Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to examine the effects of an eight-session structured urban forest healing program for cancer survivors with fatigue.

Background

Cancer-related fatigue (CRF) is a complex and multifactorial common symptom among cancer survivors that limits quality of life (QoL). Although health benefits of forest healing on physiological, physical, and psychological aspect as well as on the immune system have been reported in many studies, there is limited evidence on the efficacy of specialized forest program for cancer survivors.

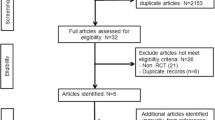

Method

A single-blinded, pre-test and post-test control group clinical trial was conducted with -75 cancer survivors assigned to either the forest healing group or the control group. The intervention was an eight-session structured urban forest program provided at two urban forests with easy accessibility. Each session consists of three or four major activities based on six forest healing elements such as landscape, phytoncides, anions, sounds, sunlight, and oxygen. Complete data of the treatment-adherent sample (≥ 6 sessions) was used to examine whether sociodemographic, clinical, physiological (respiratory function, muscle strength, balance, 6-min walking test) and psychological (distress, mood state, sleep quality, QoL) characteristics at baseline moderated the intervention effect on fatigue severity at 9 weeks.

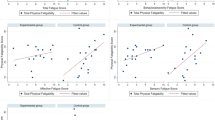

Results

Significant time-group interactions were observed muscle strength, balance, 6-min walking test, distress, fatigue, moods, and QoL. The mean difference in fatigue between pre- and post-forest healing program was 9.1 (95% CI 6.2 to 11.9), 11.9 (95% CI 7.6 to 16.1) in moods, and -93.9 (95% CI -123.9 to -64.0) in QoL, showing significant improvements in forest healing group, but no significant improvements in the control group.

Conclusion

This study suggests that a forest healing program positively impacts the lives of cancer survivors, by addressing both physical and psychological challenges associated with CRF.

Trial registration number

KCT0008447 (Date of registration: May 19, 2023)

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

The datasets generated during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Hofman M et al (2007) Cancer-related fatigue: the scale of the problem. Oncologist 12(S1):4–10

Andrykowski MA et al (2010) Prevalence, predictors, and characteristics of off-treatment fatigue in breast cancer survivors. Cancer 116(24):5740–5748

Carpenter JS et al (2004) Sleep, fatigue, and depressive symptoms in breast cancer survivors and matched healthy women experiencing hot flashes. In: Oncology nursing forum.

Bower JE et al (2014) Screening, assessment, and management of fatigue in adult survivors of cancer: an American Society of Clinical oncology clinical practice guideline adaptation. J Clin Oncol 32(17):1840

Yang S et al (2019) A narrative review of cancer-related fatigue (CRF) and its possible pathogenesis. Cells 8(7):738

Bower JE (2014) Cancer-related fatigue—mechanisms, risk factors, and treatments. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 11(10):597–609

Fabi A et al (2020) Cancer-related fatigue: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment. Ann Oncol 31(6):713–723

Fabi A et al (2017) The course of cancer related fatigue up to ten years in early breast cancer patients: What impact in clinical practice? Breast 34:44–52

Servaes P, Verhagen CA, Bleijenberg G (2002) Relations between fatigue, neuropsychological functioning, and physical activity after treatment for breast carcinoma: daily self-report and objective behavior. Cancer 95(9):2017–2026

Heo S, Heo N (2021) Influence of distress on fatigue among breast cancer patients: focusing on mediating effect of quality of life. J Korea Acad Ind 9:486–496

Seo JY, Yi M (2015) Distress and quality of life in cancer patients receiving chemotherapy. Asian Oncol Nurs 15(1):18–27

Institute, NC, 2015 Strategic Priorities Symptom Management & Quality of Life Steering Committee (SxQoL SC). 2015.

Yenson VM et al (2023) Defining research priorities and needs in cancer symptoms for adults diagnosed with cancer: an Australian/New Zealand modified Delphi study. Support Care Cancer 31(7):436

Mustian KM et al (2017) Comparison of pharmaceutical, psychological, and exercise treatments for cancer-related fatigue: a meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol 3(7):961–968

Minton O et al (2008) A systematic review and meta-analysis of the pharmacological treatment of cancer-related fatigue. J Natl Cancer Inst 100(16):1155–1166

Du S et al (2015) Patient education programs for cancer-related fatigue: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns 98(11):1308–1319

Duijts SF et al (2011) Effectiveness of behavioral techniques and physical exercise on psychosocial functioning and health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients and survivors—a meta-analysis. Psycho-oncology 20(2):115–126

Jacobsen PB et al (2007) Systematic review and meta-analysis of psychological and activity-based interventions for cancer-related fatigue. Health Psychol 26(6):660

Chae Y et al (2021) The effects of forest therapy on immune function. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(16):8440

Park S et al (2021) Physiological and Psychological Assessments for the Establishment of Evidence-Based Forest Healing Programs. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(17):9283

Rajoo KS, Karam DS, Abdullah MZ (2020) The physiological and psychosocial effects of forest therapy: A systematic review. Urban For Urban Green 54:126744

Song C et al (2019) Physiological and psychological effects of viewing forests on young women. Forests 10(8):635

Tsao T-M et al (2018) Health effects of a forest environment on natural killer cells in humans: An observational pilot study. Oncotarget 9(23):16501

Li Q et al (2010) A day trip to a forest park increases human natural killer activity and the expression of anti-cancer proteins in male subjects. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents 24(2):157–165

Han J-W et al (2016) The effects of forest therapy on coping with chronic widespread pain: Physiological and psychological differences between participants in a forest therapy program and a control group. Int J Environ Res Public Health 13(3):255

Ochiai H et al (2015) Physiological and psychological effects of a forest therapy program on middle-aged females. Int J Environ Res Public Health 12(12):15222–15232

Lee J et al (2011) Effect of forest bathing on physiological and psychological responses in young Japanese male subjects. Public Health 125(2):93–100

Park B-J et al (2009) Physiological effects of forest recreation in a young conifer forest in Hinokage Town, Japan. Silva Fenn 43(2):291–301

Park BJ et al (2010) The physiological effects of Shinrin-yoku (taking in the forest atmosphere or forest bathing): evidence from field experiments in 24 forests across Japan. Environ Health Prev Med 15:18–26

Choi J, Kim H (2017) The effect of 12-week forest walking on functional fitness and body image in the elderly women. J Kor Inst For Recreation 21:47–56

Lee M-M, Park B-J (2020) Effects of forest healing program on depression, stress and cortisol changes of cancer patients. J People Plants Environ 23(2):245–254

Nakau M et al (2013) Spiritual care of cancer patients by integrated medicine in urban green space: a pilot study. Explore 9(2):87–90

Choi YH, Ha YS (2014) The effectiveness of a forest-experience-integration intervention for community dwelling cancer patients' depression and resilience. J Korean Acad Community Health Nurs 25(2):109–118

Kim Y et al (2015) The influence of forest activity intervention on anxiety, depression, profile of mood states (POMS) and hope of cancer patients. J Kor Inst For Recreation 19(1):65–74

Kim H et al (2019) An exploratory study on the effects of forest therapy on sleep quality in patients with gastrointestinal tract cancers. Int J Environ Res Public Health 16(14):2449

Kim K (2020) Influence of forest healing programs on health care of cancer patients—Mainly about physiological characteristics and psychological traits. J Humenit Soc Sci 11:13–26

Park S et al (2021) Evidence-based status of forest healing program in South Korea. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(19):10368

Park EY, Song MK, Baek SY (2023) Analysis of Perceptions, Preferences, and Participation Intention of Urban Forest Healing Program among Cancer Survivors. Int J Environ Res Public Health 20(2):1604

Given B et al (2008) Establishing Mild, Moderate, and Severe Scores for Cancer-Related Symptoms: How Consistent and Clinically Meaningful Are Interference-Based Severity Cut-Points? J Pain Symptom Manage 35(2):126–135

Dauty M et al (2021) Reference values of forced vital capacity and expiratory flow in high-level cyclists. Life 11(12):1293

Mentiplay BF et al (2015) Assessment of Lower Limb Muscle Strength and Power Using Hand-Held and Fixed Dynamometry: A Reliability and Validity Study. PloS One 10(10):e0140822

Bandholm T et al (2011) Increased external hip-rotation strength relates to reduced dynamic knee control in females: paradox or adaptation? Scand J Med Sci Sports 21(6):e215–e221

Huang L et al (2022) Reliability and validity of two hand dynamometers when used by community-dwelling adults aged over 50 years. BMC Geriatr 22(1):580

O’Neal SK, Thomas J (2022) Relationship of single leg stance time to falls in Special Olympic athletes. Physiother Theory Pract:1–7

Schwiertz G, Beurskens R, Muehlbauer T (2020) Discriminative validity of the lower and upper quarter Y balance test performance: a comparison between healthy trained and untrained youth. BMC Sports Sci Med Rehabil 12(1):73

Bohannon RW et al (2015) Six-Minute Walk Test Vs. Three-Minute Step Test for Measuring Functional Endurance. J Strength Cond Res 29(11):3240–3244

Donovan KA et al (2022) NCCN Distress Thermometer Problem List Update. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 20(1):96–98

Okuyama T et al (2000) Development and validation of the cancer fatigue scale: a brief, three-dimensional, self-rating scale for assessment of fatigue in cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage 19(1):5–14

Lee H, Park EY, Sung JH (2023) Validation of the Korean Version of the Cancer Fatigue Scale in Patients with Cancer. Healthcare (Basel) 11(12)

Yeun EJ, Shin-Park KK (2006) Verification of the profile of mood states-brief: cross-cultural analysis. J Clin Psychol 62(9):1173–1180

McNair D, Lorr M, Droppelman L (1978) Manual profile of mood states. San Diego, CA: Educational and Industrial Testing Service; 1971. Ilfeld FW Jr: Psychologic status of community residents along major demographic dimensions. Arch Gen Psychiatry 35:71

Shin S, Kim SH (2020) The reliability and validity testing of Korean version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. J Converg Inf Technol 10(11):148–155

Buysse DJ et al (1989) The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res 28(2):193–213

Fayers P et al (1995) EORTC QLQ–C30 scoring manual. European Organisation for research and treatment of cancer

Yun YH et al (2004) Validation of the Korean version of the EORTC QLQ-C30. Qual Life Res 13(4):863–868

Kim SH (2021) Factors affecting quality of life in male bladder cancer survivors with a neobladder. Chung-Ang University, Seoul

Park KH, Song MK (2022) Priority Analysis of Educational Needs of Forest Healing Instructors Related to Programs for Cancer Survivors: Using Borich Needs Assessment and the Locus for Focus Model. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(9)

Cutillo A et al (2015) A literature review of nature-based therapy and its application in cancer care. J Ther Hortic 25(1):3–15

Berger AM et al (2010) NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines Cancer-related fatigue. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 8(8):904–931

Cohen J (2013) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Academic press

Gilliam LA, St Clair DK (2011) Chemotherapy-induced weakness and fatigue in skeletal muscle: the role of oxidative stress. Antioxid Redox Signal 15(9):2543–2563

Suesada MM et al (2018) Impact of thoracic radiotherapy on respiratory function and exercise capacity in patients with breast cancer. J Bras Pneumol 44(6):469–476

Li Q et al (2008) Visiting a forest, but not a city, increases human natural killer activity and expression of anti-cancer proteins. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol 21(1):117–127

Docherty S et al (2022) The effect of exercise on cytokines: implications for musculoskeletal health: a narrative review. BMC Sports Sci Med Rehabil 14(1):5

Pedersen BK et al (2001) Exercise and cytokines with particular focus on muscle-derived IL-6. Exerc Immunol Rev 7:18–31

Nara H, Watanabe R (2021) Anti-Inflammatory Effect of Muscle-Derived Interleukin-6 and Its Involvement in Lipid Metabolism. Int J Mol Sci 22(18)

Jimenez MP et al (2021) Associations between Nature Exposure and Health: A Review of the Evidence. J Environ Res Public Health 18(9)

Satyawan V, Rusdiana O, Latifah M (2022) The role of forest therapy in promoting physical and mental health: A systematic review. In: IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. IOP Publishing

Kim H et al (2020) Effect of Forest Therapy for Menopausal Women with Insomnia. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(18)

McDonough MH et al (2021) Social support and physical activity for cancer survivors: a qualitative review and meta-study. J Cancer Surviv 15(5):713–728

Funding

This research was supported by the ‘R&D’ program for Forest Science Technology (Project No. 2021393A00-2123-0103) provided by Korea Forest Service (Korea Forestry Promotion Institute) and the Gachon University research fund of 2021 (GCU- 202206020001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Kwang-Hi Park, Haneul Lee, Eun Young Park contributed to the purpose of the study and the study design. Haneul Lee, Esther Bang, SangYi Baek, Yerim Do, Sieun Lee, and Youngeun Lim investigated and analyzed data. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Kwaing-Hi Park, Haneul Lee, and JiHyun Sung, and all authors critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Gachon University (approval no. 1044396-202103-HR-055-03) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent for research involving human participants

Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

ESM 1

(DOCX 16 kb)

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Park, KH., Lee, H., Park, E.Y. et al. Effects of an urban forest healing program on cancer-related fatigue in cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 32, 4 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-023-08214-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-023-08214-3