Abstract

Purpose

Alterations in the urinary microbiome have been associated with urological diseases. The microbiome of patients with urethral stricture disease (USD) remains unknown. Our objective is to examine the microbiome of USD with a focus on inflammatory USD caused by lichen sclerosus (LS).

Methods

We collected mid-stream urine samples from men with LS-USD (cases; n = 22) and non-LS USD (controls; n = 76). DNA extraction, PCR amplification of the V4 hypervariable region of the 16S rRNA gene, and sequencing was done on the samples. Operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were defined using a > 97% sequence similarity threshold. Alpha diversity measurements of diversity, including microbiome richness (number of different OTUs) and evenness (distribution of OTUs) were calculated and compared. Microbiome beta diversity (difference between microbial communities) relationships with cases and controls were also assessed.

Results

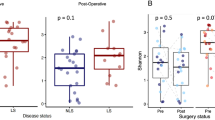

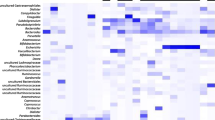

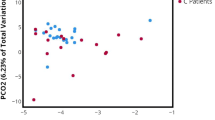

Fifty specimens (13 cases and 37 controls) produced a 16S rRNA amplicon. Mean sample richness was 25.9 vs. 16.8 (p = 0.076) for LS-USD vs. non-LS USD, respectively. LS-USD had a unique profile of bacteria by taxonomic order including Bacillales, Bacteroidales and Pasteurellales enriched urine. The beta variation of observed bacterial communities was best explained by the richness.

Conclusions

Men with LS-USD may have a unique microbiologic richness, specifically inclusive of Bacillales, Bacteroidales and Pasteurellales enriched urine compared to those with non-LS USD. Further work will be required to elucidate the clinical relevance of these variations in the urinary microbiome.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Drake MJ, Morris N, Apostolidis A et al (2017) The urinary microbiome and its contribution to lower urinary tract symptoms; ICI-RS 2015. Neurourol Urodyn 36:850–853. https://doi.org/10.1002/nau.23006

Bajic P, Van Kuiken ME, Burge BK et al (2018) Male Bladder Microbiome Relates to Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms. European Urology Focus. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euf.2018.08.001

Mueller ER, Wolfe AJ, Brubaker L (2017) Female urinary microbiota. Curr Opin Urol 27(3):282–286

Schneeweiss J, Koch M, Umek W (2016) The human urinary microbiome and how it relates to urogynecology. Int Urogynecol J 27:1307–1312. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-016-2944-5

Frølund M, Wikström A, Lidbrink P et al (2018) The bacterial microbiota in first-void urine from men with and without idiopathic urethritis. PLoS ONE 13:e0201380. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0201380

Dong Q, Nelson DE, Toh E et al (2011) The microbial communities in male first catch urine are highly similar to those in paired urethral swab specimens. PLoS ONE 6:e19709. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0019709

Belkaid Y, Hand TW (2014) Role of the microbiota in immunity and inflammation. Cell 157:121–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.011

Buford TW (2017) (Dis)Trust your gut: the gut microbiome in age-related inflammation, health, and disease. Microbiome 5:80. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-017-0296-0

Fischbach MA, Segre JA (2016) Signaling in host-associated microbial communities. Cell 164:1288–1300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2016.02.037

Grimes MD, Tesdahl BA, Schubbe M et al (2019) Histopathology of anterior urethral strictures: towards a better understanding of stricture pathophysiology. J Urol. https://doi.org/10.1097/JU.0000000000000340

Pugliese JM, Morey AF, Peterson AC (2007) Lichen sclerosus: review of the literature and current recommendations for management. J Urol 178:2268–2276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2007.08.024

Osterberg EC, Murphy G, Harris CR et al (2017) Cost-effective strategies for the management and treatment of urethral stricture disease. Urol Clin N Am 44:11–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ucl.2016.08.002

Levy A, Browne B, Fredrick A et al (2019) Insights into the pathophysiology of urethral stricture disease due to lichen sclerosus: comparison of pathological markers in lichen sclerosus induced strictures vs nonlichen sclerosus induced strictures. J Urol 201:1158–1163. https://doi.org/10.1097/JU.0000000000000155

Fujimura KE, Sitarik AR, Havstad S et al (2016) Neonatal gut microbiota associates with childhood multisensitized atopy and T cell differentiation. Nat Med 22:1187–1191. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.4176

Whittaker RH (1972) Evolution and measurement of species diversity. Taxon 21:213. https://doi.org/10.2307/1218190

Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J et al (2010) QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods 7:335–336. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.f.303

Love MI, Huber W, Anders S (2014) Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8

Pearce MM, Hilt EE, Rosenfeld AB et al (2014) The female urinary microbiome: a comparison of women with and without urgency urinary incontinence. Blaser MJ, ed. MBio. https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.01283-14

Wu P, Zhang G, Zhao J et al (2018) Profiling the urinary microbiota in male patients with bladder cancer in China. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 8:167. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2018.00167

Shrestha E, White JR, Yu S-H et al (2018) Profiling the urinary microbiome in men with positive versus negative biopsies for prostate cancer. J Urol 199:161–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2017.08.001

Gérard P (2016) Gut microbiota and obesity. Cell Mol Life Sci 73:147–162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-015-2061-5

Carlson BC, Hofer MD, Ballek N et al (2013) Protein markers of malignant potential in penile and vulvar lichen sclerosus. J Urol 190:399–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2013.01.102

Sfanos KS, Yegnasubramanian S, Nelson WG et al (2018) The inflammatory microenvironment and microbiome in prostate cancer development. Nat Rev Urol 15:11–24. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrurol.2017.167

Rajpoot M, Sharma AK, Sharma A et al (2018) Understanding the microbiome: emerging biomarkers for exploiting the microbiota for personalized medicine against cancer. Semin Cancer Biol 52:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcancer.2018.02.003

Bunker CB, Shim TN (2015) Male genital lichen sclerosus. Indian J Dermatol 60(2):111–117

Shogan BD, Smith DP, Christley S et al (2014) Intestinal anastomotic injury alters spatially defined microbiome composition and function. Microbiome 2:35. https://doi.org/10.1186/2049-2618-2-35

Kassiri B, Shrestha E, Kasprenski M et al (2019) A prospective study of the urinary and gastrointestinal microbiome in prepubertal males. Urology. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2019.05.031

Sathiananthamoorthy S, Malone-Lee J, Gill K et al (2018) Reassessment of routine midstream culture in diagnosis of urinary tract infection. Munson E, ed. J Clin Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.01452-18

Pollock J, Glendinning L, Wisedchanwet T et al (2018) The madness of microbiome: attempting to find consensus “best practice” for 16S microbiome studies. Liu S-J, ed. Appl Environ Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.02627-17

Brooks JP, Edwards DJ, Harwich MD et al (2015) The truth about metagenomics: quantifying and counteracting bias in 16S rRNA studies. BMC Microbiol 15:66. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-015-0351-6

Dill-McFarland KA, Tang Z-Z, Kemis JH et al (2019) Close social relationships correlate with human gut microbiota composition. Sci Rep 9:703. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-37298-9

Lax S, Sangwan N, Smith D et al (2017) Bacterial colonization and succession in a newly opened hospital. Sci Transl Med. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.aah6500

Funding

This work was made possible by generous gifts from Jonathan Kaplan, the Alafi fund, and Anita and Kevan Del Grande Funding was provided by Alafi Foundation (Grant no. 10001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cohen, A.J., Gaither, T.W., Srirangapatanam, S. et al. Synchronous genitourinary lichen sclerosus signals a distinct urinary microbiome profile in men with urethral stricture disease. World J Urol 39, 605–611 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-020-03198-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-020-03198-9