Abstract

This chapter presents the vulnerability framework used in the different sections chapters of this book. Vulnerability is defined as a process of resource loss in one or more life domains that threatens individuals in three major steps: (1) an inability to avoid individual, social or environmental stressors, (2) an inability to cope effectively with these stressors, and (3) an inability to recover from stressors or to take advantage of opportunities by a given deadline. The chapter also stresses the importance of resources, reserves and stressors to understand the dynamics of vulnerability throughout the life span. This life course perspective of vulnerability processes is better understood through three main perspectives: multidimensional (across life domains), multilevel (using micro, meso and macro perspectives) and multidirectional (the study of vulnerability life trajectories should envisage all possible directions, namely stability, decline, recovery, growth trajectories and in long-term). We also argue in this chapter that a vulnerability framework enables researcher to understand the craft of our lives and the responses, be they individual (through agency), collective (through support) or institutional (social policies) that can be given to life events, life transitions, and to the stressors that individuals inevitably face sooner or later in their life.

“The only choice we have as we mature is how we inhabit our vulnerability”

Vulnerability by David White

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Life course

- Vulnerability

- Resources

- Reserves

- Stressors

- Life domains

- Multilevel

- Life trajectories

- Agency

- Social support

- Social policies

This book is about vulnerability in the life course. The concept of vulnerability has been developed in the field of environmental sciences and has received growing attention in recent years in the social and psychological sciences (Forbes-Mewett, 2020; Misztal, 2012; Ranci, 2010; Schröder-Butterfill & Marianti, 2006). This success is due to various trends, such as the generalization of collective risks (including pandemics, armed conflicts and their aftermath, mass unemployment, volatility in stock markets, and issues associated with climate change), a process of individualization of life trajectories (Kohli, 2007), and societal changes from a society of acquisition to a society of risks and uncertainties concerning, notably, family and professional life (Sapin et al., 2007). Thanks to the LIVES programme, for twelve years, a large network of researchers from sociology, psychology, demography and economics have worked together in Switzerland on the issue of vulnerability, believing that joint interdisciplinary work sensitive to processes unfolding throughout life trajectories was worth consideration in research dealing with vulnerability issues. This book summarizes some of the most intriguing results of this collective scientific endeavour and, as such, constitutes an entry point to the variety of results, methods and data that have been generated by the National Centre of Competence in Research (NCCR) LIVES programme and later by the Centre LIVES (see Appendix 2 for a brief institutional history of the centre).

Before entering the various domains and issues related to vulnerability, this introduction defines what is meant by vulnerability from a life course perspective. It stresses the importance of the dynamics existing between resources and stressors. It describes three interrelated life course principles, which enable the multiple analysis of these complex dynamics: the multidimensional, the multilevel, and the multidirectional perspectives (Spini et al., 2017). Each of these dimensions is considered separately in its own part of the book (Bolano & Bernardi; Spini & Vacchiano; Widmer, Baeriswyl, this book), and the results are then summarized in a concluding chapter. The fourth part of the book presents the advances in methods to approaching vulnerability from a life course perspective. Finally, an international group of scholars (see chapter Settersten et al., this book) who were members of the LIVES International Advisory Board shares some thoughtful perspectives inspired by the LIVES vulnerability framework.

A Life Course Definition of Vulnerability

We find two contrasting and complementary views on vulnerability as a central feature of the life course in the literature (Brown, 2011): Vulnerability characterizes individuals and groups or categories who need care or the support of the welfare state, and vulnerability as an ontological and inevitable feature of the human condition throughout the life course. The first approach refers to a classic and rather static view of vulnerability as a syndrome, as a lasting state of dependence or lack of autonomy related to a need for others’ care to adapt (Misztal, 2012). This perspective has been echoed by many journalists, policymakers, physicians, social workers, and local authorities. It implies a state of weakness, inability, dependency (upon others and institutions) and the need to avoid harm and achieve adequate satisfaction of legitimate claims (Tavaglione et al., 2015). Typical social categories that are labelled vulnerable in this perspective include homeless people, sex workers, asylum seekers, refugees, children and the very old, the poor and those who are chronically ill, and, more generally, all groups that are frequently stereotyped as the least competent in society (Fiske et al., 2002). Interestingly, main criticisms in the social sciences have warned that this “needy” approach risks instrumentalising vulnerability as (1) a paternalistic and oppressive idea, (2) a mechanism of widening control, and (3) a reason to exclude or stigmatize groups or individuals (Brown, 2011, p. 316).

A second approach is rooted in political and moral philosophy (Anderson & Honneth, 2005; Macintyre, 1999; Turner, 2006). In this line of thought, vulnerability lies at the heart of social citizenship and human rights and is viewed as part of the personal and contextual circumstances in which individuals find themselves at different points in their lives. Life course studies, we think, as they are interested in individuals’ trajectories across the years, stress the idea of diverse, multidirectional trajectories in which vulnerabilty may unfold at various times and in various ways. Gains and losses occur throughout the entire lifespan (Baltes et al., 1998). Even though individuals may exert their agency and “follow the rules”, external social constraints and critical life events may lead them towards insecurity and loss of control over their own lives (see Widmer & Spini, 2017). The empirical research presented in this book indeed considers vulnerability as a central feature of an individual’s life and proposes a definition of vulnerability that can be shared and studied in social and psychological sciences from a life course perspective. In this regard, all human beings are stressed as having a latent vulnerability, which professionals or institutions may in specific situations objectify through diagnostics and other evaluative tools (Spini, 2012). Accordingly, the LIVES research project has contributed to developing an interdisciplinary space in which vulnerability processes can be studied empirically, proposing the creation of an approach bridging psychosocioeconomic vulnerability policy traditions and the life course perspective (Spini et al., 2017).

This approach, pluri- or interdisciplinary, features different advantages over previous approaches to vulnerability. First, it enables researchers from different disciplinary horizons to work together. This is not an easy task, as the issues considered relevant, as well as the concepts considered central and some of the empirical methods considered up to date, are not shared across the social sciences. A literature review by Hanappi et al. (2014) confirms that sociological studies for the most part focus on issues such as the impact on life trajectories of welfare states, poverty or family, whereas psychology focuses on issues related to personality, coping, stress and depression. Gerontology often focuses on frailty and issues related to health, which are much more limited in scope than vulnerability as a process that can evolve across different life domains. From this literature review, we hold that vulnerability is independent of these disciplinary focuses and a possible candidate for the integration of various phenomena across the social sciences. Indeed, a second advantage of relating the life course tradition and vulnerability as an ontological feature of the human experience is that it brings together knowledge of processes that can be generalized across lifespan psychology and life course sociology perspectives (Settersten, 2009) and topical fields such as health, family, work, and geographical mobility. Studying vulnerability from a life course perspective will not replace the precision of studies in these specialized fields, but it helps researchers develop elements of a metatheory (Overton, 2013) of vulnerability processes in the life course. Finally, we feel that the life course tradition could benefit from a framework such as that proposed in this book, not only for analysing the complexity of life trajectories but also for linking them to sociopolitical issues and seeking to increase individuals’ autonomy and well-being.

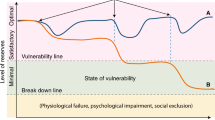

From this perspective, vulnerability is defined as a process of resource loss in one or more life domains that threatens individuals in three major steps: (1) an inability to avoid individual, social or environmental stressors, (2) an inability to cope effectively with these stressors, and (3) an inability to recover from stressors or to take advantage of opportunities by a given deadline (Spini et al., 2017). Several refinements need to be stated here.

First, the basic components of vulnerability processes are related to the dynamics of resources and stressors. Resources relate in a larger sense to whatever increases the likelihood of individuals meeting social expectations (including their own) or to elements that enhance individuals’ physical, mental or social functioning and health. In that regard, many individual factors, from personality traits, cognitive performance, and social or cultural capital to economic assets, can be considered resources. Notably, the concept of resources does not suggest some precise time-related process by which vulnerability can unfold or, to the contrary, be brought under control. In that respect, the conceptual and empirical advances enabled by the reserve perspective, as first developed in the neurosciences, is relevant for the study of vulnerability processes, as we shall see in Part III of this book. Reserves are dormant resources that are not needed for immediate use but that, when accumulated to a sufficient extent, are available for recovering from life shocks and adversity, social or economic stressors, or non-normative transitory periods across the life course (Cullati et al., 2019). Conversely, the notion of reserves implies that, below a certain threshold, individuals lose their capacity to adapt to stressors. Reserves are buffers against vulnerability processes and foster resilience (Cullati et al., 2019; Spini et al., 2017). Stressors are a central dimension of life events and lifespan losses from a psychological perspective (Reese & Smyer, 1983). However, stress is not only an individual subjective appraisal issue. Following Pearlin and his associates (Pearlin, 1989; Pearlin & Skaff, 1996), stressors are unequally distributed across the social spectrum. People in disadvantaged positions encounter more risks in experiencing stressors, notably chronic or strains and sudden stressors, precisely because they lack resources. Indeed, the relationship among health problems, stressors, and social status has been well established (Aneshensel, 1992; Thoits, 2010).

Second, there is a sequential dimension of vulnerability that unfolds in three consecutive steps: before the stressor, during the exposure to the stressors (notably, acute ones), and after the stressor happened. Defining vulnerability as a process rather than a state offers the advantage of distinguishing and combining different hypotheses, notably, the hypotheses of social causation and differential vulnerability (Diderichsen et al., 2019; Kessler, 1979). The hypothesis of social causation states that distal or proximal social statuses has an effect on subsequent states in other domains (notably health) and life course trajectories. The differential vulnerability hypothesis states that individuals with lower levels of personal or social resources may experience a greater susceptibility to harm when confronted with stressors than less vulnerable individuals. As social causation may be active since the start of life and in step 1 of the processual framework that we propose (and that can be measured by the direct effects of social categories, or levels of personal resources, on risks of being exposed to stressors), vulnerability susceptibility may be more observable in relation to specific stressors at step two or three of this sequential model.

Most empirical studies related to this sequential model have focused on the negative side of vulnerability. However, as George (2003) stresses, the inverse hypothesis that experiencing stressors may be a source of learning and increased resilience should not be hastily dismissed. It is important to consider opportunities and protective factors in each situation, not only constraints and stressors (Ferraro & Shippee, 2009). This approach suggests that vulnerability refers not only to the negative consequences of stressors or a lack of resources and reserves but also to the parallel processes of reserve constitution or reconstitution, resilience or recovery. As proposed by the relational perspective of Overton (2013), vulnerability must be placed in relation to its antonyms and should not simply be opposed to them. A difficulty of this approach, then, is to select a single antonym. The concept of invulnerability is not applicable to mortal human beings. However, there are candidates from different fields for juxtaposition with vulnerability in the literature, including autonomy (opposed to dependence in social policy or gerontology), resilience (versus chronicity, depression or vulnerability in PTSD and clinical literature), or robustness (versus frailty in gerontology). This relative fuzziness may be the subject of criticism by some, whereas others, such as Overton (2013), would probably defend the idea that concepts such as vulnerability and its antonyms should create spaces where “foundations are groundings, not bedrocks of certainty, and analysis is about creating categories, not about cutting nature as its joints” (p. 42). This is where we stand in this book.

Three Life Course Principles for Vulnerability Research

Vulnerability is molded by and a major entry into life course complexity in multiple domains in interaction through time. In this regard, life course research has made major advances in recent decades (Mortimer & Shanahan, 2003; Sapin et al., 2007; Settersten, Settersten Jr, 2003). Based on the founding principles and formational studies of several key scientists active in the life course and lifespan domain, such as Glen Elder, Jr., in sociology (see Marshall & Mueller, 2003) and Baltes and colleagues in psychology (Baltes et al., 1998), three main life course principles of vulnerability have framed the contributions to this book: multidimensional, multidirectional, and multilevel (Spini et al., 2017). Let us briefly describe these three dimensions, to which we will return in the empirical chapters.

Multidimensionality informs us about the life domain(s) or life spheres—i.e., family, work, health—that interact while shaping the individual’s life chances. Vulnerable states and vulnerability dynamics can be observed in and across all these dimensions. Within domains, stressors (life events, traumas, accidents, transitions or turning points) and resources such as wealth, education, and social capital are at play, and individuals must cope with these resources when facing stressors. Maintaining focus on this multidimensionality of the life course is necessary, as considerable empirical evidence exists that life domains interact with each other, as we shall see in the first part of this book (Bernardi et al., 2019). The research of Schüttengruber and colleagues (this book) is a good example of conflicts and synergies between life domains. The interdependence among life domains and the stress that they engender throughout adulthood is strongly related to social inequality and, especially, to gender issues (see Levy & Widmer, 2013). Of major interest here is how individuals use their reserves in various life domains to cope with difficulties and to take advantage of new opportunities.

The second principle stresses that vulnerability unfolds at various levels from the micro (personality traits, individual agency, daily interactions, etc.) to the macro (social policies, institutions, shared social norms or values). Thus, Part II of this book advances our understanding of vulnerability processes at the micro, meso and macro levels. The idea that the life course is played out by individuals within social structures is a central idea that applies to vulnerability. For example, the social stress model insists upon the importance of personal coping resources, such as control beliefs, and upon the continuous structural effects on chronic stress and health (Aneshensel, 1992). At the micro level, Bernardi et al. (2019) suggest considering infra-individual programmed factors such as the genome, which may exert an enduring impact on vulnerability processes. However, in this book, we do not consider these genetic influences, instead focusing on the psychological and social roots of vulnerability at different levels, including original attention to the meso-level mechanisms of vulnerability associated with groups, social categories, neighborhoods and networks (Vacchiano & Spini, 2021). This focus on the meso level fills an important gap between the micro and macro levels and resonates with the fundamental life course principle of “linked lives” introduced by Elder (1974/, 1995). This principle is particularly important when studying vulnerability for different reasons, notably the relationship between vulnerability and the need for others’ care (Misztal, 2012). Vulnerability is not simply individual, as it also impacts close ones, who amplify, share or suppress the effects of stressors and who bring or share needed resources. Social relationships lie at the heart of vulnerability and have an ambivalent role, as relationships with family members, for example, can be both main stressors and main resources related to vulnerability (Sapin et al., 2016). In summary, vulnerability unfolds simultaneously at various interrelated levels in need of articulation (Doise, 1986).

The multidirectional principle draws attention to the temporal dimension and multiple trajectories leading to unequal levels of vulnerability. Previous research stemming from the cumulative disadvantage paradigm has stressed an increasing divergence of life chances across the life course due to micro advantages that promote those better off at each transition of the life course (Dannefer, 2003; Merton). Building on this approach, the chapters in this section stress the critical importance not only of reserves built up over time but also of reserve activation when facing critical events and transitions and of reserve reconstitution after the occurrence of such events (Cullati et al., 2019). Reserves as resources stored for later use concern a variety of domains (work and educational skills, social capital, psychological competencies, economic assets and savings) and a variety of levels (from the individual up to the social system). Therefore, the third section provides an understanding of how the mechanisms uncovered in the two previous sections of the book play out over time and helps imagine solutions by which vulnerability can be dealt with at all levels.

Vulnerability: A Sensitizing Concept for Life Course Research and Social Policies

The study of vulnerability processes throughout the life course calls for an interdisciplinary approach, for methods sensitive to processes, and for adapted policies to sustain individuals across their life course. To understand the complex dynamics of stressors and resources implied by vulnerability processes, longitudinal studies appear to be the most suited methods from a life course interdisciplinary approach (Spini et al., 2016). Methods are shared tools that different disciplines can use (Tobi & Kampen, 2018). Interestingly, despite their common interest in life course processes, sociologists, psychologists, economists and demographers often use distinct quantitative and qualitative methods. To compensate for this trend, the fourth part of this book proposes some critical methodological advances that will help researchers address vulnerability in interdisciplinary work.

We chose vulnerability throughout adulthood as a central concern, along with the related processes of resilience, robustness, autonomy, or growth. We co-constructed the vulnerability sequential model with its main elements: stressors, resources and reserves (Cullati et al., 2019; Spini et al., 2017). Such a focus was not easy to reach, but theoretical interdisciplinarity was indeed achieved through the selected cross-cutting multidimensionality, multilevel, multidirectional, and methodological principles. This book presents these achievements and is organized along these four organizing principles of our life course perspective.

This book’s division into four parts is somewhat artificial. One of the main lessons emerging from these chapters is the interdependencies that exist among the multidimensional, multilevel and multidirectional principles, as also underlined by Bernardi et al. (2019). Considering these three life course principles together has not been fully achieved in our research program. However, as an apeirogon, the complexity of vulnerability during the life course is such that it is doubtful that any single course of research could fully account for it. Moreover, it is equally difficult to separate one of these principles from the others. Most chapters of this book, even though placed within a specific part, also often refer to the other principles. This is a strength of the life course framework shared throughout this book, which enables LIVES research to grasp some of the basic principles of vulnerability processes.

Finally, an important goal of research on vulnerability from a life course perspective is to achieve relevance and usefulness for civil society and decision-makers. Individual life trajectories are more uncertain with the spread of new as well as old social risks (Bonoli, 2005; Spini et al., 2017): Spillover effects of stress between work and family life, lack of resources in lone parenthood, long-term unemployment, being part of the working poor, or having insufficient social security coverage concern a growing number of individuals. The increase in contexts of collective vulnerability following COVID-19 or in relation to the climate or migration crises has huge effects on individual trajectories, notably those coming from the most vulnerable groups (see Settersten Jr. et al., 2020). It is hoped that this book will help the reader consider chains of interrelated factors that unfold in life trajectories, from personality traits to social policies. Such chains obviously need to be considered when making informed decisions about individual vulnerability in context.

References

Anderson, J., & Honneth, A. (2005). Autonomy, vulnerability, recognition, and justice. In J. Anderson & J. Christman (Eds.), Autonomy and the challenges to liberalism: New essays (pp. 127–149). Cambridge University Press.

Aneshensel, C. S. (1992). Social stress: Theory and research. Annual Review of Sociology, 18(1), 15–38. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.so.18.080192.000311

Baltes, P. B., Lindenberger, U., & Staudinger, U. M. (1998). Lifespan theory in developmental psychology. In W. Damon & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology (5th ed., Vol. 1: Theoretical models of human development, pp. 1027–1143). Wiley.

Bernardi, L., Huinink, J., & Settersten, R. A. (2019). The life course cube: A tool for studying lives. Advances in Life Course Research, 41, 100258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcr.2018.11.004

Bonoli, G. (2005). The politics of the new social policies: Providing coverage against new social risks in mature welfare states. Policy and Politics, 33(3), 431–449.

Brown, K. (2011). ‘Vulnerability’: Handle with care. Ethics and Social Welfare, 5(3), 313–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/17496535.2011.597165

Cullati, S., Kliegel, M., & Widmer, E. (2019). Development of reserves over the life course and onset of vulnerability in later life. Nature Human Behaviour, 2(8), 551–558. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-018-0395-3

Dannefer, D. (2003). Cumulative advantage/disadvantage and the life course: Cross-fertilizing age and social science theory. Journals of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 58B(6), S327–S337.

Diderichsen, F., Hallqvist, J., & Whitehead, M. (2019). Differential vulnerability and susceptibility: How to make use of recent development in our understanding of mediation and interaction to tackle health inequalities. International Journal of Epidemiology, 48(1), 268–274. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyy167

Doise, W. (1986). Levels of explanation in social psychology. Cambridge University Press.

Elder, G. H. J. (1974/1999). Children of the great depression (25th anniversary edition ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Ferraro, K. F., & Shippee, T. P. (2009). Ageing and cumulative inequality: How does inequality get under the skin. The Gerontologist, 49(3), 333–343.

Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J. C., Glick, P., & Xu, J. (2002). A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Competence and warmth, respectively follow from perceived status and competition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(6), 878–902.

Forbes-Mewett, H. (Ed.). (2020). Vulnerability in a mobile world. Emerald Publishing.

George, L. K. (2003). What life course perspectives offer to the study of ageing and health? In R. A. Settersten Jr. (Ed.), Invitation to the life course. Towards new understanding of later life (pp. 161–188). Baywood.

Hanappi, D., Bernardi, L., & Spini, D. (2014). Vulnerability as a heuristic for interdisciplinary research: Assessing the thematic and methodological structure of empirical life-course studies. Longitudinal and Life Course Studies. An International Journal, 6(1), 59–87.

Kessler, R. C. (1979). A strategy for studying differential vulnerability to the psychological consequences of stress. Journal of Health and Social Behaviour, 20(2), 100–108.

Kohli, M. (2007). The institutionalization of the life course: Looking back and ahead. Research in Human Development, 4(3-4), 253–271.

Levy, R., & Widmer, E. (2013). Gendered life courses between standardization and individualization. A European approach applied to Switzerland. LIT.

Macintyre, A. (1999). Dependent rational animals: Why human beings need the virtues. Open Court.

Marshall, V. W., & Mueller, M. M. (2003). Theoretical roots of the life-course perspective. In W. R. Heinz & V. W. Marshall (Eds.), Social dynamics of the life course (pp. 3–32). Walter de Gruyter, Inc.

Misztal, B. A. (2012). The challenges of vulnerability. Palgrave Macmillan.

Mortimer, J. T., & Shanahan, M. J. (Eds.). (2003). Handbook of the life course. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Press.

Overton, W. F. (2013). Relationalism and relational developmental systems: A paradigm for developmental science in the post-cartesian era. In R. M. Lerner & J. B. Benson (Eds.), Embodiement and epigenesis: Theoretical and Methodological issues in understanding the role of biology within the relational developmental system Part A: Philosophical, theoretical, and biological dimensions (pp. 21–64). Elsevier Inc. Academic Press.

Pearlin, L. I. (1989). The sociological study of stress. Journal of Health and Social Behaviour, 30(3), 241–256.

Pearlin, L. I., & Skaff, M. M. (1996). Stress and the life course. The Gerontologist, 36(2), 239–247.

Ranci, C. (2010). Social vulnerability in Europe. In C. Ranci (Ed.), Social vulnerability in Europe. The new configuration of social risks (pp. 3–24). Palgrave Macmillan.

Reese, H. W., & Smyer, M. A. (1983). The dimensionalization of life events. In E. J. Callahan & K. A. McCluskey (Eds.), Lifespan developmental psychology. Nonnormative life events (pp. 1–33). Academic.

Sapin, M., Spini, D., & Widmer, E. (2007). Les parcours de vie: de l’adolescence à la vie adulte. Presses Polytechniques et Universitaires Romandes.

Sapin, M., Widmer, E., & Igliesias, K. (2016). From support to overload: Patterns of positive and negative family relationships of adults with mental illness over time. Social Networks, 47, 59–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2016.04.002

Schröder-Butterfill, E., & Marianti, R. (2006). A framework for understanding old-age vulnerabilities. Ageing & Society, 26, 9–35.

Settersten, R. A., Jr. (2003). Invitation to the life course: The promise. In R. A. Settersten Jr. (Ed.), Invitation to the live course (pp. 1–12). Baywood Publishing Compani, Inc.

Settersten, R. A. Jr., Bernardi, L. Härkönen J., Antonucci, T. C. Dykstrae, P. A., Heckhausen, J., Kuh, D., Mayer, K. U. Moen, P., Mortimer, J. T., Mulderk, C. J., Smeeding, T. M., van der Lippe, T., Hagestad, G. O., Kohli, M., Levy, R., Schoon, I., & Thomson, B. (2020=). Understanding the effects of Covid-19 through a life course lens. Advances in Life Course Research. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcr.2020.100360. X. Merrien & J.-P. Tabin (Eds.), Regards croisés sur la pauvreté. Lausanne: Editions EESP.

Settersten, R. A. (2009). It takes two to Tango: The (Un)easy dance between life-course sociology and lifespan psychology. Advances in Life Course Research, 14(1–2), 74–81.

Spini, D. (2012). Vulnérabilités et trajectoires de vie: vers une alliance entre parcours de vie et politiques sociales. In J.-P. Tabin & F.-X. Merrien (Eds.), Regards Croisés sur la Pauvreté (pp. 61–70). Lausanne: Editions EESP.

Spini, D., Bernardi, L., & Oris, M. (2017). Towards a life course framework of vulnerability. Research in Human Development, 14(1), 5–25.

Spini, D., Jopp, D., Pin, S., & Stringhini, S. (2016). The multiplicity of ageing. Lessons for theory and conceptual development from longitudinal studies. In V. L. Bengston & R. A. Settersten Jr. (Eds.), Handbook of theories of ageing (pp. 669–690). Springer.

Tavaglione, N., Martin, A. K., Mezger, N., Durieux-Paillard, S., François, A., Jackson, Y., & Hurst, S. A. (2015). Fleshing out vulnerability. Bioethics, 29(2), 98–107. https://doi.org/10.1111/bioe.12065

Thoits, P. (2010). Stress and health: Major findings and policy implications. Journal of Health and Social Behaviour, 51(S), S41–S53.

Tobi, H., & Kampen, J. K. (2018). Research design: The methodology for interdisciplinary research framework. Quality & Quantity, 52(3), 1209–1225. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-017-0513-8

Turner, B. (2006). Vulnerability and human rights. Pennsylvania State University Press.

Vacchiano, M., & Spini, D. (2021). Networked lives. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour. https://doi.org/10.1111/jtsb.12265

Widmer, E., & Spini, D. (2017). Misleading norms and vulnerability in the life course: Definition and illustrations. Research in Human Development, 14(1), 52–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427609.2016.1268894

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Spini, D., Widmer, E. (2023). Introduction: Inhabiting Vulnerability Throughout the Life Course. In: Spini, D., Widmer, E. (eds) Withstanding Vulnerability throughout Adult Life. Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-4567-0_1

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-4567-0_1

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-19-4566-3

Online ISBN: 978-981-19-4567-0

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)