory disabilities | Nepal | Qualitative, interpretative | Share findings from a study that focused on public beliefs and attitudes towards disability in rural Nepal with particular reference to the experiences of women with disabilities around sexual and reproductive health, specifically during their pregnancy, childbirth and motherhood | The study found negative societal attitudes with misconceptions about disability based on negative stereotyping and a prejudiced social environment. Issues around the marriage of women with disabilities, their ability to conceive, give birth and safely raise a child were prime concerns identified by the non-disabled study participants. Many participants with and without disabilities reported anxieties and fears that a disabled woman’s impairment, would be transmitted to her baby. The pregnancy and childbirth of women with disabilities were often viewed as an additional burden for the family and society. Insufficient public knowledge about disability, stigma, stereotyping and prejudice among non-disabled people resulted to exclusion, discrimination and rejection of women with disabilities. | 16 out 21 |

Dean et al. [39] | You’re disabled, why did you have sex in the first place?’ An intersectional analysis of experiences of disabled women with regard to their sexual and reproductive health and rights in Gujarat State, India | Mobility, Visual, Deaf and Learning disability | India | Qualitative, interpretative | This paper explores the experiences of disabled women in relation to their SRH needs and rights in Gujarat, India from an intersectional perspective. By using an intersectional lens, this study explores the diversity as well as commonalities in women’s experiences | The majority of participants reported being aware of SRH services and perceive the need to use it services when something is wrong. Most consider valid to access SRH services as a married women and post-partum. All participants encountered assumptions about their sexuality and reproductive capacities by both family members and professionals. These assumptions were based on notions of their body as impaired, and reinforcing discourses that construct disabled women as non-sexual and, therefore, unable to fulfil the gendered role of a wife and mother. Although some participants challenged these discourses, their opportunities to effectively contest them in their own lives were shaped by intersecting power dynamics including: gender, type and severity of impairment, marital status, and socioeconomic status. | 20 out 21 |

Mprah, Anafi, and Addai Yeaboah [50] | Exploring misinformation of family planning practices and methods among deaf people in Ghana | Hearing Impairment | Ghana | Mixed-methods | To assess deaf people’s level of knowledge of pregnancy prevention methods and provides information on another component of the SRH needs of deaf people in Ghana, namely family planning, thus helping to provide more insights into the overall SRH needs of deaf people in Ghana. | There is a general lack of knowledge on pregnancy prevention methods. The study reveals a lack of knowledge on pregnancy prevention from young deaf people of both sexes. There is a dissenting view from the men participants about knowledge in family planning and pregnancy prevention, Also, there is a contracting view regarding risky sexual behaviour. However, there is a consensus about lack of knowledge with female participants. | 15 out 21 |

Tanabe et al. [43] | Intersecting Sexual and Reproductive Health and Disability in Humanitarian Settings: Risks, Needs, and Capacities of Refugees with Disabilities in Kenya, Nepal, and Uganda | Physical, intellectual, sensory, and mental impairments | Kenya, Nepal, and Uganda | Qualitative, interpretative | The study gathered information from refugee women, men, and adolescents aged 15–19 with physical, intellectual, sensory, and mental impairments in refugee settings in Kenya, Nepal, and Uganda | The refugees with disabilities demonstrated varying degrees of awareness around SRH, especially regarding the reproductive anatomy, family planning, and sexually transmitted infections. Lack of respect by providers was reported as the most hurtful by access. Pregnant women with disabilities were often discriminated against by providers and scolded by caregivers for becoming pregnant and bearing children; marital status was a large factor that determined if a pregnancy was accepted. Risks of sexual violence prevailed across sites, especially for persons with intellectual impairments | 17 out 21 |

Raut [60] | Case studies on sexual and reproductive health of disabled women in Nepal | Visual Impairment, Hearing Impairment, physical | Nepal | Qualitative, interpretative | Represent experience and the challenges disable women face in seeking sexual reproductive health information and services and their struggle to obtain rights | Disable women are deprived of their basic rights; the issue of sexual and reproductive health is not considered relevant for them; they face stigmas associated with marriage, sexual behavior and the use of contraceptives | 6 out 21 |

Mprah [29] | Knowledge and use of contraceptive methods amongst deaf people in Ghana | Hearing Impairment | Ghana | Qualitative, participatory | To investigate the level of knowledge and use of contraceptive methods amongst deaf people in Ghana with the aim of understanding their contraceptive behaviour and to improve access | Of the 13 methods shown in the survey, only three were known to about 70% of the adults and 60% of the students. This study found that whilst deaf people’s level of knowledge and use of contraceptives was generally low, contraceptive knowledge appeared to depend on the type of contraception, age and sex | 18 out 21 |

Mprah et al. [56] | Does disability matter? Disability in sexual and reproductive health policies and research in Ghana | Document analysis: Public policies about disability | Ghana | Qualitative, interpretative | The intent of this review is therefore to examine whether and how SRH policies and research have included issues on disability. The aim is to push for policy change to make the SRH concerns of persons with disabilities visible for action | Findings of the review indicated that while policies have been formulated to address SRH problems and research conducted to identify groups at high risk in Ghana, some of the policies and research have not given any attention to concerns of persons with disabilities. The review also found that in a few cases where attention is given, it is either often cursory or focused on the negative | 11 out 21 |

Mprah [55] | Perceptions about Barriers to Sexual and Reproductive Health Information and Services among Deaf People in Ghana | Hearing Impairment | Ghana | Qualitative, interpretative | To explore deaf people’s perceptions about challenges they encounter when accessing information and services on SRH issues | Barriers: communication, ignorance about deafness, attitudes towards deaf people, illiteracy among deaf people, privacy and confidentiality at SRH centres, limited time for consultation, and interpretation skills of sign language interpreters. Attitudes from health staff towards deaf people: Ignorance of deaf culture from health providers. Lack of privacy and confidentiality and they have to be accompanied by interpreter or family member enhance this perception | 15 out 21 |

Appendix 3. Observational articles

Authors, year [number of reference] | Title | Sample/types of impairment | Country | Study design | Study aim | Main findings | Quality score* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Hayes [54] | Availability of appropriately packaged information on sexual health for people who are legally blind | Nine rural Sexual Health Clinics in NSW as well as the major Sexual Health Clinics and Family Planning Centres in other states/VI | Australia | Observational, cross-sectional telephone-based survey | The purpose of this study was two-fold. To document what information on safe sex and STDs is available to people over the age of 18 who are legally blind and to discover whether such information is appropriately packaged, as in large print, braille, audio tape or computer disk to meet their specific needs. | In the different States, only agencies for the blind contain Braille or audio materials on sexuality issues, some of which are outdated. And most sexual health clinics in New South Wales and other States do not have alternative formats for accessing information. | 8 out of 34 |

Haynes et al. [33] | Contraceptive use at last intercourse among reproductive-aged women with disabilities: an analysis of population-based data from seven states | 8691 women aged 18–50 years/Vision; cognition; mobility; Self-care and Independent living | United States | Observational, cross-sectional, state-based telephone survey | To assess patterns of contraceptive use at last intercourse among women with physical or cognitive disabilities compared to women without disabilities. | Sexual activity prevalence among women with disabilities and without disabilities were similar (p = .79). 70% of women with disabilities and 74% of women without disabilities reported contraceptive use at last intercourse (p = .22) Among women using contraception, women with disabilities used male or female permanent contraception more often than women without disabilities (333 [29.6%] versus 1337 [23.1%], p < .05). | 16 out of 34 |

DeBeaudrap et al. [61] | Disability and Access to Sexual and Reproductive Health Services in Cameroon: A Mediation Analysis of the Role of Socioeconomic Factors | 620 youngs and adults/physical and/or sensory (visual and hearing) difficulties that occurred before the age of 10 years | Cameroon | Observational, cross-sectional, individual-based survey | This study aims to examine to what extent socioeconomic consequences of disability contribute to poorer access to sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services for Cameroonian with disabilities and how these outcomes vary with disabilities characteristics and gender | Disability was associated with deprivation for all socioeconomic factors assessed though significant variation with the nature and severity of the functional limitations was observed. Lower education level and restricted lifetime work mediated a large part of the association between disability and lower use of HIV testing and of family planning | 23 out of 34 |

Rivera Drew and Short [59] | Disability and Pap Smear Receipt Among U.S. Women, 2000 and 2005 | 9661 women aged 21–64/HI, VI, Cognitive and physical Impairments | United States | Observational, cross-sectional, National-based Survey | Seeks to broaden our understanding of the connection between disability and U.S. women’s receipt of Pap smears | Having a disability was negatively associated with Pap smear receipt (odds ratio, 0.6). Compared with women with no disabilities, those with mobility limitations and those with other types of limitations had reduced odds of having received a Pap smear (0.5–0.7). Disability was positively associated with having received a recommendation for a Pap smear (1.2); Among women who had not received a Pap smear, 31% of those with disabilities and 13% of others cited cost or lack of insurance as the primary reason | 26 out of 34 |

Shandra, Shameem, and Ghori [32] | Disability and the Context of Boys’ First Sexual Intercourse | 2737 young/VI, HI, Physical and chronic disabilities | United States | Observational, prospective cohort, individual-based survey | examines how adolescent disability associates with boys’ age of sexual debut, relationship at first sexual intercourse, degree of discussion about birth control before first sexual intercourse, and contraceptive use at first sexual intercourse | Compared to boys without disability, those with learning or emotional conditions are more likely and those with sensory conditions are less likely to report very early sexual debut. Boys with chronic illness are both more likely to have sex in a committed relationship and in an undefined relationship and also more likely to contracept at first intercourse. Those with sensory conditions are less likely to report very early sexual debut but are otherwise similar to boys without disability | 30 out of 34 |

Jamali [35] | Disability Measurement and Uptake of Sexual and Reproductive Health Services in Malawi | 5490 young, adults and elderly/PwD | England | Observational, Cross-sectional, household and individual based survey | The overarching goal of this study is to investigate the measurement of disability in Malawi and examine its relationship to SRH service utilisation | This study has found that there are significant variations in use of HIV counselling services by severity of functional disabilities, where women with severe functional disabilities are less likely to use HIV counselling services compared to those with no functional disabilities. The low use of HIV counselling service among women with severe functional disabilities implies that most women with functional disabilities are not aware of their HIV status | 14 out of 34 |

Dissanayake et al. [47] | Miscarriage Occurrence and Prevention Efforts by Disability Status and Type in the United States | 3843 women/Hearing Impairment, cognitive, mobility, selfcare disability and independent living disability | United States | Observational, cross-sectional, Observational Routinely-collected health Data based survey | The purpose of this study was to determine (1) whether occurrence of miscarriage differs by disability status and type; (2) whether women with disabilities are more likely to have recurrent miscarriages; and (3) what care, if any, women with disabilities have received to prevent miscarriage | Women with disabilities had higher odds of receiving services to prevent miscarriage compared with women without disabilities. Among women who received services, higher proportions of women with, vision, physical, or independent living disability received recommendations for bed rest (e.g., 65.007% of women with independent living disability versus 33.98% of women without disability, p = 0.018). | 20 out of 34 |

Yimer and Modiba [57] | Modern contraceptive methods knowledge and practice among blind and deaf women in Ethiopia. A cross-sectional survey | 326 blind and deaf women | Ethiopia | Observational, prospective cohort, individual-based survey | determine the knowledge and practice level on modern contraceptive methods among blind and deaf women about in Addis Ababa City, Ethiopia | The findings showed that nearly two third of the respondents were sexually active. The majority (97.2%) of study respondents had heard about FP methods, however the level of comprehensive knowledge on modern contraceptive methods was 32.5%. The prevalence of unwanted pregnancy was 67.0% and abortion was 44%. Almost half of sexually active respondents ever used modern contraceptive methods, yet the contraceptive prevalence at the time of survey was 31.1%. | 22 out of 34 |

Beyene, Munea, and Fekadu [40] | Modern Contraceptive Use and Associated Factors among Women with Disabilities in Gondar City, Amhara Region, North West Ethiopia: A Cross Sectional Study | 280 women with disabilities who had hearing, visual and limb defects (physical impairments) and who were living in Gondar city during the study period | Ethiopia | Observational, Cross-sectional, Community-based survey | To assess modern contraceptive use and associated factors among women with disabilities in Gondar city, Ethiopia | About 18% of participants had ever used modern contraceptive and the contraceptive prevalence rate among study participants and currently married women were 13.1% and 20.2% respectively. One fourth of respondents believed that existing family planning service delivery points were not accessible. | 17 out of 34 |

Mills [34] | Navigating sexual and reproductive health issues: Voices of deaf adolescents in a residential school in Ghana | 25 deaf adolescents, Junior High School student, aged 15–19 years, and willing to participate in the study | Ghana | Observational, prospective cohort, individual-based survey | The research questions are: (a) how do deaf adolescent students in the residential school apply information they have about sexual and reproductive health in their lives?; (b) what are their experiences regarding sexual and reproductive health?; and (c) what factors in their environment influence their sexual and reproductive health behaviors? | While some of the participants reported abstaining from sex, others disclosed that they had sexual experiences, consensual and non-consensual. Participants mentioned talking to teachers, peers, health professionals, parents and siblings about their SRH issues, but findings revealed challenges about communication with these groups of people in their social environment. | 11 out of 34 |

Horner-Johnson et al. [44] | Pregnancy among US women: differences by presence, type, and complexity of disability | 27567 women age 18-44/VI, HI, PwD, | United States | Observational, Cohort prospective, household and individual based survey | The purpose of this study was to describe the occurrence of pregnancy among women with various types of disability and with differing levels of disability complexity, compared to women without disabilities | Similar proportions of women with and without disabilities reported a pregnancy (10.8% vs. 12.3%, with 95% confidence intervals overlapping). Women with the most complex disabilities were less likely to have been pregnant, but women whose disabilities only affected basic actions did not differ significantly from women with no disabilities | 28 out of 34 |

Kelly and Kapperman [28] | Sexual Activity of Young Adults Who are Visually Impaired and the Need for Effective Sex Education | 9850 young adults/Visual Impairment | United States | Observational, cross-sectional, Observational Routinely-collected health Data based survey | The purpose of the study was to measure and compare the sexual behaviors of young adults aged 19 to 23 who were visually impaired with those of their peers who did not have specifically identified disabilities | 57% of the respondents with visual impairments and 65% of those without disabilities had sexual intercourse. 38% of the respondents with visual impairments versus 53% of those without disabilities reported having sexual intercourse during the three months before the survey. Respondents with visual impairments who reported using a condom was 64% compared with 54% of those without disabilities. Respondents with visual impairments reported using anything besides a condom to prevent pregnancy the last time they had sexual was 84% and those without disabilities 24% | 18 out of 34 |

Obasi et al. [58] | Sexual and reproductive health of adolescents in schools for people with disabilities | 357 Adolescents with disability/VI, HI, Intellectual disabilities | Ghana | Observational, prospective cohort, individual-based survey | This study sought to access the SRH services among adolescents with disabilities in four Special Needs Schools in Ghana | School teachers were the major source of information on SRH for the respondents (63.7%) followed by parents (12.2%). A majority (67.1%) of respondents had good knowledge of SRH. Factors which were significantly associated with knowledge level were age (p = 0.026), religion (p = 0.034), sources of information (p < 0.001), guardians (p = 0.049) | 17 out of 34 |

Heiman, Haynes and McKee [31] | Sexual Health Behaviors of Deaf American Sign Language (ASL) Users | 339 Deaf adults/HI | Not Applicable | Observational, prospective cohort, individual-based survey | We sought to characterize the self-reported sexual behaviors of Deaf individuals. | Deaf respondents were more likely than the general population respondents to self-report two or more sexual partners in the past year. HIV testing rates were similar between groups but lower for certain Deaf groups: Deaf women lower-income Deaf and among less educated Deaf than among respondents from corresponding general population groups | 27 out of 34 |

Kassa et al. [30] | Sexuality and Sexual Reproductive Health of Disabled Young People in Ethiopia | 426 disabled youth aged 10 to 24 years/VI, HI, Mobility Impairment | Ethiopia | Observational, prospective cohort, individual-based survey | We aimed to assess the SRH status and associated factors among 426 YPWD in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia | 75% started sex between 15 and 19 years. Only 35% had used contraceptive during their first sexual encounter. 59% of the sexually experienced YPWD had multiple lifetime sexual partners. Only 48% consistently used condoms with their casual or commercial sexual partners. 24% had a history of sexually transmitted infections | 23 out of 34 |

De Beaudrap et al. [46] | HandiVIH—A population-based survey to understand the vulnerability of people with disabilities to HIV and other sexual and reproductive health problems in Cameroon: protocol and methodological considerations | 850 youngs 15–49/VI, HI | Cameroon | Observational, prospective cohort, individual-based survey | This study aims at improving our understanding of the situation of people with disabilities in Sub-Saharan Africa in relation to HIV and their SRH. The primary objectives of this study are to compare quantitatively the risk of HIV infection among people with disabilities | Not applicable | 21 out of 34 |

Appendix 4. Reviews studies

Authors, year [number of reference] | Title | Type of review | Sample/type of impairment | Study aim | Main findings | Quality score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Groce et al. [27] | HIV issues and people with disabilities: A review and agenda for research | Narrative review | PwD | Summarise what is currently known about the intersection between HIV and AIDS and disability, paying particular attention to the small but emerging body of epidemiology data on the prevalence of HIV for people with disabilities, as well as the increasing understanding of HIV risk factors for people with disabilities | While there is a growing body of work investigating HIV as it affects people with disabilities, there remain numerous and conspicuous gaps in our knowledge. Studies have clearly established the fact that the level of HIV knowledge for people with disabilities is generally low. Some studies have investigated the prevalence of unsafe sex and other risk factors, but significant gaps exist exploring the various risk factors for HIV across different disability groups. If reviewed by type of impairment, evidence from the studies shows that persons with mental health disabilities and hearing impairments are at equal risk as the general population for becoming infected | 10 out of 12 |

Rodriguez Dominguez and Mendoza Diaz [61] | Anticoncepción postcoital en mujeres adultas y adolescentes sordas | Narrative review | HI | Updated information on the procedures used in postcoital contraception, either through the use of hormonal (contraceptive tablets) or non-hormonal (intrauterine devices) methods, is reviewed, with the aim of ensuring that the deaf female population of fertile age are aware and able to use these methods | There is no specification for deaf women | 1 out of 12 |

Kaplan [43] | Special Issues in Contraception: Caring for Women With Disabilities | Narrative review | PwD | Focus on contraceptive care for women with disabilities including movement limitations, sensory impairments, seizure disorders, developmental, disability, and emotional and psychiatric disorders | There are specific considerations for the use of different contraceptive methods in women with disabilities. There is the need of a welcoming environment as well as clinical expertise in specific issues related to the population | 8 out of 12 |

Carew et al. [36] | The sexual lives of people with disabilities within low- and middle-income countries: a scoping study of studies published in English | Scoping review | PwD | Provide a scoping review on sexuality and disability in LMICs | May engage in risky sexual behaviours and posses low level of knowledge about SRH and safe sex practices. PwD families and close communities are reluctant to accept PWD are sexual beings. PWD experience several barriers to access SRH services PWD have barriers accessing sexual education | 15 out 27 |

Schindeler and Aldersey [48] | Community-Based Rehabilitation Programming for Sex(uality), Sexual Abuse Prevention, and Sexual and Reproductive Health: A Scoping Review | Scoping review | PwD | The aim of this scoping review was to explore the literature that discussed CBR programming on the topics of sex(uality), sexual abuse prevention, and SRH for children and adults with disabilities in LMICs | Fifteen studies were identified. The majority were implemented in Africa; targeted all people with disabilities, regardless of gender, age, or type of disability; and frequently focussed on the topic of HIV/AIDS. The interventions were most commonly designed to educate people with disabilities on issues of sex(uality), sexual abuse prevention, or SRH | 21 out of 27 |

Brown et al. [49] | Identifying reproductive-aged women with physical and sensory disabilities in administrative health data: A systematic review | Systematic Review | PwD | To identify and appraise literature on the development and validation of algorithms to identify reproductive-aged women with physical disabilities and sensory disabilities in administrative health data | In the included studies only found 2 unique algorithm aimed to correlate diagnoses, procedure codes, and prescriptions with ability to access routine care as an indicator of functional limitation. The other algorithm used diagnostic and procedure codes to identify use of mobility-assistive devices to measure functional limitation. Only one algorithm was validated against self-reported disability | 22 out 27 |

Hameed et al. [53] | From words to actions: systematic review of interventions to promote sexual and reproductive health of persons with disabilities in low- and middle-income countries | Systematic Review | PwD | The aim of this scopin This systematic review examines the following two questions: (1) what, if any, interventions are currently in place to promote sexual and reproductive health and rights of persons with disabilities in low- to middle-income countries? and (2) how effective are they?g review was to explore the literature that discussed CBR programming on the topics of sex(uality), sexual abuse prevention, and SRH for children and adults with disabilities in LMICs | 11 interventions were from upper middle income settings; two from lower-income settings; only one operated in rural areas. Interventions addressed intellectual impairment (6), visual impairment (6), hearing impairment (4), mental health conditions (2) and physical impairments (2). Most interventions (15/16) focus on information provision and awareness raising. We could not identify any intervention promoting access to maternal health, family planning and contraception, or safe abortion for people with disabilities | 22 out of 27 |

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Besoain-Saldaña, A., Bustamante-Bravo, J., Rebolledo Sanhueza, J. et al. Experiences, Barriers, and Facilitators to Sexual and Reproductive Health Care Access of People with Sensory Impairments: A Scoping Review. Sex Disabil 41, 411–449 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-023-09778-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-023-09778-y