Abstract

Understanding return on investment is a common priority for evaluating schools that operate as hubs for their community. Seeking answers to questions like, ‘are we getting adequate returns on our investment?’ and ‘when and where do we need to invest resources to maximise returns?’ is paramount to ensuring the sustainability of school as community hubs (SaCH) because they require ongoing funding to achieve their purported benefits for students, families and residents in local school communities. Economic evaluation designs that enable investment in SaCH to be compared with tangible benefits as well as future cumulative benefits will be explained and compared in this chapter. The discussion will be supported with examples that include practical strategies from economic evaluations of SaCH conducted in Australia and internationally where Social Return on Investment, Cost Benefit Analysis and Value for Money designs have been adopted.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

Determining what is valuable, what counts as ‘good enough’, and what offers the greatest return when a school is acting as a community hub are fundamental considerations. The questions are important regardless of whether a school is or is not a community hub, but for the former they are necessarily more complicated to answer in an evaluation. As discussed in earlier chapters of this book, Evaluating Thinking and the Success of Schools as Community Hubs (Paproth et al., 2023), and An Evaluation Framework for Schools as Community Hubs (Clinton et al., 2023), schools that act as community hubs can have interactions with community-based services, local governments and organisations as well as individuals in the community who all may be using school facilities on or off-site. Each of these stakeholder groups could have a different view of what might be considered valuable, or what might be accepted as an adequate return on investment, further still their activities individually and as a collective will contribute differently to the functioning of the whole school and local community.

Taking these contextual considerations into account, this chapter explores the application of economic and evaluative reasoning to schools that act as community hubs, and offers practical strategies for school staff, policy makers and other stakeholders engaged in economic evaluations.

Economic Evaluation in an Education Context

While there are many different types of economic evaluation, their common thread is that they all involve some comparative analysis of courses of action, where both the costs and the consequence of each action is considered to arrive at a judgement of merit, worth and significance (Drummond et al., 2005; Scriven, 1991). Evaluation theorists who have developed common typologies of different evaluation approaches, tend to advocate that economic evaluation is conducted when the evaluand (subject of the evaluation) is stable (Owen, 2006).

In education contexts, economic evaluations can be used to judge the value of school-based programs and policies, for instance, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) regularly reviews the performance of education systems across OECD countries, to capture how this performance relates to future economic productivity in terms of workforce participation, and gross domestic product. For example, a recent report detailed the impact (in economic terms) of learning loss over periods of interrupted and remote learning over the 2020 school year due to global restrictions associated with Coronavirus-2019 (Hanushek & Woessmann, 2020).

As one type of evaluation, economic evaluation can help “…provide robust information about whether something is valuable enough to justify the resources used” (Kinnect Group & Foundation North, 2016, p. 69).

Types of Economic Analysis for Schools as Community Hubs

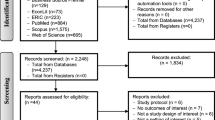

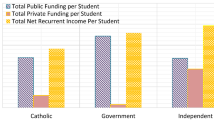

Table 1 presents five economic analysis methods, each with advantages and disadvantages for evaluating schools as community hubs. Of the listed analysis methods, social return on investment (SROI) and cost benefit analysis (CBA) offer advantages when it comes to assessing schools as community hubs, particularly in the ability to compare investments with multiple outputs (e.g., programs and activities) and a variety of outcomes that could change over time. It is therefore unsurprising that most published economic evaluations of schools as community hubs or community schools have been conducted using SROI and CBA (Bowden et al., 2020; Deloitte Access Economics, 2021; Watson et al., 2016).

A recent SROI of the National Community Hubs program in Australia found that for every $1.00 invested in resources associated with schools acting as community hubs in Australia, $2.20 in returns are generated in social benefits, including educational attainment, students’ future employment and health and wellbeing (Deloitte Access Economics, 2021). A CBA of City Connects in the US, a whole-school program offering comprehensive wrap-around support for students to receive all necessary services, yielded a very similar benefit to cost ratio, where $2.76 value is generated for every $1.00 invested (Bowden et al., 2020).

Cost-effectiveness (CEA), cost utility (CUA) and CBA along with SROI all aid in understanding the efficiency of investments made for schools to work as community hubs in different ways. They enable an evaluator to make a conclusion about relative value, comparing the return from different activities withing SaCH (CEA and CUA), and whether an investment creates more value than it costs to implement. For instance, SROI enables outcomes and costs to be combined and be expressed as a ratio or overall value generated. However, each of these options, in isolation, are not able to determine how ‘well’ resources are used and whether such resource use is justified in reference to social or distributive justice.

In the context of schools that act as community hubs, social or distributive justice is an important concept, as in some cases, schools acting as community hubs are seeking to redress imbalances in resource allocation and access to services and education (Jacobson, 2016; McShane & Coffey, 2022). Accordingly, an approach to economic evaluation that answers questions about the degree to which resources are being used well is needed for the economic evaluation of schools as community hubs.

Dr. Julian King built on the original concept of value for money (VFM, focussed on understanding good resource use) and developed the value for investment approach (VFI). VFI is an economic evaluation approach that combines evaluative reasoning with economic analysis (King, 2019) to enable those involved to think and act evaluatively (see Clinton et al., 2023). Specifically, VFI enables:

-

A theory of change to be tested,

-

Investments to be compared to outcomes, and

-

Interpreting the ratio of outcomes to benefits with relevant contextual information from both qualitative and quantitative sources.

Value for Money in Schools as Community Hubs

VFI builds on the traditional economic evaluation methods detailed in the previous section because it combines evaluative reasoning with economic theory and principles (King, 2017). The VFI approach is holistic and utilises a mixed methods approach, where multiple forms of evidence that are both qualitative and quantitative can be combined and included in the valuation process. Importantly the approach also encourages stakeholder engagement, with their input contributing to evaluation co-design, fact-finding, and informing the judgement of value for money.

Stakeholders’ views are incorporated most fundamentally in the development of criteria (and subsequently a rubric) for defining contextually determined criteria such as economy, efficiency, effectiveness, and equity in the context of the operations and outcomes of schools that act as community hubs. Figure 1 details and summarises the eight stages of the VFI approach to assessing value for money.

Stages of VFM methodology, i.e. the VFI approach (King, 2020)

Step 1: Understanding the Subject

The first step in the VFI approach is to generate a detailed understanding of the subject of the VFI, in this case the design and scope of the work of schools that act as community hubs. As noted in the Evaluation Framework for Schools as Community Hubs, this is also the first stage of building an evaluation framework. Often a logic model is used to define the investments, associated outputs and outcomes, or in other words the theory of change. In many cases, by the time an economic evaluation is occurring, a theory of change may have already been defined, however it is essential to ensure that any theory of change which is articulated in a logic model, reflects the reality of how a school is working as a community hub, therefore reviewing this is an important first step of the VFI approach. Depending on the stage of the SACH, it may be possible to extend the theory of change to be a theory of value creation, which details how a SACH can generate more value than the invested resources (King, 2021).

Step 2: Develop Criteria

Having established the theory of change for schools working as a community hub, it is then necessary to develop criteria of merit or worth. These entail performance descriptors (see box below), which tend to be broad but measurable statements that define success. Some organisations adopt the Four Es as a framework of criteria, such as but not limited to the UK National Audit Office, and the Australian Government (see the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act, 2013):

-

Economy: investments are of sufficient quality at an appropriate cost to produce desired outcomes,

-

Efficiency: Conversion of investments into outputs (e.g., facility use, school programs), including a school’s influence over the quality and quantity of outputs,

-

Effectiveness: delivery of outputs in a way that they achieve the desired outcomes, and

-

Equity: Outcomes and all benefits associated with the delivery of outputs must be distributed equitably.

There may be other dimensions (outside of the four E’s) that stakeholders or evaluators also wish to examine, which could be added if that is the case, but any descriptor must be able to be evidenced by the collection of data, whether this is qualitative or quantitative. For example, a fifth criterion called cost-effectiveness is often added to the framework, and this is often where economic methods such as those described in Table 1 can contribute to the VFI assessment.

Performance

A consistent definition of levels of performance is a goal to aim for, to the extent that this is possible. The following offers a guide to consider.

High performance: Schools working as community hubs are meeting the aims and objectives they seek to achieve. In some areas they may be achieving more than the stated aims, but there is also the possibility for continued growth.

Moderate performance: Schools working as community hubs are meeting aims in most areas, but some improvement is needed to increase and sustain performance.

Average performance: Schools working as community hubs are meeting minimum objectives, but not fully achieving the aims. Large improvements are required to progress.

Poor performance: Schools working as community hubs are not meeting minimum requirements, significant and major improvements are required.

For schools as community hubs that are regularly engaging in monitoring and evaluation, there may be information recorded about economy, and efficiency which could be used in an economic evaluation eliminating the need for new data to be gathered for those areas. Effectiveness and equity are likely to require analysis or regularly collected information. For example, if a school leader was interested in understanding whether student attendance had improved since investment into facility improvements was made at the school, they could access the school’s attendance data before and after the facilities had been improved to address this question.

Step 3: Develop Standards

The third step is to build on the performance descriptors and organise them into levels of performance. Often this is categorical, i.e., ‘high’, ‘medium’ or ‘low’, but there could also be existing standards for a component of schools as community hubs, for instance there may be existing standards for the efficiency of school facility design and use, these can be incorporated and where possible used as part of the VFI approach.

Whether standards are being developed, or existing standards are being adapted for use, each standard needs to relate to the four E’s and descriptors for each should be developed in step 2. Further each standard must also clearly define levels of performance within each descriptor. For example, standards for effectiveness must include a definition of ‘poor’ effectiveness, ‘good’ effectiveness and so on.

The methods associated with developing both criteria and standards, are not specific to VFI assessment; methods used to develop rubrics for assessing performance in an educational assessment, or evaluation are the same as what can be used to evaluate VFI. It is recommended that participatory processes be used, where stakeholders with direct involvement in the design, funding and implementation of schools working as community hubs are gathered to come to a shared understanding of what is necessary at each level of performance for each criterion. Steps 2 and 3 can be completed together, with a similar or ideally the same group of stakeholders.

Step 4: Identify Evidence Requirements and Methods to Gather Data

Once the criteria and standards have been developed, a plan for how to gather evidence to assess performance is required. Again, if VFI is embedded in a broader evaluation it is likely that this may already be in place. Identifying appropriate methods for gathering evidence is an important consideration in the context of the VFI. Put another way, step 4 needs to define the requirements also for this evidence. For example, to make a judgement about efficiency, it is likely that evidence about investments need to be provided at the ‘unit’ and ‘year’ level. That is, the cost of maintaining a school gym as a facility that is used outside of school hours needs to be separated from the cost of maintaining other school buildings. Further costs can change over time, due to market changes, inflation, and so recording actual funds in each year they are spent is necessary (Levin et al., 2017).

Step 5: Gather Evidence

The gathering evidence phase is like a data collection phase in any evaluation and will usually include an economic method as described in Table 1. Using existing monitoring and evaluation activities is ideal if credible evidence will be gathered that will enable the evaluator to assess the level of performance that a school working as a community hub is at relative to the criteria and standards developed in steps 2 and 3.

Step 6: Analyse Evidence and Step 7: Conduct Synthesis and Determine VFM Judgement

Analysis of evidence gathered usually requires three stages, particularly if both qualitative and quantitative evidence has been gathered. The first stage requires that each source of evidence to be analysed first individually at the data source level, to determine findings at the source level. The second stage (consistent with a mixed methods triangulation design, see Plano-Clark et al., 2008), involves identifying the degree of convergence (similarity in findings) and divergence (where findings are contradictory across sources) across the findings. This needs to be done firstly for each individual criterion (each of the 4 E’s), and then synthesised across all criteria. Finally, the third stage involves using the standards for each criterion where a judgement of the level of performance is made for the schools to work as a community hub across each criterion.

In practical terms, the process of arriving at this judgement may require additional stakeholder input, particularly if a determination as not been made a priori about whether criteria are weighted equally, for instance it may be important for effectiveness to be weighted more strongly than economy criteria.

Step 8: Reporting

Finally, the last step involves reporting the results of the VFM assessment adopting a VFI approach. This may vary depending on who the audience(s) are, and how the findings can be useful to those audiences relative to their specific role or stake in a school acting as a community hub.

One essential component of the reporting process is to clearly identify assumptions and parameters upon which the evaluation is based. Economic data is highly sensitive to contextual changes, which is ideal when considering reliability, however it can also mean that return on investment can be vastly different from one year to the next. For instance, if a school is engaging in facility redesign, it is possible that a very large investment is being made in one year, and within the same year little benefit is found because the facility is not yet ready for intended use, however in the second and third year, since the initial investment, benefits may far outweigh costs because building maintenance costs are low (particularly for a new buildings), and use is high.

In the context of schools working as community hubs, it may be advantageous for a VFI approach to be considered a living exercise, where investment data is being regularly updated along with outcome data to understand progress. For example, evaluations conducted early in the life of a school operating as a community hub might focus solely on economy and efficiency, later adding effectiveness and equity as outcomes data become available. However, completing the full process, particularly steps 6–8 is only advised when sufficient evidence is available, and it is timely for a judgement to be made based on the theory of change underpinning schools as community hubs. A premature judgement using a VFI approach is highly vulnerable to arriving at a conclusion about performance that is inaccurate, hence Owen’s recommendation for economic evaluation to be conducted when an evaluand is stable (2006). To that end, economic evaluation should be considered one element of thinking and acting evaluatively as part of sustaining effective SaCH and contributing to embedding the 12 key factors and six principles of the How to Hub Australia Framework (Cleveland et al., 2022).

Conclusion

Reflecting more broadly on VFI as an approach to economic evaluation, this chapter has highlighted that the steps of the VFI approach align with that of an overarching evaluation framework (see Clinton et al., 2023). Specifically, the use of routine monitoring data including budgets, the clarification of the theory of change (which can be used in other evaluation activities) and finally, the development of conclusions about whether resources invested have generated more benefit than they cost, plus whether the resource investment is justified are generated.

A VFI approach can overcome some of the criticisms of applying other economic evaluation methods in complex programs aiming to address wicked problems (see Paproth et al., 2023), because it enables the inclusion of multiple sources of evidence, and for evidence to be included in the comparison of costs and benefits that would not be appropriate to monetise (apply a financial value to reflect the worth of the benefits).

VFI is an interdisciplinary approach to economic evaluation, which supports the process of thinking evaluatively in the economic analysis process, which can help overcome the disadvantages of traditional economic analysis for use in evaluating schools that work as community hubs. It offers the generation of actionable conclusions about value which can be used to inform resource allocation and efficiency in the planning of SaCH. While economic evaluation is most often conducted in summative evaluations where longitudinal outcome data is available, assessing VFM in a formative evaluation enables conclusions to be used in SaCH planning and inform decision making around large investments in facility design, for example.

Economic evaluation is an important component of monitoring and evaluation activities in SaCH. We argue that a VFI approach to economic evaluation is the best-fit and can support more specific analysis approaches such as social return on investment and cost benefit analysis to be conducted when longitudinal outcome data is available. Generating evidence about the value of SaCH is essential for schools to continue to work as community hubs in a sustainable manner, by informing decisions about investing in activities, programs and services that maximise the value of school facilities and assets for the benefit of the school community as well as the local community.

References

Australian Government. (2013). Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 No. 123, 2013. https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2017C00269

Bowden, A. B., Shand, R., Levin, H. M., Muroga, A., & Wang, A. (2020). An economic evaluation of the costs and benefits of providing comprehensive supports to students in elementary school. Prevention Science, 21(8), 1126–1135.

Cleveland, B., Backhouse, S., Chandler, P., Colless, R., McShane, I, Clinton, J., Aston, R., Paproth, H., Polglase, R., Rivera-Yevenes, C., Miles, N., & Lipson-Smith, R. (2022). How to hub Australia framework. https://doi.org/10.26188/19100381.v6

Clinton, J. M., Aston, R., & Paproth, H. (2023). An evaluation framework for schools as community hubs. In B. Cleveland, S. Backhouse, P. Chandler, I. McShane, J. M. Clinton, & C. Newton (Eds.), Schools as community hubs. Springer Nature.

Deloitte Access Economics. (2021). National community hubs program: SROI evaluation report final. Prepared for Community Hubs Australia.

Drummond, M., Sculpher, M., Torrance, G., O’Brien, B., & Stoddart, G. (2005). Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. Oxford University Press.

Hanushek, E., & Woessmann, L. (2020). The economic impacts of learning losses. OECD Publishing.

Hyatt, A., Chung, H., Aston, R., Gough, K., & Krishnasamy, M. (2022). Social return on investment economic evaluation of supportive care for lung cancer patients in acute care settings in Australia. BMC Health Services Research, 22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-08800-x

Jacobson, R. (2016). Community schools: A place-based approach to education and neighborhood change. Economic Studies. https://healthequity.globalpolicysolutions.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/jacobson-final-layout-published-11-16-16.pdf

Kinnect Group, & Foundation North. (2016). Kua Ea Te Whakangao Māori & Pacific education initiative: Value for investment evaluation report. Foundation North.

King, J. (2017). Using economic methods evaluatively. American Journal of Evaluation, 1–13.

King, J. (2019). Evaluation and value for money: Development of an approach using explicit evaluative reasoning [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Melbourne.

King, J. (2021). Expanding theory-based evaluation: Incorporating value creation in a theory of change. Evaluation and Program Planning, 89, 101963.

King, J. K. (2020). Value for investment resources. https://www.julianking.co.nz/vfi/resources/

Levin, H. M., McEwan, P. J., Belfield, C., Bowden, A. B., & Shand, R. (2017). Economic evaluation in education: Cost-effectiveness and benefit-cost analysis. Sage.

McShane, I., & Coffey, B. (2022). Rethinking community hubs: Community facilities as critical infrastructure. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 54, 101149.

Owen, J. (2006). Program evaluation forms and approaches (3rd ed.). Allen & Unwin.

Paproth, H., Clinton, J. M., & Aston, R. (2023). The role of evaluative thinking in the success of schools as community hubs. In B. Cleveland, S. Backhouse, P. Chandler, I. McShane, J. M. Clinton, & C. Newton (Eds.), Schools as community hubs. Springer Nature.

Plano-Clark, V., Huddleston-Casas, C., Churchill, S., Green, D., & Garrett, A. (2008). Mixed methods approaches in family science research. Journal of Family Issues, 29(11), 1543–1566. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X08318251

Scriven, M. (1991). Evaluation thesaurus. SAGE.

Watson, K., Evans, J., Karvonen, A., & Whitley, T. (2016). Capturing the social value of buildings: The promise of social return on investment (SROI). Building and Environment, 103, 289–301.

Acknowledgements

This chapter is based on research conducted as part of the Building Connections: Schools as Community Hubs project, supported under the Australian Research Council’s Linkage Projects funding scheme (LP170101050).

The authors acknowledge Dr. Julian King for his Ph.D. research on the VFI approach, and for his review of this chapter. His work has informed the development of this chapter, and the application of the VFI approach in education.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Aston, R., Clinton, J.M., Paproth, H. (2023). Are Schools as Community Hubs Worth It?. In: Cleveland, B., Backhouse, S., Chandler, P., McShane, I., Clinton, J.M., Newton, C. (eds) Schools as Community Hubs. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-9972-7_22

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-9972-7_22

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-19-9971-0

Online ISBN: 978-981-19-9972-7

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)