Abstract

We investigate the impact of bank market power on the interest rates charged for loans to nonfinancial firms within the context of a developing country. Employing a distinctive amalgamation of data encompassing banks, firms, and loan specifics, alongside panel data fixed-effect models, we elucidate that banks wielding greater market power tend to impose higher interest rates on their loan products. This effect becomes more pronounced for banks positioned at the upper echelons of the market power spectrum (relative market power) and in instances of lengthier credit relationships. However, its severity can be mitigated for firms managing multiple credit connections (subjective market power). Our findings shed light on the presence of practices aimed at extracting economic rents and accentuate the substantial costs associated with changing lending partners in the corporate credit landscape. Various papers have delved into the empirical examination of how competition impacts the accessibility and expenses tied to bank credit for nonfinancial firms, yielding a mosaic of outcomes. Our contribution to this body of the literature manifests as a more incisive empirical analysis, enabling us to disentangle the opposing dynamics at play. This analytical depth is achievable solely due to the exceptional dataset we have curated. Significantly, our study stands out as one of the initial endeavors to interlink dynamic, bank-level gauges of market power with directly observed interest rates at the firm level, all while controlling for bank and loan-specific characteristics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The greatest difficulty for finding a causal relation in this paper comes from the fact that there may be unobserved determinants of commercial loan interest rates that covary with banks’ measured market power. If present, these determinants are most likely to be related to unobserved demand effects, something we control for in Sect. 4 with the inclusion of firm-fixed effects.

We compute the dependent variable this way following the literature on relationship lending. Alternatively, the real interest rate on each loan was used, obtaining qualitatively identical results.

The length of a credit relationship is computed as the difference between the date of loan l, and the period in which the firm-bank pair appeared for the first time in the loan-level dataset. This may imply left-censoring for the length of some relationships which may have been established before the initial date of our dataset. However, left-censoring itself does not constitute a source of estimation bias. It would be troublesome only in the case in which the longest relationships, those which are left-censored, would be biased toward banks with a particularly high (or low) level of market power. But there is no reason to believe this is the case in our dataset.

Additional descriptive statistics such as means by market power quartiles are presented.

All figures here and in what follows are expressed in USD at 2020 current exchange rates.

In order to check for the potential effect of left-censoring of the relationship-length variable we include estimation results using a shorter period (2012–2019) in Appendix D. Main results do not vary with the trimming of the data which confirms our hypothesis that left-censoring is not an issue in our data.

References

Alvarez R, Jara M (2016) Banking competition and firm-level financial constraints in Latin America. Emerg Mark Rev 28(C):89–104

Batrancea L, Rathnaswamy MK, Batrancea I (2021) A panel data analysis on determinants of economic growth in seven non-bcbs countries. J Knowl Econ 13(2):1651–1665

Batrancea L, Rathnaswamy MK, Rus M-I, Tulai H (2022) Determinants of economic growth for the last half of century: a panel data analysis on 50 countries. J Knowled Econ. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-022-00944-9

Batrancea LM, Balci MA, Chermezan L, Akguller O, Masca ES, Gaban L (2022) Sources of smes financing and their impact on economic growth across the European union: Insights from a panel data study spanning sixteen years. Sustainability 14(22):15318

Beck T, Demirguc-Kunt A, Maksimovic V (2004) Bank competition and access to finance: international evidence. J Money, Credit, Bank 36(3):627–48

Berger A, Hannan T (1989) The price-concentration relationship in banking. Rev Econ Stat 71(2):291–99

Boone J (2008) A new way to measure competition. Econ J 118(531):1245–1261

Cañón C, Córtes E, Guerrero R (2022) Bank competition and the price of credit: Evidence using mexican loan-level data. Int Rev Econ Financ 79:56–74

Carbo-Valverde S, Rodríguez-Fernández F, Udell G (2009) Bank market power and sme financing constraints. Review of Finance 13(2):309–340

Casu B, Girardone C (2009) Testing the relationship between competition and efficiency in banking: A panel data analysis. Econ Lett 105(1):134–137

Claessens S, Laeven L (2004) What drives bank competition? Some international evidence. J Money, Credit, Bank 36(3):563–583

Clerides S, Delis MD, Kokas S (2015) A new data set on competition in national banking markets. Finan Markets, Instit Instr 24(2–3):267–311

Elzinga KG, Mills DE (2011) The Lerner index of monopoly power: origins and uses. Am Econ Rev 101(3):558–64

Fernandez J, Maudos J, Perez F (2005) Market power in European banking sectors. J Finan Serv Res 27(2):109–137

Fungacova Z, Shamshur A, Weill L (2017) Does bank competition reduce cost of credit? Cross-country evidence from Europe. J Bank Finance 83(C):104–120

Gelos RG (2009) Banking spreads in Latin America. Econ Inq 47(4):796–814

Giocoli N (2012) Who invented the Lerner index? Luigi Amoroso, the dominant firm model, and the measurement of market power. Rev Ind Organ 41(3):181–191

Gómez-González JE, Reyes NR (2011) The number of banking relationships and the business cycle: new evidence from Colombia. Econ Syst 35(3):408–418

Greenbaum SI, Kanatas G, Venezia I (1989) Equilibrium loan pricing under the bank-client relationship. J Bank Finance 13(2):221–235

Haber S (2009) Why banks do not lend: The mexican financial system. In: Levy S, Walton M (Eds), No Growth without Equity? Inequality, interests, and competition in Mexico

Hainz C, Weill L, Godlewski C (2013) Bank competition and collateral: theory and evidence. J Financial Serv Res 44(2):131–148

Hauswald R, Marquez R (2006) Competition and strategic information acquisition in credit markets. Rev Finan Stud 19(3):967–1000

Koetter M, Kolari JW, Spierdijk L (2012) Enjoying the quiet life under deregulation? Evidence from adjusted Lerner indices for US banks. Rev Econ Stat 94(2):462–480

Kroszner RS, Strahan PE (1999) What drives deregulation? Economics and politics of the relaxation of bank branching restrictions. Q J Econ 114(4):1437–1467

Kysucky V, Norden L (2016) The benefits of relationship lending in a cross-country context: a meta-analysis. Manage Sci 62(1):90–110

Landes WM, Posner RA (1981) Market power in antitrust cases. Harv Law Rev 94(5):937–996

Leon F (2015) Does bank competition alleviate credit constraints in developing countries? J Bank Finance 57(C):130–142

Lerner AP (1934) The concept of monopoly and the measurement of monopoly power. Rev Econ Stud 1(3):157–175

Love I, Martinez Peria M (2015) How bank competition affects firms’ access to finance. World Bank Econ Rev 29(3):413–448

Love I, Martinez-Peria MS (2015) How bank competition affects firms’ access to Finance. World Bank Econ Rev 29(3):413–448

Marquez R (2002) Competition, adverse selection, and information dispersion in the banking industry. Rev Financial Stud 15(3):901–926

Menkhoff L, Suwanaporn C (2007) On the rationale of bank lending in pre-crisis Thailand. Appl Econ 39(9):1077–1089

Mester LJ (1996) A study of bank efficiency taking into account risk-preferences. J Bank Finance 20(6):1025–1045

Neumark D, Sharpe S (1992) Market structure and the nature of price rigidity: evidence from the market for consumer deposits. Q J Econ 107(2):657–680

Ornelas JRH, da Silva MS, Van Doornik BFN (2022) Informational switching costs, bank competition, and the cost of finance. J Bank Finance 138:106408

Panzar JC, Rosse JN (1987) Testing for monopoly equilibrium. J Ind Econ 35(4):443–56

Petersen MA, Rajan R (1995) The effect of credit market competition on lending relationships. Q J Econ 110(2):407–443

Ryan RM, O’Toole CM, McCann F (2014) Does bank market power affect SME financing constraints? J Bank Finance 49(C):495–505

Shaffer S, Spierdijk L (2017) Market power: competition among measures. 9

Sharpe SA (1990) Asymmetric information, bank lending, and implicit contracts: a stylized model of customer relationships. J Financ 45(4):1069–1087

Smirlock M (1985) Evidence on the (non) relationship between concentration and profitability in banking. J Money, Credit, Bank 17(1):69–83

Tabak BM, Fazio DM, Cajueiro DO (2012) The relationship between banking market competition and risk-taking: do size and capitalization matter? J Bank Finance 36(12):3366–3381

Tabak BM, Gomes GM, da Silva Medeiros M (2015) The impact of market power at bank level in risk-taking: the Brazilian case. Int Rev Financ Anal 40(C):154–165

van Leuvensteijn M, Sorensen CK, Bikker JA, van Rixtel AA (2013) Impact of bank competition on the interest rate pass-through in the euro area. Appl Econ 45(11):1359–1380

Wilson BJ, Reynolds SS (2005) Market power and price movements over the business cycle. J Ind Econ 53(2):145–174

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

For comments and suggestions we thank Thorsten Beck, Julian Caballero, Hans Degryse, Andrew Powell, Banjamin Tabak, Lars Norden, and seminar participants at Lehman College, EAFIT, Universidad de La Sabana, Banco de Mexico, Banco de la Republica and ICESI, the IDB “Workshop on Bank Competition in Latin America” (Washington, D.C., October 3rd, 2017), IFABS Porto Conference (2017), the 1st Colombian Economic Conference (2018), and the IDB-Banco Central do Brasil “International Workshop on the Cost of Credit” (Brasilia, November 26–27th, 2018). Laura C. Diaz, Juan A. Paez and Juan G. Salazar provided superb research assistance. Financial support by the IDB ESW-RG-K1342 is gratefully acknowledged.

Appendices

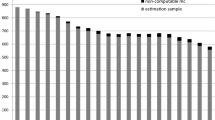

Appendix A: Mergers and acquisitions in the Colombian banking system

See Table 7.

Appendix B: Data sources, variable definitions and TOC estimation

1.1 Bank-level data

All of our bank-specific measures come from the financial supervisor in Colombia, Superintendencia Financiera. In particular, we access the excel workbooks provided by SuperFinanciera under the link https://www.superfinanciera.gov.co/publicacion/60776 (“Estados Financieros - Moneda total - COLGAAP”). These spreadsheets contain both balance sheet and income statement accounts. Our variable definitions are as follows:

-

Total bank assets: is taken as account number 100000 (“Activo”).

-

Fixed assets: is taken as account number 180000 (“Propiedades y equipos”).

-

Total bank investments: is taken as account number 130000 (“Inversiones”).

-

Equity: is taken as account number 300000 (“Patrimonio”).

-

Total bank net loans: is taken as account number 140000 (“Cartera de creditos y operaciones de leasing financiero“) which records net commercial, consumer, housing, and microcredit loans; and we exclude net financial leasing loans by subtracting account numbers for gross commercial, consumer, housing, and microcredit leasing loans (141183 to 141198; 141983 to 141998; 143283 to 143298; 143383 to 143398; 143683 to 143698; 144183 to 144198; 144283 to 144298; 144283 to 144498; 144583 to 144598; 145083 to 145098; 145983 to 145998; 146083 to 146098; 146283 to 146298; 146383 to 146398; 146583 to 146598; 146683-146698; 146783 to 146798; 146883 to 146898; 146983 to 146998; 147083 to 147098) and adding accounts for commercial, consumer, housing, and microcredit leasing provisions (149109, 149114, 149119, 149124, 149149, 149309, 149314, 149319, 149324, 149329, 149508, 149509, 149513, 149514, 149518, 149519, 149523, 149524, 149528, 149529, 149810).

-

Net Commercial loans: is the sum of account numbers 145900, 146000, 146200,146300 and 146500 to 147000 which record commercial loans under different risk categories (A to E) and using different collateral (“garantia idonea” and “otra garantia”); and exclude net commercial leasing loans by subtracting account numbers for gross commercial leasing loans (145983 to 145998; 146083 to 146098; 146283 to 146298; 146383 to 146398; 146583 to 146598; 146683-146698; 146783 to 146798; 146883 to 146898; 146983 to 146998; 147083 to 147098) and adding commercial leasing provisions (149508,149509,149513,149514,149518,149519,149523,149524,149528,149529).

-

Financial Income: is the sum of the account numbers for interest income (4102000), commissions (4115000), price level restatement (411015), return on investments (410403 + 410404 + 410405 + 410409 + 410421 + 410423 + 410424 + 4123000), dividends (414000), net profit in investment sales (4116000 + 4125000 – 5116000 – 5125000) investment valuation (410700 + 410800 + 410900 + 411100 + 411200 + 411300 – 510600 – 510800 – 510900 – 511100 – 511200 – 511400), other net financial income (410400 + 411005 + 412800 + 412900 – 410403 – 410404 – 410405 – 410409 – 410421 – 410423 – 410424 – 512800 – 512900), and net changes (413500 – 513500).

1.2 TOC estimation results

See Table 8.

Appendix C: Statistical tests

Figure 6 presents the correlation matrix plot between the variables included. Most of the variables do not present high significant correlations, ruling out concerns about multicollinearity. The unique variables that present high correlations are not included together into the regressions (i.e. Lerner index and Adjusted Lerner index).

Appendix D: Robustness checks

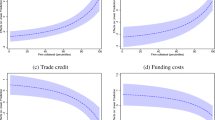

We trim our dataset to the period 2012–2019 in order to investigate whether our results are affected by the potential left-censoring of the relationship-lending variable. The results are presented in Table 9 and Fig. 7 below. Results are quantitatively similar to the ones observed in the main results of the document. This result help us to confirm our prior about the absence of left-censoring in our exercise.

Heterogeneous Effects of Bank Market Power (2012–2019). The figures plot marginal effects obtained using the coefficients from column 3 to 8 in Table 1

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Gomez-Gonzalez, J.E., Sanin-Restrepo, S., Tamayo, C.E. et al. Bank market power and firm finance: evidence from bank and loan-level data. Econ Change Restruct 56, 4629–4660 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10644-023-09570-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10644-023-09570-0