Abstract

Background

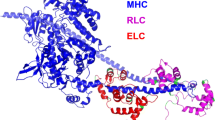

Familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is an autosomal dominant disease characterized by ventricular hypertrophy, myocellular disarray, arrhythmias, and sudden death. Mutations in several contractile proteins, including cardiac myosin heavy chains, have been described in families with this disease, leading to the hypothesis that HCM is a disease of the sarcomere.

Materials and Methods

A mutation in the myosin heavy chain (Myh) predicted to interfere strongly with myosin’s binding to actin was designed and used to create an animal model for HCM. Five independent lines of transgenic mice were produced with cardiac-specific expression of the mutant Myh.

Results

Although the mutant Myh represents a small proportion (1–12%) of the heart’s myosin, the mice exhibit the cardiac histopathology seen in HCM patients. Histopathology is absent from the atria and primarily restricted to the left ventricle. The line exhibiting the highest level of mutant Myh expression demonstrates ventricular hypertrophy by 12 weeks of age, but the further course of the disease is strongly affected by the sex of the animal. Hypertrophy increases with age in female animals while the hearts of male show severe dilation by 8 months of age, in the absence of increased mass.

Conclusions

The low levels of the transgene protein in the presence of the phenotypic features of HCM suggest that the mutant protein acts as a dominant negative. In addition, the distinct phenotypes developed by aging male or female transgenic mice suggest that extragenic factors strongly influence the development of the disease phenotype.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Maron BJ, Bonow RO, Cannon RO, Leon MB, Epstein SE. (1987) Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Interrelations of clinical manifestations, pathophysiology, and therapy. Part one. N. Engl. J. Med. 316: 780–789.

Geisterfer-Lowrance AAT, Kass S, Tanigawa G, et al. (1990) A molecular basis for familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. A β cardiac myosin heavy chain gene missense mutation. Cell 62: 999–1006.

Tanigawa G, Jarcho JA, Kass S, et al. (1990) Molecular basis for familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: A α/β cardiac myosin hybrid gene. Cell 62: 991–998.

Vikstrom KL, Leinwand LA. (1996) Contractile protein mutations and heart disease. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol 8: 97–105.

Thierfelder L, Watkins H, MacRae C, et al. (1994) α-Tropomyosin and cardiac troponin t mutations cause familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: A disease of the sarcomere. Cell 77: 701–712.

Watkins H, McKenna WJ, Thierfelder L, et al. (1995) Mutations in the genes for cardiac troponin t and α-tropomyosin in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 332: 1058–1064.

Bonne G, Carrier L, Bercovici J, et al. (1995) Cardiac myosin binding protein-C gene splice acceptor site mutation is associated with familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Nature Genet. 11: 438–440.

Watkins H, Conner D, Thierfelder L, et al. (1995) Mutations in the cardiac myosin binding protein-C gene on chromosome 11 cause familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Nature Genet. 11: 434–437.

Cuda G, Fananapazir L, Zhu W, Sellers JR, Epstein ND. (1993) Skeletal muscle expression and abnormal function of β-myosin in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J. Clin. Invest. 91: 2861–2865.

Sweeney HL, Straceski AJ, Leinwand LA, Faust L. (1994) Heterologous expression of a cardiomyopathic myosin that is defective in its actin interaction. J. Biol. Chem. 269: 1603–1605.

Ko Y, Tang T, Chen J, Hshieh Y, Wu C, Lien W. (1992) Idiopathic hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in identical twins. Morphological heterogeneity of the left ventricle. Chest 102: 783–785.

Fananapazir L, Epstein ND. (1994) Genotype-phenotype correlations in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Insights provided by comparisons of kindreds with distinct and identical β-myosin heavy chain gene mutations. Circulation 89: 22–32.

Liu S, Roberts WC, Maron BJ. (1993) Comparison of morphologic findings in spontaneously occurring hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in humans, cats and dogs. Am. J. Cardiol. 72: 944–951.

Liu S, Chiu YT, Shyu JJ, et al. (1994) Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in pigs: Quantitative pathologic features in 55 cases. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 3: 261–268.

Geisterfer-Lowrance AAT, Christe M, Conner DA, et al. (1996) A mouse model of familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Science 272: 731–734.

McNally EM, Gianola KM, Leinwand LA. (1989) Complete nucleotide sequence of full length cDNA for rat α myosin heavy chain. Nuclic Acids Res. 17: 7527–7528.

Hogan B, Constantini F, Lacy E. (1986) Manipulating the Mouse Embryo. A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. (1987) Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal. Biochem. 162: 156–169.

Solaro RJ, Pang DC, Briggs N. (1971) The purification of cardiac myofibrils with triton X-100. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 245: 259–262.

Laemmli UK. (1970) Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227: 680–685.

Vikstrom KL, Rovner AS, Bravo-Zehnder M, Saez CG, Straceski AJ, Leinwand LA. (1993) Sarcomeric myosin heavy chain expressed in nonmuscle cells forms thick filaments in the presence of substoichiometric amounts of light chains. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton 26: 192–204.

Rudnicki MA, Jackowski G, Saggin L, McBurney MW. (1990) Actin and myosin expression during development of cardiac muscle from cultured embryonal carcinoma cells. Dev. Biol. 138: 348–358.

Lyons GE, Schiaffino S, Sassoon D, Barton P, Buckingham M. (1990) Developmental regulation of myosin gene expression in mouse cardiac muscle. J. Cell Biol. 111: 2427–3436.

Ng WA, Grupp IL, Subramaniam A, Robbins J. (1991) Cardiac myosin heavy chain mRNA expression and myocardial function in the mouse heart. Circ. Res. 68: 1742–1750.

Quinn-Laquer BK, Kennedy JE, Wei SJ, Beisel KW. (1992) Characterization of the allelic differences in the mouse cardiac a-myosin heavy chain coding sequence. Genomics 13: 176–188.

Rayment I, Holden HM, Whittaker M, et al. (1993) Structure of the actin-myosin complex and its implications for muscle contraction. Science 261: 58–65.

Gustafson TA, Bahl JJ, Markham BE, Roeske WR, Morkin E. (1987) Hormonal regulation of myosin heavy chain and alpha actin gene expression in cultured fetal rat heart myocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 262: 13316–13322.

Subramaniam A, Jones WK, Gulick J, Wert S, Neumann J, Robbins J. (1991) Tissue-specific regulation of the α-myosin heavy chain gene promoter in transgenic mice. J. Biol. Chem. 266: 24613–24620.

Becker AE, Caruso G. (1982) Myocardial disarray. A critical review. Br. Heart J. 47: 527–538.

Wenger NK, Abelmann MH, Roberts WC. (1990) Cardiomyopathy and specific heart muscle disease. In: Hurst JW, Schlant RC, Rackley CE, Sonnenblick EH, Wenger NK (eds). The Heart, Arteries and Veins. 7th ed. MacGraw-Hill, New York. Vol. 65, pp. 1278–1374.

Maron BJ, Wolfson JK, Epstein SE, Roberts WC. (1986) Intramural (“small vessel”) coronary artery disease in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 8: 545–557.

Smith ER, Heffernan LP, Sangalang VE, Vaughan LM, Flemington CS. (1976) Voluntary muscle involvement in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. A study of eleven patients. Ann. Intern. Med. 85: 566–572.

Fananapazir L, Dalakas MC, Cyran F, Cohn G, Epstein ND. (1993) Missense mutations in the β-myosin heavy-chain gene cause central core disease in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90: 3993–3997.

Schwartz K, de la Bastie D, Bouveret P, Oliviero P, Alonso S, Buckingham M. (1986) α-Skeletal muscle actin mRNA’s accumulate in hypertrophied adult rat hearts. Circ. Res. 59: 551–555.

Boheler KR, Carrier L, de la Bastie D, et al. (1991) Skeletal actin mRNA increases in the human heart during ontogenic development and is the major isoform of control and failing human hearts. J. Clin. Invest. 88: 323–330.

McKenna WJ, Stewart JT, Nihoyannapoulos P, McGinty F, Davies MJ. (1990) Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy without the hypertrophy: Two families with myocardial disarray in the absence of increased myocardial mass. Br. Heart. J. 63: 287–290.

Nishi H, Kimura A, Adachi K, Koga Y, Sasazuki T, Toshima H. (1994) Possible gene dose effect of a mutant cardiac β-myosin heavy chain on the clinical expression of familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 200: 549–556.

ten Cate FG, Roelandt J. (1979) Progression to left ventricular dilatation in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am. Heart J. 97: 762–765.

Fujiwara H, Onoder T, Tanaka M. (1984) Progression from hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy to typical dilated cardiomyopathy. Jpn. Circ. J. 48: 1210–1214.

Spirito P, Maron BJ, Bonow RO, Epstein SE. (1987) Occurrence and significance of progressive left ventricular wall thinning and relative cavity dilatation in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am. J. Cardiol. 59: 123–129.

Hecht GM, Klues HG, Roberts WC, Maron BJ. (1993) Coexistence of sudden cardiac death and end-stage heart failure in familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 22: 489–497.

Jackson T, Allard MF, Sreenan CM, Doss LK, Bishop SP, Swain JL. (1991) Transgenic animals as a tool for studying the effect of the c-myc proto-oncogene on cardiac development. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 104: 15–19.

Hunter JJ, Tanaka N, Rockman HA, Ross Jr J, Chien KR. (1996) Ventricular expression of a MLC-2v-ras fusion gene induces cardiac hypertrophy and selective diastolic dysfunction in transgenic mice. J. Biol. Chem. 270: 23173–23178.

Gruver CL, DeMayo F, Goldstein MA, Means AR. (1993) Targeted developmental overexpression of calmodulin induces proliferative and hypertrophic growth of cardiomyocytes in transgenic mice. Endocrinology 133: 376–388.

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported by a grant-in-aid from the New York Heart Association and the receipt of a National Institutes of Health (NIH) merit award (LAL). KLV was supported by the Sammy Davis, Jr., Neuromuscular Disease Post-Doctoral Fellowship from the Muscular Dystrophy Association and subsequently by a NIH training grant (PHS5T32HL07271). The authors would like to thank Dr. Glenn Fishman for assembling the full-length α Myh cDNA and Dr. Tom Harris for his instruction in producing transgenic mice. The authors also thank Dr. Doug Robertson for his advice on statistical analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vikstrom, K.L., Factor, S.M. & Leinwand, L.A. Mice Expressing Mutant Myosin Heavy Chains Are a Model for Familial Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Mol Med 2, 556–567 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03401640

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03401640