Abstract

Bar-Lev and Fox (Natl Lang Semant 28:175–223, 2020), B-L&F, redefine the exhaustification operator, Exh, so that it negates innocently excludable (IE) alternatives and asserts innocently includable (II) ones. They similarly redefine the exclusive particle only so that it negates IE-alternatives and presupposes II ones. B-L&F justify their revision of only on the basis of Alxatib’s finding (in: Proceedings of NELS 44, 2014) that only presupposes free choice (FC) in cases like Kim was only allowed to eat soup or salad. I show challenges to B-L&F’s view of only and argue against extending II to its meaning. Instead I propose that FC is better treated as a “presuppositional implicature” in such cases. I show the details of how this can be done and identify the necessary (and occasionally novel) auxiliary assumptions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Notice that any alternative \(\psi \) that is entailed by \(\phi \) is predicted by this definition to not be IE with respect to it. This is because the exclusions that come from the empty set, which is a subset of C, are consistent with \(\phi \), but when \(\lnot \psi \) is added the result is contradictory. Later I will show that, when presuppositions are considered, this definition of IE makes the same prediction for alternatives that are Strawson-entailed by \(\phi \).

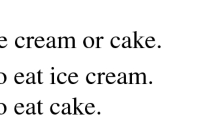

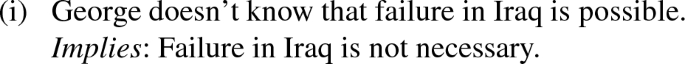

I should say that I do not think that only operates on the conjunctive alternative to a disjunctive associate. For example, it is awkward to answer the question Did Kim only eat [soup or salad] \(_{\text {F}}\)? with No, s/he ate both—certainly less awkward than answering it with No, she also ate rice. This may indicate that only does not “see” the and-alternative when its associate is a disjunctive phrase, but I will neither assume nor investigate this here, as it has little effect on my main points. In Sect. 4 I will make a similar claim, but that claim will have important consequences: I will propose that only does not see the individual disjuncts (p, q) as alternatives to a disjunctive associate.

In more technical terms, asserting r or \(p\wedge q\) affects the consistency of the inclusions that come from \(\{\}\): \(\{\}\) is a subset of C, and its grand conjunction is trivially consistent with \((\phi \wedge \textit{IE}_{\phi ,C}^{\,\lnot })\). Adding r or \(p\wedge q\) produces a contradiction because they are inconsistent with \(\textit{IE}_{\phi ,C}^{\,\lnot }\). See also footnote 2.

As the reader may have noticed, if we assume that \(\phi \) is a formal alternative to itself, then it too will be innocently includable. Strictly speaking, then, there is no need to write into Exh the assertion of the prejacent, because that follows from \(\textit{II}_{\phi ,C}\) anyway. For clarity I will still write the assertion of the prejacent separately throughout the paper.

The noted inferences in (16) can be derived if Exh appears recursively in the scope of everyone. However, B-L&F argue that a global derivation of the inference must be available also.

Crucially, note that this position is not available to B-L&F, because it would (in parallel) remove \(\Diamond p\) and \(\Diamond q\) from C in the case of (1), and would therefore leave no II-alternatives for only to presuppose.

With the right intonation, (32) can also be read as an alternative question. This is not the intended reading here.

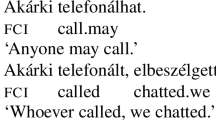

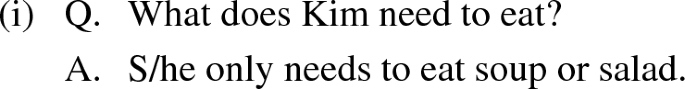

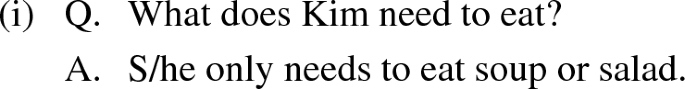

This may look like a roundabout demonstration: why did we not use question-answer congruence with a wh-question and a declarative answer, as in (i)?

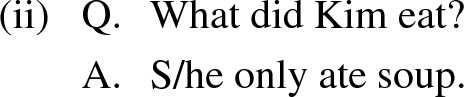

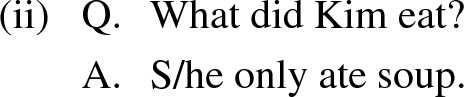

The reason is that there may be a confound. I want to show that FC is presupposed in these cases, and also that the disjunctive phrase alone is only’s associate. In (i) the answer does not intuitively presuppose FC, nor that Kim needs to eat soup or salad—indeed, how can either inference be presupposed if they are part of an informative answer to the question? This is a more general issue with only, however: independently of modality and FC, only’s prejacent “presupposition” is known to be usable as an answer to a question, as in (ii):

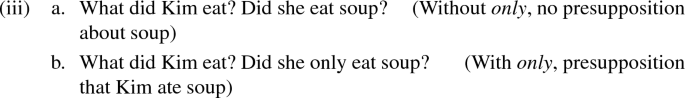

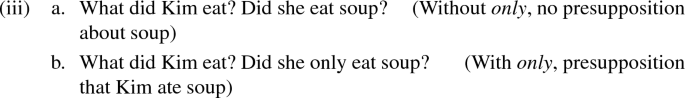

To control for this confound and highlight the presuppositional status of the prejacent, we can turn the answer into a follow-up “guess”, in the form of a yes/no-question. Doing this does indeed show only’s prejacent to be presuppositional. Note the difference between (a) and (b) below:

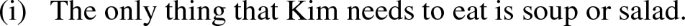

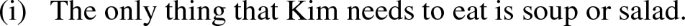

The same point is shown by the simpler but somewhat different (i):

Example (i) licenses the same inferences as (22): Kim has a requirement to eat one of soup/salad; has no requirement to eat either specifically; and has no requirement to eat anything else. And like in (22), the inferences concerning soup/salad in (i) are presupposed, as the interrogative (ii) shows:

Again, however, the structure of the sentence shows clearly that its focus is the food—the disjunction [soup or salad]—and does not concern the modality.

This is on the standard assumption that necessity modals denote universal quantifiers over possible worlds/situations.

The discussion in Spector and Sudo (2017) is much more complicated than I make it out to be here, and their motivation of the PIP does not rest solely on examples like (36). My short description of the account is sufficient for my purposes however.

Note that the PIP is not predicted to be problematic in the case of \(\textit{only}\,\Diamond (p\vee q)_{\text {F}}\). By assumption (following B-L&F, that is) the sentence presupposes FC, and FC is stronger than the presuppositions of the alternatives \(\textit{only}\,\Diamond p_{\text {F}}\) and \(\textit{only}\,\Diamond p_{\text {F}}\).

In showing this problem it was necessary to use examples that do not involve some as a focus associate, because alternatives where all takes some’s place as associate are odd (e.g., Kim only ate { \(\checkmark \) some \(_{\text {F}}\) /#all \(_{\text {F}}\) } of her dinner). I chose a scale of quantities here because it (arguably) tracks entailment.

We will make a similar move when we spell out the details of how presuppositional implicatures are derived. See Sect. 4.1.

Attentive readers will note that if we also admit alternatives where the possibility modal is replaced with a necessity modal, the incorrect assertion goes away, since none of the alternatives are innocently excludable in that case. But remember that we are testing the possibility of generating alternatives to only where unfocused material can be simplified but not replaced.

See footnote 16 for an explanation why this problem of the PIP did not come up when we looked at focused disjunctions, i.e. in the cases of \(\textit{only}\,\Box (p\vee q)_{\text {F}}\) and \(\textit{only}\,\Diamond (p\vee q)_{\text {F}}\).

Example (49) is identical to (36) from Sect. 3.2. At that time I did not refer to the ‘not-all’ inference of some as a presuppositional implicature, but used it to introduce Spector and Sudo’s (2017) PIP. From this point on I will continue to talk about these inferences as (presuppositional) implicatures, in light of the challenges to the PIP reviewed above. See Marty and Romoli (2020) for detailed discussion.

I am not considering so-called “Hurford” disjunctions like [in Paris or in France] (Hurford 1974), which are independently problematic.

Other, similar formulations are conceivable. It could be that \(\textit{only}_C\,p\) is defined only if \(\{p\}\cup C\) is either totally ordered by entailment or unordered by entailment. Note that the condition (on either version) can in principle be generalized to all scales, logical and otherwise. But I will not get into this here.

Strictly speaking, neither condition blocks the conjunctive alternative: (51) says nothing about it; (52) blocks it in the presence of independent alternatives \(\Box r/\Diamond r\) in C. If my claim in footnote 3 is correct, this result would have to be looked at more carefully.

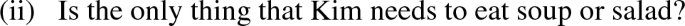

Russell (2006) also pointed out the weakness of the putative implicature in the case of know, contrary to what would be predicted from dom-exh. He also discussed an example where know is negated, but did not compare the strength of the presuppositional implicature in the two cases. See his (12), shown below as (i):

See footnote 17 for comments about the use of quantity expressions in these examples.

This conclusion has a further consequence, for it also shows that only need not make reference to IE-alternatives! I return to this in the conclusion.

\(\phi \) Strawson-entails \(\psi \) iff \(\phi \cap \textit{Dom}(\psi )\subseteq \psi \).

By the same reasoning as in footnote 2, it follows from the updated definition of IE that alternatives that are Strawson-entailed by \(\phi \) will not be IE with respect to it; the empty set of exclusions is consistent with \(\phi \), but if the strong negation of a Strawson-consequence of \(\phi \) is added, a contradiction follows.

Magri uses (87a) to explain the obligatoriness of implicatures in sentences like Some Italians come from a warm country. Such sentences are odd. Since world knowledge tells us that the sentence is equivalent to its all-alternative, it follows from (87a) that the all-alternative cannot be pruned, and that the (false) “not all” implicature is obligatory. To Magri, this explains the oddness of the sentence.

Fox (2007) made the same assumption about alternative-sets in his derivation of FC from recursive exhaustification. In \(\text {Exh}_C(\text {Exh}_{C'}(\Diamond (p\vee q)))\), \(C'\) contains the disjunctive alternatives \(\Diamond p,\Diamond q\), and C contains the pre-exhaustified alternatives \(\text {Exh}_{C'}(\Diamond p)\) and \(\text {Exh}_{C'}(\Diamond q)\). Crucially, \(C'\) in these two alternatives is the same as it is in \(\text {Exh}_{C'}(\Diamond (p\vee q))\). This makes \(\text {Exh}_{C'}(\Diamond p)\) mean \( (\Diamond p\, \& \,\lnot \Diamond q)\), and \(\text {Exh}_{C'}(\Diamond q)\) mean \( (\Diamond q\, \& \,\lnot \Diamond p)\). When these alternatives are negated by the higher Exh, we get the desired inference \((\Diamond p\leftrightarrow \Diamond q)\), which entails FC when combined with the prejacent \(\Diamond (p\vee q)\).

References

Alonso-Ovalle, Luis. 2005. Distributing the disjuncts over the modal space. In Proceedings of the 35th Annual Meeting of the North East Linguistic Society (NELS 35), ed. Leah Bateman and Cherlon Ussery, 75–86. Amherst, MA: GLSA Publications.

Alxatib, Sam. 2013. Only and association with negative antonyms. Doctoral Dissertation, MIT.

Alxatib, Sam. 2014. FC inferences under only. In Proceedings of the 44th Annual Meeting of the North East Linguistic Society (NELS 44), ed. Jyoti Iyer and Leland Kusmer, 15–28. Amherst, MA: GLSA Publications.

Bar-Lev, Moshe E. 2018. Free choice, homogeneity, and innocent inclusion. Doctoral Dissertation, Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Bar-Lev, Moshe E., and Danny Fox. 2017. Universal free choice and innocent inclusion. In Proceedings of the 27th Semantics and Linguistic Theory Conference (SALT 27), ed. Dan Burgdorf, Jacob Collard, Sireemas Maspong, and Brynhildur Stefánsdóttir, 95–115. Washington, D.C.: LSA.

Bar-Lev, Moshe E., and Danny Fox. 2020. Free choice, simplification, and innocent inclusion. Natural Language Semantics 28: 175–223.

Bonomi, Andrea, and Paolo Casalegno. 1993. Only: Association with focus in event semantics. Natural Language Semantics 2: 1–45.

Buccola, Brian. 2018. A restriction on the distribution of exclusive only. Snippets 33: 3–4.

Chemla, Emmanuel. 2009. Universal implicatures and free choice effects: Experimental data. Semantics and Pragmatics 2: 1–33.

Chierchia, Gennaro. 2004. Scalar implicatures, polarity phenomena, and the syntax/pragmatics interface. In Structure and Beyond: the Cartography of Syntactic Structures, ed. Adriana Belletti, 39–103. New York: Oxford University Press.

Crnič, Luka, Emmanuel Chemla, and Danny Fox. 2015. Scalar implicatures of embedded disjunction. Natural Language Semantics 23: 271–305.

Fine, Kit. 1975. Critical notice. Mind 84: 451–458.

Fox, Danny. 2007. Free choice and the theory of scalar implicatures. In Presupposition and implicature in compositional semantics, ed. Uli Sauerland and Penka Stateva, 71–120. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

Fox, Danny. 2018. Partition by exhaustification: Comments on Dayal 1996. In Proceedings of Sinn und Bedeutung 22, ed. Uli Sauerland and Stephanie Solt, 403–434. Berlin: Leibniz-Centre General Linguistics.

Gajewski, Jon, and Yael Sharvit. 2012. In defense of the grammatical approach to local implicatures. Natural Language Semantics 20: 31–57.

Hamblin, C.L. 1973. Questions in Montague English. Foundations of Language 10: 41–53.

Heim, Irene, and Angelika Kratzer. 1998. Semantics in generative grammar. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Hurford, James R. 1974. Exclusive or inclusive disjunction. Foundations of Language 11: 409–411.

Kratzer, Angelika, and Junko Shimoyama. 2002. Indeterminate pronouns: The view from Japanese. In Proceedings of the 3rd Tokyo Conference on Psycholinguistics, ed. Yuiko Otsu, 1–25. Tokyo: Hituzi Syobo.

Krifka, Manfred. 1993. Focus and presupposition in dynamic interpretation. Journal of Semantics 10: 269–300.

Lewis, David. 1973. Counterfactuals. Oxford: Blackwell.

Magri, Giorgio. 2009. A theory of individual-level predicates based on blind mandatory scalar implicatures. Natural Language Semantics 17: 245–297.

Marty, Paul. 2017. Implicatures in the DP domain. Doctoral Dissertation, MIT.

Marty, Paul, and Jacopo Romoli. 2020. Presupposed free choice and the theory of scalar implicatures. To appear in Linguistics and Philosophy.

Nouwen, Rick. 2018. Free choice and distribution over disjunction: The case of free choice ability. Semantics and Pragmatics 11. Available early-access at https://semprag.org/index.php/sp/article/view/sp.11.4/pdf.

Nute, Donald. 1975. Counterfactuals and the similarity of words. The Journal of Philosophy 21: 773–778.

Rooth, Mats. 1992. A theory of focus interpretation. Natural Language Semantics 1: 75–116.

Russell, Benjamin. 2006. Against grammatical computation of scalar implicatures. Journal of Semantics 23: 361–382.

Sauerland, Uli. 2004. Scalar implicatures in complex sentences. Linguistics and Philosophy 27: 367–391.

Simons, Mandy. 2006. Notes on embedded implicatures. Unpublished manuscript, Carnegie Mellon University.

Spector, Benjamin, and Yasutada Sudo. 2017. Presupposed ignorance and exhaustification: How scalar implicatures and presuppositions interact. Linguistics and Philosophy 40: 473–517.

Stalnaker, Robert. 1968. A theory of conditionals. In Studies in Logical Theory, ed. Nicholas Rescher, 98–112. Oxford: Blackwell.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

I thank an anonymous NALS reviewer, Itai Bassi, Lucas Champollion, Filipe Hisao Kobayashi, Paul Marty, Jacopo Romoli, Philippe Schlenker, Yael Sharvit, Yasutada Sudo, and audiences at Philippe Schlenker’s formal pragmatics seminar at NYU, and the 94th LSA meeting in New Orleans.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Alxatib, S. Only, or, and free choice presuppositions. Nat Lang Semantics 28, 395–429 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11050-020-09170-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11050-020-09170-y