Abstract

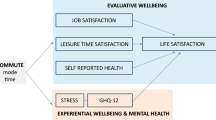

Prior research has documented linear detrimental effects of commuting on individuals’ life satisfaction: the longer individuals’ daily commute, the less satisfied they are with their life. An inspection of the available longitudinal evidence suggests that this conclusion is almost exclusively based on a continuous operationalization of commuting time and distance with a focus on a linear relationship. In contrast, cross-sectional evidence indicates preliminary evidence for non-linear effects and suggests that negative effects of commuting are particularly likely when commuting exceeds a certain threshold of time or distance. Relying on nationally representative data for Germany, the present study applies longitudinal modelling comparing estimates from a continuous and a categorical operationalization. Results clearly indicate a non-linear association and show that negative effects of commuting are almost completely due to individuals who commute more than 80 km (50 miles) daily per way. These findings are in conflict with prior research (partly resting on the same data) proposing a linear relationship. Further analyses suggest that satisfaction with leisure time is a significant mediator of the observed non-linear effect. Results are discussed in light of prior theorizing on the consequences of commuting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The data were provided by the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW Berlin). A detailed description of the GSOEP can be found in Wagner et al. (2007).

We tested the robustness of the chosen operationalization against several other possible categorizations, all of which led to similar results.

The CASMIN classification contains the following levels of education: inadequately completed (1a), general elementary education (1b), basic vocational qualification (1c), intermediate vocational qualification (2a), intermediate general qualification (2b), general maturity certificate (2c), vocational maturity certificate (2c) lower tertiary education (3a) and higher tertiary education (3b). For more information on CASMIN, see Brauns et al. (2003). For simplification, the CASMIN levels are grouped as follows: low educational attainment (CASMIN levels 1a–1c), medium educational attainment (CASMIN levels 2a–2c) and high educational attainment (CASMIN levels 3a–3b).

Past research suggests that the relationship between income and life satisfaction is best expressed by a logarithmic term (e.g., Wolbring et al. 2013). The household equivalence income allows to compare the financial well-being of a household independent of the households’ structure. It is measured by summing all household members’ income and then dividing by the square root of the household size.

In contrast to that, further analyses reveal no association between commuting distance on the one hand and feeling worried or angry on the other.

References

Allison, P. D. (2009). Fixed effects regression models. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Argyle, M. (2001). The psychology of happiness. London: Routledge.

Blanchflower, D. G., & Oswald, A. J. (2008). Is well-being U-shaped over the life cycle? Social Science and Medicine,66(8), 1733–1749.

Brauns, H., Scherer, S., & Steinmann, S. (2003). The CASMIN educational classification in international comparative research. In J. H. P. Hoffmeyer-Zlotnik & C. Wolf (Eds.), Advances in cross-national comparison. An European working book for demographic and socio-economic variables (pp. 196–221). New York: Kluwer and Plenum.

Brüderl, J., & Ludwig, V. (2015). Fixed-effects panel regression. In H. Best & C. Wolf (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of regression analysis and causal inference (pp. 327–358). London: SAGE Publications.

Cummins, R. A. (1996). The domains of life satisfaction: An attempt to order chaos. Social Indicators Research,38, 303–332.

DeNeve, K. M., & Cooper, H. (1998). The happy personality: A meta-analysis of 137 personality traits and subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin,124(2), 197–229.

Dickerson, A., Hole, A. R., & Munford, L. A. (2014). The relationship between well-being and commuting revisited: Does the choice of methodology matter? Regional Science and Urban Economics,49, 321–329.

Diener, E. (2012). New findings and future directions for subjective well-being research. American Psychologist,67(8), 590–597.

Diener, E. (2013). The remarkable changes in the science of subjective well-being. Perspectives on Psychological Science,8(6), 663–666.

Dolan, P., Peasgood, T., & White, M. (2008). Do we really know what makes us happy? A review of the economic literature on the factors associated with subjective well-being. Journal of Economic Psychology,29, 94–122.

Drobnič, S., Beham, B., & Präg, P. (2010). Good job, good life? Working conditions and quality of life in Europe. Social Indicators Research,99(2), 205–225.

Evans, G. W., & Wener, R. E. (2006). Rail commuting duration and passenger stress. Health Psychology,25(3), 408–412.

Evans, G. W., Wener, R. E., & Phillips, D. (2002). The morning rushhour. Predictability and commuter stress. Environment and Behavior,34(4), 521–530.

Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A., & Frijters, P. (2004). How important is methodology for the estimates of the determinants of happiness? The Economic Journal,114(497), 641–659.

Frey, B. S., & Stutzer, A. (2014). Economic consequences of mispredicting utility. Journal of Happiness Studies,15(4), 937–956.

Gerlach, K., & Stephan, G. (1992). Pendelzeiten und Entlohnung - eine Untersuchung mit Individualdaten für die Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Jahrbuch für Sozialökonomie und Statistik,210(1–2), 18–34.

Gottholmseder, G., Nowotny, K., Pruckner, G. J., & Theurl, E. (2009). Stress perception and commuting. Health Economics,18(5), 559–576.

Hansson, E., Mattisson, K., Björk, J., Östergren, P.-O., & Jakobsson, K. (2011). Relationship between commuting and health outcomes in a cross-sectional population survey in southern Sweden. BMC Public Health,11, 834.

Hennessy, D. A., & Wiesenthal, D. L. (1999). Traffic congestion, driver stress, and driver aggression. Aggressive Behavior,25(6), 409–423.

Hilbrecht, M., Smale, B., & Mock, S. E. (2014). Highway to health? Commute time and well-being among Canadian adults. World Leisure Journal,56(2), 151–163.

Jain, J., & Lyons, G. (2008). The gift of travel time. Journal of Transport Geography,16(2), 81–89.

Kageyama, T., Nishikodo, N., Kobayashi, T., Kurokawa, Y., Kenko, T., & Kabuto, M. (1998). Long commuting time, extensive overtime, and sympathodominant state assessed in terms of short-term heart rate variability among male white-collar workers in the Tokyo megalopolis. Industrial Health,36, 209–217.

Kahneman, D. (1999). Objective happiness. In D. Kahneman, E. Diener, & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Well-being: The foundations of hedonic psychology (pp. 3–25). New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Kahneman, D., Krueger, A. B., Schkade, D. A., Schwarz, N., & Stone, A. A. (2004). A survey method for characterizing daily life experience: The day reconstruction method. Science,306(5702), 1776–1780.

Karlström, A., & Isacsson, G. (2009). Is sick absence related to commuting travel time? Swedish evidence based on the generalized propensity score estimator. Swedish National Road and Transport Research Institute (VTI). Working paper, 2010:3.

Kluger, A. N. (1998). Commute variability and strain. Journal of Organizational Behavior,19(2), 147–165.

Koslowsky, M., Kluger, A. N., & Reich, M. (2013). Commuting stress: Causes, effects, and methods of coping. New York: Springer.

Künn-Nelen, A. (2015). Does commuting affect health? IZA discussion papers, no. 9031. Institute of Labor Economics (IZA).

Levinson, D. M. (1998). Accessibility and the journey to work. Journal of Transport Geography,6(1), 11–21.

Lorenz, O. (2018). Does commuting matter to subjective well-being? Journal of Transport Geography,66(C), 180–199.

Lyons, G., & Chatterjee, K. (2008). A human perspective on the daily commute: Costs, benefits and trade-offs. Transport Reviews,28(2), 181–198.

Lyons, G., Jain, J., & Holley, D. (2007). The use of travel time by rail passengers in Great Britain. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice,41(1), 107–120.

Lyons, G., & Urry, J. (2005). Travel time use in the information age. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice,39(2–3), 257–276.

Lyubomirsky, S. (2001). Why are some people happier than others? The role of cognitive and motivational processes in well-being. American Psychologist, 56(3), 239–249.

Mokhtarian, P. L., & Salomon, I. (2001). How derived is the demand for travel? Some conceptual and measurement considerations. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice,35(8), 695–719.

Morris, E. A., & Zhou, Y. (2018). Are long commutes short on benefits? Commute duration and various manifestations of well-being. Travel Behaviour and Society,11, 101–110.

Myers, D. G. (1999). Close relationships and quality of life. In D. Kahneman, E. Diener, & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Well-being: The foundations of hedonic psychology (pp. 374–391). New York, NY, US: Russell Sage Foundation.

Nie, P., & Sousa-Poza, A. (2015). Commute time and subjective well-being in urban China. Hohenheim discussion papers in Business, Economics and Social Sciences, No. 09-2015. http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bsz:100-opus-11484. Accessed 1 Mar 2018.

Novaco, R. W., Stokols, D., & Milanesi, L. (1990). Objective and subjective dimensions of travel impedance as determinants of commuting stress. American Journal of Community Psychology,18(2), 231–257.

Office for National Statistics. (2014). Commuting and personal well-being, 2014. London: Office for National Statistics.

Olsson, L. E., Gärling, T., Ettema, D., Friman, M., & Fujii, S. (2013). Happiness and satisfaction with work commute. Social Indicators Research,111(1), 255–263.

Ory, D. T., Mokhtarian, P. L., Redmond, L. S., Salomon, I., Collantes, G. O., & Choo, S. (2004). When is commuting desirable to the individual? Growth and Change,35(3), 334–359.

Pfaff, S. (2014). Pendelentfernung, Lebenszufriedenheit und Entlohnung: Eine Längsschnittuntersuchung mit den Daten des SOEP von 1998 bis 2009. Zeitschrift für Soziologie,43(2), 113–130.

Roberts, J., Hodgson, R., & Dolan, P. (2011). “It’s driving her mad”. Gender differences in the effects of commuting on psychological health. Journal of Health Economics,30(5), 1064–1076.

Rouwendal, J. (2004). Search theory and commuting behavior. Growth and Change,35(3), 391–418.

Schwarz, N., & Strack, F. (1999). Reports of subjective well-being: Judgmental processes and their methodological implications. In D. Kahneman, E. Diener, & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Well-being: The foundations of hedonic psychology (pp. 61–84). New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Siegrist, J. (1996). Adverse health effects of high-effort/low-reward conditions. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology,1(1), 27–41.

Sposato, R. G., Röderer, K., & Cervinka, R. (2012). The influence of control and related variables on commuting stress. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour,15(5), 581–587.

Statistisches Bundesamt. (2015). Qualität der Arbeit. Geld verdienen und was sonst noch zählt. Wiesbaden.

Stokols, D., Novaco, R. W., Stokols, J., & Campbell, J. (1978). Traffic congestion, type A behavior, and stress. Journal of Applied Psychology,63(4), 467–480.

Stutzer, A., & Frey, B. S. (2007). Commuting and life satisfaction in Germany. Informationen zur Raumentwicklung,2(3), 179–189.

Stutzer, A., & Frey, B. S. (2008). Stress that doesn’t pay. The commuting paradox. Scandinavian Journal of Economics,110(2), 339–366.

Van Ommeren, J., Rietveld, P., & Nijkamp, P. (1997). Commuting: In search of jobs and residences. Journal of Urban Economics,42(3), 402–421.

Wagner, G. G., Frick, J. R., & Schupp, J. (2007). The German socio-economic panel study (SOEP)—scope, evolution and enhancements. Schmollers Jahrbuch,127(1), 139–169.

Walsleben, J. A., Norman, R. G., Novak, R. D., O’Malley, E. B., Rapoport, D. M., & Strohl, K. P. (1999). Sleep habits of Long Island rail road commuters. Sleep,22(6), 728–734.

Wener, R. E., Evans, G. W., Phillips, D., & Nadler, N. (2003). Running for the 7:45: The effects of public transit improvements on commuter stress. Transportation,30, 203–220.

Wolbring, T., Keuschnigg, M., & Negele, E. (2013). Needs, comparisons, and adaptation: The importance of relative income for life satisfaction. European Sociological Review,29(1), 86–104.

Zhu, J., & Fan, Y. (2018). Commute happiness in Xi’an, China: Effects of commute mode, duration, and frequency. Travel Behaviour and Society,11, 43–51.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Appendix

Appendix

See Tables 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ingenfeld, J., Wolbring, T. & Bless, H. Commuting and Life Satisfaction Revisited: Evidence on a Non-linear Relationship. J Happiness Stud 20, 2677–2709 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-018-0064-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-018-0064-2