Abstract

Using the Cambodia Socio-Economic Survey 2011, this study is to quantify the impacts of disabilities induced by armed conflicts on poverty. Two main empirical findings emerge: First, disabilities aggravate poverty by 12–15%. Especially, disabilities caused by war and land mines exacerbate poverty significantly by 26–27%. In contrast, congenital disabilities or disabilities caused by accidents and diseases do not generate significant impact on poverty. Second, household characteristics, such as the number of household members, residential area, education, and marriage status of household head, are systematically correlated with poverty.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Roberts (2011, pp.167–183) lists diverse origins of Cambodia’s mine/UXO. First, the origin of Cambodia’s mines goes back to the US carpet bombing during the Vietnam War (1965–1979). Second, the Royal Government of Cambodia deployed mines to resist Khmer Rouge’s attacks on major cities (1971–1975). Third, with support from the North Vietnam and the Soviet Union, Khmer Rouge deployed mines to preserve its power and to protect its national borders. Fourth, since 1968, Thailand and Cambodia competitively deployed mines to protect their national borders. Finally, after the fall of the Khmer Rouge regime, the People’s Republic of Kampuchea that was under the control of Vietnam deployed explosives for protection of the country’s borders.

The healthcare system in Cambodia has improved with the support of the WHO since the Health Sector Reform in 1995 (DPHI and MOH 2007, pp. 9–10). Since 2003, the Health Sector Support Project of the World Bank has been assisting Cambodia with improving accessibility and quality of its healthcare system (World Bank, 2013). Yet, the quality of the healthcare system is undermined, and the share of health centers that provides full minimum services was 43% (WHO and MOH 2012, p. 2).

There is limited access to objective information on the socio-economic status of people with disabilities in developing countries. As a result, unlike in advanced nations, it is not easy to evaluate how successful inclusive development policies are in reducing poverty among people with disabilities (Lamichhane and Sawada 2013, p. 85).

Depending on publications and methodology, the share of disabled people in adults ranges from 1.5 to 15% of the population (Thomas 2005, p. 21), and as low as 2% or as high as 15% of Cambodia’s total population are disabled (Zook 2010, p. 51). Nevertheless, Cambodia has one of the highest rates of disability in the developing world (UN ESCAP 2002).

Before examining the relationship between disability and poverty, it is imperative to review the definition of disability. Disability has been regarded as an individual issue and merely as the consequence of certain dysfunctional body parts in the medical perspective. However, under a new definition or a social model of disability, it is deemed that society categorizes people with dysfunctional body parts as disabled (Matsui et al. 2012). Disability, therefore, arises from complex interaction between health conditions and the context in which they exist (Mont 2007, p. 4).

Refer to ILO (2017) for detailed information regarding the calculation method.

This study employed STATA (ver. 13) to estimate the econometric models.

It remains a question as to which is a more proper variable: income or consumption. Under life-cycle or permanent income hypothesis, a consumption fluctuates relatively less than income does over the course of time, and therefore, consumption variable is more appropriate to measure individual welfares (Kang et al. 2013, p. 6).

To control for the differences arising from the characteristics of each region, the average values of observations belonging to the same villages were subtracted from each observation and a regression analysis was conducted.

There are 660 households in the highest 25% region, and among them, 79 households have disabled heads. In the highest 25% region, the proportion of households with disabled heads to total households is 11.97%. There are 1315 households in the lowest 25% region, and among them, 103 households have disabled heads. In the lowest 25% region, the proportion of households with disabled heads to total households is 7.83%.

Refer to Appendix Table 1 for the balancing test results for determining if PSM was properly conducted.

According to results, there is only one treated sample which is not included in common support region.

An important thing is why PSM is used. Usually, PSM is used if samples are selected. The outcome suggests that there is a gap between the average consumption of the two groups even when samples are selected. Covariates of propensity score estimates reveal that the treatment group and control comparison group are properly balanced with the propensity score. That is, compared to the raw score, the mean bias of the matched sample decreased from 31.5 to 3.5 and the median bias decreased from 19.8 to 2.7.

Refer to the webpage of the Cambodian Mine Action Center (2017) for more details on mines and UXOs statistics (http://cmac.gov.kh/en/article/progress-summary-report.htm, retrieved on 25 June 2017).

References

Blattman C, Miguel E (2010) Civil War. J Econ Lit 48(1):3–57

Cambodian Mine Action Center [CMAC] (2017) CMAC’s Mine/UXO clearance achievement 1992-March 2014. http://cmac.gov.kh/en/article/progress-summary-report.html. Accessed 25 June 2017

Cambodian Mine Action and Victim Assistance Authority [CMAA] (2015) CMVIS monthly report October 2015, CMAA

Department of Planning and Health Information and Ministry of Health [DPHI and MOH] (2007) Cambodia health information system: review and assessment. http://www.moh.gov.kh/files/dphi/chisra.pdf. Accessed 15 May 2014

Filmer D (2008) Disability, poverty, and schooling in developing countries: results from 14 household surveys. World Bank Econ Rev 22(1):141–163

Graham N (2014) Children with disabilities. Paper commissioned for fixing the broken promise of education for all: findings from the global initiative on out-of-school children (UIS/UNICEF 2015). UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS), Montreal

International Campaign to Ban Landmines [ICBL] (2012) Landmine monitor 2012

International Labor Organization [ILO] (2017) Cambodian Socio-Economic Survey (CSES) 2011. ILO Microdata Repository

Japan Bank for International Cooperation [JBIC] (2001) Poverty profile executive summary: Kingdom of Cambodia. December, 2011

Kang SJ, Chung YW, Sohn SH (2013) The effects of monetary policy on individual welfares. Korea World Econ 14(1):1–29

Kenjiro Y (2005) Why illness causes more serious economic damage than crop failure in rural Cambodia. Dev Change 36(4):759–783

Lamichhane K, Sawada Y (2013) Disability and returns to education in a developing country. Econ Educ Rev 37:85–94

Matsui A, Nagase O, Sheldon A, Goodley D, Sawada Y, Kawashima S (2012) Creating a society for all: disability and economy. Disability Press, Leeds

Mitra S, Sambamoorthi U (2008) Disability and the rural labor market in India: evidence for males in Tamil Nadu. World Dev 36(5):934–952

Mitra S, Posarac A, Vick B (2011) Disability and poverty in developing countries—a snapshot from the World Health Survey, World Bank

Mizunoya S, Mitra S (2012) Is there a disability gap in employment rates in developing countries? World Dev 42:28–43

Mont D (2007) Measuring disability prevalence, social protection. World Bank

Mont D, Cuong NV (2011) Disability and Poverty in Vietnam. World Bank Econ Rev 25(2):323–359

National Institute of Statistics [NIS] (2013) Supplementary notes commenting the results of the Cambodia socio-economic survey, CSES 2012. National Institute of Statistics, Ministry of Planning, Cambodia

Palmer MG, Thuy NTM, Quyen QTN, Duy DS, Huynh HV, Berry HL (2012) Disability measures as an indicator of poverty: a case study from Viet Nam. J Int Dev 24:S53–S68

Roberts WC (2011) Landmines in Cambodia: past, present, and future. Cambria, Amherst, New York

Royal Government of Cambodia (2010) National mine action strategy (2010–2019). Royal Government of Cambodia

Thomas P (2005) Poverty reduction and development in Cambodia: enabling disabled people to play a role, disability KAR

United Nations Development Programme [UNDP] (2011) Human Development Report 2011—sustainability and equity: a better future for all. UNDP

United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific [UN ESCAP] (2002) Pathfinders: towards full participation and equality of persons with disabilities in the ESCAP region. UNESCAP, Bangkok

World Bank (2013) Cambodia: health sector support project. http://go.worldbank.org/4ACCSBTHR0. Accessed 15 May 2014

World Bank (2014) Poverty Headcount Ratio at Rural Poverty Line (% of rural population), World Development Indicators, World Bank. http://data.worldbank.org/country/cambodia. Accessed 8 Aug 2014

World Health Organization and Ministry of Health [WHO and MOH] (2012) Health Service Delivery Profile: Cambodia 2012. http://www.wpro.who.int/health_services/service_delivery_profile_cambodia.pdf. Accessed 15 May 2014

Zook DC (2010) Disability and democracy in Cambodia: an integrative approach to community building and civic engagement. Disabil Soc 25(2):149–161

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

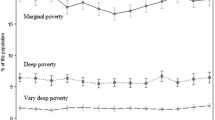

In line with the robustness check in Sect. 3, Appendix Table 8 shows the balancing test results if PSM is properly conducted. The average difference among independent variables of the treatment group and the control group is not statistically significant. Simply put, the average of independent variables of both groups is not different (Fig. 2).

About this article

Cite this article

Kang, S.J., Sawada, Y. & Chung, Y.W. Long-term consequences of armed conflicts on poverty: the case of Cambodia. Asia-Pac J Reg Sci 1, 519–535 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41685-017-0050-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41685-017-0050-4