Abstract

Objective/Background: Aboriginals constitute a substantial portion of the population of Northern Alberta. Determinants such as poverty and education can compound health-care accessibility barriers experienced by Aboriginals compared to non-Aboriginals. A diabetes care enhancement study involved the collection of baseline and follow-up data on Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal patients with known type 2 diabetes in two rural communities in Northern Alberta. Analyses were conducted to determine any demographic or clinical differences existing between Aboriginals and non-Aboriginals.

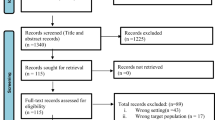

Methods: 394 diabetes patients were recruited from the Peace and Keeweetinok Lakes health regions. 354 self-reported whether or not they were Aboriginal; a total of 94 selfreported being Aboriginal. Baseline and follow-up data were collected through interviews, standardized physical assessments, laboratory testing and self-reporting questionnaires (RAND-12 and HUI3).

Results: Aboriginals were younger, with longer duration of diabetes, more likely to be female, and less likely to have completed high school. At baseline, self-reported health status was uniformly worse, but the differences disappeared with adjustments for sociodemographic confounders, except for perceived mental health status. Aboriginals considered their mental health status to be worse than non-Aboriginals at baseline. Some aspects of health utilization were also different.

Discussion: While demographics were different and some utilization differences existed, overall this analysis demonstrates that “Aboriginality” does not contribute to diabetes outcomes when adjusted for appropriate variables.

Résumé

Objectif et contexte: Les Autochtones représentent une part substantielle de la population du Nord de l’Alberta. Les déterminants comme la pauvreté et l’instruction peuvent aggraver les problèmes d’accès aux soins de santé que vivent les Autochtones par rapport au reste de la population. Dans le cadre d’une étude sur l’amélioration des soins du diabète, nous avons recueilli des données de référence et de suivi auprès de patients autochtones et non autochtones ayant reçu un diagnostic de diabète de type II dans deux communautés rurales du Nord de l’Alberta. Nous avons ensuite effectué des analyses pour déterminer l’existence de différences démographiques ou cliniques entre les Autochtones et les non-Autochtones.

Méthode: Nous avons recruté 394 patients diabétiques dans les régions sanitaires de Peace et de Keeweetinok Lakes. De ces patients, 354 ont indiqué s’ils étaient autochtones ou non; 94 ont dit l’être. Nous avons recueilli les données de référence et de suivi au moyen d’entretiens, d’examens médicaux standardisés, d’épreuves de laboratoire et de questionnaires d’auto-évaluation (le RAND- 12 et le HUI3).

Résultats: Les Autochtones étaient plus jeunes, ils étaient diabétiques depuis plus longtemps, ils comptaient proportionnellement plus de femmes dans leurs rangs, et ils étaient moins susceptibles d’avoir terminé leurs études secondaires. Dans les données de référence, leur état de santé autoperçu était uniformément pire que celui des non-Autochtones, mais ces écarts disparaissent après ajustement selon les facteurs confusionnels sociodémographiques, sauf pour l’état de santé mentale autoperçu. Les Autochtones considéraient leur état de santé mentale pire que celui des non-Autochtones dans les données de référence. Nous avons aussi observé des écarts dans certains aspects de leur utilisation des services de santé.

Discussion: Malgré un profil démographique différent et quelques écarts au chapitre de l’utilisation des services de santé, dans l’ensemble, notre analyse démontre que le fait d’être autochtone ne contribue pas aux résultats du diabète lorsqu’on apporte des ajustements selon les variables pertinentes.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Glasgow RE, Strycker LA. Preventive care practices for diabetes management in two primary care samples. Am J Prev Med 2000;19(1):9–14.

Hiss RG, Anderson RM, Hess GE, Stepien CJ, David WK. Community diabetes care: A 10-year perspective. Diabetes Care 1994;17(10):1124–34.

Streja DA, Rabkin SW. Factors associated with implementation of preventive care measures in patients with diabetes mellitus. Arch Intern Med 1999;159(3):294–302.

Tonelli M, Hemmelgarn B, Manns B, Pylypchuk G, Bohm C, Yeates K, et al. Death and renal transplantation among Aboriginal people undergoing dialysis. CMAJ 2004;171(6):577–82.

Toth EL, Majumdar SM, Lewanczuk RZ, Lee TK, Johnson JA. Compliance with clinical practice guidelines for type 2 diabetes in rural patients: Treatment gaps and opportunities for improvement. Pharmacotherapy 2003;23(5):659–65.

Wandell P, Borsson B, Aber H. Diabetic patients in primary health care: Quality of care three years apart. Scand J Prim Health Care 1998;16:44–49.

Supina AL, Guirguis LM, Majumdar SR, Lewanczuk RZ, Lee TK, Toth EL, Johnson JA. Treatment gaps for hypertension management in rural Canadian patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Clin Therapeut 2004;26:598–606.

Majumdar SR, Johnson JA, Guirguis LM, Lewanczuk RZ, Lee TK, Toth EL. A prospective controlled trial of an intervention to improve care for patients with diabetes in rural communities: Rationale and design for the DOVE study. Can J Diabetes 2001;25:173–79.

Alberta Health and Wellness - Health Surveillance Branch. Health Trends in Alberta - Chronic Disease and Injury (Section D). D-25-D-26. 2001. Alberta Health and Wellness.

Alberta Health and Wellness. Alberta Diabetes Strategy 2003–2013. 2003;3. Available online at: http://www.health.gov.ab.ca/public/dis_diabetesstrategy.pdf (Accessed March 10, 2005).

Lillie-Blanton M, Laveist T. Race/ethnicity, the social environment, and health. Soc Sci Med 1996;43(1):83–91.

Rogers R. Living and dying in the U.S.A.: Sociodemographic determinants of death among blacks and whites. Demography 1992;29(2):287.

Cass A. Health outcomes in Aboriginal populations. CMAJ 2004;171(6):597–98.

Maddigan SL, Majumdar SR, Guirguis LM, Lewanczuk RZ, Lee TK, Toth EL, Johnson JA. Improvements in patient-reported outcomes associated with an intervention to enhance quality of care for rural patients with type 2 diabetes. Results of a controlled trial. Diabetes Care 2004;27(6):1306–12.

Majumdar SR, Guirguis LM, Toth EL, Lewanczuk RZ, Lee TK, Johnson JA. Controlled trial of a multifaceted intervention for improving quality of care for rural patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2003;26:3061–66.

Alberta Health and Wellness - Health Surveillance Branch. Population projections for Alberta and its Health Regions 2000–2030. Alberta Health and Wellness, 2001;13.

Statistics Canada. Health Indicators 82-221-XIE. 2003(2).

Hays RD. RAND-36 Health Status Inventory. San Antonio, The Psychological Corporation, 1998.

Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull 1992;112:155–59.

Feeny D, Furlong W, Torrance GW, Goldsmith CH, Zhu Z, DePauw S, et al. Health Utilities Index. Multiattribute and single-attribute utility functions for the Health Utilities Index Mark 3 system. Med Care 2002;40(2):113–28.

Grootendorst P, Feeny D, Furlong W. Health Utilities Index Mark 3: Evidence of construct validity for stroke and arthritis in a population health survey. Med Care 2000;38(3):290–99.

Horsman JR, Furlong W, Feeny D, Torrance GW. The Health Utilities Index (HUI): Concepts, measurement properties and applications. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 2003;1:54.

Meltzer S, Leiter L, Daneman D, Gerstein HC, Lau D, Ludwig S, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of diabetes in Canada. CMAJ 1998;159:S1–S29.

Knowler WC, Pettitt DJ, Saad MF, Bennett PH. Diabetes mellitus in Pima Indians: Incidence, risk factors and pathogenesis. Diabetes and Metabolism Rev 1990;6:1–27.

Delisle HF, Rovard M, Ekoe JM. Prevalence estimates of diabetes and of other cardiovascular risk factors in the two largest Algonquin communities in Quebec. Diabetes Care 1995;18:1255–59.

Harris SB, Perkins BA, Whalen-Brough E. Noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus among First Nations children. New entity among First Nations people of north western Ontario. Can Fam Phys 1996;42:869–76.

Pioro M, Dyck RF, Gillis DC. Diabetes prevalence rates among First Nations adults on Saskatchewan reserves in 1990: Comparison by Tribal grouping, geography and with non-First Nation people. Can J Public Health 1996;87:325–28.

Dean HJ, Mundy RL, Moffatt M. Non-insulindependent diabetes mellitus in Indian children in Manitoba. CMAJ 1992;147(1):52–57.

Dean HJ, Young TK, Flett B, Wood-Steiman P. Screening for type-2 diabetes in aboriginal children in northern Canada. Lancet 1998;352:523–24.

Young TK, Reading J, Elias B, O’Neil JD. Type 2 diabetes mellitus in Canada’s First Nations: Status of an epidemic in progress. CMAJ 2000;163(5):561–66.

Cardinal JC, Schopflocher DP, Svenson LW, Morrison KB, Laing L. First Nations in Alberta: A focus on health service use. Edmonton, Alberta Health and Wellness, 2004.

Anand SS, Yusuf S, Jacobs R, Davis AD, Yi Q, Gerstein H, et al. Risk factors, atherosclerosis, and cardiovascular disease among Aboriginal people in Canada: The Study of Health Assessment and Risk Evaluation in Aboriginal Peoples (SHARE-AP). Lancet 2001;358(9288):1147–53.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

for the DOVE Investigators

Sources of funding: Financial support was provided by the Institute of Health Economics and the Canadian Diabetes Association. La traduction du résumé se trouve à la fin de l’article.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ralph-Campbell, K., Pohar, S.L., Guirguis, L.M. et al. Aboriginal Participation in the DOVE study. Can J Public Health 97, 305–309 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03405609

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03405609