Abstract

Background

Positive effects of pistachio nut consumption on plasma inflammatory biomarkers have been described; however, little is known about molecular events associated with these effects.

Purpose

We studied the anti-inflammatory activity of a hydrophilic extract from Sicilian Pistacia L. (HPE) in a macrophage model and investigated bioactive components relevant to the observed effects.

Methods

HPE oligomer/polymer proanthocyanidin fractions were isolated by adsorbance chromatography, and components quantified as anthocyanidins after acidic hydrolysis. Isoflavones were measured by gradient elution HPLC analysis. RAW 264.7 murine macrophages were pre-incubated with either HPE (1- to 20-mg fresh nut equivalents) or its isolated components for 1 h, then washed before stimulating with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) for 24 h. Cell viability and parameters associated with Nuclear Factor-κB (NF-κB) activation were assayed according to established methods including ELISA, Western blot, or cytofluorimetric analysis.

Results

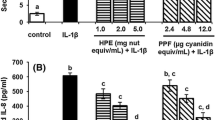

HPE suppressed nitric oxide (NO) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) production and inducible NO-synthase levels dose dependently, whereas inhibited prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) release and decreased cyclo-oxygenase-2 content, the lower the HPE amount the higher the effect. Cytotoxic effects were not observed. HPE also caused a dose-dependent decrease in intracellular reactive oxygen species and interfered with the NF-κB activation. Polymeric proanthocyanidins, but not isoflavones, at a concentration comparable with their content in HPE, inhibited NO, PGE2, and TNF-α formation, as well as activation of IκB-α. Oligomeric proanthocyanidins showed only minor effects.

Conclusions

Our results provide molecular evidence of anti-inflammatory activity of pistachio nut and indicate polymeric proanthocyanidins as the bioactive components. The mechanism may involve the redox-sensitive transcription factor NF-κB. Potential effects associated with pistachio nut consumption are discussed in terms of the proanthocyanidin bioavailability.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Dreher ML, Maher CV, Kearney P (1996) The traditional and emerging role of nuts in healthful diets. Nutr Rev 54:241–245

Blomhoff R, Carlsen MH, Frost Andersen L, Jacobs DR Jr (2006) Health benefits of nuts: potential role of antioxidants. Br J Nutr 96:S52–S60

Ros E, Mataix J (2006) Fatty acid composition of nuts. Implications for cardiovascular health. Br J Nutr 96:S29–S35

Segura R, Javierre C, Lizarraga MA, Ros E (2006) Other relevant components of nuts: phytosterols, folates and minerals. Br J Nutr 96:S36–S44

Fraser GE, Sabate J, Beeson WL, Strahan TM (1992) A possible protective effect of nut consumption on risk of coronary heart disease. The adventist health study. Arch Intern Med 152:1416–1424

Prineas RJ, Kushi LH, Folsom AR, Bostick RM, Wu Y (1993) Walnuts and serum lipids. N Engl J Med 329:359

Hu FB, Stampfer MJ, Manson JE, Rimm EB, Colditz GA, Rosner BA, Speizer FE, Hennekens CH, Willett WC (1998) Frequent nut consumption and risk of coronary heart disease in women: prospective cohort study. BMJ 317:1341–1345

Hu FB, Stampfer MJ (1999) Nut consumption and risk of coronary heart disease: a review of epidemiological evidence. Curr Atheroscler Rep 1:204–209

Kris-Etherton PM, Zhao G, Binkoski AE, Coval SM, Etherton TD (2001) The effects of nuts on coronary heart disease risk. Nutr Rev 59:103–111

Albert CM, Gaziano JM, Willett WC, Manson JE (2002) Nut consumption and decreased risk of sudden cardiac death in the physicians’ health study. Arch Intern Med 162:1382–1387

Mukudden-Pedersen J, Oosthuizen W, Jerling JC (2005) A systematic review of the effects of nuts on blood lipid profiles in humans. J Nutr 135:2082–2089

Giner-Larza EM, Manez S, Recio MC, Giner RM, Prieto JM, Cerda-Nicolas M, Rios JL (2001) Oleanonic acid, a 3-oxotriterpene from pistacia, inhibits leukotriene synthesis and has anti-inflammatory activity. Eur J Pharmacol 428:137–143

Duru ME, Cakir A, Kordali S, Zengin H, Harmandar M, Izumi S, Hirata T (2003) Chemical composition and antifungal properties of essential oils of three pistacia species. Fitoterapia 74:170–176

Ozcelik B, Aslan M, Orhan I, Karaoglu T (2005) Antibacterial, antifungal, and antiviral activities of the lipophylic extracts of Pistacia vera. Microbiol Res 160:159–164

Orhan I, Kupeli E, Aslan M, Kartal M, Yesilada E (2006) Bioassay-guided evaluation of anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive activities of pistachio, Pistacia vera L. J Ethnopharmacol 105:235–240

Edwards K, Kwaw I, Matud J, Kurtz I (1999) Effects of pistachio nuts on serum lipid levels in patients with moderate hypercholesterolemia. J Am Coll Nutr 18:229–232

Kocyigit A, Koylu AA, Keles H (2006) Effects of pistachio nut consumption on plasma lipid profile and antioxidative status in healthy volunteers. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 16:202–209

Sheridan MJ, Cooper JN, Erario M, Cheifetz CE (2007) Pistachio nut consumption and serum lipid levels. J Am Coll Nutr 26:141–148

Gebauer SK, West SG, Kay CD, Alaupovic P, Bagshaw D, Kris Etherton PM (2008) Effects of pistachios on cardiovascular disease risk factors and potential mechanisms of action: a dose-response study. Am J Clin Nutr 88:651–659

Sari I, Baltaci Y, Bagci C, Davutoglu V, Erel O, Celik H, Ozer O, Aksoy N, Aksoy M (2010) Effect of pistachio diet on lipid parameters, endothelial function, inflammation, and oxidative status: a prospective study. Nutrition 26:399–404

Kinlay S, Egido J (2006) Inflammatory biomarkers in stable atherosclerosis. Am J Cardiol 98:2P–8P

Packard RR, Libby P (2008) Inflammation in atherosclerosis: from vascular biology to biomarker discovery and risk prediction. Clin Chem 54:24–38

Wilson PW (2008) Evidence of systemic inflammation and estimation of coronary artery disease risk: a population perspective. Am J Med 121:S15–S20

Gentile C, Tesoriere L, Butera D, Fazzari M, Monastero M, Allegra M, Livrea MA (2007) Antioxidant activity of sicilian pistachio (Pistacia vera L. var. Bronte) nut extract and its bioactive components. J Agric Food Chem 55:643–648

Jordão AM, Gonçalves FJ, Correia AC, Cantão J, Rivero-Pérez MD, González Sanjosé ML (2010) Proanthocyanidin content, antioxidant capacity and scavenger activity of Portuguese sparkling wines (Bairrada Appellation of Origin). J Sci Food Agric 90:2144–2152

Porter JP, Hrstich LN, Chan BG (1985) The conversion of procyanidin and prodelphinidins to cyaniding and delphinidin. Phytochemistry 25:223–230

Barnes PJ, Karin M (1997) Nuclear factor-kB: a pivotal transcription factor in chronic inflammatory diseases. N Engl J Med 336:1066–1071

Aktan F (2004) iNOS-mediated nitric oxide production and its regulation. Life Sci 75:639–653

Herschman HR (1996) Prostaglandin synthase 2. Biochim Biophys Acta 1299:125–140

Tilley SL, Coffman TM, Koller BH (2001) Mixed messages: modulation of inflammation and immune responses by prostaglandins and thromboxanes. J Clin Invest 108:15–23

Tsasanis C, Androulidaki A, Venihaki M, Margioris AN (2006) Signalling networks regulating cyclooxygenase-2. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 38:1654–1661

Aggarwal BB (2004) Nuclear factor-kB: the enemy within. Cancer Cell 6:203–208

Baeuerle PA, Henkel T (1994) Function and activation of NF-kB in the immune system. Annu Rev Immunol 12:141–179

Gloire G, Legrand-Poels S, Piette J (2006) NF-kB activation by reactive oxygen species: fifteen years later. Biochem Pharmacol 72:1493–1505

Gill R, Tsung A, Billiar T (2010) Linking oxidative stress to inflammation: toll-like receptors. Free Radic Biol Med 48:1121–1132

Park HS, Jung HY, Park EY, Kim J, Lee WJ, Bae YS (2004) Cutting edge: direct interactions of TLR4 with NADPH oxidase 4 isozyme is essential for lipopolysaccharide-induced production of reactive oxygen species and activation of NF-kB. J Immunol 173:3589–3593

Lambeth JD (2004) NOX enzymes and the biology of reactive oxygen. Nutr Rev Immunol 1:181–189

Gloire G, Piette J (2009) Redox regulation of nuclear post-translational modifications during NF-kB activation. Antiox Redox Signal 11:2209–2222

Blay M, Espinel AE, Delgado MA, Baiges I, Bladé C, Arola L, Salvadó J (2010) Isoflavone effect on gene expression profile and biomarkers of inflammation. J Pharm Biomed Anal 51:382–390

Dijsselbloem N, Goriely S, Albarani V, Gerlo S, Francoz S, Marine J-C, Goldman M, Haegeman G, Vanden BW (2007) A critical role for p53 in the control of NF-κB-dependent gene expression in TLR4-stimulated dendritic cells exposed to genistein. J Immunol 178:5048–5057

Li WG, Zhang XY, Wu YJ, Tian X (2001) Anti-inflammatory effect and mechanism of proanthocyanidins from grape seeds. Acta Pharm Sin 22:1117–1120

Das DK, Kalfin R, Righi A, Del Rosso A, Bagchi D, Generini S, Guiducci S, Cerinic MM (2002) Activin, a grapeseed-derived proanthocyanidin extract, reduces plasma levels of oxidative stress and adhesion molecules (ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and E-selectin) in systemic sclerosis. Free Radical Res 36:819–825

Hou DX, Masuzaki S, Hashimoto F, Uto T, Tanigawa S, Fujii M, Sakata Y (2007) Green tea proanthocyanidins inhibit cyclooxygenase-2 expression in LPS-activated mouse macrophages: molecular mechanisms and structure-activity relationship. Arch Biochim Biophys 460:67–74

Terra X, Valls J, Vitrac X, Mérrillon JM, Arola L, Ardèvol A, Bladé C, Fernandez-Larrea J, Pujadas G, Salvadó J, Blay M (2007) Grape-seed procyanidins act as antiinflammatory agents in endotoxin-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages by inhibiting NFkB signaling pathway. J Agric Food Chem 55:4357–4365

Virgili F, Kobuchi H, Packer L (1998) Procyanidins extracted from Pinus maritime (Pycnogenol): scavengers of free radical species and modulators of nitrogen monoxide metabolism in activated murine RAW 264.7 macrophages. Free Radic Biol Med 24:1120–1129

Zhang W-y, Liu H-q, Xie K-q, Yin L-l, Li Y, Kwik-Uribe CL, Zhu X-z (2006) Procyanidin dimer B2 [epicathechin-(4β8)-epicathechin] suppresses the expression of cyclooxygenase-2 in endotoxin-treated monocytic cells. Biochim Biophys Res Commun 345:508–515

Jung M, Triebel S, Anke T, Richling E, Erkel G (2009) Influence of apple polyphenols on inflammatory gene expression. Molec Nutr Food Res 53:1263–1280

Ho S-C, Hwang LS, Shen Y-J, Lin C–C (2007) Suppressive effect of a proanthocyanidin-rich extract from longan (Dimocarpus longan Lour.) flowers on nitric oxide production in LPS-stimulated macrophage cells. J Agric Food Chem 55:10664–10670

Park YC, Rimbach G, Saliou C, Valacchi G, Packer L (2000) Activity of monomeric, dimeric, and trimeric flavonoids on NO production, TNF-α secretion, and NFkB-dependent gene expression in macrophages. FEBS Lett 465:93–97

Williams RJ, Spencer JP, Rice-Evans C (2004) Flavonoids: antioxidants or signalling molecules? Free Radic Biol Med 36:838–849

Plumb GW, De-Pascual-Teresa S, Santos-Buelga C, Chenier V, Williamson G (1998) Antioxidant properties of cathechins and proanthocyanidins: effect of polymerization, galloylation and glycosylation. Free Radic Res 29:351–358

Hendrich AB (2006) Flavonoid-membrane interactions: possible consequences for biological effects of some polyphenolic compounds. Acta Pharmacol Sinica 27:27–40

Delehanty JB, Johnson BJ, Hickey TE, Pons T, Ligler FS (2007) Binding and neutralization of lipopolysaccharides by plant proanthocyanidins. J Nat Prod 70:1718–1724

Cuschieri J, Maier RV (2007) Oxidative stress, lipid raft, and macrophage reprogramming. Antiox Redox Signal 9:1485–1498

Lu YC, Yeh WC, Ohashi PS (2008) LPS/TLR4 signal transduction pathway. Cytokine 42:145–151

Lee JK, Kim SY, Kim YS, Lee W-H, Hwang D, Lee JY (2009) Suppression of the TRIF-dependent signaling pathway of Toll-like receptors by luteolin. Biochem Pharmacol 77:1391–1400

Wang L, Zhu LH, Jiang H, Tang Q-Z, Yan L, Wang D, Liu C, Bian Z-y, Li H (2010) Grape seed proanthocyanidins attenuate vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation via blocking phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-dependent signaling pathways. J Cell Physiol 223:713–726

Manach C, Williamson G, Morand C, Scalbert A, Rémésy C (2005) Bioavailability and bioefficacy of polyphenols in humans. I. review of 97 bioavailability studies. Am J Clin Nutr 81:230S–242S

Appeldoorn MM, Vincken JP, Gruppen H, Hollman PC (2009) Procyanidin dimers A1, A2, and B2 are absorbed without conjugation or methylation from the small intestine of rats. J Nutr 139:1469–1473

Holt RR, Lazarus SA, Sullards MC, Zhu QY, Schramm DD, Hammerstone JF, Fraga CG, Schmitz HH, Keen CL (2002) Procyanidin dimer B2[epicathechin (4β-8)-epicathechin] in human plasma after the consumption of a flavonol-rich cocoa. Am J Clin Nutr 76:798–804

Rios LY, Bennett RN, Lazarus SA, Rémésy C, Scalbert A, Williamson G (2002) Cocoa procyanidins are stable during gastric transit in humans. Am J Clin Nutr 76:1106–1110

Halliwell B, Rafter J, Jenner A (2005) Health promotion by flavonoids, tocopherols, tocotrienols, and other phenols: direct or indirect effects? Antioxidant or not? Am J Clin Nutr 81:268S–276S

USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference (www.ars.usda.gov/ba/bhnrc/ndl)

Mahe S, Huneau JF, Marteau P, Thuillier F, Tome D (1992) Gastroileal nitrogen and humans. Am J Clin Nutr 56:410–416

Acknowledgments

This work has been carried out by a grant from Assessorato Agricoltura e Foreste Regione Sicilia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gentile, C., Allegra, M., Angileri, F. et al. Polymeric proanthocyanidins from Sicilian pistachio (Pistacia vera L.) nut extract inhibit lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory response in RAW 264.7 cells. Eur J Nutr 51, 353–363 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-011-0220-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-011-0220-5