Abstract

Purpose

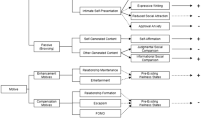

Lifestyle risk factors, such as alcohol use, smoking, high body mass index, poor sleep, and sedentary behavior, represent major public health issues for adolescents. These factors have been associated with increased rates of major depressive disorder (MDD). The purpose of this paper is to investigate critical peaks in the prevalence of MDD at certain ages and to examine how these peaks might be amplified or attenuated by the presence of lifestyle risk factors.

Methods

A nationally representative sample of adolescents aged 11–17 years old (n = 2967) and time-varying effect models were used to investigate the associations between lifestyle risk factors and the prevalence of MDD by sex.

Results

The estimated prevalence of MDD significantly increased among adolescents from 4% (95% CI 3–6%) at 13 years of age to 19% (95% CI 15–24%) at 16 years of age. From the age of 13, males were significantly less likely to have a diagnosis of MDD than females with the maximum sex difference occurring at the age of 15 (OR 0.24, 95% CI 0.13–0.47). All lifestyle risk factors were at some point significantly associated with MDD, but these associations did not differ by sex, except for body mass index.

Discussion

These findings suggest that interventions designed to prevent the development of depression should be implemented in early adolescence, ideally before or at the age of 13 and particularly among young females given that the prevalence of MDD begins to rise and diverge from young males. Interventions should also simultaneously address lifestyle risk factors and symptoms of major depression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Body mass index was used in the current study as a proxy measure for low physical activity and poor diet given the well-established correlation between poor physical activity, poor diet, and high BMI.

Preliminary analysis examined the fit on linear versus non-linear models for the age-varying relationship between all covariates and MDD. On all occasions, the non-linear models provided superior fit based on AIC and BIC values and therefore justified the use of TVEMs in this study. The results are provided in Supplementary Table 1.

References

Ciobanu LG, Ferrari AJ, Erskine HE et al (2018) The prevalence and burden of mental and substance use disorders in Australia: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 52:483–490. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867417751641

Sawyer MG, Reece CE, Sawyer ACP et al (2018) Has the prevalence of child and adolescent mental disorders in Australia changed between 1998 and 2013 to 2014? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 57:343–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JAAC.2018.02.012

Lawrence D, Hafekost J, Johnson SE et al (2016) Key findings from the second Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 50:876–886. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867415617836

Odgers CL, Caspi A, Nagin DS et al (2008) Is it important to prevent early exposure to drugs and alcohol among adolescents? Psychol Sci 19:1037–1044. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02196.x

Teixeira PJ, Carraça EV, Markland D et al (2012) Exercise, physical activity, and self-determination theory: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 9:78. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-9-78

Smit CR, de Leeuw RNH, Bevelander KE et al (2018) An integrated model of fruit, vegetable, and water intake in young adolescents. Health Psychol 37:1159–1167. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000691

Knell G, Durand CP, Kohl HW et al (2019) Prevalence and likelihood of meeting sleep, physical activity, and screen-time guidelines among US youth. JAMA Pediatr 173:387. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4847

Saunders TJ, Vallance JK (2017) Screen time and health indicators among children and youth: current evidence, limitations and future directions. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 15:323–331. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-016-0289-3

Lien N, Lytle LA, Klepp K-I (2001) Stability in consumption of fruit, vegetables, and sugary foods in a cohort from age 14 to age 21. Prev Med (Baltim) 33:217–226. https://doi.org/10.1006/PMED.2001.0874

Telama R, Yang X, Viikari J et al (2005) Physical activity from childhood to adulthood: a 21-year tracking study. Am J Prev Med 28:267–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AMEPRE.2004.12.003

Wilmot EG, Edwardson CL, Achana FA et al (2012) Sedentary time in adults and the association with diabetes, cardiovascular disease and death: systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetologia 55:2895–2905. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-012-2677-z

Corrao G, Bagnardi V, Zambon A, La Vecchia C (2004) A meta-analysis of alcohol consumption and the risk of 15 diseases. Prev Med (Baltim) 38:613–619. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.11.027

Nocon M, Hiemann T, Müller-Riemenschneider F et al (2008) Association of physical activity with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 15:239–246. https://doi.org/10.1097/HJR.0b013e3282f55e09

von Ruesten A, Weikert C, Fietze I, Boeing H (2012) Association of sleep duration with chronic diseases in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC)-Potsdam study. PLoS ONE 7:e30972. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0030972

Hayward J, Jacka FN, Skouteris H et al (2016) Lifestyle factors and adolescent depressive symptomatology: associations and effect sizes of diet, physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 50:1064–1073. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867416671596

Hayward J, Jacka FN, Waters E, Allender S (2014) Lessons from obesity prevention for the prevention of mental disorders: the primordial prevention approach. BMC Psychiatry 14:254. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-014-0254-3

Kelly AB, Chan GCK, Mason WA, Williams JW (2015) The relationship between psychological distress and adolescent polydrug use. Psychol Addict Behav 29:787–793. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000068

Hussong AM, Ennett ST, Cox MJ, Haroon M (2017) A systematic review of the unique prospective association of negative affect symptoms and adolescent substance use controlling for externalizing symptoms. Psychol Addict Behav 31:137–147. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000247

Short MA, Gradisar M, Lack LC, Wright HR (2013) The impact of sleep on adolescent depressed mood, alertness and academic performance. J Adolesc 36:1025–1033. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ADOLESCENCE.2013.08.007

Jacka FN, Berk M (2013) Depression, diet and exercise. Med J Aust 199:S21–S23. https://doi.org/10.5694/MJA12.10508

Bélair M-A, Kohen DE, Kingsbury M, Colman I (2018) Relationship between leisure time physical activity, sedentary behaviour and symptoms of depression and anxiety: evidence from a population-based sample of Canadian adolescents. BMJ Open 8:e021119. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-021119

Hoare E, Milton K, Foster C, Allender S (2016) The associations between sedentary behaviour and mental health among adolescents: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 13:108. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-016-0432-4

Hussain Z, Griffiths MD (2018) Problematic social networking site use and comorbid psychiatric disorders: a systematic review of recent large-scale studies. Front Psychiatry 9:686. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00686

Shensa A, Escobar-Viera CG, Sidani JE et al (2017) Problematic social media use and depressive symptoms among US young adults: a nationally-representative study. Soc Sci Med 182:150–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SOCSCIMED.2017.03.061

Liu M, Wu L, Yao S (2016) Dose-response association of screen time-based sedentary behaviour in children and adolescents and depression: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Br J Sports Med 50:1252–1258. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2015-095084

Boden JM, Fergusson DM (2011) Alcohol and depression. Addiction 106:906–914. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03351.x

Kingsbury M, Dupuis G, Jacka F et al (2016) Associations between fruit and vegetable consumption and depressive symptoms: evidence from a national Canadian longitudinal survey. J Epidemiol Community Health 70:155–161. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2015-205858

Nemiary D, Shim R, Mattox G, Holden K (2012) The relationship between obesity and depression among adolescents. Psychiatr Ann 42:305–308. https://doi.org/10.3928/00485713-20120806-09

de Wit L, Luppino F, van Straten A et al (2010) Depression and obesity: a meta-analysis of community-based studies. Psychiatry Res 178:230–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PSYCHRES.2009.04.015

Luppino FS, de Wit LM, Bouvy PF et al (2010) Overweight, obesity, and depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 67:220. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.2

Kritsotakis G, Psarrou M, Vassilaki M et al (2016) Gender differences in the prevalence and clustering of multiple health risk behaviours in young adults. J Adv Nurs 72:2098–2113. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12981

Lanza ST, Vasilenko SA, Russell MA (2016) Time-varying effect modeling to address new questions in behavioral research: examples in marijuana use. Psychol Addict Behav 30:939–954. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000208

Linden-Carmichael AN, Vasilenko SA, Lanza ST, Maggs JL (2017) High-intensity drinking versus heavy episodic drinking: prevalence rates and relative odds of alcohol use disorder across adulthood. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 41:1754–1759. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.13475

Fish JN, Rice CE, Lanza ST, Russell ST (2018) Is young adulthood a critical period for suicidal behavior among sexual minorities? Results from a US national sample. Prev Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-018-0878-5

Hafekost J, Johnson S, Lawrence D et al (2016) Introducing ‘young minds matter’. Aust Econ Rev 49:503–514. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8462.12163

Hafekost J, Lawrence D, Boterhoven de Haan K et al (2016) Methodology of young minds matter: the second Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 50:866–875. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867415622270

Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas C, et al (2004) The diagnostic interview schedule for children (DISC). In: Comprehensive handbook of psychological assessment. pp 256–270

Costello EJ, Egger H, Angold A (2005) 10-Year research update review: the epidemiology of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders: I. Methods and Public Health Burden. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 44:972–986. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.CHI.0000172552.41596.6F

National Health and Medical Research Council (2009) Australian guidelines to reduce health risks from drinking alcohol. National Health and Medical Research Council, Canberra

Cole TJ, Flegal KM, Nicholls D, Jackson AA (2007) Body mass index cut offs to define thinness in children and adolescents: international survey. BMJ 335:194. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39238.399444.55

Mihrshahi S, Gow ML, Baur LA (2018) Contemporary approaches to the prevention and management of paediatric obesity: an Australian focus. Med J Aust 209:267–274. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja18.00140

Al-Khudairy L, Loveman E, Colquitt JL et al (2017) Diet, physical activity and behavioural interventions for the treatment of overweight or obese adolescents aged 12–17 years. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012691

Hoare E, Skouteris H, Fuller-Tyszkiewicz M et al (2014) Associations between obesogenic risk factors and depression among adolescents: a systematic review. Obes Rev 15:40–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12069

Robinson M, Kendall GE, Jacoby P et al (2011) Lifestyle and demographic correlates of poor mental health in early adolescence. J Paediatr Child Health 47:54–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1754.2010.01891.x

Raniti MB, Allen NB, Schwartz O et al (2017) Sleep duration and sleep quality: associations with depressive symptoms across adolescence. Behav Sleep Med 15:198–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/15402002.2015.1120198

Mendle J (2014) Why puberty matters for psychopathology. Child Dev Perspect 8:218–222. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12092

Girgus JS, Yang K (2015) Gender and depression. Curr Opin Psychol 4:53–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.COPSYC.2015.01.019

Marceau K, Ram N, Houts RM et al (2011) Individual differences in boys’ and girls’ timing and tempo of puberty: modeling development with nonlinear growth models. Dev Psychol 47:1389–1409. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023838

Le-Ha C, Beilin LJ, Burrows S et al (2018) Age at menarche and childhood body mass index as predictors of cardio-metabolic risk in young adulthood: a prospective cohort study. PLoS ONE 13:e0209355. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0209355

Rosenfield RL, Lipton RB, Drum ML (2009) Thelarche, pubarche, and menarche attainment in children with normal and elevated body mass index. Pediatrics 123:84–88. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2008-0146

Wang H, Lin SL, Leung GM, Schooling CM (2016) Age at onset of puberty and adolescent depression: “Children of 1997” Birth Cohort. Pediatrics 137:e20153231–e20153231. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-3231

Alloy LB, Hamilton JL, Hamlat EJ, Abramson LY (2016) Pubertal development, emotion regulatory styles, and the emergence of sex differences in internalizing disorders and symptoms in adolescence. Clin Psychol Sci 4:867–881. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702616643008

Sequeira M-E, Lewis SJ, Bonilla C et al (2017) Association of timing of menarche with depressive symptoms and depression in adolescence: Mendelian randomisation study. Br J Psychiatry 210:39–46. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.115.168617

Teesson M, Newton NC, Slade T et al (2014) The CLIMATE schools combined study: a cluster randomised controlled trial of a universal Internet-based prevention program for youth substance misuse, depression and anxiety. BMC Psychiatry 14:32. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-14-32

Acknowledgements

†Health4Life Team: The Health4Life team comprises Katherine Mills (The Matilda Centre for Research in Mental Health and Substance Use, The University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia), Leanne Hides (Centre for Youth Substance Abuse Research, School of Psychology, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia), Lexine Stapinski (The Matilda Centre for Research in Mental Health and Substance Use, The University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia), Emma L. Barrett (The Matilda Centre for Research in Mental Health and Substance Use, The University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia), Louise Mewton (Centre for Healthy Brain Ageing, The University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia), Lauren A. Gardner (The Matilda Centre for Research in Mental Health and Substance Use, The University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia).

Funding

Members of the current study were funded in part by the Paul Ramsay Foundation. The second Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing (Young Minds Matter) was funded by the Australian Government Department of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors wish to report no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

The survey data used in the current study received ethical approval from the Department of Health Departmental Ethics Committee (Project 17/2012) in accordance with the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research and the Federal Privacy Act 1988. Ethics approval to access the data was received from UNSW HREC no. 13073.

Informed consent

Participation in the survey was voluntary and written consent was required from all participants.

Additional information

The members of the Health4Life Team listed in acknowledgement section.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sunderland, M., Champion, K., Slade, T. et al. Age-varying associations between lifestyle risk factors and major depressive disorder: a nationally representative cross-sectional study of adolescents. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 56, 129–139 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-020-01888-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-020-01888-8