Abstract

The present study investigates the frequency and functions of vague expressions (e.g. something, sort of) used in the 2016 U.S. presidential debates by Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump. The data under scrutiny include transcripts of the televised debates (42,137 words). The study reveals that, while Trump’s speech is less lexically varied than Clinton’s, it contains a noticeably greater number of vague expressions. Trump’s tendency to use more instances of vague language is most evident in the categories of ‘vague boosters’ (e.g. very), ‘vague estimators’ (e.g. many), ‘vague nouns’ (e.g. things) and ‘vague extenders’ (e.g. and other places). Clinton, however, more frequently uses ‘vague subjectivisers’ (e.g. I think) and ‘vague possibility indicators’ (e.g. would). The differences observed may be attributed to the personal and professional backgrounds of the candidates and to the different communicative purposes they seek to achieve.

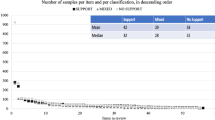

(motivated by and adapted from Zhang 2015, p. 62)

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For a definition of vague language, see next section.

The original sorites paradox would be a classic example of vagueness as discussed in philosophy. If “the removal of one grain from a heap always leaves a heap, then the successive removal of every grain still leaves a heap” (Williamson 1994, p. 4). Indeed, the word heap is vague because we cannot precisely explain where the boundary between a heap and a non-heap is to be found.

Due to reasons of space, in this paper a complete list of vague expressions considered is not provided.

I am aware that, given the high-stake nature of the debates in question in which people may need precision rather than imprecision, some people may consider a vague noun such as ‘thing’, as used in 'the one thing you have over me' being uttered by a presidential candidate, to be inappropriate. However, we are not at this stage in a position to judge which expression would be more appropriate.

References

Adolphs, S., Atkins, S., & Harvey, K. (2007). Caught between professional requirements and interpersonal needs: Vague language in healthcare contexts. In J. Cutting (Ed.), Vague language explored (pp. 62–78). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Ahmadian, S., Azarshahi, S., & Paulhus, D. L. (2017). Explaining Donald Trump via communication style: Grandiosity, informality, and dynamism. Personality and Individual Differences, 107, 49–53.

Bavelas, J. B., Black, A., Chovil, N., & Mullett, J. (1990). Equivocal communication. London: Sage Publications.

Benoit, W. L., McKinney, M. S., & Lance Holbert, R. (2001). Beyond learning and persona: Extending the scope of presidential debate effects. Communication Monographs, 68(3), 259–273.

Berndt, R. S., & Caramazza, A. (1978). The development of vague modifiers in the language of pre-school children. Journal of Child Language, 5(02), 279–294.

Boakye, N. G. (2007). Aspects of vague language use: Formal and informal contexts. Unpublished MA thesis, University of South Africa.

Bradac, J. J., Mulac, A., & Thompson, S. A. (1995). Men’s and women’s use of intensifiers and hedges in problem-solving interaction: Molar and molecular analyses. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 28(2), 93–116.

Bull, P. (2008). “Slipperiness, evasion, and ambiguity”: Equivocation and facework in noncommittal political discourse. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 27(4), 333–344.

Capone, A. (2010). Barack Obama’s South Carolina speech. Journal of Pragmatics, 42, 2964–2977.

Carter, R. (2003). The grammar of talk: Spoken English, grammar and the classroom. In New perspectives on English in the classroom (pp. 5–13). London: Qualifications and Curriculum Authority.

Carter, R., & McCarthy, M. (2006). Cambridge grammar of English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Channell, J. (1994). Vague language. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cheng, W. (2007). The use of vague language across spoken genres in an intercultural Hong Kong corpus. In J. Cutting (Ed.), Vague language explored (pp. 161–181). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Cheng, W., & O’Keeffe, A. (2014). Vagueness. In C. Rühlemann & K. Aijmer (Eds.), Corpus pragmatics: A handbook (pp. 360–379). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cheng, W., & Warren, M. (2003). Indirectness, inexplicitness and vagueness made clearer. Pragmatics, 13, 381–400.

Cheshire, J. (2007). Discourse variation, grammaticalisation and stuff like that. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 11(2), 155–193.

Conway, L. G., Gornick, L. J., Burfeind, C., Mandella, P., Kuenzli, A., Houck, S. C., et al. (2012). Does complex or simple rhetoric win elections? An integrative complexity analysis of US presidential campaigns. Political Psychology, 33(5), 599–618.

Corcoran, P. E. (1990). Language and politics. In D. L. Swanson & D. Nimmo (Eds.), New directions in political communication: A resource book (pp. 51–85). London: Sage.

Crystal, D., & Davy, D. (1975). Advanced conversational English. London: Longman Publishing Group.

Cutting, J. (2007a). Introduction to ‘vague language explored’. In J. Cutting (Ed.), Vague language explored (pp. 3–20). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Cutting, J. (Ed.). (2007b). Vague language explored. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Cutting, J. (2007c). Doing more stuff—Where’s it going?: Exploring vague language further. In J. Cutting (Ed.), Vague language explored (pp. 223–243). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Cutting, J. (2012). Vague language in conference abstracts. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 11(4), 283–293.

Cutting, J. (2015). Dingsbums und so: Beliefs about German vague language. Journal of Pragmatics, 85, 108–121.

D’Errico, F., Vincze, L., & Poggi, I. Vagueness in political discourse. (2013). Manuscript retrievable from http://www.comunicazione.uniroma3.it/UserFiles/File/Files/1403_Political%20Vagueness_Final_Resub.pdf.

Dines, E. (1980). Variation in discourse and stuff like that. Language in Society, 1, 13–31.

Dörnyei, Z. (2007). Research methods in applied linguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Drave, N. (2000). Vaguely speaking: A corpus approach to vague language in intercultural conversations. In P. Peters, P. Collins, & A. Smith (Eds.), Language and computers: New frontiers of corpus research. Papers from the Twenty-First International Conference of English Language Research and Computerized Corpora (pp. 25–40). The Netherlands: Rodopi.

Drave, N. (2001). Vaguely speaking: A corpus approach to vague language in intercultural conversations. Language and Computers, 36(1), 25–40.

Ediger, A. (1995). Joanna Channell: Vague Language (Book Review). Applied Linguistics, 16(1), 127.

Fernández, J. (2015). General extender use in spoken Peninsular Spanish: metapragmatic awareness and pedagogical implications. Journal of Spanish Language Teaching, 2(1), 1–17.

Fernández, J., & Yuldashev, A. (2011). Variation in the use of general extenders and stuff in instant messaging interactions. Journal of Pragmatics, 43(10), 2610–2626.

Gassner, D. (2012). Vague language that is rarely vaguep: A case study of “thing” in L1 and L2 discourse. International Review of Pragmatics, 4(1), 3–28.

Holmes, J. (1988). ‘Sort of’ in New Zealand women’s and men’s speech. Studia Linguistica, 42(2), 85–121.

Holmes, J. (1990). Hedges and boosters in women’s and men’s speech. Language & Communication, 10(3), 185–205.

Holmes, J. (1995). Men, women and politeness. London: Longman.

Hu, G., & Cao, F. (2011). Hedging and boosting in abstracts of applied linguistics articles: A comparative study of English- and Chinese-medium journals. Journal of Pragmatics, 43, 2795–2809.

Hyland, K. (1998). Hedging in scientific research articles. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing.

Hyland, K. (2000). Hedges, boosters and lexical invisibility: Noticing modifiers in academic texts. Language Awareness, 9(4), 179–197.

Hyland, K. (2005). A model of interaction in academic discourse. Discourse Studies, 7, 173–192.

Irvine, J. T. (1979). Formality and informality in communicative events. American Anthropologist, 81(4), 773–790.

Izadi, D., & Parvaresh, V. (2016). The framing of the linguistic landscapes of Persian shop signs in Sydney. Linguistic Landscape, 2(2), 182–205.

Janney, R. (2002). Cotext as context: Vague answers in court. Language & Communication, 22, 457–475.

Johnson, R. B., Onwuegbuzie, A. J., & Turner, L. A. (2007). Toward a definition of mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1(2), 112–133.

Jucker, A. H., Smith, S. W., & Ludge, T. (2003). Interactive aspects of vagueness in conversation. Journal of Pragmatics, 35, 1737–1769.

Kecskes, I. (2014). Intercultural pragmatics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Koester, A. (2007). “About twelve thousand or so”: Vagueness in north American and UK offices. In J. Cutting (Ed.), Vague language explored (pp. 40–61). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Li, S. (2017). A corpus-based study of vague language in legislative texts: Strategic use of vague terms. English for Specific Purposes, 45, 98–109.

Malouf, R., & Mullen, T. (2008). Taking sides: User classification for informal online political discourse. Internet Research, 18(2), 177–190.

Mauranen, A. (2004). ‘They’re a little bit different’. Observations on hedges in academic talk. In K. Aijmer & A. Stenström (Eds.), Discourse patterns in spoken and written corpora (pp. 173–198). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

McEnery, T., & Hardie, A. (2012). Corpus linguistics: Method, theory and practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Metsä-Ketelä, M. (2016). Pragmatic vagueness: Exploring general extenders in English as a lingua franca. Intercultural Pragmatics, 13(3), 325–351.

Mey, J. L. (2017). Corpus linguistics: Some (meta-) pragmatic reflections. Corpus Pragmatics, 1, 185–199.

Murphy, B. (2010). Corpus and sociolinguistics: Investigating age and gender in female talk. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing.

Obeng, S. G. (1997). Language and politics: Indirectness in political discourse. Discourse & Society, 8(1), 49–83.

Overstreet, M. (1999). Whales, candlelight, and stuff like that: General extenders in English discourse. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Overstreet, M. (2011). Vagueness and hedging. In G. Andersen & K. Aijmer (Eds.), Pragmatics of society (pp. 293–317). Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

Parvaresh, V. (2015). Vague language that is vaguep in both L1 and L2: A comment on Gassner (2012). International Review of Pragmatics, 7(1), 129–143.

Parvaresh, V. (2017a). Panegyrists, vagueness and the pragmeme. In V. Parvaresh & A. Capone (Eds.), The pragmeme of accommodation: The case of interaction around the event of death (pp. 61–81). Cham: Springer.

Parvaresh, V. (2017b). Book review: Grace Q Zhang, Elastic language: How and why we stretch our words. Discourse Studies, 19(1), 115–117.

Parvaresh, V., & Ahmadian, M. J. (2016). The impact of task structure on the use of vague expressions by EFL learners. The Language Learning Journal, 44(4), 436–450.

Parvaresh, V., Tavangar, M., Rasekh, A. E., & Izadi, D. (2012). About his friend, how good she is, and this and that: General extenders in native Persian and non-native English discourse. Journal of Pragmatics, 44(3), 261–279.

Parvaresh, V., & Tayebi, T. (2014). Vaguely speaking in Persian. Discourse Processes, 51(7), 565–600.

Pierce, C. S. (1902). Vagueness. In M. Baldwin (Ed.), Dictionary of philosophy and psychology II. London: Macmillan.

Powell, M. (1985). Purposive vagueness: An evaluative dimension of vague quantifying expressions. Journal of Linguistics, 21, 31–50.

Rowland, T. (2007). ‘Well maybe not exactly, but it’s around fifty basically?’: Vague language in mathematics classrooms. In J. Cutting (Ed.), Vague language explored (pp. 79–96). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Rue, Y., & Zhang, G. (2008). Request strategies: A comparative study in Mandarin Chinese and Korean. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Ruzaitė, J. (2007). Vague language in educational settings: Quantifiers and approximators in British and American English. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

Sabet, P., & Zhang, G. (2015). Communicating through vague language: A comparative study of L1 and L2 speakers. London: Palgrave.

Shirato, J., & Stapleton, P. (2007). Comparing English vocabulary in a spoken learner corpus with a native speaker corpus: Pedagogical implications arising from an empirical study in Japan. Language Teaching Research, 11(4), 393–412.

Sobrino, A. (2015). Inquiry about the origin and abundance of vague language: An issue for the future. Towards the future of fuzzy logic (pp. 117–136). Cham: Springer.

Stubbe, M., & Holmes, J. (1995). You know, eh and other ‘exasperating expressions’: An analysis of social and stylistic variation in the use of pragmatic devices in a sample of New Zealand English. Language & Communication, 15(1), 63–88.

Stubbs, M. (1986). A matter of prolonged field work: Notes towards a modal grammar of English. Applied Linguistics, 7, 1–25.

Suedfeld, P. (1992). Cognitive managers and their critics. Political Psychology, 13, 435–453.

Suedfeld, P., & Rank, A. D. (1976). Revolutionary leaders: Long-term success as a function of changes in conceptual complexity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 34, 169–178.

Tagliamonte, S. A., & Denis, D. (2010). The stuff of change: General extenders in Toronto. Canada. Journal of English Linguistics, 38(4), 335–368.

Tayebi, T., & Parvaresh, V. (2014). Conversational disclaimers in Persian. Journal of Pragmatics, 62, 77–93.

Terraschke, A. (2013). A classification system for describing quotative content. Journal of Pragmatics, 47(1), 59–74.

Thomson, D. (2016). Trump vs. Clinton: A battle between two opposite Americas. The Atlantic. Last retrieved on 12 Feb 2016 from https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2016/04/clinton-trump/480162/.

Tomasello, M. (2003). The key is social cognition. In D. Gentner & S. Goldin-Meadow (Eds.), Language in mind (pp. 43–58). Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Williamson, T. (1994). Vagueness. London: Routledge.

Zhang, G. (2011). Elasticity of vague language. Intercultural Pragmatics, 8, 571–599.

Zhang, G. (2013). The impact of touchy topics on vague language use. Journal of Asian Pacific Communication, 23, 87–118.

Zhang, G. (2015). Elastic language: How and why we stretch our words. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Zhang, G. (2016). How elastic a little can be and how much a little can do in Chinese. Chinese Language and Discourse, 7(1), 1–22.

Zhang, G., & Sabet, P. G. (2016). Elastic ‘I think’: Stretching over L1 and L2. Applied Linguistics, 37(3), 334–353.

Acknowledgements

I wish to express my gratitude to the anonymous reviewers from Corpus Pragmatics who went through earlier versions of this paper and made very insightful comments and suggestions with a view to improving its quality. I am also indebted to Tahmineh Tayebi for her help and advice. I take sole responsibility for any remaining inadequacies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Top 10 vague expressions across the debates

Clinton Debate 1 | Trump Debate 1 | Clinton Debate 2 | Trump Debate 2 | Clinton Debate 3 | Trump Debate 3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Item | Freq. per 1000 | Item | Freq. per 1000 | Item | Freq. per 1000 | Item | Freq. per 1000 | Item | Freq. per 1000 | Item | Freq.per 1000 |

I think | 6.03 | Very | 8.08 | I think | 4.83 | Very | 4.44 | I think | 4.98 | Very | 5.99 |

Would | 5.11 | Thing(s) | 4.66 | Would | 4.03 | Thing(s) | 4.16 | Would | 3.51 | So | 4.79 |

More | 3.40 | I think | 3.86 | Very | 3.86 | So | 3.33 | Very | 2.78 | Many | 3.14 |

Really | 3.09 | Many | 3.18 | A lot of | 3.70 | Would | 2.77 | More | 2.19 | Would | 3.14 |

Thing(s) | 2.32 | So | 2.50 | More | 2.41 | Many | 2.22 | Really | 1.75 | I think | 3.14 |

A lot of | 2.16 | Would | 2.16 | Some | 2.25 | More | 1.80 | Some | 1.46 | Much | 2.69 |

So | 2.01 | Really | 2.16 | Something | 1.61 | I think | 1.80 | Could | 1.02 | Thing(s) | 2.54 |

Many | 1.85 | Some | 2.04 | Maybe | 1.28 | A lot of | 1.52 | Just | 1.02 | Millions | 1.79 |

Some | 1.85 | Much | 2.04 | Really | 1.12 | Something | 1.52 | I believe | 1.02 | More | 1.64 |

Very | 1.85 | More | 1.36 | Anyone | 1.12 | Really | 1.38 | Many | 0.87 | Some | 1.28 |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Parvaresh, V. ‘We Are Going to Do a Lot of Things for College Tuition’: Vague Language in the 2016 U.S. Presidential Debates. Corpus Pragmatics 2, 167–192 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41701-017-0029-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41701-017-0029-4