Abstract

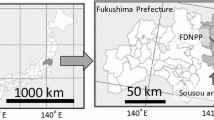

The disastrous accident at the Tokyo Electric Power Company’s Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant (FDNPP) in 2011 caused the release of significant amounts of radioactive waste, resulting in radiological (mainly radioactive cesium) contamination in the surrounding forests, agricultural fields, and residential areas.

To ensure the safety of agricultural products grown on farmland after decontamination, Fukushima Prefecture conducted monitoring inspections on about 233,000 samples (excluding rice, grass, and other plants) in around 500 products, and is continuing to do so while narrowing down the items to be inspected. More than 10 years after the accident, few items other than freshwater fish and forest products have exceeded the standard values. Since there are still concerns regarding radioactive contamination of agricultural products from Fukushima Prefecture, it is necessary to continue monitoring inspections and promote understanding of the products based on correct information in order to restore agriculture in the affected areas.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

2.1 Post-Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant Accident Safety Measures for Agricultural Products Produced in Fukushima Prefecture

Following the Great East Japan Earthquake on March 11, 2011, the accident at Tokyo Electric Power Company’s Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant resulted in the spread of contamination by radioactive materials (mainly radioactive cesium) over a wide area of eastern Japan, centered on Fukushima Prefecture. When the concentration of radioactive cesium in the soil (surface layer 15 cm) was 5000 Bq/kg or less, inversion tillage (deep plowing) was used, and when the concentration was more than that, topsoil stripping at a thickness of 5 cm or more was used. Decontamination work was completed in all areas except the difficult-to-return zone by the end of March 2017. Decontamination had been completed for approximately 22,000 housing sites, 8400 ha of farmland, 5800 ha of forests, and 1400 ha of roads. After decontamination, it is recommended that agricultural fields maintain a high exchangeable potassium content in the soil to prevent radioactive cesium absorption (the standard for rice cultivation is 25 mg/100 g or more), and potassium has been cultivated by adding potassium fertilizer to the usual potassium application. Furthermore, the epidermis of fruit trees was washed with water and peeled off to remove radioactive cesium.

To ensure the safety of agricultural products grown on farmland after decontamination, emergency environmental radiation monitoring (hereinafter referred to as “monitoring inspection”) based on the Act on Special Measures Concerning Nuclear Emergency Preparedness has been conducted since immediately after the accident. The inspection focuses on agricultural, forestry, and fishery items that are offered for sale in Fukushima Prefecture, and these products are inspected before being sent. Under the Food Sanitation Law, the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare set the interim regulating values for radioactive materials as 2000 Bq/kg for radioactive cesium and 500 Bq/kg for radioactive cesium on March 17, 2011. Furthermore, since April 2012, the standard value for the concentration of radioactive cesium in general foods has been set at 100 Bq/kg. If the concentration of radioactive cesium exceeds the standard value as a consequence of monitoring inspections, shipments are stopped by each municipality and will not be distributed to the market. During the 10 years following the accident until March 2021, Fukushima Prefecture conducted monitoring inspections on about 233,000 samples (excluding rice, grass, and other plants) in around 500 products, and is continuing to do so while narrowing down the items to be inspected (Fukushima Prefecture Monitoring of Agricultural, Forestry, Fishery and Processed Food Products Information HP 2021).

Rice is the most valuable agricultural commodity in Fukushima Prefecture and is the staple food of the Japanese people. Resultantly, in 2012, instead of a sampling inspection like the monitoring inspection, a more complete inspection of all rice produced in Fukushima Prefecture (estimated to be over 360,000 tons per year) was done [hence referred to as “inspection of all rice bags” (Fukushima No Megumi Safety Council HP 2021)]. A measuring equipment (generally known as a belt-conveyor type survey meter) was created to conduct the examination of all rice bags and determine if the concentration of radioactive cesium in a bag of rice (30 kg) is below the standard value in a few tens of seconds. Fukushima Prefecture installed approximately 200 belt-conveyor type survey meters and conducted inspections in conjunction with growers’ shipments. At the end of the inspection, an individual identification number is added to each bag of rice along with a sticker stating that it has been inspected, and the individual results can be viewed on the website.

2.2 Current Status of Agricultural Products from Fukushima Prefecture

Figure 2.1 shows the monitoring results of agricultural (crop, vegetables, fruit, etc.), livestock, forestry (wild vegetable and mushroom), and fishery (saltwater fish and freshwater fish) products from 2011, and the dotted line indicates the current standard value of 100 Bq/kg. In FY2011, immediately after the nuclear power plant accident, the percentages for grains (excluding rice), vegetables, and fruits were 7.2%, 4.7%, and 11.2%, respectively, but have declined dramatically after FY2012. Since FY2016, FY2013, and FY2018, respectively, no samples exceeding 100 Bq/kg have been detected in cereals (excluding rice), vegetables, and fruits. The high percentage of samples exceeding 100 Bq/kg in FY2011 was due to the direct fallout (direct contamination) of radioactive cesium emitted from the nuclear power plant on agricultural products (wheat, spinach, komatsuna, etc.) grown in the field. Furthermore, many of the few samples of produce that exceeded 100 Bq/kg since 2012 were found to be primarily due to the use of agricultural equipment contaminated by radioactive materials during cultivation, rather than absorption and transfer from soil to crop. Therefore, administrative guidance was also provided in Fukushima Prefecture to be very careful in the use of agricultural materials and machinery. Since 2012, roughly ten million rice bags (30 kg) have been inspected annually as part of a comprehensive inspection of all rice bags, separately from monitoring inspection. As a result, 71 bags of rice exceeding 100 Bq/kg were detected in 2011, 28 bags in 2012, and 2 bags in 2013, and no rice exceeding 100 Bq/kg has been detected since 2014. From 2020, all bags are no longer inspected using a belt-conveyor type survey meter, except for 12 of the 59 municipalities in Fukushima Prefecture that have been ordered to evacuate due to the nuclear power plant accident.

In FY2011, the percentage of meat that exceeded 100 Bq/kg in FY2011 was 0.8%. The reason why radioactive materials were detected in beef and pork was thought to be the feeding of feed contaminated with radioactive materials, so farmers were warned not to feed rice straw and grass that was outside at the time of the accident to their cattle and pigs, and administrative guidance was provided to prevent contamination of meat from spreading, and since FY2012, no radioactive materials have been detected.

For saltwater and freshwater fish, the percentages exceeding 100 Bq/kg were 24.5% and 30.8%, respectively, in FY2011, 12.7% and 12.9% in FY2012, 2.3% and 8.0% in FY2013, 0.6% and 2.8% in FY2014. Since FY2015, few saltwater fishes have been detected above 100 Bq/kg (one point exceeded 100 Bq/kg in January 2019), while 0.3% of samples of freshwater fishes were still above 100 Bq/kg in FY2019. Fishery products are also steadily declining, but some marine products (rivers and inland waters) continue to be detected. The reasons for this include contamination of food (fallen leaves and insects) and the fact that freshwater fish do not discharge much radioactive cesium that they have taken in in an attempt to maintain the salt concentration in their bodies.

The percentages exceeding 100 Bq/kg for wild vegetables and mushrooms were 35.5% and 19.4% in FY2011, 18.2% and 12.5% in FY2012, 11.6% and 4.5% in FY2013, 3.4% and 4.4% in FY2014, respectively. Since FY2015, mushrooms have not been detected above 100 Bq/kg, whereas wild vegetables were detected until FY2018. Differences were observed among wild vegetables, with a tendency for high concentrations in young leaf-eating wild vegetables such as Koshiabra (Eleutherococcus sciadophylloides). The concentration of radioactive cesium in wild vegetables and mushrooms has also decreased markedly over the years. However, the reason why they are higher than other items is because the mountains where they grow are undecontaminated and potash fertilizer is not applied to suppress the absorption of radioactive cesium.

2.3 Future Prospects

Some farmers in Fukushima Prefecture were unable to farm due to the evacuation zone or were apprehensive about selling their produce, and the utilization rate of arable land fell dramatically following the nuclear power plant accident (FY2011: National average 92%, Fukushima prefecture 75%). Ten years have passed since the nuclear accident, and evacuation orders have been lifted in many areas, but the arable land utilization rate in FY2018 is still at the same level as it was immediately after the nuclear accident (Fukushima Prefecture 2021). One of the factors behind the lack of a return to arable land use is that the rate of return has not increased even after the evacuation order has been lifted. The reasons why the return rate has not increased is that, in addition to the fact that people have established their lives in the evacuation sites after the nuclear accident, life in the satoyama, where people live in communities close to forest, has also disintegrated. Many of the areas where evacuation orders were issued are surrounded by mountains, and for people living in the mountainous areas, growing rice in the paddies at home and gathering wild vegetables and mushrooms in the neighborhood were part of their daily life. Even after decontamination is complete and rice can be grown in the paddies, some people are hesitant to return to their homes, because their enjoyment will be cut in half if they cannot eat wild vegetables and mushrooms. Although the economic evaluation of collecting wild vegetables and mushrooms for personal consumption may be low, it is a significant concern for the locals, and the restoration of satoyama life is one of the issues that will be addressed in the future.

Furthermore, while few samples exceeding the standard values have been detected in monitoring inspections, but there are still concerns regarding radioactive contamination of agricultural products from Fukushima Prefecture. Furthermore, unlike before the nuclear accident, rice produced in the areas near the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant (Hamadori and Nakadori) is increasingly employed for commercial purposes, and the price of rice has remained low. To dispel such rumors, the results of monitoring inspections have been publicized, and aggressive marketing activities have been conducted in the Tokyo metropolitan area.

Regarding cultivation, potassium fertilization, which has been implemented as a measure to control the absorption of radioactive cesium, is gradually being phased out. However, considering the half-life of radioactive cesium, it will take a long time for all cesium in the agricultural environment to disappear; therefore, regular monitoring is required to maintain safety. The livestock industry in Fukushima Prefecture is also thriving, but because grass and other feed containing high potassium content can cause grass tetany in cattle, it is not possible to rely solely on potassium-enriched fertilizers, and the prefecture is struggling with countermeasures. Research on rice types that are less likely to absorb cesium has made progress (Nieves-Cordones et al. 2017; Rai et al. 2017), which is expected to revitalize agriculture, and it is hoped that this will be applied to pasture grasses as well.

Fukushima Prefecture is Japan’s third largest prefecture in terms of geographical area, and its agriculture, forestry, and fisheries industries are rich in regional characteristics, ranging from regions with mild winters and long hours of sunshine to inland regions with large daily temperature differences. The prefecture is rich in natural resources and is a leading producer of rice and other agricultural products such as cucumbers, tomatoes, pea pods, Asparagus, and peaches. Fukushima Prefecture’s agricultural product value decreased greatly after the nuclear accident (2011: 185.1 billion yen) compared to prenuclear accident (2010: 233 billion yen) but rebounded to 208.9 billion yen in 2019 (Fig. 2.2). In the evacuation zone, specific reconstruction and revitalization centers have been established, and efforts to regenerate agriculture have begun, albeit gradually. Although some areas have aged rapidly due to the nuclear accident, farmers in Fukushima Prefecture are struggling to engage in agriculture in new ways, such as opening vineyards with wine breweries, forming sweet potato and flower production areas, improving efficiency through smart agriculture, and exporting agricultural products from Fukushima Prefecture. Farmers are concerned about the loss of production on soil that has lost its crop layer, as well as whether their products can be marketed. Continued monitoring inspections and promoting understanding of produce based on correct information are necessary for agricultural recovery in the affected areas.

References

Fukushima No Megumi Safety Council HP (2021). https://fukumegu.org/ok/contentsV2/

Fukushima Prefecture (2021) Current status of agriculture, forestry and fisheries in Fukushima Prefecture. https://www.pref.fukushima.lg.jp/sec/36005b/norinkikaku2.html

Fukushima Prefecture Monitoring of Agricultural, Forestry, Fishery and Processed Food Products Information HP (2021). https://www.new-fukushima.jp

Nieves-Cordones M, Mohamed S, Tanoi K, Kobayashi NI, Takagi K, Vernet A, Very A (2017) Production of low-Cs+ rice plants by inactivation of the K+ transporter OsHAK1 with the CRISPR-Cas system. Plant J 92(1):43–56

Rai H, Yokoyama S, Satoh-Nagasawa N, Furukawa J, Nomi T, Ito Y, Hattori H (2017) Cesium uptake by rice roots largely depends upon a single gene, HAK1, which encodes a potassium transporter. Plant Cell Physiol 58(9):1486–1493

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Nihei, N. (2023). Recovery of Food Production from Radioactive Contamination Caused by the Fukushima Nuclear Accident. In: Nakanishi, T.M., Tanoi, K. (eds) Agricultural Implications of Fukushima Nuclear Accident (IV). Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-9361-9_2

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-9361-9_2

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-19-9360-2

Online ISBN: 978-981-19-9361-9

eBook Packages: Earth and Environmental ScienceEarth and Environmental Science (R0)