Abstract

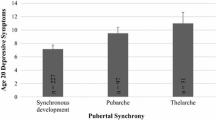

In spite of the large literature supporting the link between early pubertal timing and depression in adolescent girls, there are some exceptions. This suggests that there may be factors that interact with pubertal timing, increasing risk for depression in some girls, but not others. This study examined two such factors, romantic competence and romantic experiences, and their role in the cross-sectional and longitudinal associations between pubertal timing and depressive symptoms among 83 early adolescent females (89% Caucasian). For on-time maturing girls (but not for early- or late-), lower levels of competence were associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms concurrently, but not longitudinally. In addition, for on-time maturing girls, more romantic experiences were associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms both concurrently and longitudinally. The discussion focused on the need for greater conceptual and empirical clarity regarding the pubertal timing-depression association and its potential moderators.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

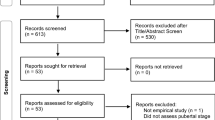

To ensure that an adequate amount of girls with depressive symptoms would participate, parents of girls with higher (22+) questionnaire study CES-D scores were contacted first; however, ultimately all parents of female questionnaire participants were contacted. There were no significant differences between girls recruited from the questionnaire study and from the school newsletter on T1 depressive symptoms, pubertal timing, romantic competence, family income, or ethnicity. Girls recruited from the questionnaire study had significantly more T1 relationship experiences (M = 23.73, SD = 4.98 versus M = 19.71, SD = 3.46; t(79) = 3.14, p < .05), most likely because depressive symptoms and relationship experiences were highly correlated.

In Petersen’s original article (Petersen et al. 1988), alpha coefficients ranged from .68 to .83 (mean = .77). In other studies using the PDS, alpha coefficients varied. Some report above .70 or .75 (Ge et al. 2001, 2003), but others report lower alphas. For instance, Dick et al. (2001) reported alpha for girls at age 12 of .67 and at age 14 of .56. Alpha in this study is consistent with these lower alphas at younger ages.

All interview questions in the RCI used non-biased language, using words such as ‘the person’ and ‘someone’ or giving both sexes (him or her, she or he), allowing for the possibility of same- or other-sex experiences. The MAHC is more heterosocial which is a limitation of this measure. Although we did not directly assess sexual orientation, on the RCI, the vast majority of girls spoke of heterosexual experiences, indicating that regardless of sexual orientation, the girls in this sample were familiar with the kinds of experiences assessed on the MAHC.

As is common when constructs are assessed using different methods (semi-structured interview for the RCI and self-report for the MAHC), correlations may be only modest. This certainly reflects that these variables have both shared and non-shared components. However, given that they have shared components and each measures important aspects of competence, we selected to create a composite variable.

Although sexual activity is a normative adolescent behavior, sexual activity is less frequent in early adolescence and thus, it is included here. For example, national statistics show that less than 4% of adolescent females engage in sexual intercourse before the age of 13 (National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, n.d.). Also we know that early sexual activity, particularly sexual intercourse and casual sex, are frequently associated with poorer psychosocial functioning, including depression (e.g., Welsh et al. 2003).

We examined the normative relationship experiences separately (to isolate them from non-normative experiences) because there was more variability in the normative experiences.

We also ran a one-way ANOVA to compare the 3 pubertal timing groups on T2 depressive symptoms, without controlling for T1 symptoms. The ANOVA was not significant, F(2, 71) = .894, p > .05.

We did not test these predicted interactions because we did not have the power to do so. Future work should address these predictions.

References

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage Publications, Inc.

Angold, A., Costello, E. J., & Worthman, C. M. (1998). Puberty and depression: The roles of age, pubertal status and pubertal timing. Psychological Medicine, 28, 51–61. doi:10.1017/S003329179700593X.

Angold, A., Worthman, C., & Costello, E. J. (2003). Puberty and depression. In C. Hayward (Ed.), Gender differences at puberty (pp. 137–164). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Brooks-Gunn, J., Petersen, A. C., & Eichorn, D. (1985). The study of maturational timing effects in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 14, 149–161. doi:10.1007/BF02090316.

Brooks-Gunn, J., Warren, M. P., Rosso, J., & Gargiulo, J. (1987). Validity of a self-report measures of girls’ pubertal status. Child Development, 58, 829–841. doi:10.2307/1130220.

Caspi, A., & Moffitt, T. E. (1991). Individual differences are accentuated during periods of social change: The sample case of girls at puberty. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 157–168. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.61.1.157.

Collins, W. A. (2003). More than myth: The developmental significance of romantic relationships during adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 13, 1–24. doi:10.1111/1532-7795.1301001.

Compain, L., Gowen, L. K., & Hayward, C. (2004). Peripubertal girls’ romantic and platonic involvement with boys: Associations with body image and depression symptoms. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 14, 23–47. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2004.01401002.x.

Compain, L., & Hayward, C. (2003). Gender differences in opposite sex relationships: Interactions with puberty. In C. Hayward (Ed.), Gender differences at puberty (pp. 77–92). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Connolly, J. A., & Goldberg, A. (1999). Romantic relationships in adolescence: The role of friends, peers in their emergence and development. In W. Furman, B. B. Brown, & C. Feiring (Eds.), The development of romantic relationships in adolescence (pp. 266–290). NY: Cambridge University Press.

Cyranowski, J. M., Frank, E., Young, E., & Shear, M. K. (2000). Adolescent onset of the gender difference in lifetime rates of major depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 57, 21–27. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.57.1.21.

Davila, J., & Steinberg, S. J. (2006). Depression and romantic dysfunction during adolescence. In T. Joiner, J. Brown, & J. Kistner (Eds.), The interpersonal, cognitive and social nature of depression (pp. 23–42). Mahwah, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Davila, J., Steinberg, S. J., Kachadourian, L., Cobb, R., & Fincham, F. (2004). Romantic involvement and depressive symptoms in early and late adolescence: The role of a preoccupied relational style. Personal Relationships, 11, 161–178. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6811.2004.00076.x.

Davila, J., Steinberg, S. J., Ramsay, M., Stroud, C. B., Starr, L., & Yoneda, A. (in press). Assessing romantic competence in adolescence: The Romantic Competence Interview. Journal of Adolescence.

Dick, D. M., Rose, R. J., Pulkkinen, L., & Kaprio, J. (2001). Measuring puberty and understanding its impact: A longitudinal study of adolescent twins. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 30, 385–399. doi:10.1023/A:1010471015102.

Dorn, L. D., Dahl, R. E., & Woodward, H. R. (2006). Defining the boundaries of early adolescence: A user’s guide to assessing pubertal status and pubertal timing in research with adolescents. Applied Developmental Science, 10, 30–56. doi:10.1207/s1532480xads1001_3.

Ellis, B. J., & Garber, J. (2000). Psychosocial antecedents of variation in girls’ pubertal timing: Maternal depression, stepfather presence, and marital and family stress. Child Development, 71, 485–501. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00159.

Flannery, D. J., Rowe, D. C., & Gulley, B. L. (1993). Impact of pubertal status, timing, and age on adolescent sexual experience and delinquency. Journal of Adolescent Research, 8, 21–40. doi:10.1177/074355489381003.

Furman, W., & Wehner, E. A. (1994). Romantic views: Toward a theory of adolescent romantic relationships. In R. Montmayer, G. R. Adams, & G. P. Gullota (Eds.), Advances in adolescent development: Volume 6, personal relationships during adolescence (pp. 168–175). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Ge, X., Conger, R. D., & Elder, G. H. (1996). Coming of age too early: Pubertal influences on girls’ vulnerability to psychological distress. Child Development, 67, 3386–3400. doi:10.2307/1131784.

Ge, X., Cogner, R. D., & Elder, G. H. (2001). Pubertal transition, stressful life events, and the emergence of gender differences in adolescent depressive symptoms. Developmental Psychology, 37, 404–417. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.37.3.404.

Ge, X., Kim, I. J., Brody, G. H., Conger, R. D., Simons, R. L., Gibbons, F. X., et al. (2003). It’s about timing and change: pubertal transition effects on symptoms of major depression among African American youths. Developmental Psychology, 39, 430–439. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.39.3.430.

Graber, J. A. (2003). Puberty in context. In C. Hayward (Ed.), Gender differences at puberty (pp. 307–325). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Graber, J. A., Brooks-Gunn, J., & Warren, M. P. (1995). Pubertal processes: Methods, measures, and models. In J. A. Graber, J. Brooks-Gunn, & A. C. Petersen (Eds.), Transitions through adolescence: interpersonal domains and context (pp. 25–53). Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Graber, J. A., Brooks-Gunn, J., & Warren, M. P. (2006). Pubertal effects on adjustment in girls: Moving from demonstrating effects to identifying pathways. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 35, 413–423. doi:10.1007/s10964-006-9049-2.

Graber, J. A., Lewinsohm, P. M., Seeley, J. R., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (1997). Is psychopathology associated with the timing of pubertal development? Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 36, 1768–1776. doi:10.1097/00004583-199712000-00026.

Graber, J. A., Petersen, A. C., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (1996). Pubertal processes: Methods, Measures, and Methods. In J. A. Graber, J. Brooks-Gunn, & A. C. Petersen (Eds.), Transitions through adolescence (pp. 23–53). Mahwah, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Graber, J. A., Seeley, J. R., Brooks-Gunn J., & Lewinsohn, P. M. (2004). Is pubertal timing associated with psychopathology in young adulthood? Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 43, 718–726. doi:10.1097/01.chi.0000120022.14101.11.

Grover, R. L., Nangle, D. W., & Zeff, K. R. (2005). The measure of adolescent heterosocial competence: development and initial construct validation. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 34, 282–291. doi:10.1207/s15374424jccp3402_7.

Hammen, C. (1991). Generation of stress in the course of unipolar depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100, 555–561. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.100.4.555.

Hankin, B. L., & Abramson, L. Y. (2001). Development of gender differences in depression: An elaborated cognitive vulnerability-transactional stress theory. Psychological Bulletin, 127, 773–796. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.127.6.773.

Hayward, C., & Sanborn, K. (2002). Puberty and the emergence of gender differences in psychopathology. Journal of Adolescent Health, 30S, 49–58. doi:10.1016/S1054-139X(02)00336-1.

Huddleston, J., & Ge, X. (2003). Boys at puberty: Psychosocial implications. In C. Hayward (Ed.), Gender differences at puberty (pp. 113–136). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Joyner, K., & Urdy, J. R. (2000). You don’t bring me anything but down: Adolescent romance and depression. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 41, 369–391. doi:10.2307/2676292.

Kaufman, J., Birmaher, B., Brent, D., & Rao, U. (1997). Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): Initial reliability and validity data. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 36, 980–988. doi:10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021.

Larson, R. W., Clore, G. L., & Wood, G. A. (1999). The emotions of romantic relationships: Do they wreak havoc on adolescents? In W. Furman, B. B. Brown, & C. Feiring (Eds.), The development of romantic relationships during adolescence (pp. 19–49). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Michael, A., & Eccles, J. S. (2003). When coming of age means coming undone: Links between puberty and psychosocial adjustment among European American and African American girls. In C. Hayward (Ed.), Gender differences at puberty (pp. 113–136). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Moffit, T. E. (1993). Adolescence-limited and life-course persistent antisocial behavior: A development taxonomy. Psychological Review, 100, 674–701. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.100.4.674.

National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (n.d.). 2005 Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Retrieved April 14, 2008, from http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/yrbss/QuestYearTable.asp?path=byHT&ByVar=CI&cat=4&quest=Q58&year=2005&loc=XX.

Neeman, J., Hubbard, J., & Masten, A. S. (1995). The changing importance of romantic relationship involvement to competence from late childhood to late adolescence. Development and Psychopathology, 7, 727–750.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Girgus, J. S. (1994). The emergence of gender differences in depression during adolescence. Psychological Bulletin, 115, 424–443. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.115.3.424.

Petersen, A. C., & Crockett, L. (1985). Pubertal timing and grade effects on adjustment. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 14, 191–207. doi:10.1007/BF02090318.

Petersen, A. C., Crockett, L., Richards, M., & Boxer, A. (1988). A self-report measure of pubertal status: Reliability, Validity, and Initial Norms. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 17, 117–133. doi:10.1007/BF01537962.

Phinney, V. G., Jensen, L. C., Olsen, J. A., & Cundick, B. (1990). The relationship between early development and psychosexual behaviors in adolescent females. Adolescence, 25, 321–332.

Public School Review (n.d.). Retrieved February 1, 2007, from http://www.publicschoolreview.com.

Radloff, L. S. (1977). A CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401. doi:10.1177/014662167700100306.

Rende, R., Slomkowski, C., Lloyd-Richardson, E., Stroud, L., & Niaura, R. (2006). Estimating genetic and environmental influences on depressive symptoms in adolescence: Differing effects on higher and lower levels of symptoms. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 35, 237–243. doi:10.1207/s15374424jccp3502_7.

Reuter, M. A., Scaramella, L., Wallace, L. E., & Conger, R. D. (1999). First onset of depressive or anxiety disorders predicted by the longitudinal course of internalizing symptoms and parent-adolescent disagreements. Archives of General Psychiatry, 56, 726–732. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.56.8.726.

Smolak, L., Levine, M. P., & Gralen, S. (1993). The impact of puberty and dating on eating problems among middle school girls. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 22(4), 355–368. doi:10.1007/BF01537718.

Stattin, H., & Magnusson, D. (1990). Pubertal maturation in female development. In D. Magnusson (Ed.), Paths through life. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Steinberg, S. J., & Davila, J. (in press). Romantic functioning and depressive symptoms among early adolescent girls: The moderating role of parental emotional availability. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology.

Steinberg, S. J., Davila. J., & Fincham, F. D. (2006). Adolescent romantic expectations and experiences: Associations with perceptions about parental conflict and adolescent attachment security. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 35, 314–329. doi:10.1007/s10964-006-9042-9.

Welsh, D. P., Grello, C. M., & Harper, M. S. (2003). When love hurts: Depression and adolescent romantic relationships. In P. Florsheim (Ed.), Adolescent romantic relations and sexual behavior: Theory, research, and practical implications (pp. 185–212). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by NIMH R01 MH063904-1A2 and by funds from the State University of New York, Stony Brook. The authors would like to thank Melissa Ramsay Miller, Lisa R. Starr, Sara J. Steinberg and Athena Yoneda for their assistance with data collection, and the families who generously participated in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Stroud, C.B., Davila, J. Pubertal Timing and Depressive Symptoms in Early Adolescents: The Roles of Romantic Competence and Romantic Experiences. J Youth Adolescence 37, 953–966 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-008-9292-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-008-9292-9