Abstract

In priority sub-Saharan African countries, on the ground observations suggest that the success of voluntary medical male circumcision (VMMC) programs should not be based solely on numbers of males circumcised. We identify gaps in the consent process and poor psychosocial outcomes among a key target group: male adolescents. We assessed compliance with consent and assent requirements for VMMC in western Kenya among males aged 15–19 (N = 1939). We also examined differences in quality of life, depression, and anticipated HIV stigma between uncircumcised and circumcised adolescents. A substantial proportion reported receiving VMMC services as minors without parent/guardian consent. In addition, uncircumcised males were significantly more likely than their circumcised peers to have poor quality of life and symptoms of depression. Careful monitoring of male adolescents’ well-being is needed in large-scale VMMC programs. There is also urgent need for research to identify effective strategies to address gaps in the delivery of VMMC services.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). Joint strategic action framework to accelerate the scale-up of voluntary medical male circumcision for HIV prevention in Eastern and Southern Africa. Geneva: UNAIDS/WHO; 2011.

Auvert B, Taljaard D, Lagarde E, Sobngwi-Tambekou J, Sitta R, Puren A. Randomized, controlled intervention trial of male circumcision for reduction of HIV infection risk: the ANRS 1265 Trial. PLoS Med. 2005;2(11):e298.

Bailey RC, Moses S, Parker CB, et al. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in young men in Kisumu, Kenya: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;369(9562):643–56.

Gray RH, Kigozi G, Serwadda D, et al. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in men in Rakai, Uganda: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2007;369(9562):657–66.

Government of Kenya Ministry of Health, National AIDS and STI Control Program (NASCOP). National voluntary medical male circumcision strategy, 2014/15–2018/19. 2nd ed. Nairobi: Ministry of Health, NASCOP; 2015.

World Health Organization (WHO). WHO progress brief: voluntary medical male circumcision for HIV prevention. Geneva: WHO; 2018.

World Health Organization (WHO), Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). A framework for voluntary medical male circumcision: effective hiv prevention and a gateway to improved adolescent boys’ & men’s health in Eastern and Southern Africa By 2021. Geneva: WHO; 2016.

US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). Strategy for accelerating HIV/AIDS epidemic control (2017–2020). Washington DC: US Department of State, Office of the US Global AIDS Coordinator and Health Diplomacy; 2017.

Kripke K, Njeuhmeli E, Samuelson J, et al. Assessing progress, impact, and next steps in rolling out voluntary medical male circumcision for HIV prevention in 14 priority countries in eastern and Southern Africa through 2014. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(7):e0158767.

Kripke K, Opuni M, Schnure M, et al. Age targeting of voluntary medical male circumcision programs using the Decision Makers’ Program Planning Toolkit (DMPPT) 2.0. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(7):e0156909.

Kripke K, Opuni M, Odoyo-June E, et al. Data triangulation to estimate age-specific coverage of voluntary medical male circumcision for HIV prevention in four Kenyan counties. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(12):e0209385.

Gathura, G. Exposed: mystery of Kenya’s ‘ghost circumcisions’. Standard Digital; December 29, 2018. https://www.standardmedia.co.ke/article/2001307681/exposed-mystery-of-kenya-s-ghost-circumcisions. Accessed Apr 2019.

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). AIDS Info 2018. http://aidsinfo.unaids.org/. Accessed 2018.

Government of Kenya Ministry of Health, National AIDS Control Council (NACC). Kenya AIDS response progress report. Nairobi: Ministry of Health, NACC; 2016. p. 2016.

Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS). Kenya demographic and health survey. Nairobi: KNBS; 2014. p. 2015.

Hines JZ, Ntsuape OC, Malaba K, et al. Scale-Up of voluntary medical male circumcision services for HIV prevention—12 countries in Southern and Eastern Africa, 2013–2016. MMWR. 2017;66(47):1285–90.

Byabagambi J, Marks P, Megere H, et al. Improving the quality of voluntary medical male circumcision through use of the continuous quality improvement approach: a pilot in 30 PEPFAR-supported sites in Uganda. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(7):e0133369.

Davis SM, Hines JZ, Habel M, et al. Progress in voluntary medical male circumcision for HIV prevention supported by the US President’s emergency plan for AIDS relief through 2017: longitudinal and recent cross-sectional programme data. BMJ Open. 2018;8(8):e021835.

Government of Kenya, Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation, National AIDS/STI Control Programme. Voluntary medical male circumcision for HIV prevention in Kenya: report of the first rapid results initiative. November/December 2009. Nairobi: Ministry of Public Health & Sanitation, NASCOP; 2009. p. 2010.

Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine. Advocating for adolescent and young adult male sexual and reproductive health: a position statement from the Society for adolescent health and medicine. J Adolesc Health. 2018;63(5):657–61.

Dam KH, Kaufman MR, Patel EU, et al. Parental communication, engagement, and support during the adolescent voluntary medical male circumcision experience. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66:S189–97.

Namatsi V. Trouble after school circumcises pupils without parents consent. Citizen Digital; Updated August 1, 2016. https://citizentv.co.ke/news/trouble-after-school-circumcises-pupils-without-parents-consent-135545/. Accessed 2018.

Omoro J. I want my son’s foreskin returned—Homa Bay dad. SDE, The Nairobian; Updated January 2018. https://www.sde.co.ke/thenairobian/article/2001263873/i-want-my-son-s-foreskin-returned-homa-bay-dad. Accessed 2018.

Hinkle LE, Toledo C, Grund JM, et al. Bleeding and blood disorders in clients of voluntary medical male circumcision for HIV prevention—Eastern and Southern Africa, 2015–2016. MMWR. 2018;67(11):337–9.

Govender K, George G, Beckett S, Montague C, Frohlich J. Risk compensation following medical male circumcision: results from a 1-year prospective cohort study of young school-going men in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Int J Behav Med. 2018;25(1):123–30.

Shi C-F, Li M, Dushoff J. Evidence that promotion of male circumcision did not lead to sexual risk compensation in prioritized Sub-Saharan countries. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(4):e0175928.

George G, Strauss M, Chirawu P, et al. Barriers and facilitators to the uptake of voluntary medical male circumcision (VMMC) among adolescent boys in KwaZulu–Natal, South Africa. AJAR. 2014;13(2):179–87.

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). Safe, voluntary, informed male circumcision and comprehensive HIV prevention programming: guidance for decision-makers on human rights, ethical and legal considerations. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2008.

Gilbertson A, Ongili B, Odongo FS, et al. Voluntary Medical Male Circumcision for HIV prevention among adolescents in Kenya: unintended consequences of pursuing service-delivery targets. Unpublished.

Skevington SM, Lotfy M, O’Connell KA. The World Health Organization’s WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment: psychometric properties and results of the international field trial. A report from the WHOQOL Group. Qual Life Res. 2004;13(2):299–310.

Skevington SM, Dehner S, Gillison FB, McGrath EJ, Lovell CR. How appropriate is the WHOQOL-BREF for assessing the quality of life of adolescents? Psychol Health. 2014;29(3):297–317.

Enimil A, Nugent N, Amoah C, et al. Quality of life among Ghanaian adolescents living with perinatally acquired HIV: a mixed methods study. AIDS Care. 2016;28(4):460–4.

Ongeri L, McCulloch CE, Neylan TC, et al. Suicidality and associated risk factors in outpatients attending a general medical facility in rural Kenya. J Affect Disord. 2018;225:413–21.

Musyimi CW, Mutiso VN, Nayak SS, Ndetei DM, Henderson DC, Bunders J. Quality of life of depressed and suicidal patients seeking services from traditional and faith healers in rural Kenya. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017;15(1):95.

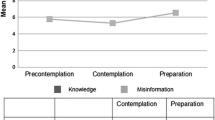

Field SH, Iritani BJ, Luseno WK. Quality of life, depressive symptoms, and anticipated HIV stigma: measuring psychosocial well-being of adolescents in a high HIV prevalence region of Kenya. Unpublished.

Van Dam NT, Earleywine M. Validation of the center for epidemiologic studies depression scale-revised (CESD-R): pragmatic depression assessment in the general population. Psychiatry Res. 2011;186(1):128–32.

Cheng Y, Li X, Lou C, et al. The association between social support and mental health among vulnerable adolescents in five cities: findings from the study of the well-being of adolescents in vulnerable environments. J Adolesc Health. 2014;55(6, Suppl):S31–8.

Nduna M, Jewkes RK, Dunkle KL, Shai NPJ, Colman I. Prevalence and factors associated with depressive symptoms among young women and men in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. J Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2013;25(1):43–54.

MacPherson P, Webb EL, Choko AT, et al. Stigmatising attitudes among people offered home-based HIV testing and counselling in Blantyre, Malawi: construction and analysis of a stigma scale. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(10):1–9.

Republic of Kenya. Laws of Kenya. Children act, No. 8 of 2001. Kenya: National Council for Law Reporting with the Authority of the Attorney-General; 2018.

Olagunju AT, Aina OF, Fadipe B. Screening for depression with Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale Revised and its implication for consultation–liaison psychiatry practice among cancer subjects: a perspective from a developing country. Psycho-Oncology. 2013;22(8):1901–6.

Montague C, Ngcobo N, Mahlase G, et al. Implementation of adolescent-friendly voluntary medical male circumcision using a school based recruitment program in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(5):e96468.

George G, Govender K, Beckett S, Montague C, Frohlich J. Factors associated with the take-up of voluntary medical male circumcision amongst learners in rural KwaZulu-Natal. AJAR. 2017;16(3):251–6.

U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). PEPFAR’s best practices for voluntary medical male circumcision site operations: a service guide for site operations. Washington, DC: United States Agency for International Development, U.S. Department of State; 2017.

Cluver L, Gardner F, Operario D. Poverty and psychological health among AIDS-orphaned children in Cape Town, South Africa. AIDS Care. 2009;21(6):732–41.

American College of Pediatricians. Parental notification/consent for treatment of the adolescent. Issues Law Med. 2015;30(1):99–105.

Kaufman MR, Patel EU, Dam KH, et al. Impact of counselling received by adolescents undergoing voluntary medical male circumcision on knowledge and sexual intentions. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66:S221–8.

Groves AK, Hallfors DD, Iritani BJ, et al. “I think the parent should be there because no one was born alone”: kenyan adolescents’ perspectives on parental involvement in HIV research. AJAR. 2018;17(3):227–39.

World Health Organization (WHO). Manual for male circumcision under local anaesthesia and HIV prevention services for adolescent boys and men. Geneva: WHO; 2018.

Center for Reproductive Rights. Capacity and consent. Empowering adolescents to exercise their reproductive rights. New York: Center for Reproductive Rights; 2017.

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported by funding from the National Institute of Mental Health and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01MH102125 (Luseno, W.K., PI). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The research used the World Health Organization Quality of Life Questionnaire (WHOQOL-BREF). We are grateful to Shane Hartman and research assistants at KEMRI for their important contributions to this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Luseno, W.K., Field, S.H., Iritani, B.J. et al. Consent Challenges and Psychosocial Distress in the Scale-up of Voluntary Medical Male Circumcision Among Adolescents in Western Kenya. AIDS Behav 23, 3460–3470 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-019-02620-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-019-02620-7