Abstract

Globally, the COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted the delivery of essential health services in general and reproductive, maternal, newborn, child health, and nutrition (RMNCHN) services in particular. The degree of disruption, however, varies disproportionately. It is more in low- and middle-income countries than in high-income countries. Focusing on India, the authors draw on various demand and supply side factors that hampered the provision of RMNCHN services and thus adversely affected many families across the country. Coupled with the gendered aspects of the social determinants of health, the pandemic intensified social vulnerabilities by impacting pregnant and lactating women and children the most. Modelling studies suggest that the progress India made over a decade on various maternal and child health and nutrition indicators may go in vain unless focused efforts are made to address the slide. Complementing government efforts to mitigate the health risks of the pandemic by strengthening health services, women-led initiatives played an important role in portraying how women’s collectives and women in leadership can be like a bridge over troubled waters in the times of a pandemic.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) affected the warp and weft of the social fabric globally. The pandemic impacted mortality and morbidity in countries around the world. There is evidence to show that more men were infected with COVID-19 as compared to women. And a higher proportion of hospitalizations, intensive care unit admissions, and deaths occurred among men [1]. The ‘tyranny of the urgent’ placed immediate biomedical needs over existing social inequities [2]. The indirect impacts of COVID-19 had gendered effects that reverberated across sectors. Women faced the social and economic consequences of the pandemic. The virus disproportionately increased the burden of unpaid care on women. It is estimated that in the formal sector, job loss rates were twice as high among women as compared to men with a high proportion of women experiencing a loss in their earnings within the first month of the pandemic. They faced serious socio-economic consequences [3, 4]. Coupled with the gendered aspects of the social determinants of health, the pandemic intensified social inequities in low- and middle-income countries. Learnings from the Ebola outbreak urge us to go beyond the binary of biomedical and social aspects and to respond with a holistic approach to reach underserved and vulnerable populations. To mobilize this response, an intersectionality approach to the pandemic is a pre-requisite [2, 5]. This is likely to enhance our understanding of systemic inequities, role of social determinants of health, and lived experiences in the context of the pandemic.

The chapter begins with a snapshot of the global and local (Indian) context of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health, and nutrition (RMNCHN). Using secondary data, we present the status of key maternal and child health indicators in the two decades prior to COVID-19 and discuss how various factors during the pandemic disrupted RMNCHN service provision adversely affecting many families across the country. We highlight the way community health workers supported the health system’s effort. We also illustrate the gendered impact of the pandemic and how it had severe negative social and economic consequences for women. We showcase the critical role that women’s groups and their federations played in underserved and marginalized communities to supplement government efforts to mitigate the health risks of the pandemic. We present these efforts through Relief, Resilience, and Recovery which we term as the ‘3R response’. We conclude by highlighting the potential of the ‘3R response’ which can serve as a model for other crisis situations in amplifying the reach of health information and services to vulnerable populations.

COVID-19 and Maternal, Newborn, and Child Health

Global Context

The COVID-19 pandemic adversely affected human life in many ways worldwide. The economic and social disruptions caused by the pandemic were devastating. Tens of millions of people were at risk of falling into extreme poverty. It is estimated that the number of undernourished people, currently about 690 million, could increase by an additional 132 million by the end of the year [6]. The pandemic challenged the resilience of health systems globally. It emerged as a threat to global public health, forcing countries to adopt several different strategies including lockdowns [7].

The health sector was affected in particular—from the provision of services to access and the utilization of health services. COVID-19 posed severe challenges for implementing much needed essential health services. It disrupted the delivery of essential health services in general and MNCH services in particular which compelled healthcare systems to prioritize services provided [8]. Healthcare workers had to cope with the rising number of COVID-19 patients. The degree of disruption, however, varied disproportionately. It was more in the low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) than in the high-income countries. The World Health Organization undertook a ‘pulse survey on the continuity of essential health services during the COVID-19 pandemic’ to estimate its impact on the delivery of essential health services across the life course [9]. In almost every country 90% of country respondents experienced some degree of service disruption with LMICs experiencing a greater extent of service disruption compared to high-income countries.

The potential effects of the virus on mothers, newborns, and pregnancy outcomes were of significant concern [10]. Research showed that nationwide lockdowns disrupted health services in many countries. And the fear of accessing health facilities affected the wellbeing of pregnant women and their babies [4, 11, 12]. Studies which modelled the indirect effects of COVID-19 on maternal and child mortality in LMICs highlighted the consequences of disruption on routine healthcare. A recent meta-analysis shows an increase in maternal mortality, stillbirths, ruptured ectopic pregnancies, pre-term births, and maternal depression during the pandemic which had disproportionate adverse effects in low resource settings [4, 13,14,15]. A reduction in seeking healthcare as well as reduced provision of maternity services were noted as possible causes [16]. Pregnant women in rural, low resource, and conflict affected settings were at greater risk because they already had inadequate access to quality care [17, 18]. Limitations in the availability of skilled health workers and challenges to using the health system led to lower coverage of ante-natal care (ANC), post-natal care (PNC), and facility and community-based lactation support and counseling for women [19].

A systematic review and meta-analysis published in the Lancet Global Health indicates that the rates of stillbirths and maternal deaths rose by about a third during the COVID-19 pandemic with outcomes showing considerable disparity in stillbirths between high and low resource settings [15]. The review also acknowledged that unequal digital access in LMICs made remote consultations less feasible leading to disruptions in preventive ante-natal care for vulnerable groups. Increase in domestic violence during the pandemic was assumed to be a contributing factor that increased maternal mortality.

The Lancet series of papers highlight the concern on maternal and child nutrition. It was noted that despite some progress, maternal and child undernutrition were a major global health concern as improvements since 2000 may have been countered by the COVID-19 pandemic [20]. The pandemic indirectly threatened breastfeeding practices such as timely initiation, exclusive, and continuous breastfeeding. Reduction in breastfeeding practices during the pandemic were due to limitation in the provision of information and advice and disruptions to the enabling environment [14]. Overall, economic, food, and health system disruptions resulting from the pandemic are expected to exacerbate all forms of malnutrition [21]. Estimates by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) suggest that because of the pandemic an additional 140 million people will be thrown into extreme poverty (less than USD 1·90 per day) by 2020 [22].

The Indian Context

The reproductive, maternal, newborn, child, and adolescent health (RMNCH + A) program is at the core of the country’s flagship program, the National Health Mission (NHM). Following a call to action summit in 2013, the Government of India took an important step to fulfil its commitment to improve maternal health and child survival through the articulation of a comprehensive approach linking together a set of initiatives and strategies that address each life stage [23]. This was a milestone in the country’s health planning for improving the availability of and access to quality healthcare, especially for people residing in rural areas, the poor, women, and children. Innovative strategies were evolved under the national program to deliver evidence-based interventions to various population groups [23]. These included selecting poor-performing districts, prioritizing high impact RMNCH + A health interventions, engaging development partners, and institutionalizing a concurrent monitoring system. This strategy helped in the development of an integrated systems based approach to address public health challenges through a comprehensive framework, defined priorities, and robust partnerships [24].

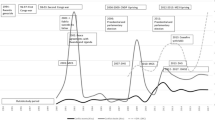

Over the past two decades, India noted significant improvements in the RMNCH indicators. Data from the National Family Health Survey showed a sharp increase in several indicators including ANC, institutional delivery, newborn care, PNC, child immunization, and child nutrition practices (Fig. 3) [25].

RMNCH services were disrupted in India after March 2020 because of the COVID-19 pandemic induced lockdown and movement restrictions. The health management information system (HMIS), which tracks indicators on the utilization of health services from over 200,000 health facilities—primary health centers to district hospitals in every district of the country and is updated nearly every day—showed that health services were severely curtailed in March 2020 as compared to previous months [26]. There were reports of supply chain disruptions due to the lockdown and associated movement restrictions resulting in medicine and vaccine stock-outs. Village health and nutrition days (VHNDs), which are the prime platforms for routine ante-natal and child immunization services, were suspended during the lockdowns. As per the HMIS data, routine check-ups of pregnant women and associated ANC tests that are important for ensuring healthy and safe pregnancy reduced during March 2020 and in the following months (Fig. 4).

Anganwadi centers stopped distributing food grains and mid-day meals services were paused as schools were stopped. Mobility restrictions also posed a severe challenge in providing post-natal care to mothers and newborns and monitoring the growth and development of children. The HMIS data indicated that there were reductions in child immunization (Fig. 5).

Multiple barriers decreased service utilization. These barriers were initial movement restrictions and decreased demand due to fear of COVID-19 infection. Several steps were taken by the government to respond to the disruptions caused by the early lockdowns. It moved to a sub-nationally driven localized containment approach that replaced widespread lockdowns with micro-pockets of restrictions determined by the states [27]. There was also greater emphasis on utilizing community health workers in multiple ways which we describe below.

Community Health Workers’ Support to the Health System’s Efforts

Community health workers or frontline health workers—accredited social health activists (ASHAs), anganwadi workers (AWWs), and auxiliary nurse midwives (ANMs)—are women cadres that constitute the healthcare workforce at the grassroots level. It serves as an interface between communities and the public health system. Two million frontline health workers have been engaged in strengthening primary healthcare outreach and community nutrition programs across the country. ASHAs, who are women residents of the village with communication skills, leadership qualities, and social capital were mobilized to engage with the community. They are the first point of contact for maternal and child health related information and services. They mobilize women for ANC services, accompany pregnant women for health facility deliveries, and play an important role in mobilizing women and children for post-natal care services including immunization. In short, ASHAs’ mandate is to generate health awareness and mobilize the community for promoting health [28].

AWWs are key personnel under the government’s flagship Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) at anganwadi centers. ICDS aims to promote child development and enhance the capabilities of mothers to look after their children’s health and nutrition. The service delivery framework of ICDS includes supplementary nutrition, immunization, health check-ups, and referral services for pregnant and lactating mothers and children below six years of age [29]. ANMs and ASHAs bear the responsibility for immunization services for pregnant women and children, ANC, PNC, basic management of early childhood diseases, and basic services for communicable and non-communicable diseases including disease surveillance. ANMs identify vulnerable populations, assess their needs, and support national and state program activities. Along with ASHAs and AWWs, ANMs organize VHNDs once a month in villages [29].

Community health workers play a vital role in the community by providing access to healthcare especially in the domain of maternal and child health services. There is evidence to suggest that door-to-door counseling and community outreach improved outcomes in health and nutrition behaviors and service uptake such as routine immunization, contraception, and feeding practices of infants and young children [30]. As noted earlier, in the unprecedented times of COVID-19, there was a mandatory lockdown resulting in disruptions in the RMNCH + A services. In this critical situation, the pool of women community health workers was given the additional responsibility of community surveillance by conducting door-to-door visits to identify suspected COVID-19 cases and trace contacts. They were also engaged in providing information about the virus—mode of transmission, symptoms, prevention, and COVID-19 appropriate behaviors. Community health workers were engaged in building community support networks by coordinating with women-led self-help groups (SHGs), youth networks, and gram pradhans (village heads) and in connecting them with essential health resources.

During the pandemic, anganwadi workers were involved in stitching masks for children and pregnant women. In Vizianagaram, Guntur, Kurnool, and Chittoor districts of Andhra Pradesh. Anganwadi workers delivered supplementary nutrition to pregnant and lactating mothers and children below six years of age. In addition to their core mandated responsibilities, anganwadi workers were also involved in ensuring the safety of women during the lockdown. Reports show that there was an increase in domestic violence in this period. The government of Tamil Nadu initiated a response system in which the anganwadi became the first point of contact for receiving calls about domestic violence and referring those to the concerned officials. In the Rajouri district of Jammu and Kashmir, women could register their domestic violence complaints either at the anganwadi center or directly through the distress helpline [29].

Despite the critical role played by frontline women health workers, their own situation had been dismal. Frontline health workers had repeatedly raised their voices regarding inadequate masks, sanitizers, gloves, and personal protective equipment (PPE) kits. In several cases, ASHAs faced violent resistance from the community and so they required protection for their own safety. This was further compounded by delays in receiving their salaries. ASHA workers earn incentives for completing over 60 tasks ranging from Re 1 for every oral rehydration solution (ORS) packet distributed to Rs. 600 for each institutional birth [31]. Due to the pandemic related disruptions in many routine activities related to maternal and child health, ASHAs experienced a decline in their earnings, in some cases to half of their usual income. A study conducted by BehanBox between October and December 2020 on the role of frontline workers fighting the COVID-19 crisis in ten states—Assam, Bihar, Haryana, Jharkhand, Karnataka, Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, Delhi, Telangana, and Uttar Pradesh, revealed that on an average, work hours for ASHAs increased from 6 to 8 to almost 12–15 h a day during the pandemic [32]. Community health workers were overworked and underpaid during the pandemic.

The Gendered Impacts of the Pandemic

Women contribute a predominant share to the ‘care economy’ with almost 75% of unpaid care and domestic work at home [33]. Women also engage in the paid economy with high participation in industries. Several of those industries were affected by the pandemic [34]. It is estimated that in the formal sector, job loss rates were twice as high for women than for men [3]. Globally, in the year 2020, women represented 38.8% of all participants in the labor force [35]. As per the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Center’s Gender Index, globally women engaged three times more in care work than men [36, 37]. It is estimated that in the health sector women contribute 5% to the global gross domestic product (USD 3 trillion) annually, of which almost 50% is unrecognized and unpaid [38]. Occupational de-segregated by gender in the health sector is universally seen with a predominance of women health workers belonging to lower social strata. Therefore, they are paid comparatively less and are often in unpaid roles—facing the harsh realities of gender bias. In the health sector, the gender pay gap exists globally affecting women’s health outcomes. Women in the healthcare sector earn on an average 28% less than men [39]. The occupational distribution of women tends to be skewed in favor of nursing and midwifery and other ‘care’ professions such as community health workers. Globally in 2019, of 28.5 million nurses and midwives, about 24 million were women, making them a key stakeholder in the delivery of health services [38].

In India, female labor force participation was on the decline even in the pre-COVID era. Women’s earnings were about one-fifth of men’s earnings. This situation was further intensified in the informal sector constituting almost 91% of women. Unequal structures, power relations, and societal norms worsened for women during the pandemic. More women lost their jobs and became primary caregivers at home [40]. During the first lockdown in the first quarter of 2020, 47% women lost their jobs and did not return to work by the end of the year as compared to 7% men who lost their jobs and were able to make a recovery. In the informal sector, between March and April 2021, rural women in informal jobs accounted for 80% of the job losses. Overall, in India, the trend shows that men slipped into informal employment while women were forced out of the workforce—further pushing households into poverty and destitution [41].

Extended lockdowns and social distancing norms imposed to curb the pandemic made women more vulnerable to domestic violence. Emerging evidence shows that since the outbreak of COVID-19, reports of violence against women increased in countries where there were lockdowns. Employment insecurity and stress resulted in an increase in gender-based violence. The National Commission for Women (NCW) corroborates that domestic violence complaints almost doubled after the nationwide lockdown was imposed in India. Based on NCW data, a total of 1,477 women complained of domestic violence during the first lockdown between March 25 and May 31, 2021. The highest number of complaints in the last 10 years were recorded in this 68-day period. Among cities, Delhi recorded the highest complaint rate with 32 complaints. Uttar Pradesh recorded the highest number of complaints (600) among all the states in India [42]. Community managed initiatives were undertaken to support civil society organizations along with DAY-NRLM under the Initiative for What Works to Advance Women and Girls in the Economy (IWWAGE). The latter also supported the Study Webs of Active–Learning for Young Aspiring Minds (SWAYAM) Project [43]. A center was established to help women voice their grievances. A physical Lok Adhikar Kendra (Gender Justice Center) was established with the support of the non-governmental organization ANANDI in the Karhal and Sheopur blocks of Sheopur District of Madhya Pradesh. Project Concern International initiated tele-counseling services for women at the Gender Facilitation Center in Odisha [44].

Women-led Initiatives to Enhance Maternal and Child Health Services: The 3R Response

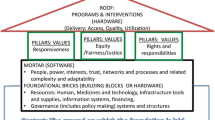

In this section, we showcase the critical role played by women’s groups in underserved and marginalized communities to supplement government efforts to mitigate the health risks of the pandemic. These efforts can be viewed through the lens of a ‘3R response’-Relief, Resilience, and Recovery. We explain this briefly as follows:

-

Relief: from the socio-economic and health impacts of the pandemic

-

Resilience: against the overburdened and overstretched health infrastructure

-

Recovery: from the pandemic induced disruptions in maternal and child health services.

The underlying essence of the ‘3R response’ can be understood through various community initiatives that women proactively initiated to address maternal and child health (MCH) needs at the community level during the COVID-19 pandemic. Through the ‘3R response’, we discuss the proactive, innovative, and dynamic responses to the pandemic by women-led initiatives; resilience through collective solidarity by women’s groups as they selflessly committed themselves to generating awareness about COVID-19 appropriate behaviors and bridging the supply gap for vulnerable populations. We also sustained efforts of women’s groups in facilitating the social and economic recovery of vulnerable populations.

Decentralized and Integrated Ways to Generate COVID-19-Related Awareness at the Grassroot Level

Local responses to the pandemic included generating awareness using creative outlets and digital media. For example, while some SHGs were engaged in graffiti in villages in Chhattisgarh, others made rangoli (colored designs) for sensitizing the public about the virus in Uttar Pradesh [45]. In Uttar Pradesh, SHGs of the State Rural Livelihood Mission (SRLM) ‘Prerna’ marked the roads with rangoli to educate the community about the COVID-19 protocol of physical distancing. They also generated awareness through wall paintings. Women in SHGs used online platforms like TikTok videos and songs to generate awareness about COVID-19 appropriate behavior [46]. In Kerala, Kudumbshree disseminated information and checked for misinformation through WhatsApp groups [47]. In Bihar, JEEViKA used the mobile Vaani platform, an interactive voice response system to spread preventive messages about COVID-19 [47]. JEEViKA SHGs developed an innovative comic series, ‘Badki Didi’ (big sister), for delivering messages on COVID-19 prevention. In Assam, a vehicle with an amplifier was used by the SHGs to spread messages in the community. In Nagaland, SHGs introduced an innovative method to promote hand hygiene in the community by using locally made bamboo poles [43]. In Jharkhand, a group of rural women journalists called Patrakar Didis (journalist sisters) disseminated information on staying safe and accessing healthcare services [43].

SHGs were also involved in enhancing livelihood opportunities for women. In Assam, women were engaged in weaving Gamusa (cotton cloth having a cultural significance) fabric for making masks in anticipation of high sales during Rongali Bihu, an Assamese festival [43]. Similarly, in the Etawah District of Uttar Pradesh, triple layered masks were made from khadi (handloom). In Lucknow, women chikankari (embroidery) artisans were involved in making masks. SHGs in the Narayanpet District of Telangana were engaged in making masks from their traditional fabric, Pochampally. These products were subsequently marketed by the State Rural Livelihoods Missions [48].

Through their vast networks, SHGs were involved in producing 16 million masks, 500,000 L of sanitizers and 500,000 PPE kits. They also promoted 120,000 community kitchens [49]. Community kitchens provided nutritious food to vulnerable populations, especially to pregnant and lactating mothers and children. Various initiatives were seen across states. Jharkhand initiated the Mukhya Mantri Didi Kitchen and Dal Bhaat Kendras that were run by Sakhi Mandals (SHGs) to provide free meals to vulnerable populations. Bihar started the Didi Ki Rasoi and Uttar Pradesh catered to Prerna canteens. In Odisha, around seven million women members of 0.6 million Mission Shakti SHGs provided necessities like dry rations, groceries, and cooked food to vulnerable populations through community kitchens [45]. In Chhattisgarh, SHGs were engaged in making disposable plates and bowls from paper and dried leaves for the quarantine centers [50]. They also prepared and delivered ready-to-eat Poshan (nutrition) kits to pregnant women in quarantine centers in the rural areas of Bemetara District [43].

SHGs also played an instrumental role in crises situations. In Rajasthan, during a crises caused by a drought, the SHG platform was utilized to spread information on capacity building and livelihoods [51, 52]. There are success stories portraying how community-led initiatives for health and food security set an example during the Nipah outbreak in Kerala and cyclone Phani in Odisha [51]. Women’s collectives have a deep understanding of local communities. They are trusted by the communities which enables them to implement successful initiatives at the community level. At the beginning of the pandemic induced lockdown in India, women SHGs were agile and proactive in pivoting COVID-19 crisis management by reaching out to the last mile and using their social capital to support communities [46]. During the peak of the lockdown, women’s collectives, in the form of SHGs, rose to the occasion to provide a decentralized and integrated approach for addressing the health needs of the community. This included generating awareness among pregnant and lactating women as well as among other vulnerable groups to follow COVID-19 protocols and stay safe. They helped in providing nutrition and health services that had been disrupted during the pandemic.

SHG and Their Federations in Disseminating MCH and Nutrition Messages in the Community

In 2011, as part of the National Rural Livelihood Mission, the SHGs and their federations, which were functioning with the support of non-governmental organizations, got a structured government platform. In 2015, the Mission was renamed as Deendayal Antyodaya Yojana National Rural Livelihoods Mission. The aim of the Mission is to reduce poverty through gainful self-employment of women. There are 89.91 million households that are mobilized into 8.34 million SHGs. They work across 742 districts and 7073 blocks in 34 states and union territories of India [53].

A systematic review shows that participatory learnings and actions are a cost-effective strategy for improving maternal and neonatal survival in low-resource settings [54]. Studies in India show that health interventions with women’s groups such as SHGs and their federations helped in improving maternal and child health practices that are supply independent through health behavior change communication interventions [55]. A quasi-experimental study in Uttar Pradesh showed that discussions on key maternal and newborn health practices by trained peer-educators in SHG meetings and community outreach activities organized by SHGs and their federations helped women follow correct healthcare practices [56]. Studies in Bihar demonstrated the effects of pilot interventions around behavior change communication through women’s SHGs on improving healthy practices [57, 58]. In three states of India—Bihar, Chattisgarh, and Odisha—Swabhimaan, an initiative integrated within the Government of India’s flagship poverty alleviation program-Deendayal Antyodaya Yojana-National Rural Livelihoods Mission (DAY-NRLM) aims to mobilize women through SHGs to address the nutritional needs of adolescents and women in their communities. Findings from its mid-line evaluation revealed a reduction in thinness among adolescent girls and in women with children under two years of age and an increase in the average mid-upper arm circumference of pregnant women [59].

SHGs were engaged in developing nutri-gardens to promote sustainable ways to boost the immunity of the women and children. This was done by encouraging women to have kitchen gardens in their backyards. They were encouraged to sow different vegetables to address the nutritional needs of pregnant and lactating women and children aged six months to three years. Under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA), women farmers encouraged families with pregnant women to develop nutri-gardens in their homes in the Koraput District of Odisha [48]. The NRLM advised that Krishi Sakhis (agricultural community resource women) support women in making their own kitchen gardens and also engage in poultry as sustainable ways to address their nutritional needs [43]. In Bihar, JEEViKA SHGs distributed seeds to households with pregnant women and children who had kitchen gardens. Similarly, in Jharkhand, seeds of pulses and cereals were provided to SHGs. In a few blocks of the Deoghar District in Jharkhand, the district administration distributed sewing machines to women for weaving fishing nets [43].

Another innovative initiative that was undertaken during the lockdown was ‘Vegetables on Wheels’. Women in SHGs took it upon themselves to reach fresh vegetables to the vulnerable especially new mothers and children. Kudumbashree started ‘floating supermarkets’ in the Alappuzha District in the backwaters and canals for delivering essential goods. Five members of two Kudumbashree units started operating a ‘supermarket’ ferry to provide essential daily food supplies. They raised about USD 2,000 for procuring supplies [60]. Ferrying on the Pampa river, the supermarket catered to over one hundred families in Kuttanad. In Mizoram, community-operated transport vehicles were used for providing essential services and commodities to underserved areas [48]. In the Bastar District of Chhattisgarh, Poshan Sakhis (nutrition sisters) started a tele-counseling service for women on COVID-19 appropriate behaviors, hygiene, and healthy diets. They organized monthly review meetings to assess if appropriate nutrition was being made available during the lockdown to pregnant women, lactating mothers, and children [43].

Extending Support to Community Health Workers for Delivering Maternal and Reproductive Health Services

The lockdown saw a suspension of reproductive, maternal, newborn, child, and adolescent health (RMNCH + A) services across various states of the country. Because anganwadi centers were closed, SHGs and other women’s collectives stepped in to ensure that pregnant and lactating mothers and children received the services that they needed. Apart from addressing their nutritional needs, SHGs also supported the over-burdened frontline health workers to provide ANC and PNC. They provided iron and folic acid and calcium supplements to women. More than 4,000 pregnant and lactating mothers were reached by over 2,000 SHGs in the states of Bihar, Odisha, and Chhattisgarh. As part of the ‘Take Home Ration’ (THR) Program, SHGs supported AWWs, ASHAs, and ANMs in Odisha and Chhattisgarh to distribute eggs to children below five years of age and to pregnant and lactating mothers [44]. In some blocks of Odisha, SHGs served the community by tracking pregnant women, lactating mothers, and children to provide routine immunization [61]. They contacted pregnant women who were due for ANC check-ups and extended their support in facilitating ANC visits at health centers [43]. Kudumbashree in Kerala ensured that the health supplement Amrutham Nutrimix powder reached all infants and children across all the districts of Kerala [43]. The Swabhimaan Projects in Bihar, Odisha, and Chhattisgarh was run by the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and the ROSHNI Center for Women Collectives Led Social Action where frontline health workers were supported by SHGs for the delivery of ANC and PNC and for providing micronutrient supplements to under-nourished pregnant women and lactating mothers [44].

Poshan sakhis in Bastar, Chhattisgarh worked closely with ASHAs, ANMs, and Anganwadi workers in providing counseling on nutritional practices to adolescent girls, pregnant women, and mothers of children under two years of age. They also monitored the beneficiaries receiving essential nutrition services like THR as well as micronutrient supplementation such as iron and folic acid (IFA) and calcium at VHNDs. Poshan sakhis in Chhatisgarh and Odisha distributed sanitary napkins, soap, and sanitizers to adolescent girls and generated awareness regarding hand washing with soap [62]. In the Angul District of Odisha, poshan sakhis mobilized communities to observe VHNDs while wearing masks and maintaining social distancing [61]. In the Purnea District of Bihar, kishori sakhis were engaged in working with adolescent girls through participatory learning and action (PLA) sessions on hygiene and hand washing to prevent COVID-19 infection [43].

Closely associated with SHGs, poshan sakhis (friends of nutrition) in Bihar, Chhattisgarh, and Odisha aimed to improve the nutritional status of girls and women through a life cycle approach—starting before conception and ending after childbirth. This included ANC and PNC services and providing micronutrient supplements to malnourished pregnant and lactating mothers [44].

Women in SHGs in Maharashtra distributed sanitary pads through Asmita Plus to help meet the demand for sanitary pads during the lockdown. During the lockdown, an SHG from Pune, Gyaneshwari Samuh Sahayata Samuh supplied 10,000 packets of Asmita Plus sanitary pads to the Shindhwane gram panchayat [62]. SHGs under the Chhattisgarh Rural Livelihoods Mission, Bihar Horticulture, Agriculture (BIHAN)—prioritized the distribution of sanitary pads. SHGs also worked very closely with other government initiatives in delivering services to the community during the lockdown. They put their own health at risk as they distributed rations under the Public Distribution System and Take-Home Rations Project implemented through ICDS program [62].

Addressing Breastmilk Pleas: Women’s Initiatives

Collaborating with the government, development agencies and civil society organizations provided pathways and opportunities to further the efforts of the women collectives to overcome pandemic related barriers. The second wave of COVID-19 in the country was characterized by a huge shortage of oxygen cylinders, beds, and medications. Thousands of families lost their loved ones. Several pregnant women and new mothers infected; some succumbed to the virus. This led to an increase in pleas for breastmilk. Several community-led organizations came forward to address this concern. Lactating mothers came together voluntarily to support families individually or through human milk banks. Some prominent NGOs, such as Bachpan Bachao Andolan and Protsahan India Foundation, made efforts to ensure that breastmilk was available to infants in rural and urban areas in the midst of the COVID-19 crisis [63].

In the digital domain, women-led initiatives like Prachi Pendurkar’s Snugbub and Adhunika Prakash’s Facebook group Breastfeeding Support for Indian Mothers posted COVID-related posts on social media for those who were asked to isolate from their babies. Doctors in Mumbai conducted online training in safe breastfeeding for anganwadi supervisors in rural Maharashtra. They also set up a helpline for mothers to address their questions on breastfeeding. In addition, they developed a series of Do-It-Yourself tutorials for new mothers [64].

Some state governments also launched initiatives to support breastfeeding. The Delhi Commission for Protection of Child Rights launched a helpline to support children whose caretakers were not available owing to COVID-19 and offered to connect them to women who could donate breast milk. Kerala launched the state’s first human milk bank called ‘Nectar of Life’ at the Ernakulam General Hospital. This facility ensured the availability of abundant breast milk for newborns who could not be breastfed by their own mothers because they were deceased, unwell, or unable to produce sufficient milk [65].

Conclusion

While we recognize the gendered nature and impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, we celebrate the resilience, commitment, and perseverance shown by women-led initiatives in India. Women-led collectives played a critical role in bridging development deficits that were further exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. We believe that the India story was characterized by the ‘3R response’-Relief, Resilience, and Recovery, led by community women to protect vulnerable groups including pregnant women, lactating mothers, and children who could not receive essential services during the COVID-19 pandemic. The ‘3R response’ can serve as a model in other crisis situations. Women-led initiatives, especially at the grassroots, were able to amplify the voices and priorities of vulnerable groups by bringing them and their concerns center stage. In addition, women’s collectives emerged as a sustainable, inclusive, and self-governing community. They demonstrated the effectiveness of participatory development and decentralized governance for building a sustainable gender responsive environment to address the ante-natal and nutritional needs of pregnant women, lactating mothers, and children. Throughout the COVID-19 crisis and the associated lockdowns, these women’s groups consistently demonstrated proactive and swift responses and resilience through their selfless dedication and altruism to meet the needs of vulnerable women and children. Pan India narratives of efforts and initiatives of women’s collectives discussed in this chapter illustrate that women’s leadership can offer hope in times of the COVID-19 humanitarian crisis and beyond—that no matter how troubled the waters are, women champions will continue to build bridges—longer, higher, and stronger—and create pathways for sustainable and inclusive development by serving the underserved and most vulnerable.

References

Global Health 50/50 (2020) COVID-19 sex-disaggregated data tracker 2020. The Sex, Gender AND COVID-19 Project. https://globalhealth5050.org/the-sex-gender-and-covid-19-project/the-data-tracker/

Smith J (2019) Overcoming the ‘tyranny of the urgent’: integrating gender into disease outbreak preparedness and response. Gender, Development. 27(2):355–369. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552074.2019.1615288

United Nations (2020) The Impact of COVID-19 on women 2020. Sexual Violence in Conflict, United Nations. https://www.un.org/sexualviolenceinconflict/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/report/policybrief-the-impact-of-covid-19-on-women/policy-brief-the-impact-of-covid-19-on-women-en-1.pdf

Azcona G, Bhatt A, Encarnacion J, Plazaola-Castaño J, Seck P, Staab S, Turquet L (2020) From insights to action: Gender equality in the wake of COVID-19: United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women (UN Women). https://eca.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2020/09/gender-equality-in-the-wake-of-covid-19-0

Ryan NE, El Ayadi AM (2020) A call for a gender-responsive, intersectional approach to address COVID-19. Global Public Health. 15(9):1404–1412. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2020.1791214

Joint statement by ILO, FAO, IFAD, WHO. Impact of COVID-19 on people's livelihoods, their health and our food systems. World Health Organization. 2020. https://www.who.int/news/item/13-10-2020-impact-of-covid-19-on-people's-livelihoods-their-health-and-our-food-systems

Singh S, Singh AK, Jain PK, Singh NP, Bajpai PK, Kharya P (2020) Coronavirus: A threat to global public health. Indian J Commun Health. 2020; 32(1):19–24. https://iapsmupuk.org/journal/index.php/IJCH/article/view/1356

Horton R (2020) Offline: COVID-19 and the NHS—“a national scandal.” The Lancet 395(10229):1022

World Health Organization. Pulse survey on continuity of essential health services during the COVID-19 pandemic: interim report. World Health Organization. 2020 Aug 27. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-EHS_continuity-survey-2020.1

Townsend R, Chmielewska B, Barratt I, Kalafat E, van der Meulen J, Gurol-Urganci I, O'Brien P, Morris E, Draycott T, Thangaratinam S, Doare KL, Ladhani S, Dadelszen PV, Magee LA, Khalil Al. Global changes in maternity care provision during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine. 2021; 37:100947. https://www.research.ed.ac.uk/en/publications/global-changes-in-maternity-care-provision-during-the-covid-19-pa

Burki T. The indirect impact of COVID-19 on women. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2020; 20(8):904–905. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7836874/

Roberton T, Carter ED, Chou VB, Stegmuller AR, Jackson BD, Tam Y, Levis TS, NeffWalker. Early estimates of the indirect effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and child mortality in low-income and middle-income countries: a modelling study. The Lancet Global Health. 2020 May 12. 8(7):e901-e8. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/langlo/article/PIIS2214-109X(20)30229-1/fulltext

Khalil A, Von Dadelszen P, Draycott T, Ugwumadu A, O’Brien P, Magee L. Change in the incidence of stillbirth and preterm delivery during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Americal Medical Association. 2020; 324(7):705–706. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2768389

Been JV, Ochoa LB, Bertens LC, Schoenmakers S, Steegers EA, Reiss IK. Impact of COVID-19 mitigation measures on the incidence of preterm birth: A national quasi-experimental study. The Lancet Public Health. 2020; 5(11):e604-e11. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33065022/

Chmielewska B, Barratt I, Townsend R, Kalafat E, van der Meulen J, Gurol-Urganci I, O'Brien P, Morris E, Draycott T, Thangaratinam S, Doare KL, Ladhani S, Dadelszen PV, Magee L, Khalil A.. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and perinatal outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Global Health. 2021 Mar 31. https://europepmc.org/article/pmc/8012052

Khalil A, von Dadelszen P, Kalafat E, Sebghati M, Ladhani S, Ugwumadu A, Draycott T, O'Brien P, Magee L, on behalf of the PregnaCOVID3 study group. Change in obstetric attendance and activities during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2021 Oct 05; 21(5):e115. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7535627/

Lawn JE, Blencowe H, Waiswa P, Amouzou A, Mathers C, Hogan D, Flenady V, Froen JF, Qureshi ZU, Calderwood C, Shiekh S, Jassir FB, You D, McClure EM, Mathai M, Cousens S, Lancet Ending Preventable Stillbirths Series Study Group, Lancet Stillbirth Epidemiology Investigator Group. Stillbirths: rates, risk factors, and acceleration towards 2030. The Lancet. 2016 Feb 06; 387(10018):587–603. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26794078/

Pattinson R, Kerber K, Buchmann E, Friberg IK, Belizan M, Lansky S, Weissman E, Mathai M, Rudan I, Walker N, Lawn JE, Lancet's Stillbirths Series Steering Committee. Stillbirths: How can health systems deliver for mothers and babies? The Lancet. 2011 May 07; 377(9777):1610–1623. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21496910/

Busch-Hallen J, Walters D, Rowe S, Chowdhury A, Arabi M. Impact of COVID-19 on maternal and child health. The Lancet Global Health. 2020 Aug 08; 8(10):e1257. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7398672/

Victora CG, Christian P, Vidaletti LP, Gatica-Dominguez G, Menon P, Black RE. Revisiting maternal and child undernutrition in low-income and middle-income countries: variable progress towards an unfinished agenda. Lancet. 2021 Apr 10; 397(10282):1388–1399. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33691094/

Headey D, Heidkamp R, Osendarp S, Ruel M, Scott N, Black R, Shekar M, Bouis H, Flory A, Haddad L, Walker N, Standing Together for Nutrition Consortium. Impacts of COVID-19 on childhood malnutrition and nutrition-related mortality. The Lancet. 2020 Aug 22; 396(10250):519–521. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)31647-0/fulltext

Laborde D, Martin W, Vos R. Poverty and food insecurity could grow dramatically as COVID-19 spreads. International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), Washington, DC. 2020 Apr 16. https://www.ifpri.org/blog/poverty-and-food-insecurity-could-grow-dramatically-covid-19-spreads

Government of India, Ministry of Health, Family Welfare. A strategic approach to reporoductive, maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health (RMNCH+A) in India. Government of India, Ministry of Health, Family Welfare. 2013 Jan. https://nhm.gov.in/images/pdf/RMNCH+A/RMNCH+A_Strategy.pdf

Taneja G, Sridhar VS-R, Mohanty JS, Joshi A, Bhushan P, Jain M, Gupta S, Khera A, Kumar R, Gera R. India’s RMNCH+ A strategy: Approach, learnings and limitations. BMJ global health. 2019 May 09; 4(3):e001162. https://gh.bmj.com/content/bmjgh/4/3/e001162.full.pdf

International Institute for Population Sciences. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5) 2019–21: India Fact Sheet 2021. International Institute for Population Sciences. http://rchiips.org/nfhs/pdf/NFHS4/India.pdf

Scroll.in. COVID-19 has disrupted India's routine health services and that could have long-term consequences. Scroll.in. 2020 Sep 01. https://scroll.in/article/971655/covid-19-has-disrupted-indias-routine-health-services-and-that-could-have-long-term-consequences

PATH. RMNCAH-N Services During COVID-19: A spotlight on India’s policy responses to maintain and adapt essential health services 2020. PATH. 2021 Feb. https://path.azureedge.net/media/documents/India_RMNCH_Deep_Dive_brief.pdf

Jain I. Harbingers of Hope: Giving ASHA workers their due to build a resilient maternal and child health system in post-covid-19 India. PLOS. 2021 Jun 02. https://yoursay.plos.org/2021/06/harbingers-of-hope-giving-asha-workers-their-due-to-build-a-resilient-maternal-and-child-health-system-in-post-covid-19-india/

KPMG. Response to COVID-19 by the Anganwadi ecosystem in India 2020. KPMG. 2020. https://assets.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/in/pdf/2020/06/anganwadi-report-2020.pdf

Nanda P, Lewis TN, Das P, Krishnan S. From the frontlines to centre stage: resilience of frontline health workers in the context of COVID-19. Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters. 2020; 28(1):1837413. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33054663/

Naandika Tripathi NT. ASHA workers: The underpaid, overworked, and often forgotten foot soldiers of India. Forbes India. 2021 Jul 26. https://www.forbesindia.com/article/take-one-big-story-of-the-day/asha-workers-the-underpaid-overworked-and-often-forgotten-foot-soldiers-of-india/69381/1

Behanbox. Female frontline community healthcare workforce in India during COVID-19. Behanbox. 2021. https://behanbox.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/APU-Report-Final.pdf

Power K. The COVID-19 pandemic has increased the care burden of women and families. Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy. 2020; 16(1):67–73. https://cieg.unam.mx/covid-genero/pdf/reflexiones/academia/the-care-burden.pdf

Madgavkar A, White O, Krishnan M, Mahajan D, Azcue X. COVID-19 and gender equality: Countering the regressive effects. McKinsey, Company. 2020 Jul 15. https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/future-of-work/covid-19-and-gender-equality-countering-the-regressive-effects

The World Bank. Labor force, female (% of total labor force), world. In: The World Bank Databank, editor. 2020. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.TLF.TOTL.FE.ZS

OECD Development Centre. Unpaid Care Work: The missing link in the analysis of gender gaps in labour outcomes. OECD Development Centre. 2014 Dec. https://www.oecd.org/dev/development-gender/Unpaid_care_work.pdf

Katherine H. What are women’s empowerment collectives and how are they helping women weather COVID-19? The Bill, Melinda Gates Foundation. 2021 Apr 02. https://www.gatesfoundation.org/ideas/articles/womens-empowerment-collectives-COVID

Ghebreyesus TA. Female health workers drive global health: We will drive gender-transformative change. World Health Organization. 2019 Mar 20. https://www.who.int/news-room/commentaries/detail/female-health-workers-drive-global-health

World Health Organization. Delivered by women, led by men: A gender and equity analysis of the global health and social workforce. World Health Organization. 2019. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/311322/9789241515467-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

UN Women. From immediate relief to livelihood support, UN Women drives investment and support for women and girls impacted by COVID-19 in India. UN Women. 2021 Jun. https://www.unwomen.org/en/news/stories/2021/6/news-driving-investment-and-support-for-women-and-girls-impacted-by-covid-19-in-india

Azim Premji University. State of Working India 2021: One year of Covid-19, Centre for Sustainable Employment: Azim Premji University. 2021. https://cse.azimpremjiuniversity.edu.in/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/SWI2021_Executive-Summary_August.pdf

Vignesh R, Sumant S, Singaravelu N. Domestic violence complaints at a 10-year high during COVID-19 lockdown. The Hindu. 2020 Jun. https://www.thehindu.com/data/data-domestic-violence-complaints-at-a-10-year-high-during-covid-19-lockdown/article31885001.ece

IWWAGE. Community and Institutional Response to COVID-19 in India: Role of Women’s Self-Help Groups and National Rural Livelihoods Mission. IWWAGE. 2020. https://iwwage.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Swayam-Report.pdf

Press Information Bureau. Community Kitchens run by SHG women provide food to the most poor and vulnerable in rural areas during the COVID-19 lockdown: Press Information Bureau, Government of India. 2020 Apr 13. https://rural.nic.in/en/press-release/community-kitchens-run-shg-women-provide-food-most-poor-and-vulnerable-rural-areas

Press Trust of India. SHGs in Chhattisgarh make face masks, sanitisers to tackle shortage. Press Trust of India. 2020 Apr 02. https://yourstory.com/herstory/2020/04/chattisgarh-shgs-face-masks-sanitisers-coronavirus/amp

Kejriwal N. Covid-19: In times of crisis, women self-help groups lead the way. Hindustan Times. 2020 May 03. https://www.hindustantimes.com/analysis/covid-19-in-times-of-crisis-women-self-help-groups-lead-the-way/story-SyXJVNPLUdVbSljkeaeszN.html

Press Information Bureau. NRLM Self Help Group network rises to the challenge of COVID-19 situation in the country; SHG women use innovative communication and behaviour change tools to generate awareness and help containment of the COVID-19 infection. Press Information Bureau. 2020 Apr 12. https://pib.gov.in/PressReleseDetailm.aspx?PRID=1613605

Tankha R. Women’s Leadership in COVID-19 Response: Self-help Groups of the National Rural Livelihoods Mission Show the Way. Economic and Political Weekly. 2021; 56(19). https://www.epw.in/engage/article/womens-leadership-covid-19-response-self-help

Government of India. DAY-NRLM Dashboard. Government of India. https://nrlm.gov.in/dashboardForOuter.do?methodName=dashboard

Outlook. Chhattisgarh: Women SHGs make 39 lakh masks, 10000 litre sanitizer Raipur: PTI. Outlook. 2022 Mar 11. https://www.outlookindia.com/newsscroll/%20cgarh-women-shgs-make-39-lakh-masks-10000-litre-sanitiser/1839195

Siwach G, Desai S, de Hoop T, Paul S, Belyakova Y, Holla C. SHGs and Covid-19: Challenges, engagement, and opportunities for India’s National Rural Livelihoods Mission. Evidence Consortium on Women's Groups. 2020 Jun 18. https://womensgroupevidence.org/shgs-and-covid-19-challenges-engagement-and-opportunities-indias-national-rural-livelihoods-mission

Barooah B, Sarkar R, Siddiqui Z. It’s time to take note of the Self Help Groups’ potential. International Initiative for Impact Evaluation. 2020 Jun 02. https://www.3ieimpact.org/blogs/its-time-take-note-self-help-groups-potential

Aajeevika. Deendayal Antyodaya Yojana- National Rural Livelihoods Mission. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. https://aajeevika.gov.in/

Prost A, Colbourn T, Seward N, Azad K, Coomarasamy A, Copas A, Houweling TAJ, Fottrell E, Kuddus A, Lewycka S, MacArthur C, Manandhar D, Morrison J, Mwansambo C, Nair N, Nambiar B, Osrin D, Pagel C, Phiri T, Anni-Maria P-B, Rosato M, Jolene S-W, Saville N, More NS, Shrestha B, Tripathy P, Wilson A, Costello A (2013) Women’s groups practising participatory learning and action to improve maternal and newborn health in low-resource settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet 381(9879):1736–1746

Desai S, Misra M, Das A, Singh RJ, Sehgal M, Gram L, Kumar N, Prost A (2020Dec) Community interventions with women’s groups to improve women’s and children’s health in India: A mixed-methods systematic review of effects, enablers and barriers. BMJ Glob Health 5(12):e003304

Hazra A, Atmavilas Y, Hay K, Saggurti N, Verma RK, Ahmad J, Kumar S, Mohanan PS, Mavalankar D, Irani L (2020) Effects of health behaviour change intervention through women’s self-help groups on maternal and newborn health practices and related inequalities in rural India: a quasi-experimental study. EClinical Med 18:100198

Saggurti N, Atmavilas Y, Porwal A, Schooley J, Das R, Kande N, Irani L, Hay K (2018) Effect of health intervention integration within women's self-help groups on collectivization and healthy practices around reproductive, maternal, neonatal and child health in rural India. PLoS One 13(8):e0202562

Saggurti N, Porwal A, Atmavilas Y, Walia M, Das R, Irani L (2019) Effect of behavioral change intervention around new-born care practices among most marginalized women in self-help groups in rural India: analyses of three cross-sectional surveys between 2013 and 2016. J Perinatol 39(7):990–999

Shrivastav M, Saraswat A, Abraham N, Reshmi R, Anand S, Purty A, Xaxa RS, Minj J, Mohapatra B, Sethi V (2021) Early lessons from Swabhimaan, a multi-sector integrated health and nutrition programme for women and girls in India. Field Exchange. 103

Paul S (2020) In Alappuzha, floating supermarket brings essentials to the doorstep of lockdown-affected: The Hindu. https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/kerala/floating-supermarket-brings-essentials-to-the-doorstep-of-lockdown-affected/article31264618.ece

Salve P (2020) Essential outreach services hit in states with worst health indicators. IndiaSpend. https://www.indiaspend.com/essential-outreach-services-hit-in-states-with-worst-health-indicators/

Government of India. COVID-19 response by women SHG Warriors: Ministry of Rural Development, Government of India. 2020. https://aajeevika.gov.in/sites/default/files/nrlp_repository/COVID-19%20Response%20by%20Women%20SHG%20Warriors.pdf

Bhattacharjee N, Sethuraman NR, Monnappa C. Pleas for help in India as COVID-19 leaves children without carers: Reuters. 2021 May. https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-health-coronavirus-india-children-idUKKBN2CN14E

Bhatt N (2020) Breastfeeding in India is disrupted as mothers and babies are separated in the pandemic. British Med J 370

The Hindu. State’s first human milk bank opened. The Hindu. 2021 Feb 06. https://www.thehindu.com/news/cities/Kochi/states-first-human-milk-bank-opened/article33763947.ece

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Kant, A., Hazra, A. (2023). Bridge Over Troubled Waters: Women-led Response to Maternal and Child Health Services in India Amidst the COVID-19 Pandemic. In: Pachauri, S., Pachauri, A. (eds) Global Perspectives of COVID-19 Pandemic on Health, Education, and Role of Media. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-1106-6_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-1106-6_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-99-1105-9

Online ISBN: 978-981-99-1106-6

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)