Abstract

Are smaller firms more productive? Intuitively, while small firms have the advantage of more flexible management and lower response time to market changes, larger firms have the advantages of economies of scale, political clout and better access to government credits, contracts and licenses, particularly in developing countries. Using a panel dataset from a commercially available database of financial statements of manufacturing firms in India, we find that firms in the lowest quintile of the asset distribution that invest in research and have better liquidity are most productive. The Indian manufacturing sector, characterized by both large scale public and private firms as well as numerous smaller firms, provides an ideal setting. Our findings are robust to alternative definitions of size, alternative estimation methods and alternative estimates of total factor productivity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Though it is more usual to estimate productivity at the plant level, firm-level productivity is more appropriate in our context as size-restriction is imposed at the firm-level and not the plant-level. Admittedly, they are not identical as a firm may have several plants, and as Winter (1999) shows firm financials may affect plant productivity. Using balance sheet data is a more modern trend, partly because of availability of such databases. One example is Khandelwal and Topalova (2010), who use the same database to estimate TFP.

The unorganized sector accounts for about 45 % of the employment in the manufacturing sector and contributes to about 44 % of the GDP as estimated by the Central Statistical Organisation, India. The data we use does include firms which are not publicly traded. A detail discussion of the informal manufacturing sector in India is beyond the scope of this paper.

Source: Development Commission (SSI), Third Census, Government of India.

Morris and Basant (2006) present a detailed discussion of the financial constraints faced by small firms in India.

We use one more source of data for robustness checks. There is some evidence that large firms pay higher wages (Idson and Oi [1999], Brown and Medoff [1989]). If this is systematically the case, then our calculation of labor is biased, as we use an industry-wide deflator. This will underestimate the TFP of larger firms affecting our regression results. Since firm-level wage data is missing for a large majority of firms, we cannot deal with this directly as it will lead to a drastic loss of sample size. Therefore, we deal with this in a couple of indirect ways. First, we see if, given the limited data, there is any evidence that large firms systematically pay more. We do not find such evidence. We next look at a roughly comparable database on the Indian manufacturing sector, the Annual Survey of Industries, and estimate the average wage premium between small and large firms (Chamarbagwala and Sharma [2012]). The average wage rate of firms in the fifth quintile is approximately three times that in the first quintile. That is, large firms pay almost three times the wage an average small firm pays. We recalibrate our wages to account for this wage premium and then recalculate labor and TFP. On estimating our various specifications, we find that the small firms still have significantly higher TFP than the larger firms, though the coefficients become smaller. The details of these exercises are available upon request.

Please refer to Van Beveren (2012) for a detailed discussion on the various measures of TFP.

For brevity, we exclude the details of TFP estimations. The authors will be happy to make them available upon request.

We also use a more popular definition of size, as discussed above—size by quintiles of employment. As mentioned in the data section, we do not have data on employment and impute the same by dividing the wage bill by average wage rate. The imputed employment is then divided into quintiles by year and by industry. We once again find a positive and significant relation between being small by this definition and being productive. However, as this imputation of labor is an imprecise method of measuring employment, we relegate it to the “Appendix”.

We obtain similar results when we define size in terms of quintiles of market share instead of assets. This is expected, as asset-based measure of size and sales-based measure of size are likely to be very similar. These results are available upon request from the authors.

References

Ackerberg, D. A., Caves, K., & Frazer, G. (2006). Structural identification of production functions. Los Angeles: UCLA Department of Economics.

Acs, Z. J., & Audretsch, D. B. (1987). Innovation, market structure, and firm size. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 69(4), 567–574.

Acs, Z. J., & Audretsch, D. B. (1990). Innovation and small firms. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Arellano, M., & Bond, S. (1991). Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. The Review of Economic Studies, 58(2), 277–297.

Arellano, M., & Bover, O. (1995). Another look at the instrumental variable estimation of error-components models. Journal of Econometrics, 68(1), 29–51.

Aw, B. Y. (2002). Productivity dynamics of small and medium enterprises in Taiwan. Small Business Economics, 18(1), 69–84.

Aw, B. Y., Chen, X., & Roberts, M. J. (2001). Firm-level evidence on productivity differentials and turnover in Taiwanese manufacturing. Journal of Development Economics, 66(1), 51–86.

Baily, M. N., Bartelsman, E. J., & Haltiwanger, J. (1996). Downsizing and productivity growth: Myth or reality? Small Business Economics, 8(4), 259–278.

Beck, T., Demirgüç-Kunt, A., & Maksimovic, V. (2005). Financial and legal constraints to growth: Does firm size matter? The Journal of Finance, 60(1), 137–177.

Bernard, A. B., Eaton, J., Jensen, J. B., & Kortum, S. (2003). Plants and productivity in international trade. The American Economic Review, 93(4), 1268–1290.

Bigsten, A., & Gebreeyesus, M. (2007). The small, the young, and the productive: Determinants of manufacturing firm growth in Ethiopia. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 55, 813–840.

Blalock, G., & Gertler, P. J. (2009). How firm capabilities affect who benefits from foreign technology. Journal of Development Economics, 90(2), 192–199.

Blundell, R., & Bond, S. (1998). Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Econometrics, 87(1), 115–143.

Bound, J., Cummins, C., Griliches, Z., Hall, B. H., & Jaffe, A. B. (1982). Who does R&D and who patents? NBER working paper.Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Brown, C., & Medoff, J. (1989). The employer size-wage effect. The Journal of Political Economy, 97(5), 1027–1059.

Chamarbagwala, R., & Sharma, G. (2011). Industrial de-licensing, trade liberalization, and skill upgrading in India. Journal of Development Economics, 96(2), 314–336.

Claessens, S., Djankov, S., & Lang, L. H. P. (2000). The separation of ownership and control in East Asian corporations. Journal of Financial Economics, 58(1–2), 81–112.

Cohen, W. M., & Klepper, S. (1996). A reprise of size and R and D. The Economic Journal, 106(437), 925–951.

Dhawan, R. (2001). Firm size and productivity differential: Theory and evidence from a panel of US firms. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 44(3), 269–293.

Fernandes, A. M. (2003). Trade policy, trade volumes, and plant-level productivity in Colombian manufacturing industries. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Hall, R. E., & Jones, C. I. (1999). Why do some countries produce so much more output per worker than others? The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114(1), 83–116.

Hausman, J. A., Hall, B., & Griliches, Z. (1984). Econometric models for count data with an application to the patents-R&D relationship. Econometrica, 52(4), 909–938.

Henderson, R. (1993). Underinvestment and incompetence as responses to radical innovation: Evidence from the photolithographic alignment equipment industry. The Rand Journal of Economics, 24(2), 248–270.

Hsieh, C.-T., & Klenow, P. (2012). The life cycle of plants in India and Mexico. Working paper 18133. UK: DFID.

Idson, T. L., & Oi, W. Y. (1999). Workers are more productive in large firms. American Economic Review, 89(2), 104–108.

Jovanovic, B. (1982). Selection and the evolution of industry. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society, 50(3), 649–670.

Khandelwal, A., & Topalova, P. (2011). Trade liberalization and firm productivity: The case of India. Review of Economics and Statistics, 93(3), 995–1009.

Kim, J., Lee, S. J., & Marschke, G. (2009). Relation of firm size to R&D productivity. International Journal of Business, 8(1), 7–19.

Klenow, P. J., & Rodriguez-Clare, A. (1997). The neoclassical revival in growth economics: Has it gone too far? In B. Bernanke & G. Rotemberg (Eds.), NBER macroeconomics annual 1997 (pp. 73–102). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Levinsohn, J., & Petrin, A. (2003). Estimating production functions using inputs to control for unobservables. Review of Economic Studies, 70(2), 317–341.

Mazumdar, D. (2009). A comparative study of the size structure of manufacturing in Asian countries. Manila: Asian Development Bank (processed).

Melitz, M. J. (2003). The impact of trade on intra-industry reallocations and aggregate industry productivity. Econometrica, 71(6), 1695–1725.

Ministry of Law and Justice, Government of India. (2006). The Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises Development Act, 2006.

Morris, S., & Basant, R. (2006). Small-scale industries in the age of liberalization, INRM Policy Brief No. 11: Asian Development Bank.

Nagaraj, P. (2012). Essays on firm behavior. Order No. 3525915. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses, 105, City University of New York. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.gc.cuny.edu/login?

Roodman, D. (2006). How to do xtabond2. Paper presented at the North American Stata Users’ Group Meetings 2006, Boston, MA.

Scherer, F. M. (1986). Innovation and growth: Schumpeterian perspectives (Vol. 1). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Shefer, D., & Frenkel, A. (2005). R&D, firm size and innovation: An empirical analysis. Technovation, 25(1), 25–32.

Syrneonidis, G. (1996). Innovation, firm size and market structure: Schumpeterian hypotheses and some new themes. OECD Economic Studies, 27, 35–70.

Syverson, C. (2011). What determines productivity? Journal of Economic Literature, American Economic Association, 49(2), 326–365.

Tybout, J. R. (2000). Manufacturing firms in developing countries: How well do they do, and why? Journal of Economic Literature, 38(1), 11–44.

Van Beveren, I. (2012). Total factor productivity estimation: A practical review. Journal of Economic Surveys, 26(1), 98–128.

Van Biesebroeck, J. (2005). Firm size matters: Growth and productivity growth in African manufacturing. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 53, 545–583.

Williamson, O. E. (1967). Hierarchical control and optimum firm size. The Journal of Political Economy, 75(2), 123–138.

Winter, J. K. (1999). Does firms’ financial status affect plant-level investment and exit decisions? Publications 98-48, University of Mannheim.

Wooldridge, J. M. (2009). On estimating firm-level production functions using proxy variables to control for unobservables. Economics Letters, 104(3), 112–114.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Sangeeta Pratap, Jonathan Conning, Russell Green, and seminar participants at the New York State Economic Association Annual Meeting, The City College of New York and North American Productivity Workshop (NAPW), 2012 for comments and suggestions; and Institute for Study of Industrial Development, New Delhi, India for their support with the data. Gunjan Sharma also gracefully provided data. Support for this project was provided by a PSC-CUNY Award, jointly funded by The Professional Staff Congress and The City University of New York. Priya Nagaraj acknowledges financial support from the Graduate Center, CUNY and NAPW.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: construction of variables from the PROWESS database

Appendix: construction of variables from the PROWESS database

1.1 Output

Output is deflated sales adjusted for change in inventory and purchase of finished goods. In PROWESS, purchase of finished goods is defined as finished goods purchased from other manufacturers purely for resale purpose. It therefore needs to be subtracted from sales to arrive at the firms’ manufactured output. An increase in inventory is added to sales to arrive at output and a decrease subtracted.

1.2 Value added and input

Value added is defined as the difference between output and inputs. The variable input is defined as the sum of material, fuel, packaging and distribution expenses. Value added is used in the calculation of TFP.

1.3 Total factor productivity (TFP)

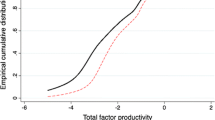

TFP is calculated by the Levinsohn–Petrin method that uses material as the proxy variable. Both labor and fuel are considered as freely varying inputs. TFP has been calculated using both output and value added as the dependent variable.

1.4 Labor employment

Labor is calculated by dividing the compensation to employees by emoluments per employee. Emoluments per employee are the all industry average emoluments per employee as given by the Central Statistical Organization (CSO). CSO is a part of the Ministry of Statistics and Planning of the Government of India.

1.5 Capital stock

Capital stock has been constructed by adding current period investment to last period’s capital stock net of depreciation. Capital has been depreciated at the rate of 10 %.

1.6 Ownership

PROWESS defines ownership broadly as Government owned (either Central or State), private sector owned, cooperative sector and joint sector. The private sector comprises Indian private sector and foreign private sector. Both Indian and foreign private sector are further divided into Private (Indian/foreign) and Business groups (Indian/foreign). We have combined the last two categories, Indian business groups and foreign business houses into one indicator for ownership by a large business group. The variable takes unit value if the firm is owned by a large Indian business group or by a foreign business house and zero otherwise. The category, foreign business houses, includes NRI business houses like the Hinduja group and the Ispat (Mittal) group. Indicator for Export participation: The indicator for export participation takes the value 1 when value of exports for the year exceeds zero. The value of exports is the sum of exports of goods and services.

1.7 Classification of NIC-2 digit industry

Prowess gives the National Industrial Classification (NIC) of the firms in it dataset. NIC classification is consistent with the ISIC rev.3. The classification in some cases is only two digits while in others it is 5-digits. We have therefore maintained a 2-digit classification. The dataset saves this classification in text format and not as number. As a consequence, some of the classifications are incorrect as the zero is missing. On careful examination of the company name and economic activity I found 19 such codes which were to be preceded by a zero. The NIC codes were then converted to 2-digit.

1.8 Research and development

This refers to the firm’s expenditure on research and development as a proportion of sales. The expenditure on research and development includes expenditure on royalties, technical know how and license fees other than expenses on research and development activities. Fewer small firms, around 9 %, spend on R&D activities as compared to around 63 % of the largest firms (the fifth quintile). However, small firms spend a larger proportion of their sales on research than the largest firms (2.86 % as compared to 1.14 % by the largest).

1.9 Cash flow

Cash flow is total cash in hand plus cash in bank as reported in the balance sheet.

1.10 Classification of industry as manufacturing

PROWESS classifies the firms as manufacturing or non-manufacturing. Careful examination showed five NIC codes which had been wrongly coded as non-manufacturing. We have changed those to manufacturing maintaining conformity to ISIC rev3. There are some firms who purchase more finished goods than sell. The variable purchase of finished goods is greater than sales. These firms have been classified as manufacturing though they seem to be traders. We have classified these as non-manufacturing and therefore they have been removed from the dataset.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

De, P.K., Nagaraj, P. Productivity and firm size in India. Small Bus Econ 42, 891–907 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-013-9504-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-013-9504-x