Abstract

While Buchanan is best known for the economics of politics and constitutions, his seminal contributions to this field are but one branch of his more underlying methodology and approach to doing social science. Buchanan’s fundamental project was to re-orient economics and social science toward an analysis of symbiotic exchange (catallactics) rather than of antiseptic allocation (optimization). The most definite statement of this contribution lies in Buchanan’s 1963 presidential address to the Southern Economic Association, “What should economists do?” which was later expanded into a book of the same title. This paper seeks to draw attention to several of Buchanan’s more recent but lesser known articles where he fully develops this theme. He calls on economists to rediscover Adam Smith’s “elementary notion” about the division of labor and the extent of the market, and he professes the notion of “generalized increasing returns” as a mechanism for economists to rediscover their Scottish Enlightenment roots within the neoclassical framework. In this same vein, we also discuss how Buchanan’s rediscovery might apply to two prominent and ongoing twenty-first century issues, trade restrictions and populism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Source (video): “Daring to Be Different: Reflections on the Life and Work of James Buchanan”, GMU Archives.

Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences press release, October 16, 1986, at www.nobelprize.org.

Buchanan repeats a similar response in other places. For example, a few years earlier, in his 1979 essay “Politics without Romance”, he called public choice a “new… sub-discipline that falls halfway between economics and political science…. Public choice theory essentially takes the tools and analysis that have been developed to quite sophisticated analytical levels in economic theory and applies these tools and methods to the political or government sector, to politics, to the public economy” (Buchanan 1996[1999], pp.46–48).

Note that even if Boettke, Fink and Smith locate John Hicks in the mainstream groups, Hicks himself seems to have changed his position later in life: “In my sub-title, and in the text of Chapter I, I have proclaimed the ‘Austrian’ affiliation of my ideas; the tribute to Böhm-Bawerk, and to his followers, is a tribute that I am proud to make. I am writing in their tradition; yet I have realized, as my work continued, that it is a wider and bigger tradition than at first appeared. The ‘Austrians’ were not a peculiar sect, out of the main stream; they [?] were in the main stream; it was the others who were out of it” (Hicks 1973, p. 12, n. 1).

For excellent papers that trace Buchanan’s methodology to his SEA presidential speech, see Shughart and Thomas (2014), Wagner (2017) and Boettke and Candela (2017). For details concerning the reception and diffusion of Robbins’s definition of economics during the twentieth century, see Backhouse and Medema (2009).

Buchanan does not claim that economists entirely abandoned Smithean questions. In each of the works discussed here (Buchanan 1964, Buchanan and Yoon 1994, 1999, 2000), we find pointers to isolated works along the way that failed to influence the practitioners of economics and instead became mere fixtures in the history of thought. For excellent work tracing the lineage of Buchanan’s thought from pre-Enlightenment philosophers through his twentieth century adversaries, see Leighton and Lopez (2013), Shughart and Thomas (2014), and Boettke and Candela (2017).

Kirzner (1965, p. 257) replies by arguing that Buchanan’s concern has been raised for years by a “group of writers” and that, while agreeing with Buchanan, computational problems still are part of the economic problem (even if not the main subject of study).

See Pennington’s (2011) discussion of robust political economy.

This is, for instance, the approach taken by García Hamilton (1998) with respect to Latin America’s propemsity for authoritarian governments and low levels of productivity.

References

Abts, K., & Rummens, S. (2007). Populism versus democracy. Political Studies,55(2), 405–424.

Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2012). Why nations fail: The origins of power, prosperity and poverty. New York: Crown Publishers.

Backhouse, R. E., & Medema, S. G. (2009). Defining economics: The long road to acceptance of the Robbins definition. Economica,76, 805–820.

Baldwin, R. E., & Magee, C. S. (2000). Is trade for sale? Congressional voting on recent trade bills. Public Choice,105, 79–101.

Besley, T. (2006). Principal agents? The political economy of good government. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Boaz, D. (2013). James M. Buchanan, RIP. https://www.cato.org/blog/james-m-buchanan-rip. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

Boettke, P. J. (1997). Where did economics go wrong? Modern economics as a flight from reality. Critical Review,11(1), 11–64.

Boettke, P. J., & Candela, R. (2017). The liberty of progress: Increasing returns, institutions, and entrepreneurship. Social Philosophy and Policy,34(2), 136–163.

Boettke, P. J., Fink, A., & Smith, D. J. (2012). The impact of Nobel Prize winners in economics: Mainline vs. mainstream. American Journal of Economics and Sociology,71(5), 1219–1249.

Boettke, P. J., Coyne, C. J., & Newman, P. (2016). The History of a Tradition: Austrian Economics from 1871 to 2016. Research in the History ofEconomic Thought and Methodology, 34A, 199–243.

Boettke, P. J., & Lopez, E. J. (2002). Austrian and public choice economics: On common ground. The Review of Austrian Economics,15(2/3), 111–119.

Buchanan, J. M. (1949). The pure theory of government finance: A suggested approach. The Journal of Political Economy,57(6), 496–505.

Buchanan, J. M. (1963[1999]). The Collected Works of James M. Buchanan. Volume 6. Cost and Choice (Vol. 6). Indianapolis: Liberty Fund.

Buchanan, J. M. (1964). What should economists do? Southern Economic Journal,30(3), 213–222.

Buchanan, J. M. (1975 [2000]). The collected works of James M. Buchanan. Volume 7. The limits of liberty. Indianapolis: Liberty Fund.

Buchanan, J. M. (1996 [1999]). Politics without romance: A sketch of positive public choice theory and its normative implications. In J. M. Buchanan & R. D. Tollison (Eds.), The theory of Public Choice II. The University of Michigan Press.

Buchanan, J. M., & Brennan, G. (1980 [2000]). The collected works of James M. Buchanan. Volume 9. The power to tax. Indianapolis: Liberty Fund.

Buchanan, J. M., & Brennan, G. (1985 [2000]). The collected works of James M. Buchanan. Volume 10. The reason of rules. Indianapolis: Liberty Fund.

Buchanan, J. M., & Congleton, R. D. (2006). Politics by principle, not by interest. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Buchanan, J. M., & Tullock, G. (1962 [1999]). The collected works of James M. Buchanan. Volume 3. The calculus of consent. Indianapolis: Liberty Fund.

Buchanan, J. M., & Vanberg, V. J. (2002). Constitutional implications of radical subjectivism. The Review of Austrian Economics, 15, 121–129. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015754302238

Buchanan, J. M., & Wagner, R. E. (1977 [2000]). The collected works of James M. Buchanan. Volume 8. Democracy in Deficit. Indianapolis: Liberty Fund.

Buchanan, J. M., & Yoon, Y. J. (1994). The return of increasing returns. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Buchanan, J. M., & Yoon, Y. J. (1999). Generalized increasing returns, Euler’s theorem, and competitive equilibrium. History of Political Economy,31(3), 511–523.

Buchanan, J. M., & Yoon, Y. J. (2000). A smithean perpective on increasing returns. Journal of the History of Economic Thought,22(1), 43–48.

Cachanosky, J. C. (1985). La ciencia económica vs. la economía matemática (I). Libertas,3(octubre), 1–3.

Cachanosky, J. C. (1986). La ciencia económica vs. la economía matemática (II). Libertas, mayo.

Cachanosky, N., & Padilla, A. (2019). Latin american populism in the 21st century. The Independent Review,24(2), 209–266.

Cachanosky, N., & Padilla, A. (2020). A panel data analysis of Latin American populism. Constitutional Political Economy. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10602-020-09302-w.

Chesterley, N., & Roberti, P. (2016). Populism and institutional capture. Working Paper DSE No. 1086. Bologna: University di Bologna.

Cowen, T. (2013). A few James Buchanan reminiscences. Retrieved from https://marginalrevolution.com/marginalrevolution/2013/01/a-few-james-buchanan-reminiscences.html.

de la Torre, C. (2016). Populism and the politics of the extraordinary in Latin America. Journal of Political Ideologies,21(2), 121–139.

Doherty, B. (2013). Nobel Prize winning economist James Buchanan, R.I.P. https://reason.com/2013/01/09/nobel-prize-winning-economist-james-buch/. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

Dornbusch, R., & Edwards, S. (1990). Macroeconomic populism. Journal of Development Economics,32(2), 247–277.

Edwards, S. (2010). Left behind: Latin America and the false promise of populism. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Eusepi, G., & Wagner, R. E. (2017). Public debt: An illusion of democratic political economy. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Gallo, E. L. (1987). La tradición del orden social espontáneo: Adam Ferguson. David Hume y Adam Smith. Libertas,6(mayo), 131–153.

García Hamilton, J. I. (1998). El autoritarismo y la improductividad en hispanoamérica. Sudamericana.

Grier, K., & Maynard, N. (2016). The economic consequences of Hugo Chavez: A synthetic control analysis. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization,125, 1–21.

Groseclose, T. (2013). Nobel economist James M. Buchanan, 1919–2013. Retrieved from https://ricochet.com/177970/archives/nobel-economist-james-m-buchanan-1919-2013/.

Grossman, M., & Helpman, E. (1994). Protection for sale. The American Economic Review,84(4), 833–850.

Guiso, L., Herrera, H., Morelli, M., & Sonno, T. (2017). Demand and supply of populism. EIEF working paper no. 17/03. Roma: Einaudo Institute for Economics and Finance.

Hawkins, K. A. (2003). Populism in Venezuela: The rise of Chavismo. Third World Quarterly,24(6), 1137–1160.

Hayek, F. A. (1967 [1978]). Studies in philosophy, politics and economics. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Hicks, J. R. (1973). Capital and time. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Higgs, R. (2013). James M. Buchanan (October 3, 1919–January 9, 2013). https://blog.independent.org/2013/01/09/james-m-buchanan-october-3-1919-january-9-2013/. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

Holcombe, R. G. (2013). James M. Buchanan: 1919–2013. https://blog.independent.org/2013/01/09/james-m-buchanan-1919-2013/. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

Horwitz, S. G. (2013). RIP: James M. Buchanan (1919–2013). http://bleedingheartlibertarians.com/2013/01/rip-james-m-buchanan-1919-2013/. Retrieved 10 July 2019

Kirzner, I. M. (1965). What economists do. Southern Economic Journal,31(3), 257–261.

Kohn, M. (2004). Value and exchange. Cato Journal,24(3), 303–339.

Kuhn, T. S. (1962 [1996]). The structure of scientific revolutions. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press.

Leeson, P. T. (2007). Trading with bandits. Journal of Law and Economics,50(2), 303–321.

Leeson, P. T. (2014). Anarchy unbound: Why self-governance works better than you think. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Leighton, W. A., & Lopez, E. J. (2013). Madmen, intellectuals, and academic scribblers: The economic engine of political change. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press.

Lekachman, R. (1986). A controversial Nobel choice?; Turning into these conservative times. The New York Times1. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/1986/10/26/business/business-forum-controversial-nobel-choice-turning-these-conservative-times.html.

Lopez, E. J. (2010). The pursuit of justice: Law and economics of legal institutions. New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

Magee, C. S., Brock, W., & Young, L. (1989). Black hole tariffs and endogenous policy theory: Political economy in general equilibrium. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Martin, A. (2020). The subjectivist-contrarian position. Public Choice. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-020-00808-3.

Matthews, D. (2013). RIP James Buchanan: The man who got economists to care about politics. The Washington Post Wonk Blog. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2013/01/09/rip-james-buchanan-the-man-who-got-economists-to-care-about-politics/?arc404=true.

Mazzuca, S. L. (2013). The rise of rentier populism. Journal of Democracy,24(2), 108–122.

McFadden, D. (1979). A note on the computability of tests of the strong axiom of revealed preference. Journal of Mathematical Economics, 6(1), 15–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4068(79)90020-X.

Mueller, D. (2003). Public choice III. Cambridge: Cambrdige University Press.

Ocampo, E. (2015). Entrampados en la farsa: El populismo y la decadencia argentina. Buenos Airers: Claridad.

Olson, M. (2000). Power and prosperity. New York: Basic Books.

Payne, J. L. (2002). Explaining the persistent growth in tax complexity. In D. P. Racheter & R. E. Wagner (Eds.), Politics, taxation, and the rule of law (pp. 167–184). Boston, MA: Springer.

Pennington, M. (2011). Robust political economy: Classical liberalism and the future of public policy. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Pesendorfer, W. (1995). Design innovation and fashion cycles. American Economic Review,85, 771–792.

Podemska-Mikluch, M., & Wagner, R. E. (2013). Dyads, triads, and the theory of exchange: Between liberty and coercion. The Review of Austrian Economics,26(2), 171–182.

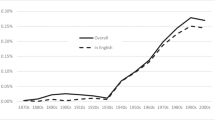

Reksulak, M., Shughart, W. F., II, & Tollison, R. D. (2004). Economics and english: Language growth in economic perspective. Southern Economic Journal,71(2), 232–259.

Riker, W. H. (1988). Liberalism against populism: A confrontation between the theory of democracy and the theory of social choice. Long Grove: Waveland Pr Inc.

Rizzo, M. J. (2013). James M. Buchanan: A preliminary appreciation. https://thinkmarkets.wordpress.com/2013/01/09/james-m-buchanan-a-preliminary-appreciation/. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

Rode, M., & Revuelta, J. (2015). The wild bunch! An empirical note on populism and economic institutions. Economics of Governance,16(1), 73–96.

Rodrik, D. (1995). Political economy of trade policy. Handbook of international economics,3, 1457–1494.

Rodrik, D. (2018). Is populism necessarily bad economics? AEA Papers and Proceedings,108, 196–199.

Rowan, H. (1986). Discreetly Lifted Eyebrows over Buchanan’s Nobel. The Washington Post1.

Rowley, C. K., & Schneider, F. (Eds.). (2003). The encyclopedia of public choice. New York: Springer.

Seaberry, J. (1986). Nobel winner sees economics as common sense; Buchanan says his public choice helps explain political actions. The Washington Post.

Shughart, W. F., II, & Thomas, D. W. (2014). What did economists do? Evolutionary, voluntary, and coercive institutions for collective action. Southern Economic Jounal,80(4), 926–937.

Smith, V. L. (2002). Constructivist and ecological rationality in economics. In Nobel memorial lecture.

Stearns, M., & Zywicki, T. (2019). Public choice concepts and applications in law. Eagan: West Publishing.

Stringham, E. P. (2015). Private governance: Creating order in economic and social life. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Tollison, R. D. (2013). James M. Buchanan: In memoriam. Southern Economic Journal,80(1), 1–4.

Tullock, G. (1967). The welfare costs of tariffs, monopolies, and theft. Economic Inquiry,5(3), 224–232.

Vanberg, G. (2017). Consitutional political economy, democratic theory, and institutional design. Public Choice,177, 199–216.

von Mises, L. (1933). Epistemological problems of economics. Auburn: The Ludwig von Mises Institute.

Wagner, R. E. (2017). James M. Buchanan and liberal political economy: A rational reconstruction. Lanham, MD: Lexington.

Weyland, K. (2001). Clarifying a contested concept: Populism in the study of Latin American politics. Comparative Politics,34(1), 1–22.

Weyland, K. (2003). Latin American neopopulism. Third World Quarterly,24(6), 1095–1115.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cachanosky, N., Lopez, E.J. Rediscovering Buchanan’s rediscovery: non-market exchange versus antiseptic allocation. Public Choice 183, 461–477 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-020-00819-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-020-00819-0