Abstract

This chapter examines how a particular social event, Malaysia’s 2021 budget is reported in The Star Online. It aims to analyse the discourse surrounding the budget through use of corpus-assisted discourse studies (CADS). Using corpus linguistic techniques, a specialised corpus is firstly compiled of the phrase ‘Budget 2021’ in The Star Online from one month before and after Parliament passed the budget on 26 November 2020. A total of 889 articles ranging from a number of sections (e.g. Nation, Letters, and Business) were identified from the website that resulted in 339,651 words. Standard corpus methods were employed namely, the investigation of frequency lists, collocational patterns as well as examining the corpus in more detail via concordance. Findings from the Budget 2021 corpus show patterns of how language is used to describe, explain as well as oppose a political issue like the national budget, which may influence how governance achieves legitimacy in the eyes of the public. It also reveals how discursive meanings can be viewed in a more systematic way.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

11.1 Political Discourse of Digital Texts

Investigating ‘discourse’ is usually discussed in terms of the structural point of view of institutions and power within a particular social context. As Nordquist notes:

[d]iscourse studies look at the form and function of language in conversation beyond its small grammatical pieces such as phonemes and morphemes. This field of study, which Dutch linguist Teun van Dijk is largely responsible for developing, is interested in how larger units of language—including lexemes, syntax, and context—contribute meaning to conversations (27August 2020).

Within the specific political context of a discourse, there are mainly two types as described by Ädel (2010): the first is to focus on the political genre as the main criterion—by ‘political discourse’ here, any forms of communication or speech event, which takes place in a political context, and/or involving political agents. Other definitions of what ‘political discourse’ may mean could either be viewed from a broader scope (referring to any discourse on a topic which is political) or from an extended scope; the idea that power and control are (often or always) enacted through discourse, which makes it possible to consider any discourse as ‘political’. In the present chapter, we shall use the latter view, investigating how a political topic is discussed in an online social setting as a form of analysing ‘political discourse’ using corpus techniques. More specifically, the chapter sets out to investigate how talk about Malaysia’s 2021 Budget in a selected online news portal can be carried out via a corpus approach, revealing discursive tendencies that shape the forms of journalism. In addition, findings from this chapter emphasises on instances of (de)legitimation as a result of intertextual features in the news.

As Ädel further points out, “[p]olitical discourse is frequently represented in corpora, in part because many political genres are not only public but also widely publicised, which makes them more easily accessible than many other types of discourse” (2020, p. 592). Echoing from this, digital texts that demonstrate political discourse are therefore rich in meaning as readers now transition to obtaining news and information online. Although digital texts comprise a vast repository of different genres and text-type, the present chapter focuses on online written texts or articles systematically chosen (via the corpus linguistic approach) for political discourse in context.

11.2 Online News and Corpus Discourse Studies

Many academics have written about the democratising impact of digital media practises regarding news reporting and journalism. Hartley (2008) argues that the convergence of digital media and news contributes to a community of citizen journalists (McNair, 2006; Terry, 2009). This is attributed to the growth in user-generated content that decentralises and distributes the ability of netizens to produce content on their own (Bruns, 2008). This participatory media society creates an atmosphere in which media producers and users are increasingly interested in engaging with each other, where consumers are becoming increasingly stronger in relation to media producers (Jenkins, 2006). This provides people a more collective voice; the Internet has now broadened the conventional limits of debate, whilst also offering a range of resources for immersive, asynchronous, and multi-directional modes of discussion that could lead to more comprehensive dialogue on public concerns (Zamith & Lewis, 2014).

McNair (2006) suggests that since the advent of digital media and the Internet, journalism has seen a rise in democracy and transparency in the public sphere. This is mainly because opportunities to produce and distribute media have become more accessible to a wider range of people and in turn, this puts more critical scrutiny of political elites and the way governance is presented. Dahlgren and Sparks (2005) also assert the positive contribution of the Internet in facilitating democratic discourse and civic culture to the public that promotes civic engagement and interaction (Papacharissi, 2008). The result of this is the break-up of a singular, integrated public sphere into multiple, heterogeneous communicative forums and practises (Terry, 2009).

Online discourse is not only seen as a platform for democratising the way in which news were reported but is also felt like a means to express feelings or responses to everyday scenarios in the country. Apart from the accessibility, writers are said to contribute to the multiple viewpoints found in the readership, where both writer/readers views and voices are incorporated into the journalistic work (Collins & Nerlich, 2015). News reporting can be seen from different angles, either through the lens of the professional or the citizen journalist, and this new form of journalism encourages or stimulates for more “conversations” rather than receiving information from a single authoritative source (Collins & Nerlich, 2015).

One way to investigate political discourse is through corpus-assisted discourse studies, also known as CADS. This, according to Partington (2018: p. 2) is “a field of study in its own right” as more discourse studies have incorporated the use of corpora over the years (Partington et al., 2013: p. 10). Unsurprisingly so, studies that adopt CADS are often productive in that they are never exclusive nor intended to replace other approaches but “frequently marry well with, provide sustenance to, blend into and lead out of other types of approaches, and ways of collecting data […], which is why CADS is both particularly interdisciplinary and can be adopted in and adapted to so many other fields of study” (Partington, 2018: p. 2). He further argues that research using corpus linguistics and CADS “decontextualises in order to recontextualise and reconstruct the object of study, the discourse type under investigation” (2018: p. 4), which allows researchers to analyse language use at different levels of abstraction via machine interventions (e.g. corpus linguistic techniques and tools) that support the overall intuitive process.

Discourse as defined by Partington (2018) is “language in use as a vehicle of communication, as language doing things, as speakers and writers attempting to influence the beliefs and actions of their interlocutors using language” (p. 2) and some well-known corpus-based or CADS type of studies include the representations of Islam in the British media (Baker et al., 2013), the portrait of immigrants in the British and Italian press (Taylor, 2014), and media reporting surrounding the London Olympics 2012 (Jaworska, 2016). Typically, these studies begin with a quantitative analysis of a statistical output of some sort, followed by a close reading of concordance lines to investigate contextualised language use in more detail. As noted in Jaworska (2016: p. 9), “The CADS approach utilises the quantitative tools offered by corpus linguistics, but it extends the methodological paradigm by integrating techniques commonly associated with qualitative discourse analysis in order to understand the discourse in question and its context as much as possible”. In addition, comparison is often made between texts within two separate time frames (usually before and after a particular event) so as to evaluate the impact of certain events and how they are discursively constructed.

Whilst Rajandran (Chap. 3) and Farrah Diebaa and Su’ad (Chap. 4) study budget speeches, this chapter follows Perumal, Govaichelvan, Sinayah, Ramalingam, and Maruthai (Chap. 5) in studying media reporting of the 2021 Malaysian Budget. More specifically, it provides a snapshot of how The Star Online reports about the budget via an empirical (corpus linguistic techniques), and in-depth analysis, grounded in CADS.

11.3 The 2021 Malaysian Budget

The 2021 Malaysian national budget was tabled in Parliament on 6 November 2020. It was regarded as the largest budget in the country’s history with an increase of RM7.8 billion in expenditure (from RM314.7 billion in 2020 to RM322.5 billion in 2021). Named “Resilient as One, Together We Triumph”, the allocation of the budget was seen as contentious as it occurred during a global pandemic as well as a political crisis in the country (Tan, 2020a, 2020b).

At the time when the budget was tabled, Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin was facing political uncertainty as the Opposition leader Anwar Ibrahim claimed that he managed to garner enough support from parliamentarians to topple the Perikatan Nasional (PN) government. There was, therefore, a high political stake for the Finance Minister Tengku Zafrul Tengku Abdul Aziz to table a strong and effective budget that met everyone’s needs. Most importantly for the government, the budget should be able to get the support of the Members of Parliament (MPs), given the government’s slim parliamentary majority. To ensure that the MPs supported the budget, the Opposition bloc was consulted in the run-up to the budget presentation. The finance minister was reported to have made additional allocations based on feedback from both sides of the aisle, mostly with regard to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The main highlights of the budget included the increase of the COVID-19 fund allocation from RM20 billion to RM65 billion. The main purpose was to fund aid packages and benefits for frontliners as well as to procure vaccines (Tan & Yusuf, 2020). The second important measure of the 2021 Budget was to protect livelihood due to the loss of jobs as a result of the pandemic and underemployment. This included various approaches such as RM6.5 billion for a cash aid programme, RM28 billion for subsidies, aid and incentives, and RM1.5 billion to extend wage subsidy programmes. The budget also announced a targeted EPF Account 1 withdrawal facility of RM500 per month, up to RM6,000 for 12 months, with total withdrawal from EPF Account 1 amounting to RM4 billion (Ministry of Finance, n.d.). To sustain economic recovery, the 2021 Budget also provided relief for Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) grappling with survival and recovery during the pandemic. This included another set of allocation ranging from RM510 million to finance SMEs and micro-SMEs, RM800 million through capacity-building programme and RM95 million for special micro-credit fund to empower women entrepreneurs.

On 26 November 2020, Parliament declared that the 2021 Budget passed with a voice vote (Anand, 2020; Lee & Goh, 2020). Several refinements were made taking into account viewpoints from various parties. These include an increase of withdrawal limits of the Employees Provident Fund (EPF), an auto-approval mechanism for those in the B40 group as well as SMEs, rebranding of the government’s Special Affairs Department (JASA) to become the Community Communications Department (J-KOM) to justify the budget allocated at RM85.5 million and extending a one-off payment to frontliners battling COVID-19 (Yusuf, 2020; Palanasamy, 2020).

The 2021 Budget passed its third reading in the Lower House with a division vote on 15 December 2020 (The Edge Market, 2020). The ratification of the 2021 Budget was seen as a victory for Muhyiddin Yassin who returned with renewed doubts regarding his majority in the week preceding the final budget vote (Shukry, 2020). The Prime Minister, however, still faced strong opposition from Anwar Ibrahim who claimed to secure the backing of several government MPs from UMNO to undo Muhyiddin’s majority. His predecessor, Mahathir Mohamad, also announced that he was teaming up with a senior government MPs to form a government (Shukry, 2020), and this too seemed to create a sense of uneasiness. Amongst speculations surrounding the news were the rejection of the bill and involvement of a declaration of state emergency should Parliament not be able to reach a consensus. One of the reasons for this disagreement between parties can be traced to reporting on social media about proposals (mainly from the Opposition) that were not met and other criticisms of the budget, such as unrealistic projected earnings for 2021 and a dissolved BN department that was proposed to be given RM85 million (Ng, 2020).

Digital texts including online news that are publicly and widely publicised on the web provide a wealth of data for corpus linguists. More specifically, we aim to analyse talk about the Malaysian 2021 Budget in a popular national English online news portal, The Star Online. According to Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020, “[o]nline and social media remain the predominant sources of news for our online sample of Malaysian news users” (p. 98). The Star Online in particular was chosen because of its wide readability in the country. Using corpus linguistics techniques, a specialised corpus was firstly compiled of articles from The Star Online based on the topic (Budget 2021) as a search phrase. These include the various sections like Nation, Business News, and so on that also appeared as a result of the search between a specified timeline of when the bill was tabled and passed in Parliament.

11.4 Corpus-Assisted Discourse Studies (CADS)

This chapter incorporates corpus techniques in a study of Budget 2021 as a political topic. We follow Partington’s (2010) description of corpus study of political language that examines texts on political issues (like the budget), emanating from main sites of public experience of political issues, in our case, The Star Online. The study starts with a simple description of the list of words that may tell us how the topic of interest is talked about in the corpus. Whilst it may be argued that identification of keywords, i.e. words that are “statistically significantly more frequent” (Baker et al., 2013, p. 27) in one corpus than in another would be the typical starting point of a corpus study, in this chapter, it was not the intention to compare two corpora. Rather, it is possible to create a specialised corpus and investigate the use of language via online corpus analysis tools like Sketch Engine (Kilgarriff et al., 2014). Following this, further analysis is carried out using salient keywords identified as the starting point for qualitative analysis in CADS, as “corpus linguistics (CL) techniques provide a ‘map’ of the corpus, pinpointing areas of interest for a subsequent close analysis” (Baker et al. 2008, p. 284). In other words, by adopting the CADS approach, political discourse of online news surrounding the budget is investigated using corpus linguistic techniques to demonstrate how “[l]arge collections of tokens of a discourse type would seem to be a valid, appropriate, and rigorous way of reflecting the intertextuality of political discourses” (Partington, 2013, p. 4).

11.5 Corpus Building

As mentioned earlier, Budget 2021 was tabled in the Malaysian Parliament by the Finance Minister on 6 November 2020. Given this, it is useful to collect data four weeks prior to this event (6 October 2020) as well as another four weeks after the bill was tabled (6 December 2020) in order to potentially see differences in the way the budget was talked about leading up to the decision of passing the bill on 15 December 2020. The decision to compile a specialised corpus was found to be more suitable for this type of study as research has shown that there is equal wealth in examining smaller sized corpora for a more specific/focussed discourse (Flowerdew, 2004; Lee, 2008). A specialised corpus provides a snapshot of the language used to describe a particular occurrence in time and since findings have been sufficient for ample discussions, the duration for which the corpus was built was considered reasonable.

It should be noted that a full comparison of newspapers was not the aim of this study, for reasons of focus as much as space, instead we focussed on The Star Online as a popular and widely read mainstream online English newspaper in Malaysia, with 56% of online readers trusting the brand (Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, 2020). In this study, the specific search term ‘Budget 2021’ was keyed in on the website (www.thestar.com.my) that generated 889 related articles (ranging from those under sections like Nation, Letters, Business and so on) acting as a starting point in which the phrase was found. This amounted to 339,651 words to be analysed and in turn, enabled findings to be mostly specialised or discourse specific as to how Budget 2021 was described and discussed in The Star Online.

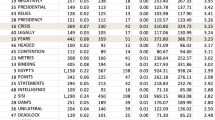

The first part of corpus analysis is quantitative in nature where statistical measures are used to determine salient words/phrases as the starting point of analysis whereas subsequent steps require qualitative analyses. This is a typical integration quality of CADS that “requires constant oscillation between quantitative and qualitative viewpoints, moving back and forth between computer-based discovery procedures and traditional, human hermeneutics” (Mautner, 2019, p. 8). Table 11.1 shows a list of frequent words found in the corpus. The statistical measure employed to determine the significance of difference is Average Reduced Frequency where ARF “is a variant on a frequency list that ‘discounts’ multiple occurrences of a word that occur close to each other, e.g. in the same document”, available on Sketch Engine (Kilgarriff et al., 2014). This enables us to consider the frequency of words in relation to the word’s distribution in the corpus that may otherwise be misleading on simple frequency of occurrence alone (Tranchese, 2019). In other words, this meant that the words are not only frequent, but they are distributed quite evenly across texts.

Table 11.1 compares the two different measures when counting for frequent words in a corpus (words in red are those not found in the corresponding frequency measure). For ease of readability, Table 11.1 shows first 30 and last 30 in the rank of 100 top frequent words according to absolute frequency and ARF.1 Since there is no cut-off point for using ARF and all words with an ARF score close to their absolute frequencies should be analysed, only the top 100 keywords (as identified in descending order by ARF scores) were considered following Tranchese (2019, p. 7).

These words were then categorised into semantic macro-categories, as shown in Table 11.2 that may identify the topics that dominated the discussion of Budget 2021 in the corpus using the free UCREL Semantic Analysis System (USAS) English semantic tagger available online. This web-based semantic tagger developed by Rayson (2002) is used to show semantic fields of words that are generated automatically online, which are then referenced following the USAS category system (Archer et al., 2002) to avoid risk of inconsistencies and bias. However, the list of semantically tagged words were manually inspected to ascertain more meaningful associations based on contextual information (for example, ‘will’ was labelled as a word depicting volition or relating to law and order by the software but is contextually grouped as showing effort/resolution in the case of ‘political will’). Other more generic terms (often grammatical) like ‘has/have’ were categorised under grammatical words. In short, despite the automatic tagging of top 100 frequently distributed words, they were also (partially) manually categorised to meet the context of the Budget 2021 corpus.

Grouping the wordlist (based on ARF measures) into semantic categories was the first step for analysis and it provided a sense of the context on how the budget was viewed in terms of dominant themes. Table 11.2 presents macro-categorisations of the top 100 words3 in the corpus, using the online free USAS semantic tagger. However, as mentioned earlier, certain words had to be reclassified upon realising the more suitable meaning that would be represented in the context of the corpus.

Upon first inspection, Table 11.2 shows that salient words in the corpus are mainly grouped as grammatical words and this is not unusual as most English texts display more functional words than lexical ones. Categories of ‘Movement, location, travel, and transport’ and ‘Numbers and measurement’ are equally striking in that despite their function as prepositions, suggest that the Budget 2021 corpus involves a lot of talk about quantities (e.g. some profit-taking activity, All MPs should support Budget 2021) and location/direction (e.g. exemption from July 1 to Dec 31 for this year, incentives under the campaign). This is not surprising as the articles collected were written during the time of tabling the budget and it could be argued that financial issues (depicted by words ‘budget’, ‘economy’ and ‘economic’ in the ‘Money and commerce in industry’ category), which are more topical were as noticeable as words describing senses that are measurable as well as in motion. Other initial findings from Table 11.2 point to the discussion around the COVID-19 pandemic, words related to the government or governmental activities (government, minister), spoken communication depicted by the reporting verb ‘said’, sense of volition (will) as well as words referring to obligation (need), help (support; help) and time (year; time).

These general semantic categories show that frequent words in the corpus were mainly from categories of ‘Movement’, ‘Numbers/Measurement’, followed by ‘Money’. These show that economic issues were prominent in the corpus as well as the description about them, signalled mostly by deictic markers, both temporal (e.g. out; in) and spatial (e.g. some; all) as well as prepositions like under. Whilst closed class words may not appear to show much, pronouns and proper nouns reveal interesting themes that may suggest the agentive role of certain people in the talk about Budget 2021 (e.g. we, Datuk, Malaysia). On the basis of this preliminary inspection of salient words in the corpus, it can be argued that recurring themes involving the health crisis, economy and the government are indeed part of what the budget was about. Although grouping salient words semantically may not show much definitive results, it was a helpful tool to highlight topics that were prominent in the corpus that can provide further insight into the next part of the research.

Since it would not have been possible to analyse all 100 top ranking words in the corpus, the key term ‘budget’ (ranked number 14 in the list) was used as our focal point in the next part of the study: collocation analysis. Through use of WordSketch, a tool available on SketchEngine, the word ‘budget’ was searched for its grammatical and collocational behaviour (i.e. collocates or co-occurring words) with a minimum frequency of five, using LogDice as the default statistic. This measure describes the typicality score indicating strength of association between the target/node word with its collocates—the higher the score, the stronger the collocation. Typical collocation of ‘budget’ is thus helpful to see how the word is used or referred to with other words in the corpus and then analysed in context through concordance analysis.

11.6 Collocation and Concordance Analysis

Having provided an overview of the main themes that characterised the Budget 2021 corpus, this section focuses on the collocation and concordance analysis of ‘budget’ more closely. Table 11.3 presents the most typical collocates of ‘budget’ using WordSketch. More specifically, the table shows how the budget is mostly referred to as a ‘budget deficit’. Although instances can also be found where the term ‘deficit budget’ was used, this only points to the same thing and therefore, adds to the number of how ‘budget’ typically occurs with ‘deficit’ (freq. = 24) in the corpus. As can be seen, ‘budget’ usually occurs as a subject (e.g. budget is; budget has), occurring with possessives (e.g. next year’s budget; facilitate the Government’s Budget; its budget); mostly collocating with verbs and adjectives (e.g. pass the budget; approve a partial budget; an expansionary budget; the national budget), as well as functioning as adjective (e.g. budget deficit; his maiden budget speech; 2021 Budget debate).

Generally, ‘budget deficit’ occurs when spending exceeds income. As Amadeo (2020) explains, deficit must be paid. If it is not, then it creates debt. This was found to be one of the concerns in the Budget 2021 corpus (lines 5, 13, and 22; see Fig. 11.1) and these may be argued as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic (lines 6, 10, 17, 20, and 21), where reports show “economic fallout [were] inflicted by the pandemic crisis” (Lee Heng Guie, 2020). This echoed the findings of the semantic grouping of frequently distributed words, indicating how the budget is described in relation to health and disease, particularly from the impact of COVID-19. The last two occurrences in Fig. 11.1 refer to descriptions of the budget deficit in other countries like Indonesia (lines 23 and 24), which may seem to normalise the idea of a budget deficit. This first look at the occurrences of ‘budget’ and ‘deficit’ demonstrates the first instance of intertextuality at play where information about the budget deficit is shared in detail across different sections of The Star Online, namely, Nation, Metro News, and Business News. Arguably a specific term within the business discourse, ‘budget’ and ‘deficit’ can also be seen in close proximity in Nation and Metro News, reporting how the budget creates an excess of allocation compared to an increase in debt as reported in Business News.

Next, most verbs patterning strongly with ‘budget’ as object had meanings associated with either approving it (e.g. pass, approve, support) or rejecting it (e.g. reject, oppose). This exemplification of two differing views offers the reader both positive and negative viewpoints of the budget in the corpus. Although the budget eventually was passed (supported by a majority vote in Parliament), it was found that there were speculations of whether the bill will “be defeated by the Opposition” and how the government was preparing for “possible scenarios”. Reasons for why this was the case was unfortunately missing from the reports. Other collocates that functioned as a verb with ‘budget’ as an object were described as neutral actions in relation to the process of debating, tabling, drafting, and presenting the budget (to name a few), whilst ‘defeat’ was found to occur with expressions of how the budget was “defeated” at the time, largely in part to the Opposition (see Fig. 11.2). This occurrence, mostly referring to the act of the Opposition curtailing the bill (depicted by the collocate ‘defeated’) was reported in the Nation sub-section. During this time, news about the possibility of the budget not being received in Parliament by a majority vote created a sense of spectacle over predictions of another general election (lines 7 and 8) and whether the Prime Minister should step down (lines 8, 10, and 11). Nation is one of the sub-sections of the newspaper that caters to local news and is updated throughout the day. By associating the budget with predictions of it being defeated, shows an example of delegitimising governance.

Concerns over the budget can also be seen in relation to the stock market index; Kuala Lumpur Composite Index (KLCI) that was found to have “retreated in early trade Thursday in line with the pause at regional markets, and ahead of the Budget 2021 vote in Parliament” (Murugiah, 2020). Figure 11.3 shows a screenshot of the local market overview for the year. As can be seen, three specific dates were marked as significant to the time of news reporting (in the corpus). The dip (circled in red) was identified during the time which the news reported on possibility of the budget being defeated (end of October 2020) and hence, could have triggered the stock market to ‘retreat’.

Another reason for the dip in the stock market was the mentioning of the King and his decision to declare a state of emergency, which was reported in proximity to the speculation of the budget to be defeated as shown in the examples below. As can be seen, these two separate reports show a similar style of reporting, which indicate forms of intertextuality as well as news being discursive.

PUTRAJAYA: It is back to preparing for Budget 2021 and finding more effective measures to combat COVID-19 for the government after the King decided against declaring a state of emergency for the country. Sources said the special Cabinet meeting had included, amongst other things, possible scenarios should the Budget be defeated by the Opposition. However, besides the special meeting – held for the second time in four days – other political meetings on the sidelines are equally sparking intrigue amongst observers (Nation, 27 Oct 2020).

Budget 2021 will see debates at the policy stage for almost two weeks and three days of ministerial replies, followed by voting by MPs on Nov 23 in Parliament. Previously, the government sought to declare a state of emergency after a special Cabinet had taken into account, amongst other things, possible scenarios, should the Budget be defeated by the Opposition. However, the King then decided against declaring a state of emergency, whilst reminding politicians to stop all forms of politicking that could disrupt the stability of the country amid the COVID-19 pandemic (Nation, 29 Oct 2020).

Nevertheless, the index rose on 15 December when news reported of a more optimistic view of the budget after it was passed in Parliament (Bernama, 2020). Another dip found before 15 December could be explained for in an article dated 14 December 2020 in Nation, where speculations of the budget to be defeated by a bloc vote was reported. However, since experts described the event as slim (Nation, 15 December 2020), the stock market rose again the following day.

Budget 2021, which is now in the second reading, was passed at policy stage. It is currently being debated at the committee stage. The budget has to be passed at the end of these debates on Tuesday where it could still be defeated by a bloc vote (Nation, 14 December 2020).

Close examination of the KLCI along with patterns from the concordance lines reveal a possible relationship between what was reported in the news as well as how this has potential impact on the stock market. Language choice on how the budget was argued for or against in the local news shows ways in which language patterns exhibit forms of (de)legitimising governance through use of intertextual features, arguably affecting economic activities like the stock market.

Other verbs related to ‘budget’ that may be of interest is how the bill was represented as a subject or having an agentive role. This is primarily seen where ‘budget’ occurs preceding the be-verb (is, are, was) and is discussed further here compared to occurrences of the phrasal ‘budget + has’ that were less frequent. Whilst most instances (68 out of 105 occurrences) showed ‘budget’ occurring with verbs that referred to the process of ratifying the bill (e.g. budget is rejected/passed/defeated), it was found that 37 other instances described the budget in terms of existential meanings (see Fig. 11.4). These include representations of the budget as being big/large and expansionary (lines 6, 11, 22, 33, 34, and 36). This resonates with other typical collocates that modified ‘budget’ in terms of size, i.e. an expansionary budget; the largest budget; and the biggest budget. This, as Cindy Yeap reports “is the biggest federal government budget announced to date in absolute (ringgit) terms, pipping even the outsized RM317.5 billion Budget 2019 that benefitted from a RM30 billion-special dividend from Petroliam Nasional Bhd (Petronas) used to return excess taxes to taxpayers” (The Edge Malaysia, 2020). At RM322.54 billion, or more than one-fifth of the economy, she further argues that the government may have to “raise its self-imposed statutory debt ceiling of 60% of GDP if it intends to borrow more money to spend on the people and bolster economic recovery” (The Edge Malaysia, 2020). In turn, this relates back to how Budget 2021 was typically discussed in terms of the budget deficit, pointing to more forms of intertextuality that demonstrate how political discourse in the newspaper is suggestive of ideologies, in this case, connecting the large amount of sum to an anticipated national debt.

11.7 Conclusion

Initial extraction of frequency lists with help from a sophisticated online corpus tool, SketchEngine has shown to be useful when directing us to important concepts in a text (in our case themes on financial issues, depicted by words ‘budget’, ‘economy’ and ‘economic’ as well as words describing senses that are measurable and in motion) that has helped to show how 2021 Budget was framed in The Star Online. More specifically, the corpus highlighted the concern for a massive budget deficit, possibility of the budget to be defeated, and descriptions of how the budget was ‘expansionary’. We could also argue for how ‘budget’ and ‘expansionary’ were reproduced to create an allusion as a form of legitimising governance; the frequent collocation alludes to the intention of an economic (or political) expansion at the expense of the actual amount involved. This shows identification of meaningful links between features of texts and the context in which they were produced (or received), highlighting that discourse and society are mutually constitutive in that meaning is a product of social practises (Mautner, 2019, p. 4).

Inarguably, “[c]orpora, being electronic collections of authentic texts, are a valuable source of first-hand language data for the empirically minded linguist” (Lew, 2009, p. 297). And as Baker (2004) notes on ‘discourse’, citing Parker and Burman (1993, 156), that “discourses emerge as much through our work of reading as from the text” and that “[b]ringing corpus linguistic methods on board is meant to put discourse studies on a sounder empirical footing” (Mautner, 2019: p. 8). This, we have found to bring methodological synergy in investigating political discourse in an online Malaysian news portal. More specifically, representations of Budget 2021 were explored via corpus techniques and CADS, which provided empirical evidence to strengthen traditional discourse analysis. Finally, this chapter recommends examining other forms of political discourse in sections of the same (or different) newspaper(s) that could reveal more about how Malaysia’s governance are reported.

Notes

-

1.

A number of words that seemed odd in the wordlist were those that came up as parts from the online newspaper sub-headings or tag lines like “Trending in Business”, “Stories You'll Enjoy”, “The Season Of Joy Is Here!”, “Check out our Christmas issue for ideas on gifting and ways to enjoy the festivities to the fullest”, which were discarded for further analysis.

-

2.

Where words are polysemous, they are given an * (asterisk) mark to denote their other potential meanings (e.g. as well as, doing well).

-

3.

Excluding words that were part of the online newspaper’s sub-headings and tag lines (e.g. Trending News).

References

Ädel, A. (2010). How to use corpus linguistics in the study of political discourse. In A. O’Keeffe & M. McCarthy (Eds.), The routledge handbook of corpus linguistics (pp. 591–604). Routledge.

Amadeo, K. (2020, 31 July). Budget deficits and how to reduce them: Causes and effects. The Balance. https://www.thebalance.com/budget-deficit-definition-and-how-it-affects-the-economy-3305820

Anand, R. (2020, 15 December). Malaysia Parliament passes RM322.5 billion budget, proving majority support for PM Muhyiddin. The strait times. https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/se-asia/malaysias-parliament-ratifies-2021-budget-by-111-to-108-votes

Archer, D., Wilson, A., & Rayson, P. (2002). Introduction to the USAS category system—Benedict project report. www.comp.lancs.ac.uk/~paul/publications/usas%20guide.pdf

Baker, P., Gabrielatos, C., KhosraviNik, M., Krzyzanowski, M., McEnery, T., Wodak, R. (2008). A useful methodological synergy? Combining critical discourse analysis and corpus linguistics to examine discourses of refugees and asylum seekers in the UK press. Discourse & Society, 19(3), pp. 273–306.

Baker, P. (2004). Querying keywords: Questions of difference, frequency, and sense in keywords analysis. Journal of English Linguistics, 32(4), 346–359.

Baker, P., Gabrielatos, C., & McEnery, T. (2013). Discourse analysis and media attitudes: The representation of Islam in the British press. Cambridge University Press.

Bernama. (2020, December 15). Bursa Malaysia ends higher on Budget 2021 passing. Bernama. https://www.malaymail.com/news/money/2020/12/15/bursa-malaysia-ends-higher-on-budget-2021-passing/1932170

Binns, A. (2012). DON’T FEED THE TROLLS! Managing troublemakers in magazines’ online communities. Journalism Practice, 6(4), 547–562.

Bruns, A. (2008). Blogs, wikipedia, second life, and beyond: From production to produsage (Vol. 45). Peter Lang.

Chambers, S., & Gastil, J. (2020). Deliberation, democracy, and the digital landscape. Political Studies, 69(1), 3–6.

Chen, G. M., & Lu, S. (2017). Online political discourse: Exploring differences in effects of civil and uncivil disagreement in news website comments. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 61(1), 108–125.

Cindy Yeap. (2020, November 16). The State of the Nation/Economic Report: Expansionary Budget 2021 may still see add-ons. The Edge Markets. https://www.theedgemarkets.com/article/state-nationeconomic-report-expansionary-budget-2021-may-still-see-addons

Collins, L., & Nerlich, B. (2015). Examining user comments for deliberative democracy: A corpus-driven analysis of the climate change debate online. Environmental Communication, 9(2), 189–207.

Cull, B. W. (2011). Reading revolutions: Online digital text and implications for reading in academe. First Monday, 16(6).

Dahlgren, P., & Sparks, C. (2005). Communication and citizenship: Journalism and the public sphere. Routledge.

Flowerdew, L. (2004). The argument for using English specialized corpora to understand academic and professional language. In U. Connor & T. Upton (Eds.), Discourse in the professions: Perspectives from corpus linguistics (pp. 11–33). John Benjamins.

Habermas, J. (1989). On society and politics: A reader. Beacon Press.

Hartley, J. (2008). Problems of expertise and scalability in self-made media. In K. Lundby (Ed.), Digital storytelling, mediatized stories: Self-representations in new media (pp. 197–211). Peter Lang Publishing.

Hodges, A. (2015). Intertextuality in discourse. In D. Tannen, H. E. Hamilton, & D. Schiffrin (Eds.). The handbook of discourse analysis (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Jaworska, S. (2016). Using a corpusassisted discourse studies (CADS) approach to investigate constructions of identities in media reporting surrounding mega sport events: the case of the London Olympics 2012. In: I. R., Lamond, & L. Platt (Eds.), Critical Events Studies: Approaches to Research (pp. 149–174), Palgrave Macmillan.

Jenkins, H. (2006). Fans, bloggers, and gamers: Exploring participatory culture. NYU Press.

Kilgarriff, A., Baisa, V., Bušta, J., Jakubíček, M., Kovář, V., Michelfeit, J., Rychlý, P., & Suchomel, V. (2014). The sketch engine: Ten years on. Lexicography, 1(1), 7–36.

Lee, D. Y. W. (2008). Corpora and discourse analysis: new ways of doing old things. In V. K. Bhatia, J. Flowerdew & R. Jones (Eds.), Advances in Discourse Studies (pp. 86–99). Routledge.

Lee Heng Guie (2020, 13 October). Insight—Economy needs strong booster dose from budget. The star online. https://www.thestar.com.my/business/business-news/2020/10/13/insight---economy-needs-strong-booster-dose-from-budget

Lee, E., & Goh, J. (2020, 10 December) What’s next for Budget 2021 after being passed at the policy stage? The Edge. https://www.theedgemarkets.com/article/cover-story-whats-next-budget-2021-after-being-passed-policy-stage

Lew, R. (2009). The web as corpus versus traditional corpora: Their relative utility for linguists and language learners. In P. Baker (Ed.), Contemporary corpus linguistics (pp. 289–300). Continuum.

Light, R. (2014). From words to networks and back: Digital text, computational social science, and the case of presidential inaugural addresses. Social Currents, 1(2), 111–129.

Manosevitch, E., & Walker, D. M. (2009, April). Reader comments to online opinion journalism: A space of public deliberation. Paper presented to the 10th International Symposium on Online Journalism, Austin, TX.

Mautner, G. (2019). A research note on corpora and discourse: Points to ponder in research design. Journal of Corpora and Discourse Studies, 2, 2–13.

McNair, B. (2006). Cultural Chaos: Journalism and power in a globalised world. Routledge.

Ministry of Finance. (n.d.). Budget 2021 Official Website. Retrieved from http://www1.treasury.gov.my/index.php/en/

Moore, A., Fredheim, R., Wyss, D., & Beste, S. (2020). Deliberation and identity rules: The effect of anonymity, pseudonyms and real-name requirements on the cognitive complexity of online news comments. Political Studies, 69(1), 45–65.

Murugiah, S. (2020, November 26). KLCI retreats on regional pause, Budget 2021 concerns. The Edge Markets. https://www.theedgemarkets.com/article/klci-retreats-regional-pause-budget-2021-concerns

Ng, N. (2020, November 10). 4 weird things we found about Malaysia’s new budget 2021. CILISOS. https://cilisos.my/4-weird-things-we-found-about-malaysias-new-budget-2021/

Nordquist, R. (2020, January 30). Definition and examples of discourse: Glossary of grammatical and rhetorical terms. Thoughtco. https://www.thoughtco.com/discourse-language-term-1690464

Palanasamy, Y. (2020, 10 December). Putrajaya cuts RM45m from Budget 2021 allocations for controversial Jasa unit. Malay Mail. https://www.malaymail.com/news/malaysia/2020/12/10/putrajaya-cuts-rm45m-from-budget-2021-allocations-for-controversial-jasa-un/1930708

Papacharissi, Z. (2008). The virtual sphere 2.0: The Internet, the public sphere, and beyond. In Routledge handbook of Internet politics (pp. 246–261). Routledge.

Parker, I. & Burman, E. (1993). Against discursive imperialism, empiricism and constructionism: thirty two problems with discourse analysis. In E. Burman & I. Parker (Eds.), Discourse Analytical Research (pp. 155-172). Routledge.

Partington, A. (2010). Modern diachronic corpus-assisted discourse studies (MD-CADS) on UK newspapers: An overview of the project. Corpora, 5(2), 83–108.

Partington, A. (2018). Welcome to the first issue of the journal of corpora and discourse studies. Journal of Corpora and Discourse Studies, 1(1), 1–7.

Partington, A., Duguid, A., & Taylor, C. (2013). Patterns and meanings in discourse: Theory and practice in corpus-assisted discourse studies (CADS). John Benjamins.

Rayson, P. (2002). Matrix: A statistical method and software tool for linguistic analysis through corpus comparison. [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Lancaster University.

Roeder, S., Poppenborg, A., Michaelis, S., Märker, O., & Salz, S. R. (2005, March). “Public budget dialogue”–an innovative approach to e-participation. In International Conference on e-Government (pp. 48–56). Springer.

Rowe, I. (2015). Deliberation 2.0: Comparing the deliberative quality of online news user comments across platforms. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 59(4), 539–555.

Shank, G. (2002). Abductive multiloguing: The semiotic dynamics of navigating the net. The Arachnet Electronic Journal on Virtual Culture, 1(1), 1–13.

Shukry, A. (2020, 9 November). Malaysia’s opposition says budget may not pass if demands unmet. Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-11-09/malaysia-s-opposition-says-2021-budget-may-not-get-support

Sunstein, C. R. (2009). Going to extremes: How like minds unite and divide. Oxford University Press.

Tan, V. (2020a, 26 November). Malaysia’s parliament passes 2021 budget. Channel News Asia. https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/asia/malaysia-budget-2021-parliament-vote-confidence-test-muhyiddin-13637024

Tan, V. (2020b, 15 December). Malaysia’s 2021 budget passed at third reading in parliament. Channel News Asia. https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/asia/malaysia-2021-budget-parliament-third-reading-passed-muhyiddin--13775518

Tan, V. & Yusof, A. (2020, 6 November). Malaysia’s budget for 2021 is its biggest ever. Will it cushion the impact of COVID-19? Channel News Asia. https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/asia/malaysia-budget-2021-analysis-covid-19-bipartisan-13479452

Taylor, C. (2014). Investigating the representation of migrants in the UK and Italian press: A cross-linguistic corpus-assisted discourse analysis. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics, 19(3), 368–400

Terry, F. (2009). Democracy, participation and convergent media: Case studies in contemporary online news journalism in Australia. Communication, Politics and Culture, 42(2), 87–115.

The Edge Malaysia (2020, 28 November). Budget 2021: What’s next after the first hurdle? The Edge. https://www.theedgemarkets.com/article/budget-2021-whats-next-after-first-hurdle

The Star Online (2020a, 27 October). It’s back to the drawing board. The Star Online. https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2020a/10/27/its-back-to-the-drawing-board

The Star Online (2020b, 29 October). Let’s talk before tabling Budget 2021, Pakatan urges Muhyiddin. The Star Online. https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2020b/10/29/let039s-talk-before-tabling-budget-2021-pakatan-urges-muhyiddin

Tranchese, A. (2019). Using corpora to investigate the representation of poverty in the 2015 UK general election campaign. Journal of Corpora and Discourse Studies, 2, 65–93.

Watson, B. R., Peng, Z., & Lewis, S. C. (2019). Who will intervene to save news comments? Deviance and social control in communities of news commenters. New Media & Society, 21(8), 1840–1858.

Weeks, E. C. (2000). The practice of deliberative democracy: Results from four large scale trials. Public Administration Review, 60(4), 360–372.

Yusof, A. (2020, 27 November). Malaysia budget 2021: Five ‘refinements’ from the initial proposal and possible implications. Channel News Asia. https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/asia/malaysia-budget-2021-muhyiddin-tengku-zafrul-refinements-13649916

Zamith, R., & Lewis, S. C. (2014). From public spaces to public sphere: Rethinking systems for reader comments on online news sites. Digital Journalism, 2(4), 558–574.

Zhou, Y., & Moy, P. (2007). Parsing framing processes: The interplay between online public opinion and media coverage. Journal of Communication, 57(1), 79–98.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Joharry, S.A., Kasmani, M.F. (2023). Exploring Malaysia’s 2021 Budget through Corpus-Assisted Discourse Studies: (De)legitimation in Online News. In: Rajandran, K., Lee, C. (eds) Discursive Approaches to Politics in Malaysia. Asia in Transition, vol 18. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-5334-7_11

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-5334-7_11

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-19-5333-0

Online ISBN: 978-981-19-5334-7

eBook Packages: Literature, Cultural and Media StudiesLiterature, Cultural and Media Studies (R0)