Abstract

This chapter reflects on the twelve-year Swiss research program, “Overcoming vulnerability: Life course perspectives” (LIVES). The authors are longstanding members of its scientific advisory committee. They highlight the program’s major accomplishments, identify key ingredients of the program’s success as well as some of its challenges, and raise promising avenues for future scholarship. Their insights will be of particular interest to those who wish to launch similar large-scale collaborative enterprises. LIVES has been a landmark project in advancing the conceptualization, measurement, and analysis of vulnerability over the life course. The foundation it has provided will direct the next era of scholarship toward even greater specificity: in understanding the conditions under which vulnerability matters, for whom, when, and how. In a process-oriented life-course perspective, vulnerability is not viewed as a persistent or permanent condition but rather as a dormant condition of the social actor, activated in particular situations and contexts.

The authors of this conclusion have served as core members of the scientific advisory committee to the Swiss National Center of Competence in Research (NCCR), “LIVES: Overcoming Vulnerability: Life Course Perspectives,” a partnership of the University of Geneva and University of Lausanne (Phase 1, 2010–2014; Phase 2, 2014–2018; Phase 3, 2019–2022) funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF). Julie McMullin (Western University, Canada) and the late Victor Marshall (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill) were also core contributing members of the advisory committee for the first two phases. The Appendix B charts the history of the LIVES program and names other important contributors to the program or the centers on which it was built.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

This book represents a synthesis of theories, concepts, and empirical illustrations of core scientific contributions of the LIVES research program as it has unfolded over the years. The first chapter introduced some of the program’s starting-point definitions of “vulnerability” and its significance within a life course framework. The remaining sections take up the cross-cutting aspects of vulnerability. First, they refer to vulnerability as a multidimensional process: Vulnerability spans and spills over to many life domains, such as family, work, and health. Secondly, they view vulnerability as a multilevel process: Vulnerability is anchored in phenomena that exist on and interact across micro, meso, and macro levels of analysis—from cognitive and personality characteristics of the individual to the social system. Third, they refer to vulnerability as a multidirectional process: In adding the dimension of time, multiple trajectories of experience and functioning yield unequal levels and types of vulnerability.

These features mean that vulnerability is inherently a transdisciplinary and life course matter. It is therefore important to not only understand the forms, sources, and consequences of vulnerability in distinct life phases, but also to understand how it unfolds over time—for example, how its dynamics slow, stop, or even reverse course. These characteristics, in turn, demand measures and methods that are sensitive enough to capture these processes for people of different ages, and to capture them longitudinally.

In having witnessed and shaped the evolution of this research program, our task here is fourfold: to reflect on some of its (1) major accomplishments, (2) ingredients of success, (3) barriers to success, and (4) directions going forward.

Major Accomplishments

LIVES was the first Swiss National Center for Competence in Research (NCCR) in the social sciences. This alone is an extraordinary accomplishment. Standard measures of success, such as publications in major journals and other scientific outlets, are important. To date, we count 909 journal articles, 293 book chapters, 88 books, and 1707 academic events. Beyond these quantitative criteria, we would like to briefly highlight four major accomplishments of the research program in advancing (1) the concept of vulnerability, (2) data, measures, and methods, (3) education and training, and (4) social relevance.

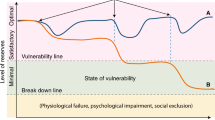

First, in terms of the basic concept, vulnerability was in the beginning of the program understood pragmatically. It was taken at face value, an umbrella term that could potentially capture many empirical phenomena of interest. Only later did it reveal itself to be more demanding in theoretical rigor and depth, with the leaders developing an integrative theoretical paper on vulnerability to both organize the program and stimulate further research in the field, notably on notions of latent/manifest vulnerability and the role of norms and institutions in this regard (Spini et al., 2017); a sequential view of vulnerability in three steps of being at risk for it, of having difficulty in adapting to stressors, and of having difficulty recovering or profiting from opportunities in a specific time frame; and finally, the need to consider resources and reserves, as well as processes of growth, robustness, and resilience, as intrinsic processes of vulnerability in a life course framework (Spini & Widmer, this volume).

Second, from the vantage point of data, measures, and methods, there are a few particularly important achievements. LIVES has shined a light on issues related to vulnerability in Switzerland as a case study. Switzerland has not been included in some major international data collection efforts (e.g., the Generations and Gender Programme). The in-depth attention to Switzerland in LIVES, especially through modules associated with the Swiss Household Panel, has been instrumental in bringing Switzerland to the forefront of international discussions. As a corollary, Switzerland, because of LIVES, developed a much wider international presence in the social and behavioral sciences and brought attention to Swiss researchers.

The case of Switzerland demanded greater justification and explanation of context. It posed special challenges because, while small, it is highly differentiated linguistically, culturally, and politically, as reflected in the history and political autonomy of the present-day 26 cantons. On the one hand, this diversity makes Switzerland a unique social laboratory: it has the potential to generate and test theories and hypotheses that are not relevant or cannot be tested in other contexts. On the other hand, this explains why a program such as LIVES encountered challenges establishing a research and doctoral program at the Swiss federal level. The 10 universities are run at the cantonal level, and all have slightly or even widely different study regulations.

Through LIVES, the use of the Swiss Household Panel has greatly increased because of both the productivity of LIVES researchers and the financial investments of the program in panel data collection. The program has also been instrumental in fostering research methods to analyze longitudinal data. The Institute for the Study of Biographical Trajectories (ITB) at the University of Lausanne (2001–2009) and the creation of the Swiss Center for Expertise in the Social Sciences (FORS) in 2008, with its location in Lausanne and its Swiss Research Infrastructure Roadmap, have been important in launching LIVES, especially in building modules and collecting specialized data to examine connections between vulnerability and the life course. For example, ITB was instrumental in adding more life course content to the Swiss Household Panel, including a retrospective module in one of the early waves to give greater attention to the past lives of respondents. These collaborations increased the scientific value of the project. Of course, LIVES also had other data collection and analysis efforts across the many projects associated with it.

Third, education and training, along with emphasis on equal opportunities, have offered another major dimension for advancing the treatment of vulnerability in a life course perspective. The introduction of NCCRs in the late 1990s by the federal government and the Swiss National Science Foundation was a decisive step for more harmonized doctoral training and for getting researchers from various universities to work together.

Since the beginning of LIVES at least 72 doctoral students have completed their PhDs. About half of the doctoral students have been international students. LIVES does not itself deliver a full-fledged doctoral program; rather, it provides a common core of seminars and experiences that complement the training that students receive in their own university. In addition to the doctoral students, the program has also funded postdocs who have been placed in specific research projects and trained in the context of the larger program. LIVES has also hosted or been involved in co-organizing a handful of “winter schools” in partnership with other universities to provide doctoral students from other countries training in vulnerability and/or life course studies.

LIVES has therefore been an advantage to doctoral programs in Lausanne and Geneva for recruiting excellent doctoral students and postdoctoral fellows in the social sciences, and it has offered a sizable and unusual source of funding for students. Through these educational and training efforts, the program has produced a strong professional network for doctoral and postdoctoral students that would not otherwise have been possible and will continue to impact their international careers and science itself.

Fourth, the program has drawn attention to the social relevance of vulnerability through its knowledge transfer and social policy efforts. These include, for instance, the periodic “LIVES Impact” policy briefs, which are sent to targeted people and institutions in communities and cantons and across Switzerland; many of them have received significant attention via downloads and public discussion (e.g., a special issue on how to address public confidence during the COVID-19 pandemic). The Dictionary of Swiss Social Policy, now in its second edition, is another good example. So, too, is the projected creation of a subunit within the future LIVES Center called LIVES Social Innovation, in collaboration with the regional University of Applied Sciences and Arts in Western Switzerland (HES-SO). This subunit will develop prototypes of social interventions in various problem fields. There have also been innovative activities to reach new audiences, such as a game developed for elementary school students to facilitate discussion about their aspirations and expectations for adulthood and a major collaborative gallery exhibit and art book of photographs depicting the expression of vulnerability in the life course.

Ingredients for Success

There are some key factors that contributed to the success of LIVES, which may be of interest to those who wish to launch similar large-scale collaborative enterprises. A central ingredient was a strong network of senior scientists. Another was its interdisciplinary orientation, grounded in a common concept and theoretical framework attractive and open enough to incorporate and join different perspectives. As already noted, it was reinforced by a doctoral program and the involvement of junior researchers, postdoctoral fellows, and doctoral students.

Another crucial element was an already-established intellectual tradition and organizational structure on which to build. LIVES had its origins in the objectives and partnerships in lifespan developmental psychology and gerontology that began between scholars in Geneva and Lausanne in the 1990s. The Center of Gerontology (CIG, now CIGEV) at the University of Geneva and the ITB at the University of Lausanne had created the group PAVIE (short for PArcours de VIE, or “life course”; see also Appendix B). Within the PAVIE center, a number of faculty had already been working on the concepts of “frailty” and “transition,” exploring similarities and differences between “lifespan” and “life course” perspectives, and finding common language to foster interdisciplinary exchanges. These cross-institutional and interdisciplinary teams made it possible to apply for the NCCR funds. There had also been two prior attempts to propose an NCCR by these groups, proposals that were rejected but had nonetheless brought attention to those involved and paved the way for LIVES.

The provision of significant financial resources through the NCCR made it possible to create a research and training enterprise that was much larger and crossed multiple institutions, with co-directors from both Geneva and Lausanne and an administrative infrastructure designed to integrate faculty and students at these and other institutions across Switzerland. LIVES has therefore established durable links across institutions and disciplines. When LIVES started, psychology (with the exception of social psychology) was not well represented in the construction of “social sciences.” LIVES incorporated psychology into its vision from the start. This interdisciplinarity was central to securing long-term funding.

Early on, after having toyed with concepts such as frailty and resilience, a choice was made to center the program around the core concept of vulnerability, which was relatively new to the social sciences at large. It brought an element of novelty and created conditions to advance interdisciplinary theories and research because it could be examined from multiple angles and stretched across disciplines and fields. The concept of vulnerability captured the imagination of the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF), but it also took a handful of years to develop a clearer concept and propositions to anchor the program. In the first phase, there was no shared definition or framework. It began to emerge during the second phase at the urging of the SNSF review panels and our advisory group and came to more complete fruition by the third phase. It takes time for a large interdisciplinary group to agree on shared concepts and perspectives and infuse them systematically to bring coherence and integrity to the whole. The core concept needed to be incorporated into the larger theoretical perspectives of the “life course” in sociology and the preferred label in psychology, “life span.” That is, it had to be extended to examine variability across age and its dynamics over time, across life domains, and at different levels of analysis, as noted earlier. Between the two labels, there was a large space of interdisciplinary complementarity on which LIVES could capitalize—especially in forcing the psychologists and sociologists to get out of their respective “black boxes” of agency and structure.

Success hinged on the active cooperation of multiple institutions. There were important strategic decisions to be negotiated in the choice of top-level leaders and the allocation of resources across the institutions. The SNSF required that the associated universities build capacity and commit resources to complement its investment, including hiring permanent faculty to ensure the representation of these substantive areas of concern in the long term. The NCCRs are meant to transform institutions in ways that are self-sustaining and durable once the SNSF funding ends.

There was a nimble structure of research projects (“IPs”) and project leadership over the three phases, some of which continued in new forms and others of which were funded for just one phase or later combined to optimize their work. During the second phase, LIVES introduced the four cross-cutting issues (“CCIs”) described earlier: vulnerability as multidimensional, multilevel, and multidirectional, and the study of vulnerability as requiring multiple methods. These explicitly organized the intellectual agenda of the third phase and played important roles in fostering the coherence of the program.

Just as there was top-level direction provided by the co-leaders from Lausanne and Geneva, there was also sensitivity in determining leadership and membership in research projects and cross-cutting cores to represent and reach across the two universities. The two universities are also relatively close in proximity, separated by about an hour by car or train, making it possible to attend meetings, events, and retreats in person. Because the two universities have traditionally been rivals, LIVES has been remarkable in creating a longstanding partnership and shared stakeholders in deep collaboration.

The presence of our independent interdisciplinary multinational advisory committee—one that was largely stable in its composition across the three phases—was also an element in the success of the program. We accumulated many years together as a group, agreeing to an open and transparent relationship with the program’s leadership and gaining important backstage knowledge of its administrative, financial, and personnel challenges. We also served in ways that go beyond most advisory panels, providing a firm hand in shaping research emphases and questions, reviewing project proposals and recommending funding priorities, serving as a sounding board for leaders, and helping to navigate organizational changes. We backed up the leaders when they needed to do hard things and forced difficult conversations.

Challenges to Success

A requirement of the NCCRs is that the funded institutions must make long-term commitments to a topic that is important enough to catalyze collaboration and gain recognition. The work must be ground-breaking and open new possibilities. Another highly relevant criterion is that the NCCR must generate “added value” in the cross-fertilization of disciplines and programs. That is, it should yield something different than the institutions would have been able to do on their own and something greater than the simple sum of its parts.

A major challenge has expectedly been found in integrating diverse participants—who often had no prior experience collaborating with each other, let alone crossing disciplinary frontiers—into a common enterprise. As noted earlier, the second phase brought a clearer conception of “vulnerability,” and the third phase brought an explicit focus on the “cross-cutting issues” of domains, levels, time, and research methods. To work in truly interdisciplinary ways takes a great deal of time and requires intentional cultivation. This applied to the LIVES scholars, most of whom had traditional disciplinary degrees and appointments in traditional disciplinary departments, especially psychology and sociology. The pairing of “life span” and “life course” approaches was also not easy, as there were different disciplinary preferences for collaboration, different vocabularies, and different incentives, worldviews, and values assigned to types of scholarly effort and products (e.g., books versus journal articles).

Throughout the program, there have been challenges in getting people aligned around and committed to the project. Some of this has been about personalities and competing reward structures and obligations. What would LIVES offer as an incentive for giving time, being involved, and taking responsibility? How would these efforts affect one’s evaluation and progress in other roles? One important incentive for joining LIVES and submitting to its expectations was the prospect of long-term research funding. A typical research project with the SNSF lasts a maximum of three years, recently changed to four years, renewable only in exceptional cases; in contrast, an NCCR might last up to 12 years. Another incentive was the stimulating scientific environment, not only for doctoral students and other collaborators but also for senior researchers, even though some of them had first to discover this potentiality. The growing success of LIVES brought a parallel rise in the scientific prestige of being associated with it.

The initial leadership team already had some experience in interdisciplinary collaboration. At the start of the program, however, they were still rather junior. As they were trying to mobilize senior people, they faced status and power differences. The presence of two senior Swiss members (de Ribaupierre and Levy) on the scientific advisory committee was helpful in this situation, and the committee worked in ways that supported the co-directors. This was especially useful when some IP projects needed to be eliminated.

Despite their geographical proximity, it was difficult to share resources between the two home institutions. This was not just because of their competitiveness but also because each institution has its own culture and needs. As noted earlier, universities in Switzerland are largely funded and run at the cantonal level. The contexts in which they operate and the resources they have at their disposal are thus dramatically different.

Doctoral education is a compulsory feature of all NCCRs. Like faculty, most of the doctoral students had training and were seeking degrees in single traditional disciplines. They faced tensions related to the need to design dissertation projects that would be approved in their departments and also conduct their research in the context of an interdisciplinary training program. In the first phase, students affiliated with LIVES did not receive any common training besides the orientation to the program upon their entry, consistent with Swiss doctoral programs. LIVES eventually required a certain number of seminars on topics of interest. In the second phase, a more focused curriculum was established to focus on theory and methods, also exposing students to the core concepts of “vulnerability” and “life course” and fostering the integration of these concepts in their research and emerging intellectual identities. Still, as evident in the annual Doctoriales (days where all students presented their research and received critical commentary from members of the advisory board and associated faculty), some students had difficulty articulating how their projects related to these concepts, despite the efforts of the faculty to inculcate them into students’ research.

Going Forward

As the chapters of this book reveal, LIVES has concentrated its efforts on understanding vulnerability in middle and later adulthood, and on the expression of vulnerability through stressors, resources, and reserves. It has asked pressing questions about, and gathered precious longitudinal data on, a variety of topics, including second-generation migrants’ and young adults’ transition to adulthood; parenthood, couple, family experiences in the early decades of adult life; work, family, and leisure in midlife; and professional careers and aging. There are many questions to continue asking about other populations and topics in adulthood, and many questions to be asked about populations and topics in the earliest years of life (infancy, childhood, and youth) as well as in the latest years. There is also a need to focus on specific groups in settings of vulnerability, such as people who are refugees, imprisoned, or without housing. LIVES has involved study participants in vulnerable groups such as women with AIDS or breast cancer, people with significant health incidents, or who are divorced, bereaved, single, or unemployed. Naturally, populations that are hardest to reach were underrepresented in the earlier studies and outreach efforts of the LIVES program. This is now one of the current directions of the program.

There is continued work to do in evolving the concept of vulnerability. Vulnerability is a relatively recent term, one that has even grown in the last two years amid the COVID-19 pandemic and the inequalities and social strife it has exposed or brought in its path. A proposal today to study vulnerability in a life course perspective would be even more attractive than it was a dozen years ago when LIVES began charting this territory. The next frontier of research will need to advance the rigor of the concept and associated theories. Its primary strength is also its primary weakness: It is a broad term that can hold many other concepts within or alongside it. For example, much remains to be clarified about how vulnerability articulates with longstanding or new discussions of coping, adaptation, resilience, risk, precarity, adversity, uncertainty, instability, and the like. This demands not only greater conceptual clarity regarding the distinctions between vulnerability and these overlapping or adjacent concepts, but also their assessment.

Both within and outside of the LIVES program, there is a need to develop and validate more sophisticated measures of vulnerability that are also sensitive enough to capture changes in its core components: “stressors,” “resources,” and “reserves” (the latter of which recently emerged in their framework) and to demonstrate their interrelationships. In particular, the concepts of resources and reserves have a long history in child developmental psychology (e.g., Vygotsky’s [1930–1934/1978] zone of proximal development) and lifespan developmental psychology (e.g., Baltes’ [1987] notions of selective optimization and compensation), are primed for new exploration. These concepts are particularly important in contemporary times, amid the COVID-19 pandemic and rampant civil and political unrest that has placed extraordinary demands on individuals.

The component of “reserves” is a good place to begin clearer exposition, including what it is, what its forms are, and how it interacts or overlaps with “resources” in relation to vulnerability. Reserves will also need to be better articulated in relation to other traditions in the social and psychological sciences. For example, the notion of “social reserves” seems aligned with traditional sociological concepts such as social capital and social integration, and “cognitive reserves” has long been present in lifespan psychology and neuroscience. As it is now being used, “reserves” largely seems to be understood as distinct from “resources” but at times seems to be used interchangeably with it. The notion of “dormant resources” also sounds like a reserve, something akin to “being ready” for action rather than action itself. There is not yet consensus about these terms and their usage, and “reserve” has not yet been threaded throughout the larger LIVES portfolio but has emerged in a few of the projects in the final phase (e.g., on family and social relationships; cognitive functioning). These directions are ripe for conceptual and theoretical development.

Viewed in a life course perspective, much remains to be learned about how the forms of vulnerability and their sources and consequences might be distinct in particular periods of life (e.g., for children, teens, young adults, those in midlife, or those in the early and later phases of old age). That is, there is a need for more systematic comparative research across age groups and life phases, and to understand how age and aging matter in relation to vulnerability. Importantly, there are significant leaps to make with respect to specificity: under what conditions does vulnerability matter (or not), for whom, when, and how. It is similarly important to understand what these things mean for families and societies when they are considered in aggregate, from the vantage points of whole groups and populations. At an even higher level, there is much to be learned about vulnerability as a basic and universal human experience that transcends times and places.

An examination of vulnerability in relation to life course dynamics demands longitudinal inquiry and data, although it is highly unusual to have reasonable indicators of stressors, resources, and reserves, let alone comprehensive measures of these things, over long periods of time. These will continue to represent major challenges for the field. Methods can also help bridge conceptual gaps; a common methodological approach can help when there is no agreement on concepts. Over time, the participants in LIVES moved toward a more integrated view of methods, seeing them more fluidly and developing greater appreciation for methods other than those that might have been championed in the beginning. Appreciation also grew around mixed-methods strategies that combined various quantitative and qualitative approaches. As the chapters of this book illustrate, gains have been made with respect to harnessing multiple methods to reveal vulnerability processes within the context of life-course dynamics, including major advances in developing and analyzing life calendars, gathering data on hard-to-reach populations, and combining event history and sequence analysis as well as longitudinal and survival methods.

Because vulnerability occurs in the social world, LIVES has pointed to the need to examine how social processes generate and perpetuate inequalities and how policies and practices can counteract inequalities and offset vulnerabilities as people grow up and older. The program has reinforced the need to develop life-course policies that focus on supporting individuals when they go through key life transitions and to generate life-course sensitivities in street-level bureaucrats and political leaders. So, too, has the program emphasized the importance of elucidating how an array of external conditions—from larger historical, economic, and political environments all the way down to local environments, like communities and neighborhoods and family environments—matter in creating and responding to vulnerability throughout the life course.

Conclusion

Some powerful messages are emerging from the findings of LIVES program: The crude and constant divide often made between the “haves” and “have-nots” should be replaced by a process-oriented (life course) perspective in which vulnerability is not a persistent or permanent condition but is rather a dormant condition of the social actor, activated in specific situations and contexts. What are often viewed as permanent states in people and populations are highly variable as the result of these specific situations and contexts. Their findings call into question pervasive assumptions about the linear accumulation of disadvantage over the life course and instead reveal how early hardships are coupled with lifelong compensation processes. Stressful life events and transitions may shock the life trajectories of individuals, but these shocks are more detrimental to people who have fewer resources or reserves. And yet, over time, people do tend toward adaptation or recovery, aided by resources and reserves in themselves and in their environments—which become prime targets for interventions to reduce vulnerability. In probing gender, the program has also revealed how gender inequalities are not necessarily the direct effect of stereotyping and institutional discrimination but are instead fueled by social processes that unfold in relation to life transitions (e.g., becoming parents, divorcing, changing jobs, caring for others).

A test of an NCCR is whether a topic is important enough to become a goal of its institutions. This is being realized now, particularly through the launch of a new permanent center: “LIVES—Swiss Center of Expertise in Life Course Research” (“Vision of LIVES: An Integrated Theoretical Concept”). An even greater test of the success of an NCCR is whether it has transformed its intended fields and had international impact. Strong interdisciplinary research takes time to conduct—and time to wield its influence. In the dozen years of this grand experiment, there have been many successes and it has been our deep pleasure and honor to have made the journey alongside this extraordinary team of scholars. It is with great anticipation that we watch its evolution and await its cumulative scientific and social returns.

References

Baltes, P. B. (1987). Theoretical propositions of life-span developmental psychology: On the dynamics between growth and decline. Developmental Psychology, 23(5), 611–626.

Spini, D., Bernardi, L., & Oris, M. (2017). Toward a life course framework for studying vulnerability. Research in Human Development, 14, 5–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427609.2016.1268892

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes (M. Cole, V. John-Steiner, S. Scribner, & E. Souberman, Eds.) (A. R. Luria, M. Lopez-Morillas, & M. Cole [with J. V. Wertsch], Trans.). Harvard University Press. (Original manuscripts [ca. 1930–1934])

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Settersten, R.A. et al. (2023). Overcoming Vulnerability in the Life Course—Reflections on a Research Program. In: Spini, D., Widmer, E. (eds) Withstanding Vulnerability throughout Adult Life. Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-4567-0_26

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-4567-0_26

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-19-4566-3

Online ISBN: 978-981-19-4567-0

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)