Abstract

This first section shows that the concept of the interdependency of life domains is of utmost importance. Typically, such interdependency is detected when decisions, events and transitions in one life domain influence those in another, producing spillover effects. Spillovers across life domains take the form of resources generated or drained by one life domain that facilitate or hinder actions and well-being in another life domain. In this synthesis, we discuss how positive and negative spillovers across life domains can lead to a better understanding of life course vulnerability. We also relate the spillovers across life domains of related individuals and the way in which spillovers are regulated by the structural embeddedness into specific contexts. We illustrate our purpose through examples taken from research carried out by LIVES research program. We conclude by arguing that life domains interdependencies call for life course policies that explicitly consider spillover effects. Current policies addressing a specific life domain at the time have often unintended consequences that shall not be neglected. For instance, policies increasing pension age, do not only shape the employment trajectories, but have also have consequences on time available for leisure and care as well as on opportunities to relocate after retirement.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

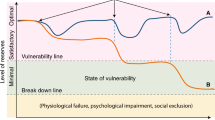

The life course approach to vulnerability (Spini et al., 2017; Spini & Widmer, (introduction chapter) posits that vulnerability is a dynamic process of accumulation/loss of reserves and resources over the life course while facing life stressors (critical life events, transitions, etc.). Individuals have resources (e.g., time, money, relations, human capital) of different natures and in different amounts and use them to engage in activities belonging to various life domains to achieve different goals. Such resources are often limited, and if drained by one life domain, they may hinder activities and well-being in another life domain. Time is a typical example: Increasing the time spent on work-related activities often means reducing the time available for leisure and family life, with potential negative effects on life satisfaction and relationship quality. However, resources may also be generated within one life domain and, as a side effect, facilitate activities in other domains. For instance, if we take time as a resource, in the classic and highly debated household specialisation theory of Becker (1965, 1991), marriage may bring about a specialisation and division of roles that, in turn, may represent a resource gain since at least one of the partners can free up resources, including time, from family life and invest them in labour market activities.

Resources cannot always be allocated as desired to reach multiple and potential conflicting life goals. Activities pertaining to different domains may then compete for such resources, thereby necessitating trade-offs (time for family or work or leisure, money for health or leisure). Such a process potentially gives rise to different investment strategies in resource distribution across life domains and over time. In contrast, other types of resources, such as personality traits, are by definition not finite and may be used to sustain different activities across domains without producing trade-offs but, rather, by being subsidiary to other resources.

This situation raises an important point of the life course paradigm (Giele & Elder, 1998): the multidimensionality of the life course. Life domains are strictly interconnected: Decisions and events occurring in one domain may exert a strong influence on another life domain, either in the short or long term, thereby creating spillover effects (Bernardi et al., 2019). The intertwining of family and working life is a classic example: There is consistent evidence of the differentiated impacts of women’s employment on fertility (e.g., Matysiak & Vignoli, 2008) or the labour market disadvantages faced by mothers—the so-called ‘motherhood penalty’ (e.g., Budig & England, 2001). In terms of resources and reserves, as mentioned above, when life domains compete for resources, such competition may lead to negative spillovers across life domains; in contrast, when resources are transferred across domains, they may create positive spillover effects (Bernardi et al., 2017; Freund et al., 2014; Hanappi et al., 2017; Roeters et al., 2016).

In this vein, vulnerability can be viewed in terms of how and to what extent individuals are able to mobilise their reserves to cope with (life) stressors in one or multiple linked life spheres. Life stressors, such as life hazards, events and transitions, may increase or reduce available resources in related domains. For instance, changing jobs might increase the amount of economic resources available but simultaneously reduce the time for leisure and family life activities. The literature has also noted great heterogeneity in the observed effects. Individuals respond differently while facing similar stressors, according to the reserves available and their ability to mobilise them. For example, Struffolino et al. (2016) showed that among lone mothers, the resources available in terms of employment stability and educational level mediated the negative effect of becoming a lone mother on mental health.

The interconnection among life domains, despite being a pivotal aspect of the study of vulnerability over the life course, cannot be investigated in isolation from two other key points that have already emerged in the introduction (Spini & Widmer, introduction chapter): the role of time and the interconnection among related individuals. In the conceptualisation of the life course as a series of relationships proposed by Bernardi et al. (2019)—the so-called life course cube—the dimensions of time, domains, and levels (including the micro/meso/macro levels) represent the three main axes of the cube at which developmental, behavioural, and societal processes occur.

The Role of Time

Time emerges as a key aspect in the analysis of vulnerability over the life course and the interconnections across life domains. Time is one of the three dimensions of the life course cube (Bernardi et al., 2019) and is embedded in the definition of vulnerability as a dynamic process (Spini et al., 2017, see also Spini & Widmer, this book/this volume).

Within the life course framework, time is a multifaceted concept. It can be viewed simply as a measure to study the evolution over time of a certain characteristic of interest, such as health, employment status, living arrangement, to trace the so-called life trajectories. It can also be viewed as an indicator of when an individual experienced a given event and transition in the study of, for instance, the time to an event (e.g., timing of divorce, age at leaving home). When interpreting vulnerability as individuals’ (in)ability to accumulate and mobilise resources in response to critical life events, the timing of the events becomes crucial: The moment in life at which the stressor occurs matters. Losing a job at the beginning of one’s career or at age 50 does not have the same effect on future employment perspectives, for example. Moreover, not only the timing but also the spacing between events matters. The combination of timing and spacing defines the distribution of events across the life course. Such distribution matters for crucial life course outcomes such as levels of well-being. The study by Comolli et al. (2021) advanced this line of research by proposing an innovative indicator of life event concentration that measures its effect on well-being later in life across different life stages.

Time can also be viewed in terms of the time schedule, i.e., the time clocks that prescribe individual goals and decisions. The time schedule can refer either to a single life domain or to multiple domains (e.g., becoming a parent and having a stable job by age 30) and may involve different levels. We can think of an individual time clock and the societal time clock (Neugarten & Lowe, 1965; Sanchez Mira & Bernardi, 2021; Settersten & Hagestad, 1996a; 1996b). Individuals have internal motivations and plans to reach certain goals in life and might set—consciously or unconsciously—individual time clock(s). Furthermore, time clocks are also set at the macro (policy makers) and meso levels (society, social network), thereby creating societal time schedule(s). Norms, both legal and social, might define the age and timing of events. At the meso level, for instance, social norms are a set of regulatory tools that establish a predictable order or timetable of events (Billari & Liefbroer, 2007). Age norms, for instance, set a sort of ‘age limit’ or ‘appropriate timing’ for certain transitions, such as leaving home, getting married, and having a child (e.g., Aassve et al., 2012). At the macro level, norms (social policies) play a crucial role and set some age ‘restrictions’. Retirement, marriage, sexual intercourse, and schooling are domains that, in many contexts, are highly normatively regulated with respect to age. All these different clocks may tick at the same time and may not always proceed in the same direction in their influence on individual behaviours across the life course.

The Interdependence of Related Individuals

The third aspect that might play a role in shaping the ability to access and mobilise reserves when needed is the interdependence among individuals. Changes in one person’s life patterns may lead to changes in other people’s lives and to a dependence on the attitudes and behaviours of members of the same group or network (household, working place). These are so-called crossover effects (Bernardi et al., 2019). Similarly, the accumulation or loss of resources might be due to the relationship across individuals: Social capital is a prototypical example of this process.

Empirical research on Elder’s concept of linked lives (Elder, 1994) has traditionally focused on interdependences across siblings or partners and has shown, for instance, similarities in preferences and outcomes among them. Examples include studies on the effect of parental characteristics and events (joblessness, teenage pregnancy, health status, level of education) on children’s development and outcomes (education, earnings, health, lifestyle). Studies on intergenerational links (usually across two generations: parents and kinship) have pointed out several forms of material and immaterial transfers of resources across generations, including grandparental care for grandchildren (Aassve, Meroni, & Pronzato, 2012; Albertini et al., 2007). Other studies have examined crossover effects across friends, schoolmates, neighbours and coworkers (e.g., Balbo & Barban, 2014; Bernardi, 2003; Pink et al., 2014).

The Multidimensional Perspective of Vulnerability Discussed in This Section

The five chapters included in this first section (Spini & Widmer, this book/this volume) offered compelling examples of the multidimensionality of the life course and discuss the intertwinement of life domains and the presence of spillover effects from different disciplinary perspectives.

LeGoff, Ryser and Bernardi, as well as Jopp and colleagues (Chap. 2 and Chap. 6), discussed some of the work conducted by LIVES on the links among life stressors in multiple life domains and wellbeing. Specifically, Le Goff and colleagues examined different dimensions of well-being from a sociodemographic perspective, while Jopp et al. used a psychological lens to discuss the effect of union dissolution, both divorce and widowhood, on well-being among older adults in Switzerland. Both chapters stressed the roles of individual characteristics (e.g., gender, family configuration) and intrapersonal resources available (i.e., psychological resilience, personality traits) in explaining the different ways individuals cope with critical events. Broadly speaking, life stressors in several different life domains have effects not only on physical and mental health but also on changes in behaviour and life conditions. Studies have shown an increasing risk of union dissolution after job loss (e.g., Charles & Stephens Jr, 2004; Di Nallo et al., 2020), change in social participation after becoming a widow(er) (Bolano & Arpino, 2020), or loss of wages and economic opportunities among new mothers (Oesch et al., 2017).

Considering individuals’ psychological and behavioural involvement, Schüttengruber, Krings and Freund (Chap. 3) underlined the role of conflict and facilitation within and among life domains in the pursuit of multiple life goals. An interesting perspective on spillover effects addressed in this chapter is the role of boundaries between domains. Domain boundaries influence the way in which people manage their activities in different life domains. However, the theoretical debate and the empirical evidence on whether it is more beneficial for decision making and life goal achievement to have strict or blurred boundaries across domains (physical, temporal, emotional, cognitive, and relational) is still open. This kind of research may certainly enrich the study of vulnerability over the life course related to spillovers across life domains.

Using a (socio)economic lens, Lalive, Oesch and Pellizzari (Chap. 4) discussed the link between personal relationships and employment outcomes. As argued by the authors, there are positive and negative spillover effects. Developing personal contacts and social connections might, on the one hand, result in an improvement of the labour market position—for instance, enabling access to a larger set of information—but, on the other hand, personal contacts, or more broadly workers’ family status, can also hamper employment prospects. The motherhood wage penalty is a typical example: Women with children might be perceived by the prospective employer as less dedicated to the job and hence less productive than a childless counterpart receiving a lower wage (e.g., Budig & England, 2001).

Cangià, Davoine and Le Feuvre (Chap. 5) used a gender perspective to discuss the intertwinement between transnational mobility and family- and work-related decisions. They explored a large variety of mobile people: those who moved alone or already in a couple, from less-qualified workers to highly skilled migrants, as well as those who moved ‘voluntarily’ to those who were ‘forced’ to move. The different sets of resources and reserves available exerted differentiated impacts on family and work trajectories. The authors stressed the crucial role of gender regimes and how international migration can be a potential source of vulnerability even for a group of individuals, such as highly skilled workers (e.g., university researchers, managers), who are conventionally not considered a vulnerable population. A residential move to another country is already associated with hardship during the integration process at arrival (‘new place’) when it is an individual who moves. When a couple undertakes such a move, transnational mobility might additionally require reconfiguration of the gendered division of roles and priorities within the couple, with potentially negative effects on relationship quality and overall wellbeing. The strategies for facing other life events that might happen subsequently to the move can also be challenging in a new environment. The authors, using Switzerland as a case study, reported several examples of difficulties faced by mobile couples—even those highly skilled and, thus, potentially with higher economic resources—in, for instance, dealing with the birth of a child in a foreign country. The result, in some cases, is the decision of one parent to abandon their preferred career to care for the newborn.

While the chapters included in this section focused their attention on spillover effects, i.e., the strict interconnection of the allocation of reserves across life domains, in all the works discussed here, we can clearly identify the role of time and the interdependence across individuals—crossover effects—as key components in the study of life course vulnerability.

The contribution by Lalive and colleagues (Chap. 4) addressed crossovers by focusing on sociability—the development of a social network as the result of the interdependence and interaction among individuals—and its effect on a given outcome (employability). Similarly, Cangià and colleagues (Chap. 5) discussed couple-level trajectories of transnational mobility and rearrangement that occurred within the couple in the organisation of gendered roles, offering another classical example of ‘linked lives’. The time dimension emerged clearly in all chapters. Starting from the stress proliferation theory (Pearlin, 2010) and building upon the definition of life course vulnerability by Spini et al. (2017), LeGoff and colleagues (Chap. 2) argued for the relevance of taking a dynamic (longitudinal) perspective in the study of variations in well-being in response to life stressors. This approach was also used and discussed in Jopp et al.’s study on the effect of bereavement among older adults in Switzerland. In one study (Spahni, Morselli, Perrig-Chiello, & Bennett, 2015), three post-bereavement trajectories were identified: Two groups, the Resilients and Copers, showed a stable level of distress, whereas a third group, the Vulnerables, showed increasing levels of depressive symptoms. According to the results of this study, interpersonal resources played an important role in predicting the potential post-bereavement trajectory.

Chapter 5 by Cangià et al. centred on the notion of mobility and change over time of gender roles and career paths of highly qualified workers. Similarly, the chapter by Lalive and colleagues showed how building social connections or given life events (e.g., getting married, having a child) can influence future employment prospects. Time in terms of the moment in life at which an event happens was explicitly discussed in Chap. 3 by Schüttengruber and colleagues, who focused specifically on boundary management and attempts to reach multiple life goals in middle adulthood, a moment of life defined by the authors as the ‘rush hour of life’. Middle adulthood is indeed a life stage during which individuals have to play multiple roles at the same time (worker, parent, partner, caregiver for their own children and for an older parent) and is potentially full of events (e.g., death of parents, transition to grandparenthood).

The Multidimensionality of the Life Course: The Need for Life Course Policies and Implications for Future Life Course Studies

Studies on life course vulnerability should simultaneously consider and discuss all three aspects: interconnection among individuals, intertwined life domains and the role of time. However, in practice, the majority of studies conducted thus far have focused on only one aspect at a time, or two at best. Research integrating spillover and crossover effects from a longitudinal perspective is still needed (Bolano & Bernardi, 2021).

Recently, several studies using dyadic data from large social surveys have examined the effect of the diffusion of resources and stress across life domains of people who are strictly interconnected (often partners, for example, as discussed in Cangià and colleagues’ contribution to this volume). However, these studies have focused on outcomes that are couple level by definition, such as having a child and moving to a new place (e.g., Hanappi et al., 2017; Testa & Bolano, 2021). It is thus to be expected that both partners’ trajectories would influence couple-level outcomes. More interesting is to analyse to what extent decisions made by an individual in a certain life domain exert an impact on a related individual in other life domains. Lam and Bolano (2019) examined the spillover effect on the physical and mental health of social participation across couple members. They found that not only is being socially engaged associated with a better level of health but also that the active spouse’s engagement influences the level of health of his or her partner. Bolano and Bernardi (2021) took an integrative perspective to examine spillover and crossover effects simultaneously by analysing the interdependence between the choice of early retirement among middle-aged workers in Europe and the transition to grandparenting the first child of their adult children.

The increasing availability of linkable register and survey data that can enable a comprehensive analysis of the interdependencies among the three dimensions of the life course offers several opportunities for vulnerability research in the near future. Thanks to the widespread diffusion of social surveys covering multiple life domains and multiple linked individuals as well as the availability of administrative record linkages in many countries, researchers have potential access to a large set of detailed information to investigate interactions as well as the role of time across levels and across domains. In addition to extending the knowledge on vulnerable trajectories, such research will also contribute to promoting the need for life course policies within political agendas.

When setting social policies, policy makers should give due consideration to the entirety of the life course of the individual and the implications of the policy in other life domains with respect to other individuals and over time. A holistic view of life is needed in legislation. For instance, with the increase in life expectancy, many countries are raising the retirement age for both men and women. This kind of policy, although necessary to keep the balance between retired individuals and the active population, should not be put in place without considering spillover and crossover effects that such an increase in retirement age might have. The link between retirement and becoming a grandparent can be formalised as a form of spillover (work-related decisions and family domain) and crossover (vertical ties across generations) effects over time (Bolano & Bernardi 2021). Alternatively, we can examine such effects in terms of the link between the institutional retirement ‘clock’ of older adults and the (societal and individual) fertility ‘clock’ of their adult children. In many countries with relatively few childcare facilities available, grandparents are crucial care providers for their grandchildren. Keeping individuals active in the labour market might, therefore, reduce the time available for grandparent care for grandchildren, with possible effects on the children of the workers concerned in the new law in terms of fertility decisions, family-work life balance, decisions on labour markets, and so on. Under this perspective, an increase in retirement age should be combined with compensatory policies to assist families’ childcare needs, for instance by increasing the offer of affordable and high-quality childcare facilities. Life course studies of this kind, directly addressing the presence of multiple clocks and multiple interdependencies across linked individuals as well as their combined effects, suggest the importance of adopting a holistic approach in designing social policies.

References

Aassve, A., Meroni, E., & Pronzato, C. (2012). Grandparenting and childbearing in the extended family. European Journal of Population, Springer; European Association for Population Studies, 28(4), 499–518. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-012-9273-2

Albertini, M., Kohli, M., & Vogel, C. (2007). Intergenerational transfers of time and money in European families: Common patterns – different regimes? Journal of European Social Policy, 17(4), 319–334.

Balbo, N., & Barban, N. (2014). Does fertility behavior spread among friends? American Sociological Review, 79(3), 412–431.

Becker, G. S. (1965). A theory of the allocation of time. The Economic Journal, 75(299), 493–517.

Becker, G. S. (1991). A treatise on the family (Enlarged ed.). Harvard University Press.

Bernardi, L. (2003). Channels of social influence on reproduction. Population Research and Policy Review, 22(5), 427–555.

Bernardi, L., Bollmann, G., Potarca, G., & Rossier, J. (2017). Multidimensionality of well-being and spillover effects across life domains: How do parenthood and personality affect changes in domain-specific satisfaction? Research in Human Development, 14(1), 26–51.

Bernardi, L., Huinink, J., & Settersten, R. A., Jr. (2019). The life course cube: A toll for studying lives. Advances in Life Course Research, 41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcr.2018.11.004

Billari, F. C., & Liefbroer, A. C. (2007). Should i stay or should i go? The impact of age norms on leaving home. Demography, 44, 181–198. https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.2007.0000

Bolano, D., & Arpino, B. (2020). Life after death. Widowhood and volunteering gendered pathways among older adults. Demographic Research. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2020.43.21

Bolano, D., & Bernardi, L. (2021). Transition to grandparenthood and early retirement: Interdependencies of life domains across generations, presented at the Annual conference of the Population Association of America 2021.

Budig, M. J., & England, P. (2001). The wage penalty for motherhood. American Sociological Review, 66, 204–225.

Charles, K. K., & Stephens, M., Jr. (2004). Job displacement, disability, and divorce. Journal of Labor Economics, 22(2), 489–522.

Comolli, C. L., Bolano, D., Bernardi, L., & Voorpostel, M. (2021). Concentration of critical events over the life course and life satisfaction later in life. PAA Annual Meeting.

Di Nallo, A., Lipps, O., Oesch, D., & Voorpostel, M. (2020). The effect of unemployment on couples separating. Panel evidence for Germany, Switzerland and the United Kingdom. DIAL Working Paper Series 14/2020.

Elder, G. H. (1994). Time, human agency, and social change: Perspectives on the life course. Social Psychology Quarterly, 57(1), 4–15. https://doi.org/10.2307/2786971

Freund Alexandra, M., Knecht M., & Wiese Bettina, S. (2014). Multidomain engagement and self-reported psychosomatic symptoms in middle-aged women and men. Gerontology, 60(3), 255–262. https://doi.org/10.1159/000358756

Giele, J. Z., & Elder, G. H., Jr. (Eds.). (1998). Methods of life course research: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. Sage Publications, Inc.

Hanappi, D., Ryser, V. A., Bernardi, L., & Le Goff, J. M. (2017). Changes in employment uncertainty and the fertility intention–realization link: An analysis based on the Swiss household panel. European Journal of Population, 33(3), 381–407. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-016-9408-y

Lam, J., & Bolano, D. (2019). Social and productive activities and health among partnered older adults: A couple-level analysis. Social Science & Medicine, 229, 126–133.

Matysiak, A., & Vignoli, D. (2008). Fertility and women’s employment: A meta-analysis. European Journal of Population/Revue européenne de Démographie, 24(4), 363–384.

Neugarten, B. L., Moore, J. W., & Lowe, J. C. (1965). Age norms, age constraints, and adult socialization. The American Journal of Sociology, 70(6), 710–717.

Oesch, D., McDonald, P., & Lipps, O. (2017). The wage penalty for motherhood: Evidence on discrimination from panel data and a survey experiment for Switzerland. Demographic Research, 37, 1793–1824.

Pearlin, L. I. (2010). The life course and the stress process: Some conceptual comparisons. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 65(2), 207–215.

Pink, S., Leopold, T., & Engelhardt, H. (2014). Fertility and social interaction at the workplace: Does childbearing spread among colleagues? Advances in Life Course Research, 21, 113–122.

Roeters, A., Mandemakers, J. J., & Voorpostel, M. (2016). Parenthood and well-being: The moderating role of leisure and paid work. European Journal of Population, 32(3), 381–401. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-016-9391-3

Sanchez Mira, N., & Bernardi, L. (2021). Relative time in life course research. Longitudinal and Life Course Studies. https://doi.org/10.1332/175795920X15918713165305

Settersten, R. A., Jr., & Hagestad, G. O. (1996a). What’s the latest? Cultural age deadlines for family transitions. Gerontologist, 36, 178–188.

Settersten, R. A., Jr., & Hagestad, G. O. (1996b). What’s the latest? Cultural age deadlines for family transitions. Gerontologist, 36, 602–613.

Spahni, S., Morselli, D., Perrig-Chiello, P., & Bennett K. M. (2015). Patterns of Psychological Adaptation to Spousal Bereavement in Old Age. Gerontology, 61(5), 456–68. https://doi.org/10.1159/000371444. Epub 2015 Feb 21. PMID: 25720748.

Spini, D., Bernardi, L., & Oris, M. (2017). Toward a life course framework of vulnerability. Research in Human Development, 14(1), 5–25.

Struffolino, E., Bernardi, L., & Voorpostel, M. (2016). Self-reported health among lone mothers in Switzerland: Do employment and education matter? Population, 71(2), 187–213. https://doi.org/10.3917/pope.1602.0187

Testa, M. R., & Bolano, D. (2021). When partners’ disagreement prevents childbearing: A couple-level analysis in Australia. Demography Research, 44(33), 811–828. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2021.44.33

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Bernardi, L., Bolano, D. (2023). Synthesis: A Multidimensional Perspective on Vulnerability and the Life Course. In: Spini, D., Widmer, E. (eds) Withstanding Vulnerability throughout Adult Life. Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-4567-0_7

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-4567-0_7

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-19-4566-3

Online ISBN: 978-981-19-4567-0

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)