Abstract

The Dream of the Red Chamber, an 18th-century epic about the fall of a noble family that is considered one of the “four great classical novels” of Chinese literature, became available to Dutch readers only three centuries later, when its first full translation was published in November 2021. It took the trio of Silvia Marijnissen, Mark Leenhouts and Anne Sytske Keijser 13 years to translate the 120 chapters. Their final version runs into four volumes totaling 2,160 pages.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

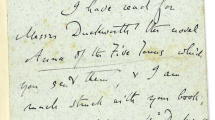

Anne Sytske Keijser is a Dutch translator known in China by her Chinese name Geshu Xisi. She is a lecturer in modern and traditional Chinese and Chinese literature at the School of Chinese Studies at Leiden University, the Netherlands, which is also her alma mater. In addition, she studied at Xiamen University in southeastern China. She has translated Chinese classical literature as well as authors such as essayist Zhou Zuoren, Lu Xun’s younger brother, Chinese-American novelist and poet Hualing Nieh Engle and novelist Su Tong, author of the acclaimed novella Raise the Red Lantern that was made into an iconic film.

Anne Sytske Keijser

The Dream of the Red Chamber, an 18th-century epic about the fall of a noble family that is considered one of the “four great classical novels” of Chinese literature, became available to Dutch readers only three centuries later, when its first full translation was published in November 2021.

It took the trio of Silvia Marijnissen, Mark Leenhouts and Anne Sytske Keijser 13 years to translate the 120 chapters. Their final version runs into four volumes totaling 2,160 pages.

The Dutch version caught the eye of Dutch scholars and media and was reviewed by several publications. Keijser talks about the epic labor the translation required and its significance in introducing Dutch readers to Chinese culture, especially the young generations.

CNS: People are curious why it took 13 years to complete the translation. What was the most challenging part during the work? And what was the most interesting?

Anne Sytske Keijser: Actually, we didn’t work on the translation full-time for 13 years as we all have our own jobs. I teach at Leiden University and Silvia Marijnissen and Mark Leenhouts were translating other things besides the Dream of the Red Chamber.

Still, it took so long because first of all, we had to find a way to translate its tone appropriately into Dutch. The Dream of the Red Chamber contains a lot of very interesting and engaging dialogue with very subtle details, from which you can understand the characters’ personalities. So sometimes even after we had translated the lines faithfully, it would feel like something was missing. They were not vivid enough or lifelike enough because the tone had not been conveyed accurately.

For example, take the Chinese word nin (“您,” “you” in English, used to address someone of an elevated status). In Dutch, we have a similar word but it conveys only respect, not the difference in status. In the Dream of the Red Chamber, the tone of nin changes a lot. You would think that Xiren (the maid of Jia Baoyu, the protagonist of the novel) would address Baoyu as nin but due to her close relationship with him, she never calls him that. On the other hand, she uses nin to address Wang Xifeng (the wife of Baoyu’s cousin). Those details distinguish the relationships between the characters and we have to pay attention to them to convey the nuances.

Translating the Dream of the Red Chamber also required substantial understanding of the cultural background. It exposed us to various aspects of traditional Chinese culture, which was particularly rewarding. For example, where the book mentions Chinese medicine, we had to read up Chinese medicine to find out what the herbs it mentioned were and why Baoyu said certain medicines should not be taken by girls but boys. When we translated the parts related to the Grand View Garden (the sprawling garden in the novel that provides the setting for much of the plot) we learned a lot of interesting things about Chinese architecture. Subsequently, when we visited a Chinese garden near Groningen (a city in northern Netherlands) with our new-found knowledge, we found the garden design fascinating.

In addition, the Dream of the Red Chamber includes certain things that have no equivalent in Dutch, so we had to invent phrases when we translated them. For example, there is no Dutch word for kang (“炕,” a raised platform made of brick, mud or stone with a stove-like heating system inside which served as a traditional bed), so there was no way to translate it. We felt we should keep the original word. So we made an annotation the first time it appears in the book, and subsequently, used kang in the rest of the text.

For the characters of the novel, the names of the aristocrats have been transliterated into Dutch, while the names of the servants have been translated according to their meaning. Xiren was one of the most difficult names to translate. It took us three years to work that out as it had to be a beautiful Dutch name. We would translate it and one of us would think it was okay but the others would not and then we would try again. Only when all three of us agreed finally, we decided on the name.

CNS: After the full translation was published, a review called the Dream of the Red Chamber “a literary masterpiece of both beauty and depth.” In China, we have something called “Redology,” that is, academic study, research and comment on the Dream of the Red Chamber. However, you and your co-translators have repeatedly said that the target reader for the Dutch edition is the general public. How did you balance depth with making the book comprehensible to the general reader?

Anne Sytske Keijser: That’s a good question. We gave this issue a lot of thought before we finally decided to make a compromise. For example, there are many names in the book, so we added a list of the characters and their relationships at the end of each volume, so that the readers can turn to it when reading the book to understand who’s who.

As this edition is for the general reader, we decided not to add too many annotations, although the translation would lose some meaning. In the case of names which have many meanings, we added footnotes explaining them. Interestingly, when you read the Dream of the Red Chamber, you are so immersed in its world that you would be less concerned with the meaning of the names, jumping straight into the next chapter to find out what happens next.

The poetry in the book also has a wealth of meaning and literary allusions. If there’s one line by Li Bai or Du Fu (two great poets in ancient China), we can add a footnote. But if it’s a poem of 10 or 12 lines, we can’t add five annotations for just one line as it would affect the flow of the narrative.

Dutch readers have a different background from Chinese readers. The Dream of the Red Chamber is a Chinese classic, many Chinese have known it since they were children and have watched the TV series adapted from it. However, there is no such background for the Dutch readers. So the first step is to turn the story into Dutch and make it readable; then organize events, such as lectures, to explore the depth of this masterpiece.

CNS: It’s been some time now since the Dutch edition came out. What do the readers say?

Anne Sytske Keijser: Honestly, I am surprised. The reviews have been better than expected. The readers have liked it very much. The first print run sold out, and the publisher is ordering a reprint.

For Dutch readers, reading the Dream of the Red Chamber is like entering an entirely new world. As it is set in a very traditional feudal society in 18th-century China, they may find everything strange at the beginning and not quite understand why the characters behave the way they do, but usually, after the first 100 or 150 pages, they will be completely absorbed in the world that this story creates and become so fascinated by the characters that they won’t be able to stop reading till they come to the end.

Some readers left messages on my Twitter account, telling me that they had just finished reading the book and were now officially “saying goodbye” to it. The director of the public library in North Brabant (a southern province in the Netherlands) has a special fondness for the book and plans to organize a series of events to give readers an insight into its background. Some readers who had read the Dutch translation of Zhuangzi (a Chinese philosophical classic) before reading the Dream of the Red Chamber associated it with some of the details in Zhuangzi. This is rather interesting. They read Zhuangzi first and then the Dream of the Red Chamber, so it appears that they know the traditional Chinese culture.

CNS: As a literary masterpiece, the Dream of the Red Chamber is considered a window to Chinese culture. How can the Dutch translation help to acquaint the Dutch with Chinese culture, especially the young people?

Anne Sytske Keijser: It will help in many ways. Most Dutch don’t know much about traditional Chinese culture, but the Dream of the Red Chamber will resonate with them. For example, the girl who lives in the Grand View Garden knows that her good life will end soon because she will get married. She doesn’t know what will happen after that, she might be miserable. This feeling of being confused and anxious about the unpredictable future is something that young people may particularly empathize with.

Another example is the struggles of Baoyu, whose family had great expectations of him. I remember when I first read the Dream of the Red Chamber in my early 20 s, I felt particularly empathetic toward him when I thought of the pressures of life and the feeling of not being able to handle the future. Then, of course, there are the romantic episodes and you wish that the young pair could be together. But for various reasons, they fail to become a couple, and readers realize the complexity of the storyline.

After starting to translate the Dream of the Red Chamber, I offered a course on its social background at the School of Chinese Studies. Some students were interested in the relationship between the Dream of the Red Chamber and Buddhism and Taoism, some analyzed Wang Xifeng’s position in the Rongguo Mansion (where Baoyu lived) and some studied the status of women in the book. Some who were double-majoring in law discussed the laws of the society that the story was set in.

Also, the daily life in the Dream of the Red Chamber is depicted in a very realistic way and Dutch readers can learn about the life of the Chinese aristocracy back then through the descriptions in the book. After reading the novel, one reader thought it was “unbelievable” that some characters in the book felt lonely since they were always surrounded by a lot of servants every day. This is a perspective that had never occurred to me.

CNS: From an academic perspective, what role does your translation play in the Dutch translation circles and in Sinology?

Anne Sytske Keijser: I think a major contribution of this translation is that it justifies the translatability of masterpieces like the Dream of the Red Chamber. Some Dutch translators think that “certain books just cannot be translated” and there were voices that the Dream of the Red Chamber was untranslatable.

The three of us discussed whether the translation should be done by only one person, and we agreed that one person might collapse since it was so complex; two or three people working together would be fine, while four would be too many. The three of us, we all have our own strengths: Marijnissen is good at translating poetry, Leenhouts has translated challenging works of literature such as Fortress Besieged (a 20th-century Chinese satirical novel), and my specialty is traditional Chinese culture and Chinese history studies and I also know about classical Chinese writing. So the three of us started to work together. Now that the full translation of the Dream of the Red Chamber is done, there are many other great works of Chinese and world literature to be translated, so we will keep working hard.

From a literary point of view, the full Dutch translation can also play a role in promoting the diversity of world literature. After reading the Dream of the Red Chamber, Dutch readers may be interested in other Chinese literary works and want to read them. There is also the TV series and if it is available in the Netherlands, I believe many people will watch it and then read the book.

Overall, I think it is very worthwhile to learn about another culture and another world through literature. In my lectures, I often say that many students may not like Chinese literature, just like many Dutch students are not fond of Dutch literature either. I hope that my course can in some way invoke their curiosity about Chinese literature or even inspire them to work as translators or in the diplomatic service or in cultural institutions in the future, doing something to promote cultural exchange and communication between the Chinese and Western cultures.

(Interviewed by De Yongjian)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this license to share adapted material derived from this chapter or parts of it.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 Dolphin Books Co., Ltd.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Keijser, A.S. (2023). Why the Dutch Translation of the Dream of the Red Chamber Took 13 Years. In: Chen, L., Pohl, KH. (eds) East-West Dialogue. Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-8057-2_45

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-8057-2_45

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-19-8056-5

Online ISBN: 978-981-19-8057-2

eBook Packages: Literature, Cultural and Media StudiesLiterature, Cultural and Media Studies (R0)