Abstract

Brazil’s private health insurance market is the second largest in the world, behind only the United States, making it a valuable source of real-world evidence. This paper documents how physicians' inpatient reimbursement fees vary in the country and explores the relationship between these fees and the market share of health providers and health insurance companies. We implement a fixed-effects panel regression and take advantage of an unprecedented database that contains national administrative records of inpatient procedures paid by health insurance companies in 2016. We find a positive correlation between reimbursement for ICU procedures and provider market share. Conversely, we observe a negative correlation with insurers' market share. Additionally, we document substantial variation in procedure prices, both across and within Brazilian states, and observe that more competitive markets in Brazil tend to have higher population and GDP levels. Overall, our research enhances our understanding of the price setting dynamics of physician reimbursement fees in the context of a developing country. The insights gained from this study can assist policymakers in formulating appropriate regulations to ensure appropriate access to healthcare services.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Brazilian National Health Insurance Agency (Agência Nacional de Saúde/ANS) but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of ANS. We will provide information to access its public version and all the code used to clean and obtain the results in the paper.

Notes

Agência Nacional de Saúde Suplementar. http://www.ans.gov.br/perfil-do-setor/dados-e-indicadores-do-setor/d-tiss-detalhamento-dos-dados-do-tiss.

Conselho Federal de Medicina. “Resolução CFM No 1.673/2003”. https://sistemas.cfm.org.br/normas/visualizar/resolucoes/BR/2003/1673.

Agência Nacional de Saúde Suplementar. http://www.ans.gov.br/perfil-do-setor/dados-e-indicadores-do-setor/d-tiss-detalhamento-dos-dados-do-tiss.

Agência Nacional de Saúde Suplementar. http://www.ans.gov.br/perfil-do-setor/dados-e-indicadores-do-setor/d-tiss-detalhamento-dos-dados-do-tiss.

IBGE. Produto Interno Bruto Dos Municípios. https://www.ibge.gov.br/estatisticas/economicas/contas-nacionais/9088-produto-interno-bruto-dos-municipios.html.

Hospital consultations included daily ICU consultant ward rounds per patient (TISS code 10,104,011); 12-h, on-site, ICU intensivist shifts per patient (TISS code 10,104,020); hospital consultations (TISS code 10,102,019); newborn appointments in the baby nursery (TISS code 10,103,015); and newborn appointments in the delivery room (TISS code 10,103,023).

Refer to the Appendix for ICU consultant results by different market concentrations.

In the Brazilian private health care sector, hospitals typically hire doctors through medical associations, which are firms comprising a group of doctors. These associations play a crucial role in minimizing transaction costs, payroll taxes, and strengthening the bargaining power of healthcare providers. As a result, the fixed effects of providers usually pertain to medical associations rather than to individual doctors. In addition, each specific area inside a hospital (such as the ICU) is typically associated with a single or a few medical associations. Therefore, we hope that incorporating the provider ID in our specifications helps minimize this limitation.

The unidentified version of this database can be found at http://ftp.dadosabertos.ans.gov.br/FTP/PDA/TISS/HOSPITALAR/

Note that we are not working with the consolidated version of the database (suffix _CONS), in which ANS organizes the information at the event level, but with the version that contains all procedures performed in an event (suffix _DET).

Price setting studies in healthcare markets usually consider the full event as the unit of analysis. This is adequate since providers may strategically differ in the quantity and composition of healthcare inputs used to tackle the same diagnosis and form their prices. For most episodes, insurers pay for medical fees, exams and diagnosis tests, medical supplies, surgical equipment, and daily hospitalizations costs. In TISS, insurance companies fill different forms depending on the service provided, which makes it difficult to fully recover the payment for all inputs. Therefore, the analysis of prices related to healthcare episodes was not possible in this study. We chose to focus on physician hospital visits, since the only costs related to these procedures are medical fees.

Before trimming the bottom and top 2.5% price values, we also deleted the cases in which we had less than 100 observations per state/procedure. This amounted to only 494 observations.

References

Agirdas, C., Krebs, R. J., & Yano, M. (2019). The effects of competition on premiums: Using United Healthcare’s 2015 entry into affordable care Act’s marketplaces as an instrumental variable. Health Economics, Policy and Law, 14(3), 374–399. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1744133117000263

Almeida, S., Azevedo, P. (2010). Cooperativas Médicas: Ilícito, Antitruste Ou Ganho de Bem-Estar? Textos Para Discussão Da Escola de Economia de São Paulo Da Fundação Getulio Vargas. https://bibliotecadigital.fgv.br/dspace/handle/10438/6894

Andrade, M. V., Maia, A. C., Lima, H., & Carvalho, L. (2015). Estrutura de Concorrência No Setor de Operadoras de Planos de Saúde No Brasil. Agência Nacional de Saúde.

Atos de Concentração nos mercados de planos de saúde, hospitais e medicina diagnóstica. Cadernos do Cade, 2018. Brasilia, DF. https://cdn.cade.gov.br/Portal/centrais-de-conteudo/publicacoes/estudos-economicos/cadernos-do-cade/DOI/Cadernos-do-Cade_ACs-nos-mercados-de-planos-de-saude_DOI_10.52896_dee.cc1.018.pdf

Austin, D. R., & Baker, L. C. (2015). Less physician practice competition is associated with higher prices paid for common procedures. Health Affairs, 34(10), 1753–1760. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0412

Baker, L. C., Kate Bundorf, M., Royalty, A. B., & Levin, Z. (2014). Physician practice competition and prices paid by private insurers for office visits. JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association, 312(16), 1653–1662. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2014.10921

Boozary, A. S., Feyman, Y., Reinhardt, U. E., & Jha, A. K. (2019). The association between hospital concentration and insurance premiums in ACA marketplaces. Health Affairs, 38(4), 668–674. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05491

Burgess, J. F., Carey, K., & Young, G. J. (2005). The effect of network arrangements on hospital pricing behavior. Journal of Health Economics, 24(2), 391–405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2004.10.002

CADE, Conselho Administrativo de Defesa Econômica. 2008. “Guia Para Análise De Atos De Concentração Horizontais. pp. 1–43

Conselho Federal de Medicina (n.d.) Resolução CFM No 1.673/2003.” Accessed October 6, 2021b. https://sistemas.cfm.org.br/normas/visualizar/resolucoes/BR/2003/1673

Conselho Federal de Medicina. n.d. “Resolução CFM No 1.673/2003.” Accessed October 7, 2021a. https://sistemas.cfm.org.br/normas/visualizar/resolucoes/BR/2003/1673

Cooper, Z., Craig, S. V., Gaynor, M., & Van Reenen, J. (2019). The price ain’t right? Hospital prices and health spending on the privately insured. The Quartely Journal of Economics, 1, 51–107. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjy020.Advance

Dafny, L. S. (2010). Are health insurance markets competitive? American Economic Review, 100(4), 1399–1431. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.100.4.1399

Dafny, L., Duggan, M., & Ramanarayanan, S. (2012). Paying a premium on your premium? Consolidation in the US Health Insurance Industry. American Economic Review, 102(2), 1161–1185. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.102.2.1161

Dafny, L., Ho, K., & Lee, R. S. (2019). The price effects of cross-market mergers: Theory and evidence from the hospital industry. RAND Journal of Economics, 50(2), 286–325. https://doi.org/10.1111/1756-2171.12270

Dranove, D., Shanley, M., & Simon, C. (1992). Is hospital competition wasteful? The Rand Journal of Economics, 23(2), 247–262.

Fulton, B. D. (2017). Health care market concentration trends in the United States: Evidence and policy responses. Health Affairs, 36(9), 1530–1538. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0556

Gaynor, M., Ho, K., & Town, R. (2015). The industrial organization of health-care markets. Journal of Economic Literature, 53(2), 235–284. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.53.2.235

Gaynor, M., & Town, R. J. (2011). Competition in health care markets. Handbook of health economics (Vol. 2). Amsterdam: Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-53592-4.00009-8

Gaynor, M. S., Vogt, W. B., & Antwi, Y. A. (2009). A Bargain at twice the price? California hospital prices in the New Millennium. Forum for Health Economics & Policy. https://doi.org/10.2202/1558-9544.1144

Ghiasi, A., Zengul, F., Ozaydin, B., Oner, N., Breland, B. (2017). The impact of hospital competition on strategies and outcomes of hospitals: A systematic review of the U.S. Hospitals 1996–2016. Journal of Health Care Finance 44(2), 22–42.

Gowrisankaran, G., Nevo, A., & Town, R. (2015). Mergers when prices are negotiated: Evidence from the hospital industry. American Economic Review, 105(1), 172–203. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20130223

Gravelle, H., Scott, A., Sivey, P., & Yong, J. (2016). Competition, prices and quality in the market for physician consultations. The Journal of Industrial Economics, 64(1), 135–169. https://doi.org/10.1111/joie.12098

Halbersma, R. S., Mikkers, M. C., Motchenkova, E., & Seinen, I. (2011). Market structure and hospital-insurer bargaining in the Netherlands. European Journal of Health Economics, 12(6), 589–603. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-010-0273-z

Ho, K., & Lee, R. S. (2017). Insurer competition in health care markets. Econometrica, 85(2), 379–417. https://doi.org/10.3982/ecta13570

Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. (2019). Conta-Satélite de Saúde: Brasil, 2010–2017. vol. 71. https://biblioteca.ibge.gov.br/visualizacao/livros/liv101690_notas_tecnicas.pdf

Mendes, S. F., Rotzsch, J., Dias, R., Figueiredo, C., Góes, P., Werneck, H., Vieira, L. E., & Winter, A. (2009). An analysis of the implementation of the standard exchange of information in the health insurance market in Brazil. Journal of Health Informatics, 1(2), 61–67.

Mossialos, E., Djordjevic, A., Osborn, R., & Sarnak, D. (2016) International profiles of health care systems. The Commonwealth Fund. https://doi.org/10.26099/xp8v-kz31

Muhlestein, B. D., & Smith, N. J. (2016). Physician consolidation: Rapid movement from small to large group practices, 2013–15. Health Affairs, 35(9), 1638–1642.

Paim, G. B. (2010). Implementation of the fifth edition CBHPM. Jornal Vascular Brasileiro, 9(3), 118–210. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1677-54492010000300003

Paim, J., Travassos, C., Almeida, C., Bahia, L., & MacInko, J. (2011). The Brazilian health system: History, advances, and challenges. The Lancet, 377(9779), 1778–1797. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60054-8

Roberts, E. T., Chernew, M. E., & Michael McWilliams, J. (2017). Market share matters: Evidence of insurer and provider bargaining over prices. Health Affairs, 36(1), 141–148. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0479

Robinson, J. C., & Luft, H. S. (1985). The impact of hospital market structure on patient volume, average length of stay, and the cost of care. Journal of Health Economics, 4(4), 333–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-6296(85)90012-8

Roos, A. F., Croes, R. R., Shestalova, V., Varkevisser, M., & Schut, F. T. (2019). Price effects of a hospital merger: Heterogeneity across health insurers, hospital products, and hospital locations. Health Economics, 28(9), 1130–1145. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.3920

Scheffer, M., et al. (2018). Demografia Médica No Brasil 2018. Cremesp.

Scheffler, R. M., & Arnold, D. R. (2017). Insurer market power lowers prices in numerous concentrated provider markets. Health Affairs, 36(9), 1539–1546. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0552

Zwanziger, J., Melnick, G., & Bamezai, A. (1994). Costs and Price Competition in California Hospitals, 1980–1990. Health Affairs, 13(4), 118–126. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.13.4.118

Acknowledgements

Monica Viegas Andrade thanks the financial support received from the National Research Council (productivity scholarship #305592/2017-3), from Fapemig (Research Foundation of the State of Minas Gerais) and from Fundação Getúlio Vargas. Carolina Marinho thanks the financial support received from Insper Instituto de Ensino e Pesquisa, Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP—grant number: 2017/22023-3) and Fundação Getúlio Vargas. Letícia Nunes thanks the financial support received from Fundação Getúlio Vargas. The authors are thankful to Rafaela Nogueira for guidance and support during the project. To Daniel Nogueira for research assistant. To professors Rodrigo Soares, Sergio Firpo, Paulo Furquim, Renata Narita, Rudi Rocha, Naercio Menezes, Fabiana Rocha and Andre Portela for reading and comments.

Funding

This study was funded by the Fundação Getulio Vargas. The sponsor received periodical reports informing on the activities conducted and partial results. In addition, they received a final report with all the results of the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix

Data details

The National Health Agency established TISS (Troca de Informações na Saúde Suplementar) as a mandatory standard for the electronic exchange of healthcare data and expenditures between private health insurance companies and health providers. In this study, we used a confidential version of TISS received directly from NHA in 2018. It contains records of inpatient procedures delivered and financed by private health plans in Brazil, from July 2015 to December 2016.Footnote 9Footnote 10 More specifically, the data includes information related to the procedures performed (e.g. date, quantity, the amount paid to the provider), the patient (age, gender, and fake id), the insurer (company’ size and a fake id) and the provider (municipality and a fake id).

Even though sending this information to NHA is mandatory, we were concerned about TISS representativeness since we obtained its identified version for the first 18 months of existing records. We decided to exclude 2015 from the study and focus on 2016, the period for which we knew that the amount informed at TISS represented, on average, 64.5% of all private healthcare expenditures in the year (32).

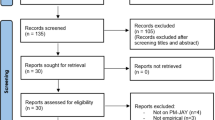

Our database started with 6,932,687 observations or 55,535,644 procedures performed in 2016. We kept only the procedures related to hospital medical visits: daily ICU consultant ward round per patient (TISS code 10104011); 12-h, on-site, ICU intensivist shift per patient (TISS code 10104020); hospital consultations (TISS code 10102019); newborn appointment in baby nursery (TISS code 10103015); and newborn appointment in the delivery room (TISS code 10103023). This amounted to 8,109,493 proceduresFootnote 11 in total.

Because TISS is an administrative database, imputation errors are present and must be addressed. To deal with these measurement errors, we trimmed the bottom and top 2.5% price values per state and procedure type.Footnote 12 After the removal of outliers, our final sample comprised 7,632,240 medical visits distributed among 723,503 users, 9180 providers, 499 insurance companies, and 1234 municipalities.

The price analysis focuses on the two types of ICU physician fees (TISS codes 10,104,011 and 10,104,020) for three reasons. First, the only costs related to these events are medical fees; therefore, there is no need to identify any additional items related to these reimbursement codes. In some circumstances, health providers may practice lower fees because they compensate for their receipts augmenting the quantity or prices of other charges (18). Second, the bargaining processes for ICU reimbursements are usually mediated by hospitals, and patients are not able to choose their preferred physician. Hence, we expect bilateral bargaining to be better assessed. Third, ICU fees do not vary by the type of room covered in the health plan (private vs. shared) or by time and weekdays of care, something that happens with the other procedures. In this manner, we assume that that the provider-insurer bargain is the main source of price variation. Table 3 displays, for each type of hospital medical consultation, the total quantity produced, and the total amount paid by health insurance companies to providers in 2016. In quantity terms, ICU visits represented 34% of all medical consultations. As for the value paid by health insurance companies, it amounts to 44%. When we compare the two ICU procedures, we see that the intensivist fee is the most representative, accounting for nearly 86% of all ICU medical reimbursement.

It is important to note that a provider in our dataset may be a physician or an association of physicians. Unfortunately, the identified version of TISS dataset made available by NHA does not detail information about the type of provider (corporate entity or individual), health insurance contract characteristics and neither allows identification of the hospital where the inpatient care occurred. Also, as TISS displays information regarding utilization, only users that were hospitalized, and not all beneficiaries of health plans, are inserted in the analysis.

Besides the TISS, other publicly available datasets were also used to obtain socioeconomic information at the local level. Data for private health insurance coverage for each municipality were obtained from the NHA website (24); population projections for each Brazilian municipality and the per capita Gross Domestic Product were obtained from the Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (35–36).

Empirical strategy and results

The following section explains how the market shares and HHI were defined and details the regression model used to produce Exhibits 3 and 4 in the main text, together with their results.

Relevant market, market share and HHI

One challenge of antitrust analysis is the definition of the relevant market. The product dimension is determined by the procedure itself, so our defiance is the definition of the geographic market. Since we are investigating only medical reimbursement codes during hospitalizations, it is reasonable to consider that the geographic market for these procedures is local and determined by doctors' availability to displace to deliver inpatient care. In our database, the only available information regarding the geographic market is the provider's municipality. In this context, one ideal definition of a geographic market should consider a maximum radius of displacement and then include all municipalities inside this area (9, 11). Some difficulties arise with this definition, specifically in Brazil. Firstly, it is hard to uniquely define a parameter for the radius definition since Brazil presents a large heterogeneity in terms of population density and urbanization. Secondly, some municipalities could not be totally inside the area determined by the radius and might belong to more than one market.

In this paper, we considered the geopolitical boundaries of Brazilian municipalities as the geographic definition of the relevant market. Since we are analyzing only ICU procedures, our sample encompasses only municipalities that have hospitals with ICU units and private users. Because of that, although our geographic markets are municipalities, we are working with larger and more populated areas. This definition also accords well with the literature, especially for the United States, where many papers consider geopolitical boundaries to define the geographical market (10), (11), (12), (13), (14), (15), (20), (21). Table 4 displays the characteristics of the relevant markets for both the Southeast region (considered in the regression models) and the entire country.

The market shares are computed for both providers and health insurance companies in each geographical market. It considers their participation in the total number of medical procedures in each municipality per year. The HHI was estimated for both insurance companies and provider markets. According to the Brazilian Administrative Council for Economic Defense (CADE) and the U.S. Department of Justice, an HHI of less than 1500 represents an industry with low market concentration; an HHI ranging between 1500 and 2500 represents moderate concentration; and HHI values of more than 2500 represent a highly concentrated industry.

Regression model and results

We estimated linear regression models with fixed effects to analyze the association between procedure prices and market competition. We considered the 2016 monthly data for the Brazilian Southeast region, which comprises the majority of private health insurance contracts in Brazil. Our variables of interest are the market share of both providers and insurance companies. Three main specifications were estimated for each ICU procedure, with the dependent variable being the natural log of the reimbursement fee.

In all three models, we included month and market fixed effects. Month fixed effects are important in accounting for price adjustments between health insurance and providers that only occur once a year. Market fixed effects were included to account for socioeconomic heterogeneity and the differences in the management of health care services in SUS that may affect opportunity costs for private health providers. The inclusion of market fixed effects also captures other crucial market characteristics, including both the providers’ and insurers’ HHI. Our specifications cluster standard errors at the municipality level to account for the heteroscedastic and serially correlated errors.

In the first specification, or the provider’s model, we analyzed the relationship between the provider's market share and the ICU medical reimbursement fees, controlling for insurance companies fixed effects. The inclusion of health insurance fixed effects allows us to capture the variation in procedure prices that arises from different providers, each with different market shares, bargaining with the same health insurance company. This means that health insurance companies’ time-invariant characteristics, such as size, market share, and overall quality were accounted for in the model. Specifically, we estimated the following regression:

\(Ln\left({P}_{ihmt}\right)\): reimbursement fee received by provider i from health insurance company h in market m during month t; \({S}_{im}\): market share of provider i in market m; \({\tau }_{h}\): health insurance company fixed effects; \({\lambda }_{m}\): market fixed effect;\({\phi }_{t}\): month fixed effect.

In the second specification, or the insurers' model, we focused on the association between insurance companies' market shares and the ICU medical reimbursement fees, controlling for providers' fixed effects. The variable of interest captures the variation in procedure prices due to different insurance companies bargaining with the same provider. Therefore, provider characteristics stable throughout the year, including overall quality, are controlled for in the model. More specifically, the regression estimated was:

\(Ln\left({P}_{ihmt}\right)\): reimbursement fee received by provider i from health insurance company h in market m during month t; \({S}_{hm}\): market share of health insurance company h in market m; \({\mu }_{i}\): provider fixed effects; \({\lambda }_{m}\): market fixed effect; \({\phi }_{t}\): month fixed effect.

The advantage of estimating separate models (the first and second specifications) is the inclusion of provider fixed effects (in the insurers model) and insurer fixed effects (in the providers model) in the regressions. The fixed effects of both insurers and providers are crucial to our analysis. They are used to control for differences in time-invariant non observable characteristics that could affect both shares and prices, including the quality of these players. The use of these fixed effects significantly reduces the potential bias of omitted variables in our results.

Additionally, the bargaining process between health agents may vary depending on the size of the counterpart market. To account for this heterogeneity, we conducted an additional analysis by re-estimating both the provider and insurer models for different subsamples. These subsamples were based on three levels of concentration indices (HHI) that corresponded to the counterpart player in the bargaining process. This approach allowed us to gain further insights into the dynamics of the bargaining process in different market contexts.

In the final specification, we adapted the model proposed by Halbersma et al. (2011) to our specific context and available data. We aimed to jointly estimate the relationship of health insurance and provider market shares with prices. We directly regressed reimbursement fees on the market shares of both providers and health insurance companies. Unfortunately, due to data variability constraints, we were unable to include all fixed effects in this model. Instead, we included the provider fixed effect, which captures the many provider-level information considered in Halbersma et al. (2011). This integrated or combined model allows us to analyze the association between market shares and prices in a more comprehensive manner. The model specification is described below:

\(Ln\left({P}_{ihmt}\right)\): reimbursement fee received by provider i from health insurance company h in market m during month t; \({S}_{im}\): market share of provider i in market m; \({S}_{hm}\): market share of health insurance company h in market m; \({\mu }_{i}\): provider fixed effects; \({\lambda }_{m}\): market fixed effect; \( {\phi }_{t}\): month fixed effect.

Table 5 displays the regression results shown in Exhibit 3 in the paper, together with their F-statistic and R-squared.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Andrade, M.V., Marinho, C., Nunes, L. et al. Price setting in the Brazilian private health insurance sector. Int J Health Econ Manag. 24, 57–80 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10754-023-09361-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10754-023-09361-0