Abstract

This chapter emphasize several dimensions of resources as reserves. Lifelong dynamics are crucial for the understanding of vulnerability development across adulthood. The chapters of this section all contribute empirically to the understanding of resource dynamics through the life course. They tackle important issues regarding long-term processes of resilience and vulnerability. They show the importance of developing a lifelong perspective on resources when dealing with various outcomes (i.e., health, well-being, income, social capital). The contributions highlight the existence of a diversity of individual reserves to avoid or deal with critical events. This diversity refers to various levels: micro (e.g., educational, psycho-social), meso (e.g. relational) and macro (e.g. social policies). The systematic accumulation of (dis)advantages across life course is questioned, and, conversely, the existence of individual reserves making dynamics of resilience for more vulnerable individuals possible. The impact of socio-historical contexts on reserve dynamics will be considered, enabling the consideration of historical time as a critical factor stressed by the life course paradigm.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Research on human development has stressed the importance of resources to account for the multifaceted nature of ontogenesis. Resources are at the cornerstone of the processes implied by individuals coping with ‘life changes’, whether positive or negative, such as stressful life transitions, adverse events, and hazards. Resources have been conceptualised by former publications, especially in sociology and economics, in reference to various forms of ‘capital’ (Bourdieu, 1985; Dannefer, 2003; O’Rand, 2006). While the focus on capital has helped sensitise scholars to the importance of resources for developmental outcomes, such discussion has remained focused on the unequal acquisition of advantages and positive development over life and has somewhat disregarded the protective function of resources. It has also largely conceptualised temporal processes in terms of the continuous accumulation of advantages or disadvantages (DiPrete & Eirich, 2006). An alternative concept may provide a complementary look at the factors that enable individuals and societies to overcome vulnerability in life trajectories. This section of the book has proposed a variety of empirical results that support a reserve perspective on vulnerability in the life course. This chapter briefly summarizes some critical results of this section, illustrating the potential of the reserve perspective for life course research.

The Reserve Perspective

Originally, reserves were defined in relation to protection granted by resources against clinical manifestations of neurological damage. In the field of ageing, the notion of cognitive reserve has been developed to support the hypothesis that cognitively stimulating activities in childhood and young adulthood and across the life course will contribute to maintaining or improving cognitive functioning and delay its decline in older age (see also the chapter by Ihle et al.). One remarkable example is the Nun study, in which older individuals were observed to demonstrate perfectly (age-adequate) independent everyday functioning despite their brains showing severe evidence of neurological signs of Alzheimer’s disease (Riley et al., 2005). Their cognitive reserve somehow protected these individuals from being affected in their outcome behaviour.

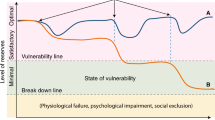

The dimensions and perspective proposed by such early work on reserves in the field of neuroscience and ageing can be extended to resources beyond cognitive decline to critical life domains such as psychological traits, education, health, family and social integration. The concept of reserves adds to the literature on vulnerability over the life course a systematic consideration of the time span or dynamic dimension of resources, either in their constitution or their depletion, as well as the presence of resource thresholds below which individuals cannot function at societal standards. It also stresses that resources have a protective function against life hazards and thus should not only be interpreted as pathways to productive investments. The reserve perspective argues that human development implies the formation, activation, maintenance and reactivation of resources over the life course, be they biological, physiological, cognitive, emotional, economic or relational (Cullati et al., 2018). ‘Reserves’ refers to means that are not needed for immediate use but that, when accumulated in sufficient manner, help individuals weather shocks and adversity and that delay or modify the processes of decline in well-being, health, wealth and social life throughout ageing. In other words, reserves are resources that have been sufficiently accumulated across the life course and are available when facing life shocks and adversity, social or economic stressors, or periods of collective or individual stress (Cullati et al., 2018). With respect to vulnerability, defined in life course studies as a lack of resources that makes it more likely that critical events will occur and more difficult to recover from such events (Spini et al., 2017), reserve constitution and activation represent the protective dimension of this process; in other words, the dynamics that contribute to avoiding, coping with or recovering from various stressors.

To summarise, four temporal dimensions are considered paramount in the reserve perspective: their build-up, their activation and depletion in the face of a critical life event, and their potential replenishment in the months or years following that event. Several processes are relevant: First, reserves are resources that take time to accumulate and therefore should not be spent in daily life. Second, a low level of reserves weakens individuals’ ability to adapt to life changes and shocks. Below a certain threshold, returning to a functional level of reserves is unlikely, if not impossible, due to the processes of accumulating disadvantage (Dannefer et al., 2018).

The Importance of Reserves

Chapters in this section have stressed the importance of reserve constitution and reconstitution in addressing vulnerability issues. The chapter by Ihle and colleagues based on VLV data showed the direct association between cognitive health in old age and cognitive and relational reserves constructed at early stages of the life course, especially through the practice of leisure activities. The authors highlighted the processual constitution of cognitive reserves across the life course, which surpasses the influence of initial cognitive performance on cognitive health later in life. It is important to stress that the impact of processual factors on cognitive ability in old age is stronger in the case of initially disadvantaged individuals, who had low educational and professional capacities in midlife. Although the results showed that social characteristics, such as sex, age and educational level, were associated with limits on the accumulation of relational and cognitive reserves over time, the agency of individuals remains important for the constitution of such reserves. One important finding revealed the reciprocal link between cognitive and relational reserves, which do not follow the same pace in their constitution but nevertheless interact to limit cognitive decline in old age.

The chapter by Oris et al. showed that the constitution of economic and social reserves has been strongly unequal for the cohort reaching old age in the 2010s, as it depended heavily on individuals’ initial social characteristics. Those with a lower level of education have had fewer chances to occupy advantageous social positions and be part of generous pension schemes than individuals who had higher levels of education. Accordingly, the former have quickly exhausted their economic reserves after the transition to retirement. Similarly, highly educated older adults appear to have developed and maintained a more diverse set of relational reserves, including in their personal networks not only family members but also friends as well as members of associations (Baeriswyl, 2017). These results stressed the interrelation of education, economic, and social reserves. Interestingly, Oris et al. also stressed that intergenerational financial transfers constitute a main depletion of economic reserves among old adults. Consequently, such transfers provide unequal access to the accumulation of financial reserves by individuals from the younger generation. Such an inequality is an example of the spillover effects among various reserve sets and an illustration of the linked lives principle (Elder, 1995).

The study by Cullati and colleagues confirmed the impact of social stratification on reserve constitution by showing that childhood socioeconomic disadvantages were associated with consequent problems in functional and mental health in older age. In particular, the decline in mental and physical health in old age was strongly associated with the cultural reserves accumulated during childhood, as revealed by the number of books available in the parental household. Thus, the initial lack of cultural reserves in early childhood could be critical for health problems in later adulthood, and it is difficult for social benefits to correct this deficit over time. Furthermore, Culatti et al. stressed the gender-biased impact of reserves on these subjective health trajectories. Indeed, some acquired benefits, such as the level of education or successful professional careers, mitigated the lack of initial reserves for men but not for women. This gender-biased impact of childhood reserves on health in later adulthood was accounted for by the limited access to education and professional careers for women of the generations considered in the study.

The chapter by Gauthier and Aeby focused on the processual perspective of reserves accumulation and critically examined the timing and chronological order of life events that are linked in typical patterns, which LIVES research has greatly contributed to discovering (see Chapter by Studer & Gauthier). The constitution of educational, financial and relational reserves depends on processual factors that unfold over time, such as the possibility for individuals to remain in full-time employment throughout their careers, the presence of a stable partnership (as indicated by marriage) or the number of parenthood experiences that one has had. As in Oris’s and Cullati’s chapters, however, initial social characteristics, such as nationality, country of origin and sex, were shown to exert a strong impact on reserves constitution. An unstandardised trajectory with an early transition from low vocational education to employment or periods of unemployment stems from a migration background, especially from low-skilled migration countries, for young adults. Females more than males show limited educational reserves, with subsequently more unstable professional trajectories that are characterised by more interruptions in full-time employment, part-time employment or unemployment after childbearing. Thus, the accumulation of educational, financial and relational reserves over the life course is highly unequal across individuals.

While those chapters stressed the links among various areas of reserves, and especially a lack of educational reserves implying decreasing levels of economic and relational reserves later in life, none of the chapters found strong evidence in support of the hypothesised systematic bias towards the accumulation of advantages and disadvantages across the life course or the fact that early interindividual differences increase over ageing (Dannefer, 2021). Cullati et al., for instance, stressed that individual health trajectories in different childhood socioeconomic groups ran mostly parallel throughout ageing; in other words, early differences in health problems did not increase over the life course due to unequal reserves constitution and activation. Similarly, Oris et al. preferred to use the term ‘cumulative continuity’, borrowed from Elder et al. (2015, p. 23), to summarise their results about the economic conditions of retired Swiss people and the long-term influence of the lack of educational reserves on the risk of precarity and poverty.

In particular, Oris et al. stressed that the accumulation of disadvantages and advantages is not symmetric because welfare regimes have helped limit the impact of the lack of reserves for the most disadvantaged. Indeed, insufficient accumulation of individual reserves can—to some extent—be compensated for by social policy programs, which may account for the minimal evidence supporting the thesis of disadvantage accumulation in LIVES research. For instance, concerning health inequalities, Cullati et al. stressed that a universalist welfare state, such as those found in northern countries, is particularly effective in mitigating the long-term impact of childhood disadvantages on health outcomes. Relational reserves, particularly family support, constitute another reserves area mentioned by both Oris et al. and Cullati et al. as an important resources pool to deal with ageing and eventually attenuate earlier disadvantages, particularly when welfare provisions away from this role.

The Active vs. Passive constitution of Reserves

Another critical dimension of reserves throughout the life course concerns their passive versus active acquisition. A passive model of reserves assumes that they are acquired by the action of others, generally early in life, and in line with social inequality. In contrast, an active model of reserves underlines that life trajectories may be altered through being activated by the personal agency of individuals as a capacity to invest in strategic activities over their life course. To some extent, such reserves can also be activated by external actors, and the literature suggests targeted interventions. The importance of stimulation to maintain functioning is a human process that is applicable to many life domains, such as cognitive functioning, but also to social interactions and participation in the labour market. The chapter by Rossier et al. showed that such agency, defined as individuals’ ability to actively constitute and reconstitute reserves, may be measured empirically, thereby suggesting that ‘adaptability’, as a kind of psychological reserve, is a key feature for career development. The main life transitions, such as the transition from education to employment, and the involuntary career changes associated with negative events such as accidents, health problems, or unemployment, are vulnerabilising experiences for career development and individual well-being. When individuals encounter such critical events, increased adaptability enables reserve reconstitution through psychosocial tools such as the ‘career adaptability’ tool for managing work-related tasks, traumas, and transitions. Adaptability can be considered an individual reserve that is ‘dormant’ in usual conditions but can be activated under the influence of stressful factors such as limited career opportunities and career changes. Adaptability becomes paramount in times of collective uncertainty and global turmoil.

Reserves Thresholds

A central dimension of the reserves concept is that it necessitates the consideration of functional thresholds. Reserves are sufficient if they help the individual (1) not experience a stressful event because they have sufficient resources to avoid exposure to it, such as when individuals use their social networks and reputation to obtain a new job right before being dismissed or to solve intimate issues and prevent divorce; (2) cope effectively with nonnormative stress, for instance, by using their social networks to support them when they become sick or to draw from their savings when they become unemployed; and (3) swiftly recover from the nonnormative event, for instance, by paying for advanced onerous medical treatment to recover or by moving out of their home in the case of family violence by paying for an expensive rental.

One critical finding by Cullati and colleagues in their chapter was that individuals who grew up in advantaged households had stronger declines in verbal fluency (an indicator of cognitive function) than disadvantaged participants, but this decline began at a later age and from a higher level of fluency. In other words, the threshold at which decline becomes apparent was reached at different ages, probably because the accumulated reserves made it possible for the advantaged to deal in their daily life with the shortcomings imposed by their cognitive decline.

Ihle and colleagues also showed that individuals with low educational resources at an early stage of their life course were more likely to benefit from late-life leisure activity engagement. Moreover, adequate cognitive functioning predicted a smaller subsequent decline in well-being only for young-old adults and not for the oldest adults. The authors stressed that as soon as individuals’ functional abilities break down and fall below a critical threshold, decline can no longer be compensated for because reserves are no longer effective. These results showed that thresholds may depend on individual positions within social structures and the life course, as such positions influence reserve composition. As such, thresholds also include gender issues, and indeed, thresholds for activating educational reserves in life appear to be higher for women. The chapter by Gauthier and Aeby stressed that women are globally at a disadvantage regarding their self-esteem trajectories, except for those who have a high vocational track. Oris et al. stressed that having a tertiary education is more determinant for older women’s propensity to access public participation, in particular activities involving decision making. Accumulating educational reserves thus appears especially important for women’s life course.

Period Effects

Because of the importance of historical influences on personal trajectories (e.g., Elder, 2018), reserves have a distinct set of attributes and meanings across historical periods. The chapter of Oris and colleagues revealed the crucial importance of cohorts to the constitution of reserves. Individuals in Switzerland born between 1911 and 1946 developed continuous occupational trajectories within a context of socioeconomic growth. At the same time, the development of a retirement system—based on standardised occupational trajectories (Kohli, 2007)—institutionalised the constitution of a certain amount of economic reserves to secure material conditions in older age. Greater access to higher education and its influence on individual careers tend to explain the decrease in poverty in old age. In these cohorts, more generally, educational reserve and resulting occupational trajectories also offered access to middle-class lifestyles associated with the institution of the nuclear family, which constituted the main relational reserves in this period (Rusterholz, 2017; Segalen, 1981). However, these trajectories also relied on a gendered model of labour division according to which men were the only breadwinners and women were the housekeepers. Thus, (married) women’s occupational trajectories were more likely to be shorter, interrupted and part-time employed compared to men, and women were mainly socioeconomically dependent on their husband’s reserves (education, income) in this very specific birth cohort. Individuals from previous and subsequent birth cohorts reached old age with very different prospects in terms of reserve acquisition and therefore faced different levels and types of vulnerability. In terms of economic situation in old age, for instance, the movement towards a greater destandardisation of the life course (Kohli, 2007)—involving, in particular, greater instability and plurality in family trajectories but also in occupational trajectories (see Chapter by Rossier et al.) and a decline in the gendered division of labour—have challenged the retirement system, which was built on the continuous and upward occupational trajectories of men and the stability of the nuclear family.

In addition to the issue of reserve constitution, historical context influences the activation of reserves across the life course. Indeed, for the cohorts mentioned above, nonnormative events were rare, and the activation of reserves accumulated over their standardised (and gendered) life course remained limited to a few, mainly normative transitions (education, adulthood, retirement). As stressed by Rossier et al., the destandardisation of occupational trajectories increases the number and complexity of transitions, the risk of marginalisation, and the importance of personal resources such as adaptability in facing such challenges. In other words, the destandardisation of the life course—which occurs in all areas (work, family) and stages (childhood, adulthood, old age) of the life course—tends to make the accumulation and activation of reserves particularly acute. In this context, the increasing role of individual agency in life course management refers to the importance of individual (or psychosocial) reserves such as adaptability (chapter by Rossier et al.) and to the constitution of educational, relational or economic reserves. Indeed, the constitution of such reserves has become less secured by the life course institutions (typically, the educational system, the nuclear family and the job market) and has been continuously challenged by increasing discontinuity and diversity, as shown by the longitudinal study of life trajectories (e.g., chapter by Gauthier & Aeby). For instance, education trajectories have become less linear and more individualised, which includes increasing breaks, discontinuities and possibilities of reorientation (Meyer, 2018), and lifelong learning has become crucial in educational reserve dynamics (i.e., constitution, maintenance, reconstitution) (chapter by Rossier et al.; see also Bertozzi et al. 2005; von Erlach, 2018).

Furthermore, the COVID-19 period has proven the importance of reserves in critical times. Indeed, it is in periods of collective crisis that the effect of reserves is the greatest, yet it is also in these periods that their accumulation becomes most problematic (Widmer, forthcoming). During the COVID-19 crisis period, many inequalities in the reserves available to individuals shaped their situations. A few such examples include the following: Some were able to rely on their villas or second homes, the results of the accumulation of economic reserves (sometimes over several generations), to escape the radical conditions of urban apartment confinement; others were able to mobilise their relational reserves to cope with illness or loneliness; some were able to invest their cultural reserves, accumulated during long studies, in home-schooling their children; others were able to rely on their employer’s loyalty to them, the logical outcome of stable and cumulative occupational trajectories. The fact remains that a large number of individuals, without reserves in any area, found themselves naked in the face of the vagaries of the crisis and dependent on social programs or private initiatives that were limited in both time and coverage. The effect of reserves will not end with the end of the health crisis. Individuals who have accumulated economic reserves (savings, property) in their previous trajectories will probably be able to cope better with the economic crisis that follows. Note that reserves can be individual or collective. Countries or regions may have accumulated reserves in various areas that made it easier to manage the crisis situation. Such a situation was observed during the pandemic period, when some countries had stocks of masks and respirators available as well as health systems capable of coping, while others found themselves partially or completely deprived. Obviously, this availability is related to the wealth of individuals and nations, but some countries or individuals may have many resources without necessarily having them as reserves, given the low stocks they have at their disposal. Typically, the health system of Switzerland is well-resourced, with excellent professional and medical devices. However, it has shown certain limits in terms of reserves during the COVID-19 pandemic, with intensive care units being quasi-saturated several times. The importance of reserves for coping with crises therefore concerns both individuals and the social systems of which they are part.

Conclusion

The chapters in this section have stressed the critical importance of reserves as deterrents of vulnerability checks over the life course. The LIVES theoretical model stresses that a reserves perspective on resources may help research move forward in understanding temporal processes associated with vulnerability issues. It should be noted that this perspective complements other understandings of the unfolding of social inequalities throughout life trajectories. For gender inequalities, the chapters in this section, for instance, showed that there is an ongoing process of economic reserves throughout career development that accounts for much of the difference in the economic vulnerability of men and women after retirement. Interestingly, childhood socioeconomic disadvantages were associated with problems in physical and mental health in later adulthood for women but not for men, whereas some leisure activity—in particular, the use of the internet—reduced cognitive decline in old age among men but not among women. Fascinating gendered processes occur throughout the life course that place individuals at risk later on by depleting the reserves available to them when life shocks happen, thereby making a recovery very unlikely for individuals from some social groups, whereas individuals from other groups may easily recuperate. Thresholds are important because they change individual agency and the response of institutions that deal with individual vulnerability. Such considerations are obviously especially important in historical periods of crisis, where the availability of collective support may be depleted, and the challenges facing individuals may be much greater than in peaceful times. In any case, there is a need for much more empirical research to be conducted in the future on the unfolding and use of resources over the life course and in specific locations. The reserves approach may obtain critical traction for understanding such issues in economies and societies in crisis.

References

Baeriswyl, M. (2017). Participations sociales au temps de la retraite. Une approche des inégalités et évolutions dans la vieillesse. In N. Burnay & C. Hummel (Eds.), L’impensé des classes sociales dans le processus de vieillissement (pp. 141–170). Peter Lang.

Bertozzi, F., Bonoli, G., & Gay-des-Combes, B. (2005). La réforme de l’État social en Suisse: Vieillissement, emploi, conflit travail-famille. Presses polytechniques et universitaires romandes.

Bourdieu, P. (1985). The forms of capital. In J. C. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education (pp. 241–258). Greenwood.

Cullati, S., Kliegel, M., & Widmer, E. (2018). Development of reserves over the life course and onset of vulnerability in later life. Nature Human Behaviour, 2(8), 551–558.

Dannefer, D. (2003). Cumulative advantage/disadvantage and the life course: Cross-fertilizing age and social science theory. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 58(6), S327–S337.

Dannefer, D. (2021). Age and the reach of sociological imagination: Power, ideology and the life course. Routledge.

Dannefer, D., Han, C., & Kelley, J. (2018). Beyond the “haves” and “have nots”. Generations: Journal of the American Society on Aging, 42(4), 42–49.

DiPrete, T. A., & Eirich, G. M. (2006). Cumulative advantage as a mechanism for inequality: A review of theorical and empirical developments. Annual Review of Sociology, 32, 271–297.

Elder, G. H. (1995). The life course paradigm: Social change and individual development. In P. Moen, G. H. Elder, & K. Luscher (Eds.), Examining lives in context. Perspectives on the ecology of human development (pp. 101–139). American Psychological Association.

Elder, G. H. (2018). Children of the great depression: Social change in life experience. Routledge.

Elder, G. H., Jr., Shanahan, M. J., & Jennings, J. H. (2015). Human development in time and place. In M. Bornstein & T. Leventhal (Eds.), Ecological settings and processes in developmental systems, Vol. 4 of R. M. Lerner (Ed.), The handbook of child psychology and developmental science. Wiley.

Kohli, M. (2007). The institutionalization of the life course: Looking back to look ahead. Research in Human Development, 4(3–4), 253–271.

Meyer, T. (2018). De l’école à l’âge adulte: Parcours de formation et d’emploi en Suisse. Social Change in Switzerland, 13. https://doi.org/10.22019/SC-2018-00001

O’Rand, A. M. (2006). Stratification and the life course: Life course capital, life course risks, and social inequality. In R. H. Binstock & L. K. George (Eds.), Handbook of aging and the social sciences (pp. 145–162). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012088388-2/50012-2

Riley, K. P., Snowdon, D. A., Desrosiers, M. F., & Markesbery, W. R. (2005). Early life linguistic ability, late life cognitive function, and neuropathology: Findings from the Nun Study. Neurobiology of Aging, 26(3), 341–347.

Rusterholz, C. (2017). Deux enfants c’est déjà pas mal. Famille et fécondité en Suisse (1955–1970). Antipodes.

Segalen, M. (1981). Sociologie de la famille. Colin.

Spini, D., Bernardi, L., & Oris, M. (2017). Toward a life course framework for studying vulnerability. Research in Human Development, 14(1), 5–25.

von Erlach, E. (2018). La formation tout au long de la vie en Suisse: Résultats du microrecensement formation de base et formation continue 2016. Office fédéral de la statistique (OFS). https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/fr/home/statistiques/education-science/formation-continue/population.assetdetail.5766408.html

Widmer, E. D. (forthcoming). COVID-19 ET développement des vulnérabilités: entre normes déroutantes et manque de réserves. In E. Rosenstein & S. Mimouni (Eds.), COVID-19 Tome II: Les politiques sociales à l’épreuve de la pandémie. Seismo. ISBN: 978-2-88351-107-1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Widmer, E.D., Baeriswyl, M., Ganjour, O. (2023). Synthesis: Overcoming Vulnerability? The Constitution and Activation of Reserves throughout Life Trajectories. In: Spini, D., Widmer, E. (eds) Withstanding Vulnerability throughout Adult Life. Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-4567-0_19

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-4567-0_19

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-19-4566-3

Online ISBN: 978-981-19-4567-0

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)