Abstract

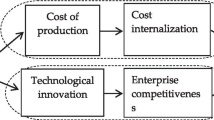

Prior studies obtained mixed conclusions on the relationship between firm exporting and pollution emissions, probably because the role of environmental regulation has been ignored in this relationship. This study focuses on whether the abatement effect of exporting is related to the stringency of environmental regulation. To avoid measurement bias in the environmental regulation stringency faced by firms, we use the two control zones policy implemented in China to reduce sulfur dioxide (SO2) emissions as a natural experiment to distinguish the difference in the SO2 regulation stringency faced by different firms. Empirical results show that Chinese manufacturing firms can significantly reduce their SO2 emissions intensity by exporting, but the abatement effect of exporting occurs only in the firms regulated by the two control zones policy. This result confirms for the first time that the abatement effect of exporting stems from the incentives of stringent environmental regulations. Further analysis shows that the abatement effect of exporting is realized mainly through firm investment in source control technologies rather than in end-of-pipe treatment technologies. The findings of this study suggest that stringent environmental regulations are important for emerging and developing countries to achieve environment-friendly exports.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Some or all data, models and/or code generated or used during the study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Notes

A region is included in an SO2 pollution control zone if (1) the annual average concentration of SO2 in its environment exceeded the national secondary standard in recent years, (2) the daily average concentration of SO2 in its environment exceeds the national tertiary standard (i.e., 250 μg/m3), or (3) its SO2 emissions are significant. A region is included in an acid rain control zone if (1) the average value of potential of hydrogen in its precipitation is equal to or less than 4.5, (2) its sulfate deposition exceeds the critical load, or (3) its SO2 emissions are large. For details, see https://www.mee.gov.cn/.

The TCZs policy focuses on controlling SO2 emissions from coal combustion using comprehensive prevention and control measures combining industrial restructuring, energy conservation, and consumption reduction, changing the urban energy structure, promoting clean production, and eliminating outdated processes and equipment with end-of-pipe treatment.

In the literature on the relationship between firm exporting and firm economic performance, scholars used different methods to test how exporting benefits firms. So far however, there remains to be a unified conclusion on which method is better. For example, Chang & Chung (2017) used several methods examined learning-by-exporting hypothesis, and pointed out that “Since each approach is based on its own theoretical assumptions and data requirements, we cannot say whether one approach is superior. Rather, each approach is best suited to particular settings, data, and phenomena”.

The value added is deflated by the industry-level (four-digit Chinese industry classification) producer price index. The addition of one before the logarithm is taken is performed to retain the firms with zero SO2 emissions in the study sample. However, regardless of the environmental regulation stringency for SO2 emissions, the firms with no SO2 emissions have no incentive to reduce such emissions. Therefore, in the robustness tests, the firms with no SO2 emissions are removed from the sample.

The Sargan–Hansen test is as a generalized test for over-identifying restrictions between fixed and random effects of a panel data model, which is generated in STATA using the—xtoverid—command. Unlike the Hausman version, the xtoverid enabled us to use the coefficients of the cluster-robust panel regression.

Fixed assets are deflated by the fixed asset price index.

Lin (2015) compared the annual growth rate of the Baltic Dry Index with the growth in average exports volume for China’s exporters and found that the growth (decline) in the Baltic Dry Index is at times accompanied by a slowdown (expansion) in exports over the period from 1999 to 2007.

Lin & Sim (2013) showed that country groups, such as the least developed countries, are insignificant in driving the Baltic Dry Index, let alone a firm.

The sample includes only firms with more than three years of records between 2000 and 2007 to avoid estimation bias owing to the short observation period.

\({S}_{i,0}=(sal{e}_{i,0}-\mathit{min}\_sal{e}_{i\in j,0})/(\mathit{max}\_sal{e}_{i\in j,0}-\mathit{min}\_sal{e}_{i\in j,0}),{S}_{i,0}\in ({0,1}]\), where \(sal{e}_{i,0}\) is the total sales of firm i in the base year, and \(\mathit{max}\_sal{e}_{i\in j,0}\) and \(\mathit{min}\_sal{e}_{i\in j,0}\) are the maximum and minimum total sales of the firms in industry j (the two-digit industry to which firm i belongs) in the base year, respectively. The base year is set to 1999.

Lin (2015) use \({\theta }_{i,0}\times \text{ln}(BD{I}_{t-1})\) as an instrumental variable for the export value of Chinese firms during the period of 2000–2007. Since existing research suggested that the sunk costs of firms to enter export markets are high, and firms with considerable capacity can effectively bear the fixed costs of exporting (Melitz, 2003), we modify the instrumental variable in Lin (2015) by adding the multiplier \({S}_{i,0}\).

Integrated prevention and control measures for acid rain and SO2 emissions in TCZs mainly include (1) reducing the sulfur content of coal, (2) controlling SO2 emissions from thermal power plants, (3) controlling SO2 emissions from boilers, (4) controlling SO2 emissions from industrial furnaces, (5) strengthening the construction of urban energy infrastructure to control domestic SO2 emissions, and (6) controlling SO2 emissions from various processes. See https://www.mee.gov.cn/gkml/zj/wj/200910/t20091022_172128.htm for details.

For example, if more zero-emissions firms are distributed in NTCZs than in TCZs, then observing the abatement effect of exporting in the NTCZs may be difficult.

PSM-DID is generally used in studies on the relationship between firms’ export strategies and economic performance.

To calculate the emissions intensity changes in the treatment group before and after exporting (see the first item in brackets in Equation [5]), we must include the firms with continuous observations (i.e., the emissions data and export status can be observed year by year) and an export status changing from 0 to 1 into the treatment group. However, owing to the data structure problem, the number of firms meeting the above conditions is limited. For example, some firms start to export in year t, but their emissions data in year t-1 or year t are missing. We can observe the emissions data in the second and third years after exporting for only a few firms. Therefore, to accurately estimate and alleviate the estimation error caused by the small sample size, we keep the observation in the year when the firm starts to export and the observation in the previous year of exporting and use PSM-DID to analyze the short-term effects of exporting on SO2 emissions intensity.

References

Alesina, A., & Zhuravskaya, E. (2011). Segregation and the quality of government in a cross section of countries. American Economic Review, 101(5), 1872–1911.

Bai, X., Hong, S., & Wang, Y. (2021). Learning from processing trade: Firm evidence from China. Journal of Comparative Economics, 49(2), 579–602.

Banerjee, S. N., Roy, J., & Yasar, M. (2021). Exporting and pollution abatement expenditure: Evidence from firm-level data. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 105, 102403.

Bartik, T. J. (1988). The effects of environmental regulation on business location in the United States. Growth and Change, 19(3), 22–44.

Batrakovay, S., & Davies, R. B. (2012). Is there an environmental benefit to being an exporter? Evidence from firm level data. Review of World Economics, 148, 449–474.

Baum, C. F., Schaffer, M. E., & Stillman, S. (2007). Enhanced routines for instrumental variables/generalized method of moments estimation and testing. The Stata Journal, 7(4), 465–506.

Becker, R. A. (2011). Local environmental regulation and plant-level productivity. Ecological Economics, 70(12), 2516–2522.

Berry, H., Kaul, A., & Lee, N. (2021). Follow the smoke: The pollution haven effect on global sourcing. Strategic Management Journal, 42(13), 2420–2450.

Cai, X., Lu, Y., Wu, M., et al. (2016). Does environmental regulation drive away inbound foreign direct investment? Evidence from a quasi-natural experiment in China. Journal of Development Economics, 123, 73–85.

Chang, S., & Chung, J. (2017). A quasi-experimental approach to the multinationality-performance relationship: An application to learning-by-exporting. Global Strategy Journal, 7(3), 257–285.

Cherniwchan, J., Copeland, B. R., & Taylor, M. S. (2017). Trade and the environment: New methods, measurements, and results. Annual Review of Economics, 9(1), 59–85.

Cinelli C, Forney A, Pearl J. A crash course in good and bad controls. Sociological Methods & Research, 2022, 41652256.

Cui, J., Lapan, H., & Moschini, G. (2016). Productivity, export, and environmental performance: Air pollutants in the United States. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 98(2), 447–467.

Cui, J., & Qian, H. (2017). The effects of exports on facility environmental performance: Evidence from a matching approach. Journal of International Trade and Economic Development, 26(7), 759–776.

Cui, J., Lapan, H. E., & Moschini G. (2012). Are exporters more environmentally friendly than non-exporters theory and evidence. Economics Working Papers (2002–2016), 77.

Dardati, E., & Saygili, M. (2021). Are exporters cleaner? Another look at the trade-environment nexus. Energy Economics, 95, 105097.

De Loecker, J. (2007). Do exports generate higher productivity? Evidence from slovenia. Journal of International Economics, 73(1), 69–98.

Del Río, G. P. (2005). Analysing the factors influencing clean technology adoption: A study of the Spanish pulp and paper industry. Business Strategy and the Environment, 14(1), 20–37.

Eliasson, K., Hansson, P., & Lindvert, M. (2012). Do firms learn by exporting or learn to export? Evidence from small and medium-sized enterprises. Small Business Economics, 39(2), 453–472.

Forslid, R., Okubo, T., & Ulltveit-Moe, K. H. (2018). Why are firms that export cleaner? International trade, abatement and environmental emissions. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 91, 166–183.

Frondel, M., Horbach, J., & Rennings, K. (2007). End-of-pipe or cleaner production? An empirical comparison of environmental innovation decisions across OECD countries. Business Strategy and the Environment, 16(8), 571–584.

Goldar B, Goldar A. Impact of export intensity on energy intensity in manufacturing plants: Evidence from India. The Journal of International Trade & Economic Development, 2022, ahead-of-print, 1–26.

Greenstone, M., & Jack, B. K. (2015). Envirodevonomics: A research agenda for an emerging field. Journal of Economic Literature, 53(1), 5–42.

Gutiérrez, E., & Teshima, K. (2018). Abatement expenditures, technology choice, and environmental performance: Evidence from firm responses to import competition in mexico. Journal of Development Economics, 133, 264–274.

He, L., & Huang, G. (2020). Processing trade and energy efficiency: Evidence from Chinese manufacturing firms. Journal of Cleaner Production, 276, 122507.

He, L., & Huang, G. (2021). How can export improve firms’ energy efficiency? The role of innovation investment. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 59, 90–97.

Heckman, J. J., Ichimura, H., & Todd, P. (1998). Matching as an econometric evaluation estimator. The Review of Economic Studies, 65(2), 261–294.

Holladay, J. S. (2016). Exporters and the environment. The Canadian Journal of Economics, 49(1), 147–172.

Hu, C., Lin, F., & Wang, X. (2016). Learning from exporting in China. Economics of Transition, 24(2), 299–334.

Kreickemeier, U., & Richter, P. M. (2014). Trade and the environment: The role of firm heterogeneity. Review of International Economics, 22(2), 209–225.

Levinsohn, J., & Petrin, A. (2003). Estimating production functions using inputs to control for unobservables. The Review of Economic Studies, 70(2), 317–341.

Lin, F. (2015). Learning by exporting effect in China revisited: An instrumental approach. China Economic Review, 36, 1–13.

Lin, F., & Sim, N. C. S. (2014). Baltic dry index and the democratic window of opportunity. Journal of Comparative Economics, 42(1), 143–159.

Lin, F., & Sim, N. C. (2013). Trade, income and the Baltic dry index. European Economic Review, 59, 1–18.

Liu, B. J. (2017). Do bigger and older firms learn more from exporting? Evidence from China. China Economic Review, 45, 89–102.

Liu Y, Zhang X. Environmental regulation, political incentives, and mortality in China. European Journal of Political Economy, 2022, 102322.

Ma, H., Qiao, X., & Xu, Y. (2015). Job creation and job destruction in China during 1998–2007. Journal of Comparative Economics, 43(4), 1085–1100.

Melitz, M. J. (2003). The impact of trade on intra-industry reallocations and aggregate industry productivity. Econometrica, 71(6), 1695–1725.

Naoto, J., Hiroaki, S. (2015). Does exporting improve firms' CO2 emissions intensity and energy intensity? Evidence from Japanese manufacturing. RIETI Discussion Paper Series 15-E-130.

Pei, J., Sturm, B., & Yu, A. (2021). Are exporters more environmentally friendly? A re-appraisal that uses China’s micro-data. World Economy, 44(5), 1402–1427.

Qi, J., Tang, X., & Xi, X. (2021). The size distribution of firms and industrial water pollution: A quantitative analysis of China. American Economic Journal-Macroeconomics, 13(1), 151–183.

Rosenbaum, P. R., & Rubin, D. B. (1983). The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika, 70(1), 41–55.

Sahoo, B., Behera, D. K., & Rahut, D. (2022). Decarbonization: Examining the role of environmental innovation versus renewable energy use. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 29(32), 48704–48719.

Schaffer M, Stillman S. Xtoverid: Stata module to calculate tests of overidentifying restrictions after xtreg, xtivreg, xtivreg2, xthtaylor. 2016.

Staiger, D., & Stock, J. H. (1997). Instrumental variables regression with weak instruments. Econometrica, 65(3), 557–586.

Tanaka, S. (2015). Environmental regulations on air pollution in China and their impact on infant mortality. Journal of Health Economics, 42, 90–103.

Tang, H., Liu, J., & Wu, J. (2020). The impact of command-and-control environmental regulation on enterprise total factor productivity: A quasi-natural experiment based on China’s “two control zone” policy. Journal of Cleaner Production, 254, 120011.

Tran T M. Environmental benefit gain from exporting: evidence from Vietnam. World Economy, 2021.

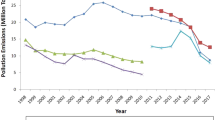

Xing, Z., Wang, J., Feng, K., et al. (2020). Decline of net so2 emission intensity in China’s thermal power generation: Decomposition and attribution analysis. Science of the Total Environment, 719, 137367.

Xu, C., Zhao, W., & Zhang, M., et al. (2021). Pollution haven or halo? The role of the energy transition in the impact of FDI on SO2 emissions. Science of The Total Environment, , 763.

Zeng, B., Zhu, L., & Yao, X. (2020). Policy choice for end-of-pipe abatement technology adoption under technological uncertainty. Economic Modelling, 87, 121–130.

Zhang, B., Chen, X., & Guo, H. (2018). Does central supervision enhance local environmental enforcement? Quasi-experimental evidence from China. Journal of Public Economics, 164, 70–90.

Zhang, Y., Cui, J., & Lu, C. (2020). Does environmental regulation affect firm exports? Evidence from wastewater discharge standard in China. China Economic Review, 61, 101451.

Acknowledgements

This paper was supported by the Science Foundation of Ministry of Education of China [grant number: 18XJA790008], and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities [grant number: JBK230117; JBK2307119].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

We declare that we do not have any commercial or associative interest that represents a conflict of interest in connection with the work submitted.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A

We conducted some tests to ensure that fixed effect estimation is appropriate for our models. The simple way to check for the fit of fixed effects model is to use the Hausman test to compare the standardized regression coefficients of the fixed effects model with those of the random effects model. However, the Hausman test does not allow for cluster-robust standard errors and thus could not control for the unobserved heterogeneity of firms. Hence, we used an alternative Hausman-like test (i.e., the xtoverid cluster test) to compare fixed vs. random effects (Schaffer & Stillman, 2016). Sargan–Hansen tests were performed following the specifications in Columns (4) to (6) of Table 2. The Sargan–Hansen test shows that the p-value of the Chi-square is less than 0.05, thereby indicating that the null hypothesis is rejected and that fixed effects estimator is an appropriate estimator for our regression models. Details can be found in Table

10.

Appendix B

Tables 11, 12, 13, 14 show the first- and second-stage regression results of the 2SLS estimation obtained through the Stata command xtivreg2. The estimation results of the first-stage regression in Tables 11, 12, 13 and 14 show that the coefficients of the instrumental variable BDIf are significantly negative, thereby indicating that the higher the Baltic Dry Index faced by firms, the lower their likelihood of exporting. This outcome is consistent with our expectation of the negative effect of the Baltic Dry Index on firms’ export decisions owing to trade costs.

Appendix C

See Table 15.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Cheng, R., Yuan, P. & Li, H. Abatement effect of exporting and environmental regulation stringency: evidence from a natural experiment in China. Environ Dev Sustain (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-023-03564-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-023-03564-8