Abstract

This paper investigates the determinants of self-employment survival among women and men using the Canadian Survey of Labour and Income Dynamics. Survival is analyzed in the context of a single outcome (exiting self-employment) and in the context of multiple outcomes or competing risks (i.e. self-employment exit due to failure, versus non-failure exits). The largest detriment to survival for women is number of children. Whereas children improve survival rates for men. Non-participation in the labor force prior to starting a self-employment spell increases the probability of failure for women, but not men. Consistent with the liquidity constraint hypothesis, women who have personal wealth are less likely to exit self-employment. For women, this wealth effect does not depend on exit type. However, for men, the availability of personal wealth reduces the probability of exiting self-employment due to failure, but increases the probability of non-failure exits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

During the 1980s approximately 30 percent of self-employed were women. Author’s calculations using the Canadian Labour Force Survey.

Lin et al. (2000) report separate ln(exit rate) of 3.178 for female and 2.936 for male self-employed.

Several studies, in Canada and abroad, suggest that personal and business characteristics can explain most of this gender gap (e.g., Fabowale et al. 1995; Haines et al. 1999; Coleman 2000; and Blanchflower et al. 2003). However, there are two reasons to question the validity of these findings. First, the majority of these studies use survey data composed of business owners only. Such data cannot account for differences in rejection rates among individuals who applied for loans, but ended up not starting a business. Studies which use proprietary bank data, like Haines et al. (1999), may still be biased because, as Blanchflower et al. (2003) suggest, loan rejection gaps will be underestimated if minority (female) application rates are low from fear of rejection. As an example, Coleman (2000) finds that only 35 percent of female business owners applied for external funding, versus 45 percent of men. Evans and Jovanovic (1989) suggest that binding liquidity constraints can inhibit both entry and success in self-employment. Thus, poorer access to capital may be behind at least some of the gender differences in self-employment exit rates. Indeed, Fairlie and Robb, 2009 find that lower amounts of start-up capital among women can account for over 40 percent of the gender gap in business closure rates in the United States.

The regions are Eastern, Ontario, Quebec, Prairies, and BC. Ontario is omitted.

5 One benefit of the panel data is that the values of explanatory variables can be taken from the year prior to a spell start, mitigating the issue of endogenous personal characteristics. If these values were taken during the spell and an exit probit performed, then business success could be determining both the characteristics and exit probability.

Hurst and Lusardi (2004) find that the lowest quantile of low capital industries start with an average of $3,155. This information is derived from the National Survey of Small Business Finances (1987) and is converted to 1996 U.S. dollars. The equivalent amount in Canadian dollars is in the range of $4,264.

There are several different methods by which the literature measures liquidity constraints. Consistent with the literature I apply the term liquidity loosely as any measure of funds from which the individual may draw to start a business. Although liquidity and wealth are used interchangeably, it should also be noted that wealth measures are not entirely liquid. Wealth includes housing assets, which may be used as collateral, or sold for funds, but are not necessarily a preferred method for generating start-up capital. Moreover, liquidity and liquidity constraints have slightly different meanings. While ownership of liquidity implies the absence of constraints, a proxy for constraints need not be a quantitative measure of liquidity. For example, an alternative proxy for the presence of liquidity could be an indicator for withdrawal of retirement savings.

However, Fairlie (1999), analyzing self-employment entry across race, interprets the larger positive coefficient estimate for blacks (relative to whites) as indicative that credit market discrimination may exist.

However, the characteristics associated with a particular job, are the characteristics of the person in the year prior to the start of this specific job.

I classify jobs by the respondents self-report; however, some self-employment may be less serious than others. Some entrepreneurs have multiple jobs, and have businesses lasting less than one month. Short spells cannot be distinguished as failures or planned contract work. As such, I do not pre-condition my measure of self-employment status on duration or success. This definition is similar, in spirit, to that of Hurst and Lusardi (2004).

The majority of unknown ends occur at the termination of the Panel. However, 16–18 percent are truly unknown. Such ends may occur if subsequent interviewees deny the existence of a job (for example, a proxy respondent may not be aware of a job spell).

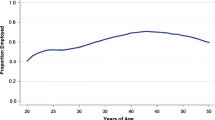

The Kaplan-Meier curve, survivor function, shows the conditional probability of an agent surviving time t, given that they reach time t.

Prior to inference using proportional hazard estimates, one should first confirm that the impact of characteristics is indeed constant (proportional). Two tests are run to consider the proportionality of the investment variable: plotting the observed against the predicted hazard, and plotting the -ln(-ln(survival)) curves at each value of the investment income 200 + flag. Adjusting for other covariates, both tests indicates that the proportional hazards is not violated.

The benefits to more restrictive samples is that interpretation is cleaner on a more homogeneous sample. The drawback to restricted samples, and novel proxies for liquidity constraints as well, is that the samples can become quite small. In some cases, the sample may be too small to obtain precise estimates and the external validity of the results on small samples is questionable.

Because there is no reason to suppose that the amount of capital necessary to propel a person to become self-employed is the same amount of capital that would enable them to survive, I also test a lower cut off of $100 in investment income. Hazard ratios are similar: larger than 1 for men, smaller than 1 for women, and both insignificant. Although the cell sizes are limited, I further test the non-linearity effect of liquidity on duration by using a series of investment income indicator variables. For the full sample, all categories are insignificant for men, while women have significant coefficients at 200–299 and over 5000. However, when missing values are dropped, the lower ranges 100, 200(peak for women) and 400 become more significant, and 5000 much less so.

Jenkins’ (2006) Hshaz and (2008) pgmhaz are used for the Heckman-Singer approach and for the discrete proportional hazards (Prentice-Gloeckler) model. Alternative specifications and starting values for two mass points are considered in the Heckman-Singer approach. Note that a reduced covariate list and a more aggregated baseline hazard (measured in one year intervals, merged for years 5 and 6) were necessary in order to estimate duration dependence as well as unobserved heterogeneity.

References

Blanchflower DG, Levine PB, Zimmerman DJ (2003) Discrimination in the Market for Small Business Credit Market. Rev Econ Stat 85(4):930–943

Blanchflower DG, Oswald A (1998) What Makes an Entrepreneur? J Labor Econ 16(1):26–60

Bates T (1990) Entrepreneur Human Capital Inputs and Small Business Longevity. Rev Econ Stat 72(4):551–559

Bruce D (1999) Do Husbands Matter? Married Women Entering Self-Employment. Small Bus Econ 13(4):317–329

Buttner EH, Rosen B (1992) Rejection in the Loan Application Process: Male and Female Entrepreneur’s Perceptions and Subsequent Intentions. J Small Bus Manag 30(1):58–65

Canadian Federation of Independent Business (1995). Financing Double Standard, Report. http://www.cfib.ca/research/reports/financin.asp, accessed July 27, 2006

Clain SH (2000) Gender Differences in Full-Time Self-Employment. J Econ Bus 52:499–513

Cliff JE (1998) Does One Size Fit All? Exploring the Relationship Between Attitudes Towards Growth, Gender, and Business Size. J Bus Ventur 13:523–542

Coleman S (2000) Access to Capital and Terms of Credit: A Comparison of Men- and Women-Owned Small Businesses. J Small Bus Manag 38(3):37–52

Cowling M, Taylor M (2001) Entrepreneurial Men and Women: Two Different Species? Small Bus Econ 16(3):167–175

Cox D (1972) Regression models and life tables (with discussion). Suppl J R Stat Soc B 34:187–220

Cressy R (1999) The Evans Jovanovic Equivalence Theorem and Credit Rationing: Another Look. Small Bus Econ 12:295–297

Dunn T, Holtz-Eakin D (2000) Financial Capital, Human Capital, and the Transition to Self-Employment: Evidence from Intergenerational Links. J Labor Econ 18(2):282–305

Evans DS, Jovanovic B (1989) An Estimated Model of Entrepreneurial Choice under Liquidity Constraints. J Polit Econ 97(4):808–827

Evans DS, Leighton LS (1989) Some Empirical Aspects of Entrepreneurship. Am Econ Rev 79(3):519–535

Fabowale L, Orser B, Riding A (1995) Gender, Structural Factors, and Credit Terms between Canadian Small Businesses and Financial Institutions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 19(4):41–65

Fairlie RW (1999) The Absence of African American Owned Business: An Analysis of the Dynamics of Self-Employment. J Labor Econ 17(1):80–108

Fairlie RW, Robb AM (2007) Why Are Black-Owned Businesses Less Successful than White-Owned Businesses? The Role of Families, Inheritances, and Business Human Capital. J Labor Econ 25(2):289–323

Fairlie RW, Robb AM (2009) Gender differences in business performance. evidence from the Characteristics of business Owners survey Small business Economics, 33(4): 375–395. Springer

Georgellis Y, Wall HJ (2005) Gender Differences in Self-Employment. Int Rev Appl Econ 19(3):321–342

Haines G, Orser B, Riding A (1999) Myths and Realities: An Empirical Study of Banks and the Gender of Small Business Clients. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences 16(4):291–307

Haapanen M, Tervo H (2009) Self-employment duration in urban and rural locations. Appl Econ 41(19):2449–2461

Heckman J, Singer B (1984) A Method for Minimizing the Impact of Distributional Assumptions in Econometric Models. Econometrica 52(2):271–320

Holtz-Eakin D, Joulfaian D, Rosen HS (1994a) Entrepreneurial Decisions and Liquidity ConstraintsRand. J Econ 25(2):334–337

Holtz-Eakin D, Joulfaian D, Rosen HS (1994b) Sticking it Out: Entrepreneurial Survival and Liquidity Constraints. J Polit Econ 102(1):53–75

Hundley G (2000) Male/Female Earnings Differences in Self-Employment: The Effects of Marriage, Children and the Household Division of Labor. Ind Labor Relat Rev 54(1):95–114

Hurst E, Lusardi A (2004) Liquidity Constraints, Household Wealth, and Entrepreneurship. J Polit Econ 112(2):319–347

Industry Canada (2003). SME Financing in Canada. http://www.ic.gc.ca/epic/site/sme_fdi-prf_pme.nsf/en/h_01565e.html. Accessed August 10, 2008

Jenkins SP (2005) Survival Analysis. Unpublished manuscript, Institute for Social and Economic Research, University of Essex, Colchester

Jenkins SP (2006) HSHAZ Stata module to estimate discrete time (grouped data) proportional hazards models. Statistical Software Components Series S444601, Boston College Department of Economics, Chestnut Hill

Jenkins S (2008) Estimation of discrete time (grouped duration data) proportional hazards models: pgmhaz. http://www.iser.essex.ac.uk/teaching/degree/stephenj/ec968/pdfs/STB-39-pgmhaz.pdf. Accessed May, 2008

Jianakoplos NA, Bernasek A (1998) Are Women More Risk Averse? Econ Inq 36(4):620–630

Kan K, Tsai W-D (2006) Entrepreneurship and Risk Aversion. Small Bus Econ 26:465–474

Khun P, Schuetze H (2001) Self-Employment Dynamics and Self-Employment Trends: A Study of Canadian Men and Women, 1982-1998. Can J Econ 34(3):760–784

Lin Z, Picot G, Compton J (2000) The Entry and Exit Dynamics of Self-Employment in Canada. Small Bus Econ 15(2):105–125

Moore CS, Mueller RE (2002) The Transition from Paid to Self-Employment in Canada: The Importance of Push Factors. Appl Econ 34(6):791–801

Millán J-M, Congregado E, Romn C (2010) Determinants of self-employment survival in Europe. Small Bus Econ 38(2):231–258

Prentice R, Gloeckler L (1978) Regression analysis of grouped survival data with application to breast cancer data. Biometrics 34:57–67

Prime Minister’s Task Force (2003) The Prime Minister’s Task Force on Women Entrepreneurs Report and Recommendations. http://sen.parl.gc.ca/ccallbeck/Canada_Prime_Ministers_Task_Force_Report-en.pdf. accessed February 18, 2014

Rybczynski K (2013) Self-Employment Entry: Revisiting the Question of Liquidity. SWO-RDC working paper #1361

Schuetze H (2005) The Self-Employment Experience of Immigrants in Canada. mimeo. University of Victoria. http://web.uvic.ca/hschuetz/immigse3.pdf. Accessed Sept. 13, 2006

Schuetze H (2006) Income Splitting among the Self-Employed. Can J Econ 39(4):1195–1220

Taylor M (1999) Survival of the Fittest? An Analysis of Self-Employment Duration in Britain. Econ J 109 (March):140–155

Treichel MZ, Scott JA (1987) Women-Owned Businesses and Access to Bank Credit. Evidence from Three Surveys Since. Ventur Cap 8(1):51–67

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The research and analysis in this paper are based on data from Statistics Canada. The opinions expressed herein do not represent the views of Statistics Canada.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rybczynski, K. What Drives Self-Employment Survival for Women and Men? Evidence from Canada. J Labor Res 36, 27–43 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12122-014-9194-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12122-014-9194-4