Abstract

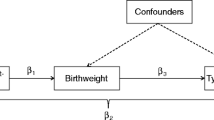

Background: Intrauterine factors have been implicated in the pathogenesis of Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).

Methods: In a 1:1 matched pairs case-control study, high and low birthweight (HBW, LBW) rates in Saskatchewan Registered Indian (RI) diabetic cases were compared with corresponding rates in RI without diabetes, and non-RI people with and without diabetes.

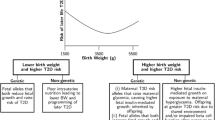

Results: Birthweights were available for 73% of the 1,366 cases and 3 × 1,366 controls. A greater proportion of RI diabetics were born with HBW (>4000 grams) compared to RI non-diabetics (16.2% vs 10.7%; p<0.01). There was a significant association between HBW (but not LBW [<2500 grams]) and diabetes for RI people (OR 1.63 [95% CI 1.20, 2.24]), which was stronger for RI females and strengthened progressively from mid to late 20th century.

Interpretation: Certain causes of HBW may predispose to subsequent development of T2DM in Canadian Aboriginal people (“hefty fetal phenotype” [“hefty fetal type”] hypothesis). Programs that optimize healthy pregnancies could reduce T2DM incidence in future generations.

Résumé

Contexte: Des facteurs intra-utérins ont été associés à la pathogénie du diabète sucré de type II (DST2).

Méthode: Dans une étude cas-témoin en paires appariées (1:1), nous avons comparé les taux d’insuffisance de poids à la naissance élevés et faibles (IPNÉ, IPNF) dans les cas de diabète chez les Indiens inscrits (Ii) de la Saskatchewan aux taux correspondants chez les Ii non diabétiques et chez les personnes non diabétiques n’étant pas des Ii.

Résultats: Nous avons obtenu le poids à la naissance de 73 % des 1 366 cas et de 3 × 1 366 témoins. La proportion d’Ii diabétiques nés avec une IPNÉ (>4 000 g) était supérieure à celle des Ii non diabétiques (16,2 % c. 10,7 %; p<0,01). L’association entre l’IPNÉ (mais non l’IPNF [<2 500 g]) et le diabète était significative chez les Ii (RC 1,63 [95 % IC 1,20, 2,24]) et plus prononcée chez les femmes; la tendance s’est renforcée progressivement entre le milieu et la fin du 20e siècle.

Interprétation: Certaines causes d’IPNÉ prédisposent peut-être au développement ultérieur du DST2 chez les Autochtones canadiens (hypothèse du «(phéno)type fœtal prononcé»). Les programmes d’optimisation de la santé durant la grossesse pourraient réduire l’incidence de DST2 pour les générations futures.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

West KM. Diabetes in North American Indians and other native populations of the New World. Diabetes 1974;23(10):841–55.

Knowler WC, Pettitt DJ, Saad MF, Bennett PH. Diabetes mellitus in the Pima Indians: Incidence, risk factors and pathogenesis. Diabetes Metab Rev 1990;6:1–27.

Young TK, Reading J, Elias B, O’Neil JD. Type 2 diabetes mellitus in Canada’s First Nations: Status of an epidemic in progress. Can Med Assoc J 2000;163(5):561–66.

Pioro MP, Dyck RF, Gillis DC. Diabetes prevalence rates among First Nations adults on Saskatchewan reserves in 1990: Comparison by tribal grouping, geography and with non-First Nations people. Can J Public Health 1996;87(5):325–28.

Dyck RF, Tan LK. Rates and outcomes of diabetic end stage renal failure among registered native people in Saskatchewan. CMAJ 1994;150:203–8.

Pettitt DJ, Bennett PH, Saad MF, et al. Abnormal glucose tolerance during pregnancy in Pima Indian women: Long-term effects on offspring. Diabetes 1991;40 Suppl 2:126–30.

Pettitt DJ, Kirk A, Aleck KA, et al. Congenital susceptibility to NIDDM: Role of the intrauterine environment. Diabetes 1988;37:622–28.

Pettitt DJ, Nelson RG, Saad MF, et al. Diabetes and obesity in the offspring of Pima Indian women with diabetes during pregnancy. Diabetes Care 1993;6(1):310–14.

King H. Epidemiology of glucose intolerance and gestational diabetes in women of childbearing age. Diabetes Care 1998;21(Suppl 2):B9–B13.

Harris SB, Caulfield LE, Sugamori ME, et al. The epidemiology of diabetes in pregnant native Canadians. Diabetes Care 1997;20(9):1422–25.

Rodrigues S, Robinson E, Gray-Donald K. Prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus among James Bay Cree women in Northern Quebec. CMAJ 1999;160:1293–97.

Godwin M, Muirhead M, Huynh J, et al. Prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus among Swampy Cree women in Moose Factory, James Bay. CMAJ 1999;160:1299–302.

Dyck RF, Tan L, Hoeppner VL. Brief communication: Relationship of body mass index and self-reported rates of gestational diabetes and diabetes mellitus with geographic accessibility — a comparison of three northern saskatchewan aboriginal communities. Chron Dis Can 1995;16(1):24–26.

Hales CN, Barker DJ, Clark PM, et al. Fetal and infant growth and impaired glucose tolerance at age 64 [see comments]. BMJ 1991;303(6809):1019–22.

Fall CH, Osmond C, Barker DJ, et al. Fetal and infant growth and cardiovascular risk factors in women. BMJ 1994;310:428–32.

Phipps K, Barker DJ, Hales CN, et al. Fetal growth and impaired glucose tolerance in men and women [see comments]. Diabetologia 1993;36(3):225–28.

Phillips DI, Barker DJ, Hales CN, et al. Thinness at birth and insulin resistance in adult life. Diabetologia 1994;37:150–54.

Barker DJ, Hales CN, Fall CH, et al. Type 2 (non insulin dependent) diabetes mellitus, hypertension and hyperlipidaemia (syndrome X): Relation to reduced fetal growth. Diabetologia 1993;36(1):62–67.

Valdez R, Athens MA, Thompson GH, et al. Birthweight and adult health outcomes in a biethnic population in the USA. Diabetologia 1994;37(6):624–31.

Lithell HO, McKeigue PM, Berglund L, et al. Relation of size at birth to non insulin dependent diabetes and insulin concentrations in men aged 50–60 years. BMJ 1996;312(7028):406–10.

Curhan GC, Willett WC, Rimm EB, et al. Birth weight and adult hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and obesity in US men. Circulation 1996;94(12):3246–50.

McCance DR, Pettitt DJ, Hanson RL, et al. Birth weight and non insulin dependent diabetes: Thrifty genotype, thrifty phenotype, or surviving small baby genotype? BMJ 1994;308(6934):942–45.

Hales CN, Barker DJ. Type 2 (non-insulin-dependent)diabetes mellitus: The thrifty phenotype hypothesis. Diabetologia 1992;35:595–601.

Edouard L, Gillis D, Habbick B. Pregnancy outcome among native Indians in Saskatchewan. CMAJ 1991;144(12):1623–25.

Tan LK, Irvine J, Habbick B, Wong A. Vital statistics in northern Saskatchewan, 1974–1988. Saskatoon: Northern Medical Services, Department of Family Medicine, University of Saskatchewan, 1992.

Tallarigo L, Giampietro O, Penno G, et al. Relation of glucose tolerance to complications of pregnancy in non-diabetic women. N Engl J Med 1986;315:989–92.

Hod M, Merlob P, Friedman S, et al. Gestational diabetes mellitus. A survey of perinatal complications in the 1980s. Diabetes 1991;40 Suppl 2:74–78.

Sermer M, Naylor C, Gare DJ, et al. Impact of increasing carbohydrate intolerance on maternal-fetal outcomes in 3637 women without gestational diabetes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1995;173:146–56.

Sermer M, Naylor C, Farine D, et al. The Toronto tri-hospital gestational diabetes project. Diabetes Care 1998;21(Suppl 2):B33–B42.

Kleinbaum DG. Maximum likelihood techniques: An overview. In: Kleinbaum DG & series editors Dietz K, Gail M, Krickeberg K, Singer B, Logistic Regression: A Self-learning Text. New York: Springer Verlag, 1994;101–24.

Kaufmann RC, Amankwah KS, Colliver JA, Arbuthnot J. Diabetic pregnancy. The effect of genetic susceptibility for diabetes on fetal weight. Am J Perinatol 1987;4(1):72–74.

Spellacy WN, Miller S, Winegar A, Peterson PQ. Macrosomia — maternal characteristics and infant complications Obstet Gynecol 1985;66:158–61.

Brunskill AJ, Rossing MA, Connell FA, Daling J. Antecedents of macrosomia. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 1991;5(4):392–401.

Moore PE, Kruse HD, Tisdall FF, Corrigan RS. Medical survey of nutrition among the northern Manitoba Indian. CMAJ 1946;54:223–33.

Vivian RP, McMillan C, Moore PE. The nutrition and health of the James Bay Indian. CMAJ 1948;59:505–19.

Knowler WC, Bennett PH, Hazzo GF, Doniach D. Islet cell antibodies and diabetes mellitus in Pima Indians. Diabetologia 1979;17:161–64.

Dean H, Mundy RL, Moffatt M. Non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in Indian children in Manitoba. CMAJ 1992;147:52–57.

Neel JV. Diabetes mellitus: A “thrifty genotype” rendered detrimental by “progress”? Am J Hum Genet 1962;14:353–62.

Moore TR. Diabetes in pregnancy. In: Creasy RK, Resnik RR, Maternal Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice, 3rd Ed. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1994;934–78.

Kuhl C. Aetiology of gestational diabetes. Baillieres Clin Obstet Gynaecol 1991;5:279–92.

Pederson J. Weight and length at birth of infants of diabetic mothers. Acta Endocrinol 1954;16:330–42.

Freinkel N. Of pregnancy and progeny. Diabetes 1980;29:1023–35.

Engelgau MM, Herman WH, Smith PJ, et al. The epidemiology of diabetes and pregnancy in the U.S., 1988. Diabetes Care 1995;18(7):1029–33.

Gabbe SG. Gestational diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 1986;315(16):1025–26.

Dyck RF, Tan LK. Differences in high birthweight rates between northern and southern Saskatchewan: implications for Aboriginal peoples. Chron Dis Can 1995;16(3):107–10.

National Database on Breastfeeding Among Indian and Inuit Women. Survey of Infant Feeding Practices from Birth to Six Months — Canada, 1983. Health and Welfare Canada, Medical Services Branch, Ottawa, 1985.

Knowler WC, Bennett PH, Hamman RF, Miller M. Diabetes incidence and prevalence in Pima Indians: A 19 fold greater incidence than in Rochester, Minn. Am J Epidemiol 1978;108:497–504.

Knowler WC, Saad MF, Pettitt DJ, et al. Determinants of diabetes mellitus in the Pima Indians. Diabetes Care 1993;16(1):216–27.

Dean H, Moffatt ME. Prevalence of diabetes melli-tus among Indian children in Manitoba. Arctic Med Res 1988;47 Suppl 1:532–34.

Dyck RF, Sheppard MS, Klomp H, et al. Using exercise to prevent gestational diabetes among Aboriginal women — hypothesis and results of a pilot/feasibility project in Saskatchewan. Can J Diabetes Care 1999;23(3):32–38.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This research was supported by a grant from the Health Services Utilization and Research Commission (HSURC) of Saskatchewan.

This study is based in part on data provided by the Saskatchewan Department of Health. The interpretations and conclusions contained herein do not necessarily represent those of the Government of Saskatchewan or the Saskatchewan Department of Health.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dyck, R.F., Klomp, H. & Tan, L. From “Thrifty Genotype” to “Hefty Fetal Phenotype”: The Relationship Between High Birthweight and Diabetes in Saskatchewan Registered Indians. Can J Public Health 92, 340–344 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03404975

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03404975