Abstract

Although harnessing full community participation in natural resource management produces positive ecological and economic outcomes, the specific roles of men and women in peatland communities are often overlooked. This study investigates the differentiated knowledge and roles of both men and women in peatland management in Rantau Baru, a fishing and farming Peat Care Village (Desa Peduli Gambut) in Riau Province, Indonesia. Primary data were collected through a survey of 152 households conducted from January–February 2020 and subsequent follow up interviews with community members. Modifying the Harvard Analytical Framework, the study examines knowledge levels of men and women as well as productive (peatland cultivation and fishery) activity, reproductive or domestic (childcare and household finance) activity, and sociopolitical (community meetings) activity. It finds that men are significantly more knowledgeable about peatlands than women and that peatland agricultural activities are dominated by men, but that gender roles are more evenly distributed in fishery activities. Women and men play complementary roles in “reproductive activities” of the household, but women do not participate nearly as much as men in the public sphere of “sociopolitical activities,” such as attending community, association, and village meetings. The study provides new insight into the community’s knowledge of peatland according to gender, and the potential role of both male and female community members in peatland restoration. Any project or program on peatland restoration should recognize the basic features and differences of gender roles and the specific needs of men and women to ensure the optimal contribution of all community members to peatland management and restoration.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

7.1 Introduction

Peatland restoration aims not only to rehabilitate the ecological functions of peatlands, but also, increasingly, to improve the welfare of the communities surrounding peatlands. Community involvement in peatland restoration is expected to create sustainable peatlands by increasing welfare and ecological function (Safitri 2020), and research has shown that improving local livelihoods and involving community members in restoration efforts results in better outcomes for sustainable peatland restoration. Ensuring the involvement of all community members requires the participation of both men and women, yet peatland restoration programs often overlook the gender dimension of peatland management.

Various international organizations, including the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) ( 2012), the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UN ESCAP) ( 2017), and the World Bank (2018), and scholars such as Elmhirst (1998), Resurreccion (2008), and Watson (2006) recognize and promote the importance of gender and gender analysis in natural resource management. Elmhirst and Resurreccion (2008, p. 5) assert that “men and women hold gender-differentiated interests based on their distinctive roles, responsibilities, and knowledge” and therefore, “gender is a critical analytical concept for understanding the social and political dimensions of natural resource management and governance across a range of empirical settings” (Elmhirst and Resurreccion 2008, p. 3). WWF (2012) recognizes the need for gender sensitivity in natural resource management to ensure that projects and programs recognize the different roles and needs of men and women.

A considerable number of studies have also been conducted on women’s roles in the agricultural and rural development of Indonesia. In discussing agricultural production in Java, Sajogyo (1983) focuses on women’s time allocation in productive, reproductive, and decision-making work. Widiarti and Hiyama (2007)‘s study of Citarik Village, Sukabumi, West Java demonstrates the considerable contribution of women in the Pengelolaan Hutan Bersama Masyarakat (PHBM), or Joint Forest Management Program, in land clearing, planting, and plant maintenance. Although some women decided to join the PHBM without their husband’s permission, the study found that women’s decision-making power within the family does not translate to the community level, because the decision-makers in village meetings are men, and women’s access to knowledge is limited, as only men attend trainings (Widiarti and Hiyama 2007). Mugniesyah and Mizuno’s study (2007) of women’s access to land and their control over it in Sundanese communities with bilateral kinship systems reveals that: (1) These communities follow sanak values (customary law), a set of values concerning gender equity and the rights of sons and daughters to the household property and sanak values strongly influence peasant households in the allocation of their land through inheritance and grant systems; (2) sanak values lead to gender equality in access to and control over land among household members; and (3) gender equality in land ownership is also shown in the practice of the inheritance system, which is calculated through both the male and female lines. Using the Harvard Analytical Framework, Dewi et al. (2020) analyze the role of male and female farmers in the Special Purpose Forest Area of Parungpanjang, West Java and discover that: (1) Female farmers participate in all dimensions of productive, reproductive, and sociopolitical activities, while male farmers tend to limit their participation only to productive and sociopolitical activities; (2) the Special Purpose Forest Area of Parungpanjang does not grant official rights to female farmers to use the land (only a male head of household can register for such rights); and (3) gender-responsive policies and gender awareness programs among male farmers need to be strengthened. Studies on gender and natural resource management outside Java include Elmhirst et al. (2017), which examines oil palm plantations in Kalimantan through a feminist political ecology perspective. Other scholars, such as Villamor et al. (2015) and Villamor et al. (2014), analyze gender and land use change in Central Sumatra.

Despite the rich literature on gender and natural resource management, however, very little of it deals with peatland management specifically. Conversely, among the numerous studies devoted to understanding peatland restoration and management in Indonesia (such as Mizuno et al. 2016), few explore women’s roles in these processes. Exceptions to this include Subono et al. (2020), which focuses on the involvement of women in peatland restoration in Central Kalimantan Province and finds that although women facilitators faced structural and cultural obstacles, an economic revitalization program they implemented strengthened the economic resilience of rural women’s communities and changed gender relations. In a study of women’s experiences in Central Kalimantan and Riau, Indirastuti (2020) reveals that although firefighting requires women’s involvement, especially when it happens on their land or in their living spaces, women do not have access to the resources they need to prevent and fight forest and land fires.

Perhaps the most comprehensive study to date of gender roles in peat-based communities in Riau is Herawati et al. (2019). Modifying the Harvard Analytical Framework, it used a mix of qualitative and quantitative methods to study gender roles and livelihoods in seven villages and three districts of Riau Province from 2016 to 2018. It found that: (1) agricultural activities are significantly dominated by men, while women play a more significant role in domestic activities; (2) both men and women contribute equally to the social life of the community, in which women’s participation and group membership is equal to men’s; (3) low-income families tend to have higher gender equity in agricultural activities than high-income households; (4) the role of women in wealthier households is not in their physical contribution to the land, but is mostly in their role as decision-maker, indicating that women play a significant role in the livelihoods of both poor and rich families, but in different forms; and (5) community development interventions that involve women are recommended (Herawati et al. 2019).Footnote 1

Indonesia’s Peatland Restoration Agency, the Badan Restorasi Gambut (BRG), carries out peatland restoration through the 3-R method, that is, by rewetting and replanting peatlands and by revitalizing the livelihoods of local communities (BRG 2018, p. 1). The BRG mobilizes community participation in peatland restoration through its Kerangka Pengaman Sosial (Social Safeguard Framework) and the Peat Care Village Program. Riau Province is one of the seven provinces targeted by the BRG for priority peatland restoration,Footnote 2 which stipulates that the area contains Peat Hydrological Units (Kesatuan Hidrologis Gambut, KHG) (BRG 2018, p. 1). As of 2019, there were 262 Peat Care Village Programs across the seven KHGs, with 49 located in Riau Province (BRG 2019a, p. 27). The BRG’s Deputy Section for Education, Socialization, Participation, and Partnership has given special attention to women’s roles and participation in peatland restoration. For example, 773 women’s groups in Kalimantan have received assistance from the BRG to increase the added value of woven handicraft products made from grass or plants that mostly grow on peatlands (Sumartomjon 2019). This example illustrates how the BRG strives to provide gender-specific programs, an approach that aligns with global efforts that recognize the significance of the gender dimension in natural resource management. However, the specific contributions and potential of men and women remain under studied.

Given the lack of gender analysis in existing peatland literature and programming, this chapter examines the gender dimension more fully, providing new data and insights on community participation in peatland management in Riau, the center of peatland restoration in Indonesia. As a case study, it investigates the role of community members (both men and women) in peatland management in Rantau Baru, a designated Peat Care Village. The study sheds light on (1) the different levels of knowledge among men and women of gambut, or peatland, the sources of their knowledge, and involvement in training/socialization on peatland conservation, and (2) the roles of women and men (as farmers and fishers) in peatland management in Rantau Baru Village. By providing a more comprehensive understanding of male and female roles in peatland management in a Peat Care Village, it is hoped that the study can contribute to formulating more effective peatland programming that is suitable for all community members.

7.2 Method

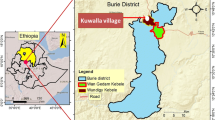

7.2.1 Research Site: Location, Livelihoods, Population Make-Up

Rantau Baru Village has been introduced in earlier chapters of this book. It is located in Riau Province, which has the largest peatland area in Sumatra (Muslim and Kurniawan 2008, p. 1), and in the Kiyap River KHG.Footnote 3 As it is on the edge of the Kampar River, the village is often flooded. This was observed by the author and research team in December 2018 as seen in Fig. 7.1. Such floods block access to the main road of the village and submerge the village entrance gate (pictured in green). Thus, during the flood season, often the only way to enter the village is by small boat through the sekat kanal (a canal bulkhead that also functions to prevent peatland fires), which runs parallel to the main road. It takes approximately 40 min to reach the village center from the entrance gate with this transport.

Rantau Baru Village is a fishing and farm-based community. As explained in Chaps. 4 and 5, the peat swamp forests are fishing grounds for communities living in the area. The presence of peasant fishermen among Malay (Melayu) Indonesians was recorded by Firth’s study in 1946 (Firth 1946). Thus, the livelihood makeup of Rantau Baru Village is not surprising.

The total population of Rantau Baru Village in 2019 was 715 people, consisting of 379 men and 336 women living in 206 kepala keluarga, or households (BRG 2019b, p. 25). The majority of the population is Muslim; only five people adhere to Catholicism (BRG 2019b, p. 35). According to the village secretary, the community’s origins are rooted in suku Minangkabau, or the Minangkabau lineage (interview, December 9, 2018), although the validity of this oral explanation still needs to be verified. In Chap. 3, Osawa and Banawan postulate that local people are descended from the intermingling of the Minangkabau, coastal Malays, and indigenous peoples who lived in the region prior to the arrival of these two groups.

The matrilineal society of the Malay Petalangan people in Rantau Baru Village, who make up 30% of the population, consists of transgenerational links through the maternal line, by which ancestral land and land rights pass from grandmother to mother, and then to granddaughter and her descendants in the female line (interview with village secretary, December 9, 2018). Moreover, each Sialang tree, where honeybees make their nests, is highly regarded by the Malay Petalangan and is passed down from generation to generation through the female line (BRG 2019b, p. 37). Another characteristic of the Malay Petalangan’s matrilineal society is the ninik mamak, or a male chief of the lineage, and kepala suku, or “prominent respected men” (BRG 2019b, p. 38; interview with the ninik mamak of Rantau Baru, December 2, 2020).

7.2.2 Research Methodology

This study relies primarily on data from a survey of all households in the village conducted during January–February 2020. The survey data is based on the responses of 77 women and 75 men. The survey was preceded by preliminary observations and interviews in the village in December 2018 and from August to September 2019. Following the survey, follow-up interviews were conducted online from November to December 2020 with three women from the village, namely the head of the Women’s Farmers Group (Kelompok Wanita Tani, KWT), a member of the Empowerment of Family Welfare (Pemberdayaan Kesejahteraan Keluarga, PKK), and a fisherwoman, as well as prominent men in the village.

To explain the roles of women and men in peatland management in the village, I rely on the Harvard Analytical Framework (HAF) developed by the Harvard Institute for International Development in the USA in collaboration with the US Agency for International Development (USAID) Office of Women in Development in 1985. Also known as the Gender Roles Framework, the HAF provides a matrix for data collection at community and household levels and is comprised of three main tools, namely a “socio-economic activity profile” (identifying productive and reproductive tasks by asking “Who does what?”), an “access and control profile” of participants, and other “influencing factors” (March et al. 1999, p. 32). I used the HAF to better understand the basic features and differences of the gender roles and the specific needs of men and women in the village to help determine how to best ensure the optimal contribution of all community members to peatland management and restoration. In designing the survey for this research, I simplified the HAF and created three activity profiles for men and women, namely productive (socioeconomic), reproductive (household), and sociopolitical activities.

7.3 Findings and Discussion

7.3.1 Peatland Knowledge of Men and Women

Three questions in the survey assessed community member’s knowledge of peatlands. First, men and women were asked if they could identify the differences between peatland soils (tanah gambut) and mineral soils (tanah mineral, or yellow soil). Mineral soils in Rantau Baru Village are more suitable for agricultural activities than peat soils. Peat soils consist of vegetative material that has decomposed over the past thousand years and are always partially submerged in water (BRG 2019b, p. 13). Residential areas of Rantau Baru are usually close to mineral soils, where residents grow vegetables in small quantities for self-consumption, as mass cultivation is difficult in this flood-prone area. Villagers were asked, “Are you able to differentiate between peatland soil and mineral soil?” (Question 16). In Fig. 7.2, we see the response results, that 92% of men and 78% of women could differentiate the two types of soil.

Men and women were then asked about the source of their knowledge about peatland cultivation. The results are depicted in Fig. 7.3. Both men and women learned to cultivate peatland mainly from previous generations (63% of men and 62% of women). The primary difference between men and women is in knowledge gained from the government and “other sources” (a 10% difference for each, with more men gaining knowledge from government and other sources than women). Also notable is that no men reported learning about peatland from their wives, but 13% of women reported gaining such knowledge from their husbands. Interestingly, no men or women reported gaining knowledge from nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). This data does not indicate a difference between men and women in the level of knowledge of peatland cultivation.Footnote 4

Finally, men and women were asked about their participation in training and socialization activities about peatland management. The results, as shown in Fig. 7.4, show that while nearly 90% of women have never participated in such activities, 76% of men have never done so. Therefore, as of the time of the survey, more men in the Rantau Baru village had participated in peatland management training and socialization than women. The frequency of such participation is extremely low for both men and women, with only 11% of men having participated in training and socialization more than once in a span of 2 years; only 5% of women had attended with the same frequency. This gender gap remains more or less consistent across frequencies. This data points to an urgent need for more training and socialization about peatland management focusing on women in the village.

7.3.2 The Roles of Men and Women

By modifying the categories of the Harvard Analytical Framework, this section presents a profile of men and women’s productive, reproductive, and sociopolitical activities in Rantau Baru Village.

7.3.2.1 Productive Activities: Peatland Cultivation and Fishing

The importance of gender issues in forestry and fisheries is inevitable, as these activities are not gender-neutral (FAO 2016). Gender-based segregation in forestry and fisheries is evident in the distribution of work between women and men, the invisibility of women’s contributions, and women’s limited access and control in decision-making. Although scholars note these tendencies and promote gender perspectives, many studies and policies in these sectors are gender blind (Colfer et al. 2016). Indeed, an World Bank et al. (2009) study notes that the role of women in the both the formal and informal forestry sectors has not been fully recognized or documented. In Indonesia, employment in the forestry sector is still dominated by men, and activities such as training, meetings, and campaigns are still directed at men and exclude women (Engelhardt and Rahmina 2011). Scholars agree that gender integration in forestry faces several obstacles and the sector lacks gender awareness (Mai et al. 2011, pp. 246–248). The following section explores role of men and women in peatland management, which is part of forestry and farming activities.

This section examines the different roles of men and women in the productive activities of Rantau Baru Village, an agricultural and fishery-based community. Villagers mainly use peatland for oil palm plantations, but they also cultivate chile, sweet potatoes, pineapple, banana, coconut, mango, guava, and rubber on peatland. Work related to the productive utilization of peatland in the village consists of: clearing the peatland for cultivation, fertilizing, harvesting, and selling the agricultural products. Table 7.1 depicts the participation of men and women in each of these activities according to survey respondents.

A majority of respondents (64%) reported that land preparation activities, namely clearing the peatland, are performed jointly by men and women. Half of the respondents also reported that fertilizing of the peatland was jointly done by men and women. Role differentiation was most striking in the activity of harvesting the fruit from the oil palms, with 81% of respondents reporting that this is done only by men, demonstrating the prominent role of men in this activity. A majority of respondents (64%) also noted that harvesting was done only by men. From these percentages, it can be said that although women participate in productive activities in peatlands by jointly clearing and fertilizing peatlands with men, men play a more predominant role, especially in harvesting and selling.

Programs to include or improve women’s contribution to peatland management in the village are also lacking. According to Erna, the head of the Women’s Farmers Group (Kelompok Wanita Tani, KWT) of Rantau Baru and a member of PKK Rantau Baru, monthly PKK meetings held before the pandemic discussed related topics, such as the environment, children’s health, healthy food, and clean water. A women’s training program to learn things like baking or making plates from pandan leaves or palm sticks was also conducted, but the majority of the women in that program quit and not many continued to use those skills (interview with head of KWT, November 23, 2020). Erna explained that in the previous 6 years, she had attended three musrenbangdes, or village development plan deliberation, where PKK is the only women’s representative group, and not all PKK officers were invited. Interestingly, Erna has never discussed KWT’s various problems in PKK or musrenbangdes, as PKK mainly discusses PKK’s performance (interview with head of KWT, November 23, 2020). There are no meetings or trainings specific to agricultural activity, or a program for peatland restoration, for women in Rantau Baru.

A gender perspective can be promoted to ensure the participation of women in peatland restoration and management. For example, the Indonesia Climate Change Trust Fund (ICCTF) ICCTF implemented a program to reduce emissions in Indonesia through local activities, including in Dumai, Riau, which involved a special program for women to participate in peatland management through the creation of women’s groups. The women’s groups have been involved in peatland management by planting red ginger through agroforestry and fish farming through biofloc ponds, which have become productive activities not only to improve organizational skills, but also to increase economic value (Wagey 2018, p. 2). This example shows real action to improve women’s contribution to and participation in peatland management in Riau.

In the fishery sector, the FAO (2016, p. 1) notes that ‘women’s engagement in fisheries can be viewed from social, political and technical perspectives, all of which show that the role of women is often underestimated.” The FAO (2016, p. 3) further notes that “almost universally, women play key roles in the fishery industry and household livelihoods and nutrition. These women, estimated at approximately 90 million, are often invisible to policymakers who have traditionally assumed – mistakenly – that fisheries are largely a male domain.” This inadequate recognition of women’s contributions in fisheries hampers the development process.

As explained in Chap. 5, fishery production in Rantau Baru increases during the rainy season, which lasts 3–4 months. Work in the village’s fishery sector consists of catching fish in rivers/lakes, processing fish by salting and smoking, and selling fresh fish and processed fish. Many of the fish caught in Rantau Baru are not sold fresh, for example, baung, patin, and gabus. These are processed in the village (see Fig. 7.5) and can fetch higher prices than fresh fish. This fish processing depends on the season, with only a few fisherfolk preparing salted fish in the dry season, which lasts from March to August, and many preparing smoked and salted fish during the rainy season, when the catch is abundant (BRG 2019b, p. 62).

Table 7.2 depicts the participation of men and women in the fisheries activities of Rantau Baru. While a slim majority of survey respondents (51%), report that catching fish in rivers and lakes is done by both men and women, nearly half of respondents (48%) note that processing the fish (salting and smoking) is done exclusively by women. Only four respondents reported that only men process fish, with the remainder of respondents (47%) reporting that both men and women process fish. Women also play a large role in selling fish, with 45% of respondents reporting that both men and women sell fish and 37% reporting that only women sell fish.

According to the results of this study, women in Rantau Baru participate in and contribute to the fisheries sector, particularly in the processing (salting and baking) of the fish. Overall, the sector has a more egalitarian gender role distribution pattern compared to peatland cultivation activities. Nearly half of respondents said that catching fish is done jointly done by men and women; women in the village play a major role in processing the fish; and a majority of respondents report that selling fish is done by both men and women.

The case of Ana, a 49 year-old Meliling fisherwoman from Sepunjung sub-village (Dusun 1), provides a sketch of daily life. After her husband became sick in 2004, every morning and evening Ana has used a sampan (traditional boat) and “net catches” (jaring yang ditinggalkan) to catch fish in the Kampar River. She then salts or smokes her catch (usually baung or salai) and brings the fish to the Kerinci Market every Sunday. In 2004 she could sell around 10 kg of salted fish per week at a price of Rp15,000 per kg, but in 2020 she was only able to catch and sell 4 kg of salted fish per week at a price of Rp20,000 per kg. She says that since 2017, the number of fish has been rapidly declining due to the increasing number of fisherwomen who use more advanced technology to catch fish. Ana is a member of a men’s fisher group that fisherwomen are allowed to join. The group can write proposals to request funding support from the District of Pangkalan Kerinci, but there is no funding or support from the Rantau Baru Village Fund or from the District of Pangkalan Kerinci for fisher groups (interview with Ana, fisherwoman, December 10, 2020).

How can we understand the above data in the broader framework of gender and fisheries? Here, efforts by international agencies can be useful. Examples include the FAO’s Sustainable Fisheries Livelihoods Programme (SFLP), as a holistic approach to gender analysis and the incorporation of local gender action planning through a bottom-up approach to advocating policy to support and empower women (FAO 2016, p. 8) and Weeratunge-Starkloff and Pant’s (2011) collaboration with diverse women and men farmers and fishers, government agencies, and research institutions to create innovative research-based policies and interventions to close the gender gap in fisheries. The FAO ( 2007, p. 1) notes that in the small-scale fisheries sector, development policies have traditionally targeted women as fish processors, and fishery-related development activities have engaged men as exploiting, and sometimes managing, resources, whereas women have been excluded from planning “mainstream” fishery activities. The Rantau Baru fisheries sector aligns with Ogden (2017, p. 117), who notes that “although there are global patterns of women mainly gleaning and men mainly engaged in capture fisheries, researchers are revealing that women’s involvement in fisheries dynamic and diverse over space and time.”

Despite women’s involvement in the productive activities of peatland cultivation and fisheries, gender analysis is often missing from development projects. In their evaluation of how gender was considered in 20 livelihood development projects implemented in coastal communities in Indonesia since 1998, Stacey et al. (2019) found that: (i) despite many projects reaching women, particularly with efforts to increase women’s productive capacity through training and group-based livelihoods enterprises, 40% of the projects had no discernible gender approach, and (ii) only two of the 20 projects (10%) applied a gender transformative approach that sought to challenge local gender norms and gender relations and empower women beneficiaries, suggesting the need for greater understanding of the role of gender in reducing poverty and increasing well-being. Stacey et al. (2019) provides further evidence of the importance of gender equality and women’s empowerment in small-scale fisheries and associated livelihood improvement programs.

The findings of this study offers new insights into the different roles of men and women in peatland cultivation and fisheries activity, which can hopefully contribute to a better understanding of the gender dimension of these sectors and a subsequent improvement in programs.

7.3.3 Reproductive Activities

Reproductive activities (in both agricultural and fishery-based families) mainly occur inside the household and commonly refer to domestic activities, as opposed to activities in the public sphere. The domestic activities (of which there are many) chosen for this study are childcare and managing household finances. A majority of respondents (61%) reported that childcare is performed by both men and women, while 39% reported that only women perform childcare. This finding indicates relative gender equality in the households of Rantau Baru Village when it comes to the activity of childcare, although the degree to which both men and women participate in this activity was not elaborated. When it comes to deciding how to use household funds, 59% of respondents reported that women alone manage household finances, and 34% report that finances are jointly managed by men and women. Only 7% reported that household finances are managed exclusively by men. This finding indicates that women in the village play a dominant role in family money management (Table 7.3).

To better understand the reproductive activities of fishery families in the village, I interviewed Santi, a Malay Datuk Tuo fisherwoman who is also the head of working group 3 (kelompok kerja, Pokja) PKK Rantau Baru 2020–2023. Santi said that she does all the same household activities as ordinary housewives (washing, cooking, and cleaning), but her fisherman husband never helps with these duties due to being busy. Santi said that both she and her husband both take care of child-rearing and manage the household money (interview with Santi, December 23, 2020). Similarly, the fisherwoman Ana said that her husband is willing to help wash dishes, but he does not wash clothes, except in the washing machine. Ana said that she and her husband always discuss various problems at home, including the allocation of money for their two daughters studying at university. Notably, Ana always tells her daughters not to be fisherwomen, but that it is acceptable to pursue a career in agriculture (interview with Ana, December 10, 2020). Rosa (19 years old), secretary of PKK Rantau Baru, also said that those in her generation no longer want to be fisherwomen or work in agriculture due to natural disasters and regular flooding (interview with Rosa, secretary of PKK Rantau Baru, December 10, 2020). In general, we can observe a trend of declining interest among younger generations in both fishing and farming. However, this does not necessarily mean that the role of women in productive activities will decrease, because women (especially young women) can still work outside these sectors and outside the village, for example as factory workers, and contribute to the productive activities of the family in this way.

The management of household finances by men and women in Rantau Baru was further examined according to ethnicity. By cross-referencing the ethnic identity of the respondents, we can differentiate the responses of Malay and non-Malay (namely Javanese, Batak, Minangkabau, and Nias) respondents. The differentiation between Malay (Melayu) and non-Malay (non-Melayu) is noted by Simulie (2002, p. 13) in which Malay including Deli Malay (Melayu Deli) and Riau Malay (Melayu Riau), in contrast to other ethnicities, such as Javanese, Sundanese, Bugis, Minangkabau. The results, presented in Table 7.4, reveal that a similar percentage of Malay (58%) and non-Malay (65%) respondents report that the wife in the family manages the household’s finances. This indicates that generally, both Malay and non-Malay families have similar experiences: the wife is primarily in charge of money management in the family, while the husband has the supporting role. A slightly higher percentage of Malay families (36%) say that both husband and wife control money in the family, while only 29% of non-Malay families say the same. From these results we can conclude that (1) generally, women play a significant role in money management in Malay and non-Malay families, (2) the higher number of Malay families jointly managing the household’s money may indicate more gender-equal relations in these families.

7.3.4 Sociopolitical Activities

Sociopolitical activities in Rantau Baru include attending village, neighborhood association, and community association meetings. The participation of men and women in these activities is depicted in Table 7.5. The majority of respondents (64%) report that only men attend these public meetings, while 32% report that both men and women attend, and only 4% report that only women attend such meetings. This result indicates that women’s participation in sociopolitical activity in the village lags behind that of the men. This is a significant finding because important decision-making related to women’s needs takes place at such meetings.Footnote 5

This finding could be explained by the matrilineage system of the Malay Petalangan community of Rantau Baru, in which although authority within a lineage or sub-lineage is in the hands of a mamak (a chief) or a kepala suku, (a prominent respected man), women gain high respect by possessing land or an inheritance, including a Sialang tree. In this system, women have less authority in the public sphere, where the mother’s brother (ninik mamak or mamak) and prominent respected men in the lineage represent the family’s voices and needs in public meetings.

Another indicator of sociopolitical activity is participation in women’s groups. There are two women’s groups in Rantai Baru Village, namely the PKK and the Women’s Farmers Group (Kelompok Wanita Tani, KWT). Although Rantau Baru is a village dominated by fishing, there is no women’s group related to fisheries. There are only men’s fishery groups that fisherwomen are allowed to join (see the example of Ana who is a member of such a group as explained in Sect. 3.2.1 above).

The PKK has five main organizers (pengurus) and 23 members in Rantau Baru village; the village also has one Posyandu (integrated service for children) with three main organizers (BRG 2019b, p. 51). The religious group Wirid Yasin for women has approximately 25 members, while Wirid Yasin for men has 23 members (BRG 2019b, p. 52). As seen in Fig. 7.6, of the 76 female survey respondents, 47 have never attended a PKK meeting. The small numbers of women who attend PKK meetings more frequently indicates that only PKK committee members take an active role.

According to Rosa (secretary of PKK Rantau Baru), PKK management consists of one leader (the wife of the PKK village head), four vice-leaders, two secretaries, and two treasurers, which were elected by a musyawarah (collective decision) attended by approximately 40 women from three sub-villages in Rantau Baru. Some of these attendees are from the KWT. The PKK receives funds from the Village fund (dana desa) of Rantau Baru (see Chap. 8 in this book). During the last musrenbangdes meeting that Rosa she attended, there was no discussion about the village’s strategy for peatland restoration, although other institutions (private companies) have given it much attention and offered help in various ways, such as sharing pineapple seeds to be planted. There has so far not been any PKK meeting on peatland restoration (interview with Rosa, December 10, 2020).

My interview with Ibu Santi, the Malay Datuk Tuo head of Pokja 3 PKK Rantau Baru for the period 2020–2023, revealed that Pokja has approximately 20 women members, whose regular meeting is conducted once every 3 months. Pokja programs include greening (penghijauan) and planting herbs (such as cabe, jahe, kunyit, kencur, daun kunyit) by optimizing the land around the houses, and they encourage households in each neighborhood association (Rukun Tetangga, RT) to plant herbs around their houses for their own consumption. They plant in tanah mineral, or mineral soil, because they have no experience planting in peatland. Pokja 3 has never had a program to train their members to cultivate vegetables in peatland. According to Santi, no training is offered by Pangkalan Kerinci District; district officers only encourage villagers to cultivate herbs in mineral soil, not yet in peatland soil, and Pokja 3 and KWT have never worked together (interview with Santi, December 23, 2020).

Erna further explained that although she was also a member of PKK, the initial development of KWT did not involve PKK, because the PKK officers would not come to Dusun Seipebadaran, which is located rather far from the PKK officers’ houses inside the village (interviews with Erna, September 1, 2019 and November 23, 2020). As the village head’s wife generally leads PKK organizations, they generally have good access to resource support from the village government. The PKK organizations tend to be centralized and biased toward the interests of the village elite and the center of village administration.

Only five women respondents have ever attended a KWT meeting, with only 3 women attending once a week. In an interview with Erna, the head of KWT Rantau Baru, she explained that Agricultural Trainees (penyuluh pertanian) from the Agricultural Bureau of Pelalawan District created KWT in 2016 and she has been its head since then. While KWT was initially made up of 30 women, this number shrank to only five to ten women due to differing ideas among them, the challenges of cultivating in the peatlands, and exasperation with the floods, which often destroyed the KWT demonstration plots of chilies, long beans, and eggplant (interviews with Erna, September 1, 2019 and November 23, 2020).

Erna and her parents are originally from Rantau Baru (they called it daerah bawah), but they moved to Seipebadaran in 2013 and gradually learned to cultivate crops in peatlands, which often face failure. They moved to Seipebadaran because their former location often became flooded, which distressed their life, and her school-age son needed a more stable condition.

Some of KWT’s initial program involved creating sustainable food houses (pembentukan rumah pangan lestari), such as chile nurseries, and creating demplots for chile and eggplant, for which they received assistance from the Agricultural Bureau of Pelalawan District, including seeds, equipment, and fertilizer in 2013; although, they no longer receive assistance. According to Erna, when the crops they plant are successful, they share them among the five women who are still active in KWT for family consumption and not for sale. Big floods are an ongoing challenge for KWT’s planting. For example, of their efforts to cultivate chiles, long beans, eggplant, and kale (kangkung), only kale was successfully harvested, as the rest were flooded (interview with Erna November 23, 2020). The types of vegetables planted by Erna and her KWT friends are not very different from those grown on peatlands in Central Kalimantan (including mustard greens, kale, and cucumbers) and on peatlands in other areas, such as chilies, tomatoes, celery, leeks, long beans, corn, pineapple, and bananas (Harsono 2012, p. 31).

Erna explained that KWT members practice different planting techniques than those taught by Agricultural Trainee Officers, as the technique taught by the officers was not suitable for the surrounding peatlands. The women proceeded with their own method: They combined mineral soil (tanah mineral, bought from Pelalawan) and natural fertilizer (pupuk kompos), placed this mixture in the center of the plot, planted vegetable seeds (Chinese cabbage, chilies, peanuts, corn, eggplant, long beans) there, and surrounded this planted area with peatland soil. This technique was successful for growing mustard greens in the demplot, but in 2015, a big flood swept away the plants just before harvest. This exasperated the KWT members, who no longer wanted to do group gardening (interview with Erna, September 1, 2019).

During observation in 2019, Erna and four other members of KWT were planting peanuts (see Fig. 7.7). As peanut cultivation is simple, they do not need fertilizer, and they can be harvested within 3 months. The demplot, as well as the KWT members’ individual initiatives to grow vegetables (chilies, peanuts, pumpkins) around their houses in polybags, are helpful in fulfilling their family’s food needs. They often do not need to buy vegetables, especially chilies, when the prices are very expensive. As KWT only received assistance from Pelalawan District in 2013 and 2016, Erna and the other four women in KWT run the farm––buy the seeds and manage the land––through gotong-royong (collective effort). She has encouraged women in Dusun Bawah to create a farming demplot like the one she made in Dusun Atas (Seipebadaran) (interviews with Erna, September 1, 2019 and November 23, 2020).

The farming technique used by Erna and her KWT friends on the peatlands is efficient and cheap. When the chili plants are exhausted, they can be replaced with other plants using the remaining mineral soil and disposing of the used peat soil. Additionally, seeds from previously harvested chilis can be planted for a following crop. Erna learned this this cultivation technique in a training on chile cultivation provided by Riau Province in 2017 and training on how to cultivate peatland by the BRG in Siak in 2018. Erna said that more training is needed for KWT members to learn more about the types of peatland in Rantau Baru, such as wet peatland (gambut basah) and dry peatland (gambut kering), and how to cultivate in the conditions of each type, as well as how to improve the economic conditions of their families by, for example, selling crafts (interviews with Erna, September 1 and November 23, 2020).

When studying gender and natural resources management, it is important to capture and present the voices, needs, and rights of women, which are often neglected in natural resource management policies and programs (Dewi et al. 2020). By listening to the voices of women farmers in Rantau Baru, this study discovered the potential of Women’s Farmers Groups, such as KWT. Such groups apply local knowledge that is different from the techniques taught by agricultural officers and contribute to family food supplies. However, the study found that women in the village do not yet participate optimally in KWT. Therefore, more effort is needed to encourage women to participate in KWT and in socio political activities.

In addition, there is limited support for KWT from the village network, as no allocation from the village fund is used to support the activities of women farmers. The findings of this study indicate the need to provide more spaces for women farmers in the village to express, practice, and accommodate their locally based peatland management including via attending the village, neighbourhood association, or community association meetings. The local knowledge of women farmers in peatland cultivation is critical not only to ensuring full community participation in peatland management, but also represents a potential resilience that should be supported amidst the regular flooding of the Kampar River and the deforestation surrounding the village.

7.4 Conclusion

Based on observation, a household survey, and interviews in Rantau Baru Village, this study has four main findings. First, men were significantly more knowledgeable of peatlands than women. This was explained by the fact that the number of men who had participated in training or meetings for peatland conservation was higher than that of women, although there is initially no gender differentiation in family’s socialization (for men and women) on peatland. This gender difference in peatland knowledge was not observed in Herawati et al. (2019) and therefore contributes a new insight.

Second, while men and women both contribute to “productive activities” in the village, either as farmers (by cultivating peatland) or fishers, peatland agricultural activities are dominated by men. According to the survey results, much of the peatland clearing, harvesting, and selling of peatland crops is done only by men and only a small percentage of women, demonstrating that men in the village play a more considerable role in peatland agricultural activity. This finding is consistent with Herawati et al. (2019), which also found that agricultural activity in peatland communities are dominated by men. However, this study finds that in the fishery sector, gender roles are more evenly distributed, with both women and men participating in the activities of fishing, processing, and selling and women dominating the activity of processing fish.

Third, women and men play complementary roles in “reproductive activities” of the household, namely childcare, while women have significant control over household finances. This latter finding may be explained by the matrilineal culture of many villagers, which places women in a position of high respect.

Fourth, in contrast to the above finding, women do not participate nearly as much as men in the public sphere of “sociopolitical activities,” such as attending community, association, and village meetings. However, some women do belong to women’s groups and some women farmers have developed their own techniques to produce food on peatlands based on local knowledge.

This chapter echoes Elmhirst and Resurreccion (2008, p. 5), who assert that “experiences of the environment are differentiated by gender,” and thus “men and women hold gender-differentiated interests in natural resource management through their distinctive roles, responsibilities, and knowledge.” Although men currently play the dominant role in peatland management in Rantau Baru Village, as part of the Peat Care Village Program, women have the potential to contribute to the restoration of peatland, especially through women’s farmers groups, such as KWT. Any project or program on peatland restoration in Rantau Baru Village should recognize the basic features and differences of the gender roles and the specific needs of men and women in the village to ensure the optimal contribution of all community members to peatland management and restoration.

Notes

- 1.

Herawati et al. (2019, p. 854) does not analyze the possible influence of ethnicity on gender roles; instead, it provides only a general picture of the main ethnic groups of Riau Province, with the indigenous Malay making up 33% of the population, Javanese, 30%, Batak, 13%, and Minang, 12%.

- 2.

The other provinces targeted by the BRG for peatland restoration are: Jambi, Kalimantan Barat, Kalimantan Tengah, Kalimantan Selatan, Riau, Sumatera Selatan, and Papua.

- 3.

The BRG’s 2019 Riau Province Yearly Action Plan is comprised of six KHGs, namely (1) Bengkalis Island, (2) Rangsang Island, (3) Indragiri River–River Cenaku, (4) Kiyap River–Kerumutan River, (5) Nilo River–Napuh River, (6) Rokan River–Kubu River (BRG 2018, p. 1).

- 4.

- 5.

This finding contradicts Herawati et al. (2019)’s study of gender roles in peat-based communities in Riau Province, which found that both men and women contribute equally to the social life of the community and that women’s participation and membership in groups is equal to men’s.

References

BRG (Badan Restorasi Gambut) (2018) Lembar pengesehan rencana tindakan tahunan restorasi gambut Provinsi Riau tahun 2019. BRG, Jakarta

BRG (2019a) Laporan tahunan restorasi gambut. BRG, Jakarta

BRG (2019b) Profil desa peduli gambut: Desa Rantau Baru Kecamatan Pangkalan Kerinci Kabupaten Pelalawan Provinsi Riau. BRG, Riau

Colfer CJP, Basnett BS, Elias M (eds) (2016) Gender and forests: climate change, tenure, value chains and emerging issues. Routledge, Oxon; New York

Dewi KH, Raharjo SNI, Desmiwati et al (2020) Roles and voices of farmers in the “special purpose” forest area in Indonesia: strengthening gender responsive policy. Asian J Women's Stud 26(4):444–465. https://doi.org/10.1080/12259276.2020.1844972

Elmhirst R (1998) Reconciling feminist theory and gendered resource management in Indonesia. Area 30(3):225–235. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4762.1998.tb00067.x

Elmhirst R, Resurreccion BP (2008) Gender, environment and natural resource management: new dimensions, new debates. In: Resurreccion BP, Elmhirst R (eds) Gender and natural resource management: livelihoods, mobility and interventions. Earthscan, London; Sterling, pp 3–20

Elmhirst R, Siscawati M, Basnett BS et al (2017) Gender and generation in engagements with oil palm in East Kalimantan, Indonesia: insights from feminist political ecology. J Peasant Stud 44(6):1135–1157. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2017.1337002

Engelhardt E, Rahmina (2011) Development of a gender concept for the forests and climate change programme (FORCLIME) in Indonesia. GIZ and FORCLIME, Jakarta

FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations) (2007) Gender policies for responsible fisheries: policies to support gender equity and livelihoods in small-scale fisheries. New directions in fisheries: a series of policy briefs on development issues, no 6. FAO, Rome. http://www.sflp.org/briefs/eng/policybriefs.html. Accessed 2 Apr 2021

FAO (2016) Promoting gender equality and women’s empowerment in fisheries and aquaculture. FAO, Rome

Firth R (1946) Malay fishermen: their peasant economy. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner and Co., London

Harsono SS (2012) Mitigasi dan adaptasi kondisi lahan gambut di Indonesia dengan sistem pertanian berkelanjutan. Wacana Edn 27:11–37

Herawati T, Rohadi D, Rahmat M et al (2019) An exploration of gender equity in household: a case from a peatland-based community in Riau, Indonesia. Biodiversitas 20(3):853–861. https://doi.org/10.13057/biodiv/d200332

Indirastuti C (2020) Perempuan bertarung dengan api di lahan gambut: pengalaman perempuan desa di Provinsi Kalimantan Tengah dan Riau. J Perempuan 25(1):13–24

Mai YH, Mwangi E, Wan M (2011) Gender analysis in forestry research: looking back and thinking ahead. Int For Rev 13(2):245–258. https://doi.org/10.1505/146554811797406589

March C, Smyth I, Mukhopadhyay M (1999) A guide to gender-analysis frameworks. Oxfam GB, Oxford

Mizuno K, Fujita MS, Kawai S (eds) (2016) Catastrophe and regeneration in Indonesia’s peatlands: ecology, economy and society, Kyoto CSEAS series on Asian Studies, vol 15. NUS Press; Kyoto University Press, Singapore; Kyoto

Mugniesyah SSM, Mizuno K (2007) Access to land in Sundanese community: a case study of upland peasant households in Kemang village, West Java, Indonesia. Southeast Asian Stud 44(4):519–544. https://doi.org/10.20495/tak.44.4_519

Muslim, Kurniawan S (2008) Fakta Hutan dan Kebakaran Riau 2002–2007: informasi atas perubahan hutan gambut/rawa gambut Riau, Sumatra – Indonesia. Jikalahari, Riau

Ogden LE (2017) Fisherwomen: the uncounted dimension in fisheries management. BioScience 67(2):111–117. https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biw165

Resurreccion BP (2008) Gender, legitimacy and patronage-driven participation: fisheries management in the Tonle Sap Great Lake, Cambodia. In: Resurreccion BP, Elmhirst R (eds) Gender and natural resource management: livelihoods, mobility and interventions. Earthscan, London; Sterling, pp 151–173

Safitri MA (2020) Membumikan ekofeminisme dalam restorasi gambut: kebijakan, aksi, dan tantangan. J Perempuan 25(1):1–12

Sajogyo P (1983) Peranan wanita dalam perkembangan masyarakat desa. Rajawali, Jakarta

Simulie HKRP (2002) Melayu dan Minangkabau bagaikan dua sisi mata uang. In: Bakry SY, Kasih MS (eds) Menelusuri jejak Melayu-Minangkabau. Yayasan Citra Budaya Indonesia, Padang

Stacey N, Gibson E, Loneragan NR et al (2019) Enhancing coastal livelihoods in Indonesia: an evaluation of recent initiatives on gender, women and sustainable livelihoods in small-scale fisheries. Marit Stud 18:359–371. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40152-019-00142-5

Subono NI, Pratiwi AM, Boangmanalu AG (2020) Aksi perempuan fasilitator desa dalam revitalisasi ekonomi kelompok perempuan di desa gambut: atudi kasus 3 desa di Kalimantan Tengah. J Perempuan 25(1):47–61

Sumartomjon M (ed) (2019) Badan Restorasi Gambut mulai melibatkan kaum perempuan untuk jaga lahan gambut. Kontan.co.id, 14 Feb. https://nasional.kontan.co.id/news/badan-restorasi-gambut-mulai-melibatkan-kaum-perempuan-untuk-jaga-lahan-gambut. Accessed 1 Apr 2021

UN ESCAP (United Nations, Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific) (2017) Gender, the environment and sustainable development in Asia and the Pacific. United Nations Publication, Bangkok

Villamor GB, Desrianti F, Akiefnawati R et al (2014) Gender influences decisions to change land use practices in the tropical forest margins of Jambi, Indonesia. Mitig Adapt Strateg Glob Chang 19:733–755. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-013-9478-7

Villamor GB, Akiefnawati R, van Noordwijk M et al (2015) Land use change and shifts in gender roles in Central Sumatra, Indonesia. Int For Rev 17(S4):61–75. https://doi.org/10.1505/146554815816086444

Wagey T (2018) Pengarusutamaan gender dalam tata kelola sumber daya alam: inisiasi kelompok perempuan dalam pengelolaan lahan gambut. In: Catatan Perjalanan Media Visit ke Lokasi Program ICCTF - UKCCU 2018. ICCTF, Jakarta

Watson E (2006) Gender and natural resources management: improving research practice. NRSP Brief, Hemel Hempstead

Weeratunge-Starkloff N, Pant J (2011) Gender and aquaculture: sharing the benefits equitably. Issues Brief 2011–32. WorldFish Center, Penang, p 12

Widiarti A, Hiyama C (2007) Prospek pelibatan perempuan dalam rehabilitasi hutan. In: Indriatmoko Y, Yuliani EL, Tarigan Y et al (eds) Dari desa ke desa: dinamika gender dan pengelolaan kekayaan alam. CIFOR, Jakarta, pp 83–91

World Bank (2018) Closing the gender gap in natural resource management programs in Mexico. World Bank, Washington, DC

World Bank, FAO, IFAD (International Fund for Agricultural Development) (2009) Gender in agriculture: sourcebook. World Bank, Washington, DC

WWF (World Wildlife Fund) (2012) Natural resource management and the importance of gender. WWF Briefing, Washington DC

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Dewi, K.H. (2023). The Dimension of Gender in Peatland Management in Rantau Baru Village. In: Okamoto, M., Osawa, T., Prasetyawan, W., Binawan, A. (eds) Local Governance of Peatland Restoration in Riau, Indonesia. Global Environmental Studies. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-0902-5_7

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-0902-5_7

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-99-0901-8

Online ISBN: 978-981-99-0902-5

eBook Packages: Earth and Environmental ScienceEarth and Environmental Science (R0)