Abstract

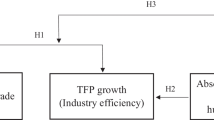

Using a distinctive sectoral dataset from Ireland, among the most attractive destinations of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), over the period 2000 and 2018, we evaluate the role of embodied and disembodied spillovers in labour productivity. The paper fills substantial gaps in the literature of FDI led productivity gains. First, we examine how (embodied) spillovers from different sourcing strategies of MNEs (material versus service linkages) affect the trajectory of sectoral productivity. Second, we evaluate the role of (disembodied) spillovers emerging from the intensity of foreign royalties and employee training. Third, we account in a relative manner for the absorptive capacity of domestic sectors, as a prerequisite for facilitating knowledge spillovers. Instead of purely measuring the level of human capital in the sector, we use the educational gap between domestic firms and Multi-national Enterprises (MNEs) in the same sector. After incorporating these new elements, the analysis shows that embodied spillovers through the material linkage are positively associated with domestic labour productivity (LP), nonetheless gains vary substantially across segments of the productivity distribution. The service linkage impacts negatively unless sectors get close to the educational frontier. Our results are robust for selectivity bias offering ample space for policy design and intervention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availibility Statement

Data are available from the authors upon request.

Change history

08 July 2023

The original version of this paper was updated to correct the spelling of Université.

Notes

Negative effects from backward spillovers are rather rare in the literature, see for example, Xu and Sheng (2012) for a study on Chinese manufacturing firms.

See Hynes et al. (2020) for a recent study on the role of materials and services linkages in firm performance without identifying, though, where these inputs are purchased from (foreign or domestic firms).

Services offshoring usually initializes structural changes within firms allowing to deploy more innovation and R &D oriented activities (Bournakis et al. 2018).

Although there is no direct shared ownership (with domestic firms) upon these proprietary assets, unintended diffusion of knowledge from MNE subsidiaries always occurs due to the de-motivation of managers and their limited authority to decide on the use of income generated from these assets (Foss et al. 2012; Hart 2017). Decisions are taken by the MNEs’ headquarters, which points to a typical hazard problem between headquarters and the manager of the foreign affiliate, similar to the principal-agent challenge resulting in unintended technology diffusion to local firms (Grossman and Hart 1986).

The staggered difference-in-differences approach treats supply of materials or services to MNEs (the event) in a dynamic setting allowing plotting graphs that show in an intuitive way the post-treatment effects Schmidheiny and Siegloch (2020); De Chaisemartin and d’Haultfoeuille (2020), and Freyaldenhoven et al. (2019).

The drop in net FDI inflows in 2019 was due to the one-off transactions such as mergers and the shifting of assets around companies within multinational groups. Please See the Central Statistics Office International Accounts Q2 2019 report CSO.

The population of the ABSEI survey also includes a small number of High-Potential Start-Up (HPSU) companies with the employment of less than 10 where there is an expectation that their employment will exceed 10 in the following survey.

The labour cost is the average payroll cost (i.e. wage per employee) in Manufacturing and international traded services.

Years of schooling are country-level data from Barro and Lee (2015).

Appendix A, Fig. 6 shows the sample average of LP for the period under study.

The National Programme launched initially in the 1980 s.

Specific point estimates are not reported in the Table but they are available from the authors upon request.

Non-linear efects are present with substantial heterogeneity in the FDI effects as firms move to different segments of the productivity distribution Girma and Görg (2005).

We illustrate a plot of the Cumulative Distribution Function (CDF) of LP (in logs) in Appendix A, Fig. 5. The graph is reasonably symmetric with the 10th, 50th and 90th quantiles to be approximately 1.5, 1.75, and 2.0 on the log scale of LP.

References

Alfaro A, Manelici I, Vásquez JP (2022) The Effects of Joining Multinational Supply Chains: New Evidence from Firm-To-Firm Linkages. Q J Econ 1–58

Alfaro L, Chanda A, Kalemli-Ozcan S et al (2004) FDI and Economic Growth: the Role of Local Financial Markets. J Int Econ 64(1):89–112

Amiti M, Wei SJ (2009) Service Offshoring and Productivity: Evidence from the US. World Econ 32(2):203–220

Barrett A, Bergin A, FitzGerald J, et al (2015) Scoping the Possible Economic Implications of Brexit on Ireland. Economic and Social Research Institute Dublin

Barrios S, Strobl E (2002) Foreign Direct Investment and Productivity Spillovers: Evidence from the Spanish Experience. Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv 138(3):459–481

Barrios S, Görg H, Strobl E (2011) Spillovers Through Backward Linkages from Multinationals: Measurement Matters! Eur Econ Rev 55(6):862–875

Barro RJ, Lee JW (2015) Education Matters. Global Schooling Gains from the 19th to the 21st Century. Oxford University Press

Barry F (2019) Ireland and the Changing Global Foreign Direct Investment Landscape. Administration 67(3):93–110

Bergin A, Economides P, Abian GR, et al (2019) Ireland and Brexit: Modelling the Impact of Deal and No-Deal Scenarios. Q Econ Comment Spec Artic

Blalock G, Gertler PJ (2008) Welfare Gains from Foreign Direct Investment Through Technology Transfer to Local Suppliers. J Int Econ 74(2):402–421

Blalock G, Gertler PJ (2009) How Firm Capabilities Affect Who Benefits from Foreign Technology. J Dev Econ 90(2):192–199

Bohle D, Regan A (2021) The Comparative Political Economy of Growth Models: Explaining the Continuity of FDI-Led Growth in Ireland and Hungary. Polit Soc 49(1):75–106

Borensztein E, De Gregorio J, Lee JW (1998) How Does Foreign Direct Investment Affect Economic Growth? J Int Econ 45(1):115–135

Bournakis I (2021) Spillovers and Productivity: Revisiting the Puzzle with EU Firm Level Data. Econ Lett 201:109804

Bournakis I, Vecchi M, Venturini F (2018) Off-Shoring, Specialization and R &D. Rev Income Wealth 64(1):26–51

Bournakis I, Papaioannou S, Papanastassiou M (2022) Multinationals and Domestic Total Factor Productivity: Competition Effects, Knowledge Spillovers and Foreign Ownership. World Econ 1–36

Brainard SL (1993) A Simple Theory of Multinational Corporations and Trade With a Trade-Off Between Proximity and Concentration. Tech. rep., National Bureau of Economic Research

Buckley PJ, Ruane F (2006) Foreign Direct Investment in Ireland: Policy Implications for Emerging Economies. World Econ 29(11):1611–1628

Chanegriha M, Stewart C, Tsoukis C (2020) Testing for Causality Between FDI and Economic Growth Using Heterogeneous Panel Data. J Int Trade Econ Dev 29(5):546–565

De Chaisemartin C, d’Haultfoeuille X (2020) Two-Way Fixed Effects Estimators with Heterogeneous Treatment Effects. Am Econ Rev 110(9):2964–96

Deryugina T (2017) The Fiscal Cost of Hurricanes: Disaster Aid Versus Social Insurance. Am Econ J Econ Policy 9(3):168–98

Doornik JA, Hansen H (2008) An Omnibus Test for Univariate and Multivariate Normality. Oxf Bull Econ Stat 70:927–939

Durham JB (2004) Absorptive Capacity and the Effects of Foreign Direct Investment and Equity Foreign Portfolio Investment on Economic Growth. Eur Econ Rev 48(2):285–306

Foss K, Foss NJ, Nell PC (2012) MNC Organizational Form and Subsidiary Motivation Problems: Controlling Intervention Hazards in the Network MNC. J Int Manag 18(3):247–259

Francois J, Hoekman B (2010) Services Trade and Policy. J Econ Lit 48(3):642–92

Freyaldenhoven S, Hansen C, Shapiro JM (2019) Pre-event Trends in the Panel Event-Study Design. Am Econ Rev 109(9):3307–38

Girma S (2005) Absorptive Capacity and Productivity Spillovers from FDI: a Threshold Regression Analysis. Oxf Bull Econ Stat 67(3):281–306

Girma S, Görg H (2005) Foreign Direct Investment. Evidence from Quantile Regressions: Spillovers and Absorptive Capacity

Görg H, Seric A (2016) Linkages with Multinationals and Domestic Firm Performance: the Role of Assistance for Local Firms. Eur J Dev Res 28(4):605–624

Görg H, Hanley A, Strobl E (2011) Creating Backward Linkages from Multinationals: is There a Role for Financial Incentives? Rev Int Econ 19(2):245–259

Gorodnichenko Y, Svejnar J, Terrell K (2014) When Does FDI Have Positive Spillovers? Evidence from 17 Transition Market Economies. J Comp Econ 42(4):954–969

Grossman SJ, Hart OD (1986) The Costs and Benefits of Ownership: a Theory of Vertical and Lateral Integration. J Polit Econ 94(4):691–719

Hart O (2017) Incomplete Contracts and Control. Am Econ Rev 107(7):1731–52

Haskel JE, Pereira SC, Slaughter MJ (2007) Does Inward Foreign Direct Investment Boost the Productivity of Domestic Firms? Rev Econ Stat 89(3):482–496

He Y, Maskus KE (2012) Southern Innovation and Reverse Knowledge Spillovers: a Dynamic FDI Model. Int Econ Rev 53(1):279–302

Helpman E (1984) A Simple Theory of International Trade with Multinational Corporations. J Polit Econ 92(3):451–471

Hynes K, Kwan YK, Foley A (2019) Local linkages: The interdependence of foreign and domestic firms in ireland. Econ Model

Hynes K, Kwan YK, Foley A (2020) Local Linkages: the Interdependence of Foreign and Domestic Firms in Ireland. Econ Model 85:139–153

Keller W (2010) International Trade, Foreign Direct Investment, and Technology Spillovers. In: Handbook of the Economics of Innovation, vol 2. Elsevier, p 793–829

Koenker R, Bassett Jr G (1978) Regression Quantiles. Econometrica J Econ Soc 33–50

Kugler M (2006) Spillovers from Foreign Direct Investment: Within or Between Industries? J Dev Econ 80(2):444–477

Lane PR, Ruane F (2006) Globalisation and the Irish Economy. IIIS Occasional Paper 1

MacGaughey SL, Raimondos-Møller P, Funding La Cour L (2018) What is a Foreign Firm? Implications for Productivity Spillovers. Tech. rep., CESifo Working Paper

Mariotti S, Nicolini M, Piscitello L (2013) Vertical Linkages Between Foreign MNEs in Service Sectors and Local Manufacturing Firms. Struct Chang Econ Dyn 25:133–145

McHale J, Harold J, Mei JC et al (2022) Stars as catalysts: An Event-Study Analysis of the Impact of Star-Scientist Recruitment on Research Performance in a Small Open Economy. J Econ Geogr 00:1–27

Mei JC (2021) Refining Vertical Productivity Spillovers from FDI: Evidence from 32 Economies. Int Rev Econ Finance

Nelson RR, Phelps ES (1966) Investment in Humans, Technological Diffusion, and Economic Growth. Am Econ Rev 56(1/2):69–75

Newman C, Rand J, Talbot T et al (2015) Technology Transfers, Foreign Investment and Productivity Spillovers. Eur Econ Rev 76:168–187

Orlic E, Hashi I, Hisarciklilar M (2018) Cross Sectoral FDI Spillovers and their Impact on Manufacturing Productivity. Int Bus Rev 27(4):777–796

Schmidheiny K, Siegloch S (2020) On Event Studies and Distributed-Lags in Two-Way Fixed Effects Models: Identification, Equivalence, and Generalization. ZEW-Centre Eur Econ Res Discus Pap (20-017)

Sembenelli A, Siotis G (2008) Foreign Direct Investment and Mark-Up Dynamics: Evidence from Spanish Firms. J Int Econ 76(1):107–115

Siotis G (2003) Competitive Pressure and Economic Integration: an Illustration for Spain, 1983–1996. Int J Ind Organ 21(10):1435–1459

Smarzynska Javorcik B (2004) Does Foreign Direct Investment Increase the Productivity of Domestic Firms? In Search of Spillovers Through Backward Linkages. Am Econ Rev 94(3):605–627

Sun L, Abraham S (2021) Estimating Dynamic Treatment Effects in Event Studies with Heterogeneous Treatment Effects. J Econ 225(2):175–199

Woo J (2009) Productivity Growth and Technological Diffusion Through Foreign Direct Investment. Econ Inq 47(2):226–248

Wooldridge JM (2003) Cluster-Sample Methods in Applied Econometrics. Am Econ Rev 93(2):133–138

Xu X, Sheng Y (2012) Productivity Spillovers from Foreign Direct Investment: Firm-Level Evidence from China. World Dev 40(1):62–74

Zaheer S (2015) Overcoming the liability of foreignness. Int Bus Strateg 362–380

Funding

No Funding received for this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Data are available from the authors upon request.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The paper complies fully with the ethical requirements of the journal.

Consent for publication

The submitted work is original and has not been published or considered for publication elsewhere.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no financial interests related to the paper.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A: Descriptive Evidence

Appendix B: Definition of Variables

This section provides information about the additional variables used in Tables 1 and 2. The controls capture foreign competition from the agglomeration of economic activity within the same industry (\(Foreign_{jt}\)), export intensity of MNEs (\(Export_{jt}\)), and price–cost margins (\(PM_{jt}\)).

Foreign competition is defined as the share of total sales of MNEs over the total sales of all firms in the same sector, defined as:

where \(FS_{jt}\) represents the total sales of all MNEs in sector j at time t, and \(TS_{jt}\) represents the total sales of all firms in sector j. This measure represents the.

The second measure captures the spillover effect from MNEs export intensity. The export-orientation of MNEs induces learning effects that can potentially benefit productivity of domestic sectors. The variable is defined as:

where \(FE_{jt}\) is the total exports in manufacturing and international traded services of all foreign-owned firms in sector j at time t, hence \(Export_{jt}\) captures the foreign export intensity.

The third variable captures the relationship between sectoral productivity and market conduct. We need to isolate the competition effects from potential FDI spillovers. We construct a measure of price–cost margins, following Siotis (2003) and Sembenelli and Siotis (2008) as:

where \(ValueAdded_{jt}\) refers to the total value added of MNEs in sector j at time t, \(Payroll_{jt}\) represents the total payroll cost of MNEs in sector j at time t, \(NetCostsMaterials_{jt}\) refers to the total cost in materials of MNEs in sector j at time t.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Bournakis, I., Mei, JC. Embodied and Disembodied Spillovers from FDI: Sectoral Evidence from Ireland. J Ind Compet Trade 23, 59–80 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10842-023-00397-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10842-023-00397-z