Abstract

Objective

To identify baseline factors associated with disease activity in patients with relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) under teriflunomide treatment.

Methods

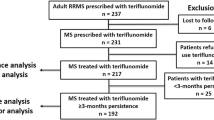

This was an independent, multi-centre, retrospective post-marketing study. We analysed data of 1,507 patients who started teriflunomide since October 2014 and were regularly followed in 28 Centres in Italy. We reported the proportions of patients who discontinued treatment (after excluding 32 lost to follow-up) and who experienced clinical disease activity, i.e., relapse(s) and/or confirmed disability worsening, as assessed by the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS). Decision tree-based analysis was performed to identify baseline factors associated with clinical disease activity during teriflunomide treatment.

Results

At database lock (September 2020), approximately 29% of patients (430 out of 1,475) discontinued teriflunomide because of disease activity (~ 46%), adverse events (~ 37%), poor tolerability (~ 15%), pregnancy planning (~ 2%). Approximately 28% of patients experienced disease activity over a median follow-up of 2.75 years: ~ 9% had relapses but not disability worsening; ~ 13% had isolated disability worsening; ~ 6% had both relapses and disability worsening. The most important baseline factor associated with disease activity (especially disability worsening) was an EDSS > 4.0 (p < 0.001). In patients with moderate disability level (EDSS 2.0–4.0), disease activity occurred more frequently in case of ≥ 1 pre-treatment relapses (p = 0.025). In patients with milder disability level (EDSS < 2.0), disease activity occurred more frequently after previous exposure to ≥ 2 disease-modifying treatments (p = 0.007).

Conclusions

Our study suggests a place-in-therapy for teriflunomide in naïve patients with mild disability level or in those who switched their initial treatment for poor tolerability. Adverse events related with teriflunomide were consistent with literature data, without any new safety concern.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (luca.prosperini@gmail.com) upon reasonable request.

References

Scott LJ (2019) Teriflunomide: a review in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Drugs 79(8):875–886

Cherwinski HM, Cohn RG, Cheung P et al (1995) The immunosuppressant leflunomide inhibits lymphocyte proliferation by inhibiting pyrimidine biosynthesis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 275(2):1043–1049

Rückemann K, Fairbanks LD, Carrey EA et al (1998) Leflunomide inhibits pyrimidine de novo synthesis in mitogen-stimulated T-lymphocytes from healthy humans. J Biol Chem 273(34):21682–21691

Bar-Or A, Pachner A, Menguy-Vacheron F, Kaplan J, Wiendl H (2014) Teriflunomide and its mechanism of action in multiple sclerosis. Drugs 74(6):659–674

O’Connor P, Comi G, Benzerdjeb H, Miller A (2011) Randomized trial of oral teriflunomide for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 365:1293–1303

Confavreux C, O’Connor P, Comi G et al (2014) Oral teriflunomide for patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis (TOWER): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Neurol 13(3):247–256

Miller AE, Wolinsky JS, Kappos L et al (2014) Oral teriflunomide for patients with a first clinical episode suggestive of multiple sclerosis (TOPIC): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Neurol 13:977–986

Vermersch P, Czlonkowska A, Grimaldi LM et al (2014) Teriflunomide versus subcutaneous interferon beta-1a in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis: a randomised, controlled phase 3 trial. Mult Scler 20(6):705–716

Coyle PK, Khatri B, Edwards KR et al (2017) Patient-reported outcomes in relapsing forms of MS: real-world, global treatment experience with teriflunomide from the Teri-PRO study. Mult Scler Relat Disord 17:107–115

Coyle PK, Khatri B, Edwards KR et al (2018) Patient-reported outcomes in patients with relapsing forms of MS switching to teriflunomide from other disease-modifying therapies: results from the global Phase 4 Teri-PRO study in routine clinical practice. Mult Scler Relat Disord 26:211–218

Coyle PK, Khatri B, Edwards KR et al (2019) Teriflunomide real-world evidence: global differences in the phase 4 Teri-PRO study. Mult Scler Relat Disord 31:157–164

Buron MD, Chalmer TA, Sellebjerg F et al (2019) Comparative effectiveness of teriflunomide and dimethyl fumarate: a nationwide cohort study. Neurology 92(16):e1811–e1820

Kalincik T, Kubala Havrdova E, Horakova D et al (2019) Comparison of fingolimod, dimethyl fumarate and teriflunomide for multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 90(4):458–468

Laplaud D-A, Casey R, Barbin L et al (2019) Comparative effectiveness of teriflunomide vs. dimethyl fumarate in multiple sclerosis. Neurology 93(7):e635–e646

D’Amico E, Zanghì A, Sciandra M et al (2020) Dimethyl fumarate vs. Teriflunomide: an Italian time-to-event data analysis. J Neurol 267(10):3008–3020

Miller AE, O’Connor P, Wolinsky JS et al (2012) Pre-specified subgroup analyses of a placebo-controlled phase III trial (TEMSO) of oral teriflunomide in relapsing multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 18(11):1625–1632

Freedman MS, Wolinsky JS, Comi G et al (2018) The efficacy of teriflunomide in patients who received prior disease-modifying treatments: Subgroup analyses of the teriflunomide phase 3 TEMSO and TOWER studies. Mult Scler 24(4):535–539

Elkjaer ML, Molnar T, Illes Z (2017) Teriflunomide for multiple sclerosis in real-world setting. Acta Neurol Scand 136(5):447–453

Vukusic S, Coyle PK, Jurgensen S et al (2020) Pregnancy outcomes in patients with multiple sclerosis treated with teriflunomide: clinical study data and 5 years of post-marketing experience. Mult Scler 26(7):829–836

Polman CH, Reingold SC, Banwell B et al (2011) Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteria. Ann Neurol 69(2):292–302

Thompson AJ, Banwell BL, Barkhof F et al (2018) Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: 2017 revisions of the McDonald criteria. Lancet Neurol 17(2):162–173

Lublin FD, Reingold SC, Cohen JA et al (2014) Defining the clinical course of multiple sclerosis: the 2013 revisions. Neurology 83(3):278–286

Kurtzke JF (1983) Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Neurology 33(11):1444–1452

Río J, Nos C, Tintoré M et al (2006) Defining the response to interferon-beta in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis patients. Ann Neurol 59(2):344–352

Filippi M, Rocca MA, Bastianello S et al (2013) Guidelines from the Italian neurological and neuroradiological societies for the use of magnetic resonance imaging in daily life clinical practice of multiple sclerosis patients. Neurol Sci 34(12):2085–2093

O’Connor PW, Li D, Freedman MS et al (2006) A Phase II study of the safety and efficacy of teriflunomide in multiple sclerosis with relapses. Neurology 66(6):894–900

Lanzillo R, Prosperini L, Gasperini C et al (2018) A multicentRE observational analysiS of PErsistenCe to treatment in the new multiple sclerosis era: the RESPECT study. J Neurol 265(5):1174–1183

Krzywinski M, Altman N (2017) Classification and regression trees. Nat Methods 14(8):757–758

Leray E, Yaouanq J, Le Page E et al (2010) Evidence for a two-stage disability progression in multiple sclerosis. Brain 133(7):1900–1913

Pardo G, Jones DE (2017) The sequence of disease-modifying therapies in relapsing multiple sclerosis: safety and immunologic considerations. J Neurol 264(12):2351–2374

O’Connor P, Comi G, Freedman MS et al (2016) Long-term safety and efficacy of teriflunomide: 9-year follow-up of the randomized TEMSO study. Neurology 86(10):920–930

Miller AE, Olsson TP, Wolinsky JS et al (2020) Long-term safety and efficacy of teriflunomide in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis: results from the TOWER extension study. Mult Scler Relat Disord 46:102438

Gasperini C, Prosperini L, Tintoré M et al (2019) Unraveling treatment response in multiple sclerosis: a clinical and MRI challenge. Neurology 92(4):180–192

Acknowledgements

Collaborator List (TER-Italy Study Group), see Supplementary Material.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. Pietro Annovazzi: consulting and/or lecture fees from Mylan, Roche, Almirall e Merck, Biogen, Genzyme, Novartis and Teva. Valeria Barcella: personal compensation for advisory boards and/or speaker’s honoraria from Almirall, Biogen, Merck, Novartis, Roche and Sanofi-Genzyme. Roberto Bergamaschi: personal compensation for scientific advisory boards from Biogen and Almirall; funding for travel and speaker honoraria from Sanofi-Aventis, Genzyme, Biogen, Bayer Schering, Teva, Merck Serono, Almirall, Roche and Novartis; research support from Merck Serono, Biogen Idec, Teva, Bayer Schering, Novartis, Sanofi-Aventis. Giovanna Borriello: travel grants and lecture fees from Almirall, Biogen, Genzyme, Merck, Novartis, Roche, Teva. Maria Chiara Buscarinu: advisory board membership and honoraria for speaking from Teva, Novartis, Sanofi, Merck Serono, and Biogen. Graziella Callari: personal fees from Biogen and Sanofi; travel funding from Bayer, Biogen, and Merck. Marco Capobianco: personal compensation for advisory boards or speaker’s honoraria from Almirall, Biogen, Merck, Novartis, Roche, Sanofi-Genzyme and Teva. Fioravanti Capone: travel grants from Biogen, Merck and Sanofi-Genzyme. Paola Cavalla: personal compensation for advisory boards from Biogen Idec, Teva, Almirall, Sanofi-Genzyme and Merck-Serono; honoraria as a speaker from Biogen, Merck-Serono, Teva, Roche, Novartis and Sanofi-Genzyme; travel grants from Biogen, Merck-Serono, Teva, Roche, Novartis and Sanofi-Genzyme. Antonio Cortese: honoraria for speaking and travel grants from Biogen, Sanofi-Genzyme, and Teva. Giovanna De Luca: travel grants and/or speaker honoraria from Merck-Serono, Roche, Sanofi Genzyme and Biogen. Massimiliano Di Filippo: personal compensation for advisory boards, speaker or writing honoraria, and funding for travelling from Bayer, Biogen, Genzyme, Merck, Mylan, Novartis, Roche and Teva. Roberta Fantozzi: travel grants and/or speaker honoraria from Biogen, Merck and Roche. Massimo Filippi: Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of Neurology; compensation for consulting services and/or speaking activities from Bayer, Biogen, Merck-Serono, Novartis, Roche, Sanofi Genzyme, Takeda, and Teva Pharmaceutical Industries; research support from Biogen, Merck-Serono, Novartis, Roche, Teva Pharmaceutical Industries, Italian Ministry of Health, Fondazione Italiana Sclerosi Multipla, and ARiSLA (Fondazione Italiana di Ricerca per la SLA). Claudio Gasperini: personal compensation for advisory boards from Biogen, Teva, Bayer, Genzyme and Merck; honoraria as speaker from Biogen, Merck, Almirall, Bayer, Teva, Roche, Novartis and Sanofi-Genzyme. Luigi Maria Edoardo Grimaldi: scientific advisory board for Merck Serono; funding for travel or speaker honoraria from Merck Serono, Biogen, Sanofi-Aventis, Bayer Schering and Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; institutional research support form Teva Pharmaceuticals Industries Ltd, Biogen, Genzyme Corporation, Sanofi-Aventis, Merck Serono, Novartis and Eisai Inc.; research support from Merck Serono, Biogen and Ministero della Salute of Italy. Doriana Landi: travel funding from Biogen, Merck, Sanofi, Teva; speaking or consultations fees from Sanofi, Merck, Teva, Biogen, Roche. Girolama Alessandra Marfia: advisory board membership for Biogen, Genzyme, Merck-Serono, Novartis, and Teva; honoraria for speaking or consultation fees from Almirall, Bayer Schering, Biogen Idec, Genzyme, Merck Serono, Novartis, and Teva. Massimiliano Mirabella: membership of scientific advisory boards for Bayer Schering, Biogen, Sanofi-Genzyme, Merck, Novartis, Teva; consulting and/or speaking fees, research support or travel grants from Almirall, Bayer Schering, Biogen, CSL Behring Sanofi-Genzyme, Merck, Novartis, Teva, Roche, Ultragenix. Paola Perini: speaking honoraria and/or consultant fees from Biogen, Merck Serono, Teva, Novartis and Genzyme. Luca Prosperini: consulting fees from Biogen, Celgene, Novartis and Roche; speaker honoraria from Biogen, Genzyme, Merck Serono, Mylan, Novartis and Teva; travel grants from Biogen, Genzyme, Novartis and Teva; research grants from the Italian MS Society (Associazione Italiana Sclerosi Multipla) and Genzyme. Mauro Zaffaroni: grants for participating in advisory boards or attending scientific meetings from Biogen, Merck, Novartis and Sanofi-Genzyme. Cristina Zuliani: speaker’s honoraria and consulting fees, honoraria for advisory boards, support for attendance of scientific meetings from Almirall, Bayer Shering, Biogen, Merck Serono, Novartis, Roche, Sanofi Genzyme, and Teva. MA, AB, RC, VD, EF, MMF, MLR, GM, PM, MP, PR, MR, VT, VLAT-C, SZ, report no conflict of interest.

Ethical statement

The present study was conducted in accordance with specific national laws and the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. Given its retrospective design, in no way this study did interfere with the care received by patients.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bucello, S., Annovazzi, P., Ragonese, P. et al. Real world experience with teriflunomide in multiple sclerosis: the TER-Italy study. J Neurol 268, 2922–2932 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-021-10455-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-021-10455-3