Abstract

Objectives

In the current study we consider the link between imprisonment and post-prison participation in violent political extremism. We examine three research questions: (1) whether spending time in prison increases the post-release risk of engaging in violent acts; (2) whether political extremists who were radicalized in prison are more likely to commit violent acts than political extremists radicalized elsewhere; and (3) whether individuals who were in prison and radicalized there were more likely to engage in post-prison violent extremism compared to individuals who were in prison and did not radicalize there.

Methods

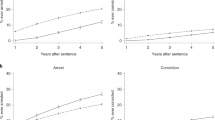

We perform a two-stage analysis where we first preprocess the data using a matching technique to approximate a fully blocked experimental design. Using the matched data, we then calculate the conditional odds ratio for engaging in violent extremism and estimate average treatment effects (ATE) of our outcomes of interest.

Results

Our results show that the effects of imprisonment and prison radicalization increases post-prison violent extremism by 78–187% for the logistic regression analysis, and 24.6–48.53% for the ATE analysis. Both analyses show that when radicalization occurs in the context of prison, the criminogenic effect of imprisonment is doubled.

Conclusions

In support of longstanding arguments that prison plays a major role in the identity and behavior of individuals after their release, we find consistent evidence that the post-prison use of politically motivated violence can be estimated in part by whether perpetrators spent time in prison and whether they were radicalized there.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We adopt the FBI (2017) definition of violent extremism as “encouraging, condoning, justifying, or supporting the commission of a violent act to achieve political, ideological, religious, social, or economic goals”.

We adopt the FBI definition of radicalization as “the process by which individuals come to believe their engagement in or facilitation of nonstate violence to achieve social and political change is necessary and justified” (Hunter and Heinke 2011).

A recent report in the New York Times claims that American prisons currently hold 443 convicted terrorists, but the reporters were unable to confirm the locations for two-thirds of the inmates identified (Fairfield and Wallace 2016).

More generally, we know of no U.S. recidivism studies that follow people who have been radicalized in prison.

Individuals could be coded as subscribing to more than one ideology. For a full description of the ideologies and coding rules, see PIRUS (2018, pp. 3–5).

We acknowledge that the time period covered by the data is quite long—in part a feature of the fact that political extremism is a relatively rare event and gathering a large data set requires a long time frame. In general, 98.1% of the cases (662 cases) in the analysis occurred after 1970 and 91.9% (620 cases) after 2000. All cases were coded retrospectively in three waves between 2013 and 2015 using the same criteria for the entire period.

A complete list of both groups is available on request.

The most common reason for eliminating cases during the criteria coding stage was their failure to meet the inclusion requirement that they had radicalized in the United States. While every effort was made to ensure the representativeness of the data, given our reliance on open-sources, we cannot rule out the possibility that our sample is also influenced by news reporting trends. For more details on the data and the data coding process, see PIRUS (2018) and Jensen et al. (2015).

Although the PIRUS team continually updates and revises the data as new information is discovered, to this point in time we have not had sufficient resources to double code the full data set.

While there is still no generally accepted tool for measuring radicalization (cf., Borum 2011; Hamm 2008; Neumann 2013) our data seeks sources that indicate that while in prison the perpetrators demonstrated either through their attitudes or behavior a growing commitment to ideologically motivated illegal action.

After performing coarsened exact matching, the sample size for H3 was even smaller: 36 out of 103 cases (35%) were pruned by the CEM algorithm, dropping the sample to 67 cases.

For this analysis, we assumed that if there was no mention of mental illness in court documents or media accounts, then none existed—a decision supported by earlier research (LaFree et al. 2018).

The regression-adjustment approach makes use of the potential outcome means to estimate the ATE; while the inverse probability weighting approach uses the propensity score.

For the percentage change coefficient and standard error, we made use of the command “nlcom,” calculated with the delta method.

We also performed an additional robustness check by using a multiple imputation method called Amelia II (Honaker et al. 2011) to ensure that the estimated likelihood of engaging in violent extremism is not being driven by our handling of missing data. We generated 5 complete data sets using Amelia II before running CEM. After establishing the validity of the 5 imputed data sets derived from Amelia II, we next used them to quantify the strength of association between violent extremism, imprisonment and radicalization. The results, available on request, were substantively identical to those reported here.

References

Abrams DE, Hogg MA (1990) Social identity theory: constructive and critical advances. Springer, New York

Akers RL (1985) Deviant behavior: a social learning approach. Wadsworth, Belmont

Akers RL, Jennings WG (2009) The social learning theory of crime and deviance. Handbook on crime and deviance. Springer, New York, pp 103–120

Austin PC, Steyerberg EW (2015) The number of subjects per variable required in linear regression analyses. J Clin Epidemiol 68(6):627–636

Bandura A (1969) Social-learning theory of identificatory processes. In: Goslin D (ed) Handbook of socialization theory and research. Rand McNally, Chicago, pp 213–262

Beckford J, Joly D, Khosrokhavar F (2016) Muslims in prison: challenge and change in Britain and France. Springer, New York

Binswanger IA, Nowels C, Corsi KF, Long J, Booth RE, Kutner J, Steiner JF (2011) “From the prison door right to the sidewalk, everything went downhill”, a qualitative study of the health experiences of recently released inmates. Int J Law Psychiatry 34(4):249–255

Blackwell M, Iacus S, King G, Porro G (2009) Coarsened exact matching in Stata. Stata J 9(4):524–546

Blazak R (2009) The prison hate machine. Criminol Public Policy 8(3):633–640

Borum R (2011) Radicalization into violent extremism I: a review of definitions and applications of social science theories. J Strateg Secur 4(4):7–36

Brandon J (2009) The danger of prison radicalization. CTC Sentinel 2(12):1–4

Brunell TL, Dinardo J (2004) A propensity score reweighting approach to estimating the partisan effects of full turnout in American presidential elections. Polit Anal 12(1):28–45

Busso M, DiNardo JE, McCrary J (2009) New evidence on the finite sample properties of propensity score matching and reweighting estimators. Unpublished manuscript, Dept. Of Economics, UC Berkeley

Carson EA, Golinelli D (2014) Prisoners in 2012: trends in admissions and releases, 1991–2012. U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, New York

Cerulli G (2015) Econometric evaluation of socio-economic programs: theory and applications. Springer, New York

Cilluffo FJ, Cardash SL, Whitehead AJ (2006a) Radicalization: behind bars and beyond borders. Brown J World Aff 13(2):113–122

Cilluffo F, Saathoff G, Lane J, Cardash S, Magarik J, Whitehead A, Raynor J, Bogis A, Lohr G (2006b) Out of the shadows: getting ahead of prisoner radicalization. Homeland Security Policy Initiative, Washington, DC

Clear T (2007) Imprisoning communities: how mass incarceration makes disadvantaged neighborhoods worse. Oxford University Press, New York

Clemmer D (1940) The prison community. Christopher Publishing House, New Braunfels

Cloud DH, Drucker E, Browne A, Parsons J (2015) Public health and solitary confinement in the United States. Am J Public Health 105(1):18–26

Comfort M (2009) Doing time together: love and family in the shadow of the prison. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Fairfield H, Wallace T (2016) The terrorists in U.S. prisons. The New York Times, April 7. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2016/04/07/us/terrorists-in-us-prisons.html. Downloaded August 19, 2018

Federal Bureau of Investigation (2017) What is violent extremism? Downloaded March 1, 2017: https://cve.fbi.gov/whatis/

Freilich JD, Chermak SM, Belli R, Gruenewald J, Parkin WS (2014) Introducing the United States extremis crime database (ECDB). Terror Polit Violence 26(2):372–384

Gartenstein-Ross D, Grossman L (2009) Homegrown terrorists in the U.S. and U.K.: an empirical examination of the radicalization process. FDD’s Center for Terrorism Research, Washington, DC

Gendreau P, Cullen FT, Goggin C (1999) The effects of prison sentences on recidivism. A report to the Corrections Research and Development and Aboriginal Policy Branch, Solicitor General of Canada. Public Works & Government Services Canada, Ottawa

Gill P, Horgan J, Deckert P (2014) Bombing alone: tracing the motivations and antecedent behaviors of lone-actor terrorists. J Forensic Sci 59(2):425–435

Goffman E (1956) The presentation of self in everyday life. Doubleday, New York

Goldstone JA, Useem B (1999) Prison riots as microrevolutions: an extension of state-centered theories of revolution. Am J Sociol 104(4):985–1029

Goodman P (2014) Race in California’s prison fire camps for men: prison politics, space, and the racialization of everyday life. Am J Sociol 120(2):352–394

Green DP, Winik D (2010) Using random judge assignments to estimate the effects of incarceration and probation on recidivism among drug offenders. Criminology 48(2):357–387

Griffin ML, Hepburn JR (2006) The effect of gang affiliation on violent misconduct among inmates during the early years of confinement. Criminal Justice Behav 33(4):419–466

Hamm M (2008) Prisoner radicalization: assessing the threat in U.S. correctional institutions. NIJ Journal, 261. http://www.nij.gov/journals/261/prisoner-radicalization.htm

Hamm M (2009) Prison Islam in the age of sacred terror. Br J Criminol 49(5):667–685

Hamm M, Spaaj R (2016) The age of lone wolf terrorism. Columbia University Press, New York

Hayes AF, Krippendorff K (2007) Answering the call for a standard reliability measure for coding data. Commun Methods Meas 1(1):77–89

Hogg MA (2007) Uncertainty–identity theory. In: Zanna MP (ed) Advances in experimental social psychology, vol 39. Academic Press, San Diego, pp 69–126

Hogg MA, Adelman J (2013) Uncertainty–identity theory: extreme groups, radical behavior, and authoritarian leadership. J Soc Issues 69(3):436–454

Hogg MA, Sherman DK, Dierselhuis J, Maitner AT, Moffitt G (2007) Uncertainty, entitativity, and group identification. J Exp Soc Psychol 43(1):135–142

Hogg MA, Meehan C, Farquharson J (2010) The solace of radicalism: self-uncertainty and group identification in the face of threat. J Exp Soc Psychol 46(6):1061–1066

Honaker J, King G, Blackwell M (2011) Amelia II: a program for missing data. J Stat Softw. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v045.i07

Horgan J (2005) The psychology of terrorism. Routledge, London

Huebner BM (2005) The effect of incarceration on marriage and work over the life course. Justice Q 22(3):281–303

Hunter R, Heinke D (2011) Radicalization of Islamic terrorists in the western world. FBI Law Enforc Bull 80:25

Iacus SM, King G, Porro G (2012) Causal inference without balance checking: coarsened exact matching. Polit Anal 20(1):1–24

Imbens GW, Rubin DB (2015) Causal inference in statistics, social, and biomedical sciences. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Jasko K, LaFree G, Kruglanski A (2017) Quest for significance and violent extremism: the case of domestic radicalization. Polit Psychol 38(5):815–831

Jensen M, James P, Tinsley H (2015) Profiles of individual radicalization in the United States: an empirical assessment of domestic radicalization. Retrieved from https://www.start.umd.edu/pubs/PIRUS%20Fact%20Sheet_Jan%202015.pdf

Jones CR (2014) Are prisons really schools for terrorism? Challenging the rhetoric on prison radicalization. Punishm Soc 16(1):74–103

Khosrokhavar F (2013) Radicalization in prison: the French case. Politics Relig Ideol 4(2):284–306

King G, Nielsen R (2016) Why propensity scores should not be used for matching. Working paper. Retrieved from http://j.mp/2ovYGsW

Klein GC (2007) An investigation: have Islamic fundamentalists made contact with white supremacists in the United States? J Police Crisis Negot 7(1):85–101

Kreager DA, Schaefer DR, Bouchard M, Haynie DL, Wakefield S, Young J, Zajac G (2016) Toward a criminology of inmate networks. Justice Q 33(6):1000–1028

Kruglanski AW, Gelfand MJ, Bélanger JJ, Sheveland A, Hetiarachchi M, Gunaratna R (2014) The psychology of radicalization and deradicalization: how significance quest impacts violent extremism. Polit Psychol 35:69–93

Kurzman C (2017) Muslim-American involvement with violent extremism, 2016. Triangle Center on Terrorism and Homeland Security

LaFree G, Jensen MA, James PA, Safer-Lichtenstein AB (2018) Correlates of violent political extremism in the United States. Criminology 56(2):233–268

Li Q, Racine JS, Wooldridge JM (2009) Efficient estimation of average treatment effects with mixed categorical and continuous data. J Bus Econ Stat 27:206–223

Lindquist CH (2000) Social integration and mental well-being among jail inmates. Sociol Forum 15(3):431–455

Massoglia M (2008) Incarceration as exposure: the prison, infectious disease, and other stress-related illnesses. J Health Soc Behav 49(1):56–71

Massoglia M, Firebaugh G, Warner C (2013) Racial variation in the effect of incarceration on neighborhood attainment. Am Sociol Rev 78(1):142–165

McCauley C, Moskalenko S (2011) Friction: how radicalization happens to them and us. Oxford University Press, New York

Mears DP, Cochran JC, Siennick SE, Bales WD (2012) Prison visitation and recidivism. Justice Q 29(6):888–918

Moghaddam F (2004) Cultural preconditions for potential terrorist groups: terrorism and societal change. In: Moghaddam FM, Marsella AJ (eds) Understanding terrorism: psychosocial roots, consequences, and interventions. American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, pp 201–217

Monahan J (2017) The individual risk assessment of terrorism. In: LaFree G, Freilich JD (eds) The handbook of the criminology of terrorism. Wiley, Hoboken, pp 520–534

Morgan SL, Winship C (2014) Counterfactuals and causal inference: methods and principles for social research. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Mueller R (2006) Remarks for Delivery by FBI Director Robert Mueller at City Club, Cleveland, Ohio

Mulcahy E, Merrington S, Bell PJ (2013) The radicalisation of prison inmates: a review of the literature on recruitment, religion and prisoner vulnerability. J Hum Secur 9(1):4–14

Nagin DS, Cullen FT, Jonson CL (2009) Imprisonment and reoffending. Crime Justice 38(1):115–200

Neumann PR (2010) Prisons and terrorism: radicalization and de-radicalization in 15 countries. International Centre for the Study of Radicalization and Political Violence (ICSR), King’s College, London

Neumann PR (2013) The trouble with radicalization. Int Aff 89(4):873–893

Nguyen H, Loughran TA, Paternoster R, Fagan J, Piquero AR (2017) Institutional placement and illegal earnings: examining the crime school hypothesis. J Quant Criminol 33(2):207–235

Pape RA (2006) Dying to win. Gibson Square Books, London

Patterson EJ (2010) Incarcerating death: mortality in US state correctional facilities, 1985–1998. Demography 47(3):587–607

Peduzzi P, Concato J, Kemper E, Holford TR, Feinstein AR (1996) A simulation study of the number of events per variable in logistic regression analysis. J Clin Epidemiol 49(12):1373–1379

Peterson D, Taylor TJ, Esbensen FA (2004) Gang membership and violent victimization. Justice Q 21(4):793–815

Profiles of Individual Radicalization (PIRUS) (2018) Online codebook: http://www.start.umd.edu/sites/default/files/files/research/PIRUSCodebook.pdf. Downloaded August 16, 2018

Rabasa A, Pettyjohn SL, Ghez JJ, Boucek C (2010) Deradicalizing Islamist Extremists. RAND Corp Arlington VA National Security Research Div

Robins JM, Hernan MA, Brumback BA (2000) Marginal structural models and causal inference in epidemiology. Epidemiology 11(5):550–560

Rose DR, Clear TR (1998) Incarceration, social capital, and crime: implications for social disorganization theory. Criminology 36(3):441–480

Safer-Lichtenstein A, LaFree G, Loughran T (2017) Studying terrorism empirically: what we know about what we don’t know. J Contemp Crim Justice 33(3):273–291

Sageman M (2004) Understanding terror networks. University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia

Schaefer DR, Bouchard M, Young JT, Kreager DA (2017) Friends in locked places: an investigation of prison inmate network structure. Soc Netw 51:88–103

Schmid TJ, Jones RS (1993) Ambivalent actions: prison adaptation strategies of first-time, short-term inmates. J Contemp Ethnogr 21(4):439–463

Shane S (2011) Beyond Guantanamo, a web of prisons for terrorism inmates. The New York Times, December 10, 2011

Silke A (2008) Holy warriors: exploring the psychological processes of jihadi radicalization. Eur J Criminol 5(1):99–123

Silke A (ed) (2014) Prisons, terrorism and extremism: critical issues in management, radicalisation and reform. Routledge, London

Skarbek D (2014) The social order of the underworld: how prison gangs govern the American penal system. Oxford University Press, New York

Smith BL, Damphousse KR (2003) The American terrorism study. Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research, Ann Arbor

StataCorp (2013) Stata 13 Treatment-effects reference manual. Stata Press, College Station

Stuart EA (2010) Matching methods for causal inference: a review and a look forward. Stat Sci 25(1):1–21

Sutherland EH (1947) Principles of criminology: a sociological theory of criminal behavior. J. B. Lippincott, Philadelphia

Sykes G (1958) The society of captives: a study of a maximum security prison. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Sykes BL, Pettit B (2014) Mass incarceration, family complexity, and the reproduction of childhood disadvantage. Ann Am Acad Polit Soc Sci 654(1):127–149

The Sentencing Project (2009) Retrieved from http://www.sentencingproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Annual-Report-TSP-2009.pdf

Trammell R (2012) Enforcing the convict code: violence and prison culture. Lynne Rienner, Boulder

Tregea W, Larmour M (2009) The prisoners’ world: portraits of convicts caught in the incarceration binge. Lexington, Lanham

Useem B, Clayton O (2009) Radicalization of U.S. prisoners. Criminol Public Policy 8(3):561–592

Useem B, Kimball P (1991) States of siege: US prison riots, 1971–1986. Oxford University Press, New York

Vittinghoff E, McCulloch CE (2007) Relaxing the rule of ten events per variable in logistic and Cox regression. Am J Epidemiol 165(6):710–718

Walker ML (2016) Race making in a penal institution. Am J Sociol 121(4):1051–1078

Webber D, Chernikova M, Kruglanski AW, Gelfand MJ, Hettiarachchi M, Gunaratna R, Belanger JJ (2016) Deradicalizing the tamil tigers. Unpublished manuscript, University of Maryland, College Park, MD

Western B (2002) The impact of incarceration on wage mobility and inequality. Am Sociol Rev 67(4):526–546

Western B, Kling JR, Weiman DF (2001) The labor market consequences of incarceration. Crime Delinq 47(3):410–427

Wooldridge JM (2010) Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data, vol 2. MIT Press, Cambridge

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

LaFree, G., Jiang, B. & Porter, L.C. Prison and Violent Political Extremism in the United States. J Quant Criminol 36, 473–498 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-019-09412-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-019-09412-1