Abstract

Objectives

Drawing from a social disorganization perspective, this research addresses the effect of immigration on crime within new destinations—places that have experienced significant recent growth in immigration over the last two decades.

Methods

Fixed effects regression analyses are run on a sample of n = 1252 places, including 194 new destinations, for the change in crime from 2000 to the 2005–2007 period. Data are drawn from the 2000 Decennial Census, 2005–2007 American Community Survey, and the Uniform Crime Reports. Places included in the sample had a minimum population of 20,000 as of the 2005-07 ACS. New destinations are defined as places where the foreign-born have increased by 150 % or more since 1990 and with a minimum foreign-born population of 1000 in 2007.

Results

Results indicate new destinations experienced greater declines in crime, relative to the rest of the sample. Moreover, new destinations with greater increases in foreign-born experienced greater declines in their rates of crime. Additional predictors of change in crime include change in socioeconomic disadvantage, the adult-child ratio, and population size.

Conclusions

Results fail to support a disorganization view of the effect of immigration on crime in new destinations and are more in line with the emerging community resource perspective. Limitations and suggestions for future directions are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For example, Card (1990) finds that the influx of Mariel Cubans into Miami had virtually no effect on the wages of Miami's existing workforce precisely because previous waves of immigrants resulted in large numbers of immigrant employers who were able to absorb the newcomers.

The ACS provides much of the same information as the Census (in most cases the wording of questions is identical), the major differences being that the ACS is conducted in 1-, 3-, and 5-year waves and is extrapolated from a sample of the population, as opposed to the counts offered by the Census. Though few studies have used the ACS to date, there are several reasons to do so. First, because it is conducted yearly, the ACS provides some of the most recent data available on demographic and economic characteristics for the nation’s population. Second, the ACS offers data products in 1-, 3-, and 5-year forms, with each increase in the number of years corresponding to a smaller population threshold for inclusion, essentially allowing researchers the option of choosing between increased data currency or heightened stability. Third, in contrast to a point-in-time survey such as the decennial census, wherein data are tied to a specific date, ACS data represent the average of any given characteristic over a 1-, 3-, or 5-year period.

Twenty-thousand is the minimum population size for places included in the ACS 3-year product.

The ACS 5-year product is generalizable to all-places in the US, with no minimum size requirement. However, as the ACS began in 2005, the first available 5-year wave is 2009.

I thank the anonymous reviewer for raising this important question, which is also discussed further in the limitations section.

In each case, a minimum of two years of reporting was required for inclusion in the analysis. Any place for which two years of data in each period could not be obtained was excluded from the analysis.

For sake of brevity, only the analyses of the three index measures of crime are presented here. Additional analyses were also run on each type of crime for each time period, for a total of 12 more models, all of which are substantively similar to the ones presented here. They are available upon request from the author.

It was hoped that this index would also include the z-score for the percent of the population that speaks English less than very well, capturing variations in human capital. However, given the extent of missing values on that measure, as drawn from the ACS 2005–2007, it was excluded to preserve sample size.

For the first time period, recent immigrants are those who arrived between January 1995 and March 2000; for the second time period, those who arrived between January 2000 and the average of 2005–2007. Because the ACS data are essentially averaged across the period and because growth in immigration began to slow from 2006 to 2007 (before leveling off from 2007 to 2008), the total number of recent foreign-born drawn from the data set most closely resembles the total from 2006, effectively adding only one additional year’s worth of immigrants.

Analyses were also run with a total-foreign-born index in place of the recent foreign-born index presented here. Results do not differ substantively and are available for interested readers upon request.

Pre-1990 immigration counts are calculated from the measure on foreign-born year-of-entry provided in both the 2000 decennial Census and the 2005–2007 ACS.

Additional analyses (not shown but available upon request) were run wherein new destinations were operationalized as (1) places whose recent foreign-born population increased by 150 % with a minimum of 500 of foreign-born in the 2005–2007 time period (n = 200). The results obtained using this alternative specification did not significantly differ from what is presented here.

Since the unit of analysis here is cities, rather than counties, it may be argued that the above operationalization undercounts new destination places. However, as few studies on new destinations and crime exist at the place-level, an approach modeled on the established literature seems warranted.

The analyses were re-run (not shown) with a disadvantage index containing the percent of the population that is non-Hispanic black, in addition to the items mentioned above, and a third time with the NH Black measure included as its own predictor, with no substantive differences to the results discussed here. The only considerable effect of the measure’s inclusion was to reduce the overall sample size by approximately 60 cases, due to missing data from the ACS.

The decision to use two years as the measure of stability is entirely data-driven, as appears to be the case for other researchers. The 2000 census specifically asks whether householders have resided in the same place for at least the last five years, while the ACS asks only whether residence has been continuous since the previous year. Such a disparity is unacceptable. Fortunately, each data set also includes a variable reporting when the householder moved into the home. As a result, the stability variable incorporated here from the ACS measures the percentage of householders who moved in prior to 2004, two years from the median time point of the data set, while the decennial census variable measures the percentage of the population who moved in prior to 1998, approximately two years prior to the decennial census.

To confirm the fit of a fixed effects model over a random effects one, I performed a centered scores test. The results suggest that the random effect is in fact correlated with the measured predictor variables, warranting the use of a fixed effects model.

An additional benefit is that, because there are only two time points, the within-unit differences for all measures are approximately normally distributed, precluding the need to modify measures and easing interpretation of results.

References

Agnew R (2001) Juvenile delinquency: causes and control. Roxbury Publishing, Los Angeles

Alaniz ML, Cartmill RS, Parker RN (1998) Immigrants and Violence: the Importance of Neighborhood Context. Hisp J Behav Sci 20:155–175

Allison PD (2005) Fixed effects regression methods for longitudinal data using SAS. SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC

Alsalam N, Smith RE (2005) The role of immigrants in the U.S. Labor Market, Congressional Budget Office, Washington, DC. http://www.cbo.gov/ftpdocs/68xx/doc6853/11-10-Immigration.pdf

Beaulieu M, Messner SF (2010) Assessing changes in the effect of divorce rates on homicide rates across large US cities, 1960–2000: revisiting the Chicago school. Homicide Stud 14:24–51

Butcher KF, Piehl AM (1998) Cross-city evidence on the relationship between immigration and crime. J Policy Anal Manage 17:457–493

Card D (1990) The impact of the Mariel boatlift on the miami labor market. Ind Labor Relat Rev 43:245–257

Chamlin MB (1989) A macro social analysis of the change in robbery and homicide rates: controlling for static and dynamic effects. Sociol Focus 22:275–286

Crowley M, Lichter DT (2009) Social disorganization in new latino destinations? Rural Sociol 74:573–604

Desmond SA, Kubrin CE (2009) The power of place: immigrant communities and adolescent violence. Sociol Q 50:581–607

Donato KM, Tolbert C, Nucci A, Kawano Y (2008) Changing faces, changing places: the emergence of new nonmetropolitan immigrant gateways. In: Massey DS (ed) New faces in new places: the changing geography of American immigration. Russell Sage, New York, pp 75–98

Feldmeyer B (2009) Immigration and violence: the offsetting effects of immigrant concentration on Latino violence. Soc Sci Res 38:717–731

Fennelly K (2008) Prejudice toward immigrants in the midwest. In: Massey DS (ed) New faces in new places: the changing geography of American immigration. Russell Sage, New York, pp 151–178

Fennelly K, Federico C (2008) Rural residence as a determinant of attitudes toward US immigration policy. Int Migr 46:151–190

Frey WH (2009) The great American migration slowdown: regional and metropolitan dimensions. Metropolitan Policy Program, Brookings Institute, Washington, DC. http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/files/rc/reports/2009/1209_migration_frey/1209_migration_frey.pdf

Griffith D (2008) New midwesterners, new southerners: immigration experiences in four rural American settings. In: Massey DS (ed) New faces in new places: the changing geography of American immigration. Russell Sage, New York, pp 179–210

Hagedorn J (2008) A world of gangs: armed young men and gangsta culture. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis

Hirschi T, Gottfredson M (1983) Age and the explanation of crime. Am J Sociol 89:552–584

Kotkin J (2000) Movers and shakers: how immigrants are reviving neighborhoods given up for dead. Reason 32(7):41–46. http://reason.com/archives/2000/12/01/movers-and-shakers

LeClere FB, Rogers RG, Peters KD (1997) Ethnicity and mortality in the United States: individual and community correlates. Soc Forces 76:169–198

Lee MR, Slack T (2008) Labor market conditions and violent crime across the metro nonmetro divide. Soc Sci Res 37:753–768

Lee MT, Martinez R Jr, Rosenfeld R (2001) Does immigration increase homicide? Negative evidence from three border cities. Sociol Q 42:559–580

Lichter DT, Parisi D, Taquino MC, Grice SM (2010) Residential segregation in new hispanic destinations: cities, suburbs, and rural communities compared. Soc Sci Res 39:215–230

Liska EE, Logan JR, Bellair PE (1998) Race and violent crime in the suburbs. Am Sociol Rev 63:27–38

Logan JR, Alba RD, Zhang W (2002) Immigrant enclaves and ethnic communities in New York and Los Angeles. Am Sociol Rev 67:299–322

MacDonald J, Hipp J, Gill C (2013) The effects of immigrant concentration on changes in neighborhood crime rates. J Quant Criminol 29:191–215

Martinez R Jr (2002) Latino homicide: immigration, violence, and community. Routledge, New York

Martinez R Jr, Nielsen AL (2006) Extending ethnicity and violence research in a Multiethnic city: Haitian, African American, and Latino Nonlethal Violence. In: Peterson RD, Krivo LJ, Hagan J (eds) The many colors of crime: inequalities of race, ethnicity and crime in America. NYU Press, New York, pp 108–121

Martinez R Jr, Stowell JI (2012) Extending immigration and crime studies: national implications and local settings. Ann Am Acad Polit Soc Sci 64:174–192

Martinez R Jr, Rosenfeld R, Mares D (2008) Social disorganization, drug market activity, and neighborhood violent crime. Urban Aff Rev 43:846–847

Martinez R Jr, Stowell JI, Lee MT (2010) Immigration and crime in an Era of transformation: a longitudinal analysis of homicides in San Diego neighborhoods, 1980–2000. Criminology 48:797–829

Massey DS, Capoferro C (2008) The geographic diversification of American immigration. In: Massey DS (ed) New faces in new places: the changing geography of American immigration. Russell Sage, New York, pp 25–50

Miethe TD, Hughes M, McDowall D (1991) Social change and crime rates: an evaluation of alternative theoretical approaches. Soc Forces 70:165–187

Morenoff JD, Astor A (2006) Immigrant assimilation and crime: generational differences in youth violence in Chicago. In: Martinez R Jr, Valenzuela A (eds) Immigration and crime: race, ethnicity, and violence. NYU Press, New York, pp 36–63

Morenoff JD, Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW (2001) Neighborhood inequality, collective efficacy, and the spatial dynamics of urban violence. Criminology 39:517–559

Mosher C (2001) Predicting drug arrest rates: conflict and social disorganization perspectives. Crime Delinq 47:84–104

Nielsen AL, Martinez R Jr (2006) Multiple disadvantages and crime among black immigrants: exploring Haitian violence in Miami’s communities. In: Martinez R Jr, Valenzuela A (eds) Immigration and crime: race, ethnicity, and violence. NYU Press, New York, pp 212–233

Oberle A, Li W (2008) Diverging trajectories: Asian and Latino immigration in metropolitan phoenix. In: Singer A, Hardwick SW, Brettell CB (eds) Twenty-first century gateways: immigrant incorporation in suburban America. Brookings Institution Press, Washington, DC, pp 87–104

Odem ME (2008) Unsettled in the suburbs: latino immigration and ethnic diversity in Metro Atlanta. In: Singer A, Hardwick SW, Brettell CB (eds) Twenty-first century gateways: immigrant incorporation in Suburban America. Brookings Institution Press, Washington, DC, pp 105–136

Ousey GC, Kubrin CE (2009) Exploring the connection between immigration and violent crime rates in US cities, 1980–2000. Soc Probl 56:447–473

Ousey GC, Lee MR (2007) Homicide trends and illicit drug markets: exploring differences across time. Justice Q 24:48–79

Parrado EA, Kandel W (2008) New hispanic migrant destinations: a tale of two industries. In: Massey DS (ed) New faces in new places: the changing geography of American immigration. Russell Sage, New York, pp 99–123

Peterson RD, Krivo LJ (1993) Racial segregation and black urban homicide. Soc Forces 71:1001–1026

Portes A, Jensen L (1992) Disproving the enclave hypothesis. Am Sociol Rev 57:418–420

Portes A, Rumbaut R (2006) Immigrant America: a portrait. University of California Press, Los Angeles

Portes A, Zhou M (1993) The new second generation: segmented assimilation and its variants. Ann Am Acad Polit Soc Sci 530:74–96

Price M, Singer A (2008) Edge gateways: immigrants, suburbs, and the politics of reception in metropolitan Washington. In: Singer A, Hardwick SW, Brettell CB (eds) Twenty-first century gateways: immigrant incorporation in Suburban America. Brookings Institution Press, Washington, DC, pp 137–170

Reid LW, Weiss H, Adelman RM, Jaret C (2005) The immigration-crime relationship: evidence across US metropolitan areas. Soc Sci Res 34:757–780

Sampson RJ (1985) Structural sources of variation in race-age-specific rates of offending across major US cities. Criminology 23:647–673

Sampson RJ (1986) Crime in cities: the effects of formal and informal social control. Crime Justice 8:271–311

Sampson RJ (1987) Urban black violence: the effect of male joblessness and family disruption. Am J Sociol 93:348–382

Sampson RJ, Bean L (2006) Cultural mechanisms and killing fields: a revised theory of community-level inequality. In: Krivo LJ, Peterson RD, Hagan J (eds) The many colors of crime: inequalities of race, ethnicity and crime in America. New York University Press, New York, pp 8–36

Sampson RJ, Laub JH (1993) Crime in the making: pathways and turning points through life. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

Sampson RJ, Morenoff JD, Earls F (1999) Beyond social capital: spatial dynamics of collective efficacy for children. Am Sociol Rev 64:633–660

Sampson RJ, Morenoff JD, Raudenbush S (2005) Social anatomy of racial and ethnic disparities in violence. Public Health Matters 95:224–232

Schulenberg JL (2003) The social context of police discretion with young offenders: an ecological analysis. Can J Criminol Crim Justice 45:127–157

Shaw CR, McKay HD (1942) Juvenile delinquency in urban areas. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Shihadeh ES, Barranco RE (2010) Leveraging the power of the ethnic enclave: residential instability and violence in Latino communities. Sociol Spectr 30:249–269

Shihadeh ES, Barranco RE (2013) The imperative of place: homicide and the new Latino migration. Sociol Q 54:81–104

Shihadeh ES, Winters L (2010) Church, place, and crime: Latinos and homicides in new destinations. Sociol Inq 80:628–649

Singer A (2008) Twenty-first-century gateways: an introduction. In: Singer A, Hardwick SW, Brettell CB (eds) Twenty-first century gateways: immigrant incorporation in suburban America. Brookings Institution Press, Washington, DC, pp 3–30

Smith HA, Furseth OJ (2008) The ‘Nuevo South’: Latino place making and community building in the middle-ring suburbs of charlotte. In: Singer A, Hardwick SW, Brettell CB (eds) Twenty-first century gateways: immigrant incorporation in Suburban America. Brookings Institution Press, Washington, DC, pp 281–307

Steffensmeier D, Haynie DL (2000) The structural sources of urban female violence in the United States. Homicide Stud 4:107–134

Stowell JI, Messner SF, McGeever KF, Raffalovich LE (2009) Immigration and the recent violent crime drop in the United States: a pooled, cross-sectional time-series analysis of metropolitan areas. Criminology 47:889–928

US Census Bureau (2009) American community survey. http://www.census.gov/acs/www/

Velez MB, Krivo LJ, Peterson RD (2003) Structural inequality and homicide: an assessment of the black-white gap in killings. Criminology 41:645–672

Wadsworth T (2010) Is immigration responsible for the crime drop? An assessment of the influence of immigration on changes in violent crime between 1990 and 2000. Soc Sci Q 91:531–553

Weijters G, Scheepers P, Gerris J (2007) Distinguishing the city, neighborhood, and individual level in the explanation of youth delinquency: a multilevel approach. Eur J Criminol 4:87–108

Weijters G, Scheepers P, Gerris J (2009) City and/or neighbourhood determinants? Studying contextual effects on youth delinquency. Eur J Criminol 6:439–455

Winders J (2008) Nashville’s new ‘Sonido’: Latino migration and the changing politics of race. In: Massey DS (ed) New faces in new places: the changing geography of American immigration. Russell Sage, New York, pp 249–273

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their detailed and constructive comments, which have significantly improved the final paper. The author also wishes to thank the Editor for his helpful comments and support during the review process.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

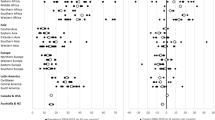

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ferraro, V. Immigration and Crime in the New Destinations, 2000–2007: A Test of the Disorganizing Effect of Migration. J Quant Criminol 32, 23–45 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-015-9252-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-015-9252-y