Abstract

Until the 1980s, Brazilian industrialization was oriented toward the domestic market. Although competitive pressure was weak, exporting companies and local subsidiaries of multinationals deployed the Japanese quality control model, which was considered the hallmark of the Japanese industry’s competitiveness. Individual companies and local business associations were the leading promoters of quality control, with the collaboration of JUSE. The first boom fell short of expectations because of the lack of understanding from corporate managers and some inter-cultural problems for workers in introducing Total Quality Control. The market liberalization since the 1990s set new ground for competitiveness-seeking quality control, supported by the government. The second boom did not materialize because of the industrial paradigm change for machine-based productivity gains, while Japanese style quality control is human-based. Still, we find that Japanese style quality control has been effectively used in non-industrial sectors such as public administration and healthcare. We argue that Japanese technical cooperation capitalizing on quality control methods will enhance Brazil’s labor productivity and social well-being.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The history of economic exchange between Japan and Brazil started with the Japanese migration in 1908.1 Full-fledged business relationships developed a half-century later during and after the high growth of the “Brazilian Miracle” from 1968 to 1973 under the state-led economic development model. The two countries strengthened economic cooperation and worked together to implement natural resource seeking national-projects2 which also motivated the boom of Japanese companies’ investment into Brazil.

However, in the 1980s, the Brazilian external debt crisis dealt a critical blow to the Brazil–Japan economic relationship. Japanese financial institutions suffered significant losses and a number of firms decided to withdraw investment from the Brazilian market which then entered a long slump. Since then, Japanese investment in Brazil has been stagnated or even in decline.

Japan amended the Immigration Act in 1990 in response to a labor shortage, granting special visa status with a working permit to the Brazilians of Japanese descent up to the third generation. This change triggered a massive migration of Brazilian workers to the Japanese labor market. However, the global financial crisis following the collapse of Lehman Brothers in 2008 caused massive layoffs. This was followed by a significant reverse migration.

The above paragraphs give an overview of 100 years of Japan–Brazil economic exchanges. A significant amount of literature exists on the topic. Examining Japanese immigration in Brazil, Saito ( 1960) pioneered empirical research based on his field survey in the 1950s on residential location choice and productive activities. Recently, Maruyama edited a commemorative publication (Maruyama 2010) of the 100th anniversary of immigration, which collects valuable studies by history and sociology experts on the nikkei community. Regarding economic cooperation, Japanese corporate investment, and external debt issues, Masao Kosaka, Yoichi Koike, and Toshiro Kobayashi respectively contributed detailed documents (Nihon-Brazil Kouryushi Henshu Iinkai 1995). Watanabe (1995) and Kajita et al. (2005) discussed the Brazilian migrant workers in Japan. This paper will examine Japan–Brazil economic exchange regarding the transfer of Japanese quality control methods to Brazil, a topic which has been very rarely discussed in previous studies.

“Cheap and poor in quality”: Japanese products were previously described this way in industrialized countries.3 To earn a good reputation, Japanese companies in the post-World War II period established unique quality control methods to eliminate the variation in quality. Their progress in this area enabled them to expand export market shares through mass production with stable product quality. Because of this, Japanese quality control methods attracted international attention as one of the pillars of support for the Japanese economy’s rapid growth in the post-war period. The US television network NBC aired an episode of the show NBC White Paper which was titled “If Japan Can…Why Can’t We?” and aired on June 24, 1980.4 It attributed Japanese firms’ secret of success to the faithful implementation of the statistical quality control proposed by an American statistician Dr. W. E. Deming. In 1989, MIT’s research report on American Industrial Competitiveness (Dertouzos et al. 1989) also examined the continuous improvement in Japan. The British Journal of Management Studies published a special issue in November 1995 (Vol. 32, Issue 6) on the transfer of Japanese management to alien institutional environments.

Japanese quality control is indeed based on ideas generated outside of Japan. These ideas include American scientific research ideas such as statistical quality control by Walter Andrew Shewhart, statistical process control methods by William Edwards Deming, total quality control discussed by Armand V. Feigenbaum, and quality control management as a management technique proposed by Joseph M. Juran. However, it was a group of Japanese scientists and engineers who gathered in the Union of Japanese Scientists and Engineers (JUSE) led by Dr. Kaoru Ishikawa (professor of engineering at the University of Tokyo) and crystalized the idea of Japanese quality control. They synthesized the new ideas5 and organized them as a practical system of Total Quality Control (TQC) consisting of Quality Control Circle (QCC) activity, PDCA (Plan-Do-Check-Action) Cycle, Quality Control 7 Tools, and Kaizen (continuous improvement).

These terms became buzz words in international business magazines in the 1980s and 1990s and learning from Japan had become a fashion. While companies in industrialized countries were eager to know what was threatening their competitiveness, businesspersons in developing countries showed keen interest in the Japanese model of rapid catch-up. The quality control method therefore became a prime reason for boosting Japan’s presence as a soft power nation.

Brazil was one of the most relevant countries in this regard. Industrialization progressed remarkably during the late 1970s to early 1980s. The first wave of Japanese management boom in Brazil gave it the necessary momentum to catch up to industrialized countries. Many experts from Japan were invited to give seminars to corporate managers. Quite a few companies in Brazil adopted QCC and TQC. Despite the significance of the exchanging knowledge about corporate management between Japan and Brazil, this topic has been almost ignored in previous studies on the history of the Japan–Brazil bilateral economic relationship. In this article, we document important events based on existing materials. This study will contribute to a better understanding that business values in both countries’, i.e., globalization of Japanese business and upgrading Brazilian product quality, did not interface well with each other, ending this phenomenon in a short boom.

In what follows, we will track the transfer of TQC to Brazil and draw lessons from those experiences. Section 7.2 covers stories from the early stages until the 1980s. Section 7.3 deals with the more recent period, beginning in the 1990s. We will see that episodes presented in the two sections have significantly different backgrounds. In the early stage, Brazilian industrial development was under a state-led developmental model in a closed domestic market. In recent years, significant market liberalization has been made, promoting global competition in cost and quality. The period covered in Sect. 7.3 has also seen considerable progress in automation and informatization of the production process, which affected the relevance of TQC. Section 7.4 reports two contemporary and relevant examples of TQC in non-industrial sectors in Brazil. Although TQC was initially born in the industrial sector, this technique is generally a helpful human power development tool for non-industrial sectors. We will portray the case of public sector administration and health care service. Section 7.5 will conclude the discussion.

2 Japanese TQC Transfer to Brazil Until the 1980s

According to previous studies in Brazil,6 QCC was first introduced in Brazil in 1971 by Volkswagen’s San Bernardo do Campo plant (State of São Paulo). According to the JUSE mission report to Latin America for quality control research in 1976 headed by Kaoru Ishikawa (Ishikawa and Hiromatsu 1977), the introduction of QCC was a local initiative and not a transfer from Germany. Instead, Volkswagen diffused the know-how on QCC from Brazil back to Germany. According to the same report, Usiminas Steel (the Japan–Brazil joint venture whose Japanese shareholders were Yahata Steel and Fuji Steel—merged as Nippon Steel in 1970 and NKK—now JFE Steel) initiated QCC in 1970. Usiminas had already implemented a joint activity of QCC with Volkswagen and Ishibras (Ishikawajima Harima Heavy Industry (IHI)’s shipyard in Rio de Janeiro). Therefore, it might be true that Volkswagen learned Japanese style QCC from Usiminas or Ishibras. After the 1973 visit to Brazil, Kusaba (1974) reported that he witnessed Volkswagen already actively engaged in Japanese-style quality control, and Johnson & Johnson also started QCC in September 1972.

Following these pioneering companies, QCC in Brazil saw the first boom from the late 1970s to the early 1980s. Yuki (1988) reports that there were about 3000 companies implementing QCC in 1979. Ferro and Grande (1997) explained the background of the QCC boom: (1) it was worth imitating Japan’s successful experience; (2) QCC seemed costless without investment and organizational change; and (3) there was a positive image of introducing the participatory decision making of QCC in the workplace in the period of political transition from the military authoritarianism to democracy. In other words, QCC was conceived as a managerial method that could bring a good image to the company ((1) and (3)) and enabled productivity gains without further costs (2).

It must be emphasized that the Japanese-style QCC required that workers’ participation adapted to the Brazilian labor environment where management exerted strong power over workers. Humphrey (1993) argued that having managers consider workers’ proposals through QCC was useful in understanding workers’ demand before colliding with the labor union, thus lowering the turnover rate and helping them retain the skilled labor force.7 Kubo and Farina (2013) mentioned that the attitude of Brazilian managers toward QCC was authoritarian.8 They found that managers did not fully respect workers’ independence to make suggestions for improvement and did not encourage them to participate spontaneously. According to Fleury (1995), Brazilian companies’ managers failed to understand that without harnessing corporate strategy changes, the productivity improvements that occurred because of QCC activities’ achievements quickly faded.

Because a firm is an organic organization consisting of interrelated sections, changes in one part may require adjustments in other parts. Thus, total company-wide initiative is necessary to adapt workers’ suggestions for improvement arising from each section, sometimes requiring corporate structure reforms. In Japanese-style quality control, QCC is not a means to the end; it is a part of total quality control (TQC) to detect problems and maintain the company-wide continuous improvement through the PDCA (Plan-Do-Check-Action) cycle.

QCC essentially depends on workers’ voluntary participation. Each shop floor-level QCC has the role of detecting waste and dysfunctions and proposing improvements. However, if the employees were not informed of the company-wide goal and the way in which these improvements could contribute to their company’s growth, they may feel suspicious and believe that the management would exploit frontline workers’ knowledge to reduce the labor force. Without employees’ trust, the QCC imposed from above would not work well. Workers demand recognition from managers and they need to be motivated by seeing their suggestions influence company strategy and contribute to the company’s growth.

The volunteerism is also cultivated by enhanced pleasure at work. According to Kusaba (1984), foreigners tend to appreciate Japanese quality control only on its scientific aspects of using statistical methods, but they overlook the human elements of QCC, considering that the group working on QCC only has the emotional value of a sense of unity. In this regard, Kusaba (1984) emphasizes that workers feel progress in their personal capability from learning the logical thinking and the pleasure of working in a good social relationship obtained from cooperating in solving problems at work. He remarked on the necessity of disseminating an accurate idea of TQC as the “company-wide” movement and its advantage from the combination of scientific and human sides.

Observing the situation in the early stage of the quality management in Brazil, Ishikawa and Hiromatsu (1977) noted that “Brazilian companies consider that QCC is sufficient for quality management,” implying the lack of total company-wide initiatives. They further observed that “companies consider quality to be controlled by an inspection at the end of the production line.” This attitude differs from the objective of Japanese-style quality control which uses stringent control to eliminate defects and unevenness that exists in the production process. They concluded “Brazilian companies still need to figure out what is quality control.” Nishimura (1984) pointed out that Brazilian managers initially had incorrect ideas that QCC would result in quick outcomes in corporate profit. Ferro and Grande (1997) described how Brazilian companies understood that the work floor level quality controls were disconnected from company management.

These views reflect difficulties in transplanting the Japanese-style quality control to the Brazilian environment. Previous studies pointed out that the hostile manager-worker relationship adversely affected the introduction of company-wide quality control, making the QCC boom in the early 1980s short-lived. The participatory decision making reached a deadlock that faced attacks from both trade union’s obstructions and dissatisfactions the middle-managers who feared infringement on their authority to make decisions. As Brazil faced a severe macroeconomic crisis in the second half of the 1980s, the labor market condition deteriorated with a massive job cut. The labor relations became even more confrontational, compelling QCC to decline (Humphrey 1993).

It is known that workers at that time had a negative view of QCC participation. From the study on labor relations in the São Paulo State ABC Region (consisting of Santo André, São Bernardo do Campo, and São Caetano, adjacent to São Paulo City), Carvalho (1987) found that, combined with the electronically controlled automation system promoted in that period, QCC was seen as a labor-saving productivity enhancement tool, meaning an enemy for workers. The pioneering QCC in Volkswagen failed in early 1980. When the company tried to reinvent QCC in 1982, workers harshly boycotted it (Hirata 1983).

Some authors attributed the TQC success in Japan to the Japanese socio-cultural uniqueness. For example, Hirata (1983) found that the development of QCC in Japan is due to specific social conditions, such as the family perception that allows for a work-centered life, the sense of belonging to the company that is formed under the lifetime employment and seniority system, the small wage gap among employees which promotes cooperation, a principle for consensus decision making, and strong collectivism that is intolerant to deviation. She found it difficult to disseminate QCC in Brazil because the social conditions vary.

Japanese parties involved in TQC also expressed skepticism about the transferability of Japanese TQC to foreign companies (Ishikawa Kaoru Sensei Tsuisouroku Henshuu Iinkai 1993). JUSE launched an international diffusion of Japanese-style TQC in the 1960s. The international activities initially had a publicity purpose for export promotion to show that the high quality of Japanese products is sustained by QCC without giving practical details. In the pioneering comprehensive textbook of Japanese TQC in English,9 one of JUSE’s leading scientists Kaoru Ishikawa considered that Japanese society’s peculiarities worked as a pre-condition for the success of Japanese quality control and did not hide a believe that it would be difficult to perform Japanese quality management in different cultures in foreign countries (Ishikawa 1985, pp. 23–36).

Afterwards, as Japanese companies increased overseas production, the purpose of JUSE’s international activities shifted to support for overseas production of Japanese companies to increase competitiveness. The chief recipients of dissemination were still limited to Japanese affiliates. One way of thinking at that time was that “a foreigner can see the benefit of Japanese-style TQC only after he experienced by himself receiving a hands-on training of Japanese instructors” (Kusaba 1984).

Japanese businesspeople and researchers often emphasize the role of TQC in Japan’s remarkable recovery from the devastating destruction of World War II. However, the thought that “only Japanese can understand” and abandoning further logical explanation hampered international diffusion and understanding of the Japanese-style TQC concept remained obscure overseas. These shortcomings caused dubious perceptions or even misinterpretations. One illustration was the “Japan-bashing” in the late 1980s from the Western world, putting forward the idea that Japanese products’ high competitiveness was inexplicable unless Japanese companies conducted unfair competition based on different rules. Harada (1984) argued that the spirit of the service to mankind alone does not go very far and the Japanese government must support disseminating and popularizing the precise know-how of TQC in foreign countries. Understandably, a private institution like JUSE alone could not afford to develop such activities. The government should have taken these recommendations more seriously and taken steps to make Japanese-style TQC known on an international level. For example, the knowledge transfer could have been facilitated by translating practical manuals to foreign languages and the development of teaching materials adapted to the specific context of other cultures.

Japanese companies in Brazil, like in other Japanese overseas affiliates, tended to stop using TQC because they realized that the participatory, bottom-up, and company-wide approach was not possible in their environment. The local affiliates lacked the knowledge to adapt the Japanese-style TQC to local conditions. Because of this, Japanese affiliates in Brazil could not become leaders in diffusing TQC accurately to surrounding companies. To our knowledge, Rohm Indústria Eletrônica Ltda (Rohm I. E. L. at Mogi das Cruzes, State of São Paulo) was an exception. The Brazilian affiliate of Rohm introduced QCC in 1974. It promoted awareness of QCC by establishing the Association of Quality Control in the Paraiba Valley (AVCQ10 in the Portuguese acronym) with companies in the region such as Johnson & Jonson (Hiraki 1975). Further details of the case of Rohm I. E. L. are provided in Column 7.1.

Column 7.1 QCC in Rohm Indústria Eletrônica Ltda (Rohm I. E. L.)

Rohm I. E. L. was a subsidiary of Rohm Co., Ltd., headquartered in Kyoto, established in November 1972 in Mogi das Cruzes, São Paulo State. The plant produced electronic components such as resistors mainly for export to the US market. Production started on August 9, 1973 and continued until June 1997.

Before starting production, the company sent 12 senior production managers to the Rohm headquarters as technical trainees from January to May to learn both production technology and QCC. After returning to Brazil, these trainees became instructors and educated middle managers about QCC to make trained leaders. Production trainers were not Japanese employees.

QCC activities in the company started in July 1973 with eight circle groups, then expanded quickly. In October, the company held the first QCC workshop with 15 groups. The company had the workshop in July 1974, with 31 groups inviting Johnson & Johnson and other neighborhood companies. It became a founding member of the Association of Quality Control in Paraiba Valley (AVCQ).

The human element is critical in improving productivity and reducing defect rates immediately after plant start-up. On-the-job training, including QCC, was very active and showed significant results. However, the number of workers rapidly increased as exports expanded, and QCC became less useful for productivity improvement because the newly added workers did not share the knowledge. Hit by the export disruption during the recession after the first oil shock in 1973, the company had to reduce employment substantially through layoffs. QCC in Rohm I. E. L. stopped for almost one year after May 1975.

As the economies of developed countries recovered, production resumed quickly. However, the sudden increase in employment while employees’ awareness of quality remained low partly due to the stagnation of QCC activities caused the defect rate to increase. In May, the company increased automation by investing in state-of-the-art equipment to minimize human errors. At the same time, it resumed QCC activities introducing the remuneration system for excellent suggestions from workers. The combination of top-down and bottom-up approaches led to a dramatic increase in productivity and decreased defective rate. In 1983, the company established the TQC headquarters with the president at the top of the structure to coordinate the company-wide quality control activities.

According to Fujiyoshi Hirata, the original Japanese-style bottom-up approach in quality control based on continuous QCC does not apply to Brazil because the education level, racial and cultural diversity, and labor relations are different from Japan. However, only the top-down labor management would not be able to unleash employees’ human potential. Referring to the concept of the five levels of Maslow’s “hierarchy of needs,” Hirata points out that managers should not ignore the human aspect of work in which people desire to realize their needs. In a society where people are diverse and developing like Brazil, what employees want to accomplish will change according to the company’s growth stages and the society’s developmental phase. Therefore, management can achieve the best performance in quality by presenting the optimal combination of top-down and bottom-up approaches adapting to the changing circumstances. Through the experience in Rohm I. E. L., Hirata emphasizes the importance of interact with employees and choose the optimal combination at each stage.

This column is based on the online interview with Mr. Fujiyoshi Hirata on May 7, 2020.

Although the first wave of Japanese-style TQC in Brazil ended after the temporary boom, QCC put down roots in Brazilian companies to some degree. Ferro and Grande (1997) identified some interesting adaptations for localization. First, the QCC came to be known by a wide variety of different names such as “quality circle,” “creative circle for improvement,” or “dynamic quality circle” because people felt top-down administrative nuance from the term “control.” Second, factory floor level circles became organized under the company-wide committee or coordinator, thus positioning them in formal company organization. This aspect implies that the company-wide total quality control concept gained recognition and higher-class managers have become more involved. Third, Ferro and Grande found that QCC in Brazil is composed by employees from different sections and mixed job ranks, including supervisory positions, significantly transformed from the original Japanese style QCC composed by workers in the same team and from the same job classification. Fourth, it became more likely that managers give directions to QCC’s theme choice, rather than leaving it free to circles. Activities of QCC have more links to companies’ actions in quality improvement. Fifth, many companies introduced a monetary reward system reflecting the results of QCC to provide incentives for participation.

Considering the situation in this way, when voluntary participation of shop floor workers and company-wide total involvement are the two pillars of successful implementation of QCC, the adaptation to Brazil required more emphasis on the latter, at the sacrifice of the former to some degree. In the original Japanese model, workers volunteerism and the company wide total involvement went hand-in-hand. Because the post-war period’s Japanese labor relation was based on the life-time employment system, workers could consider a long-term optimization, under which continued company growth would increase employees’ income and expand future promotion opportunities. In Brazilian labor relations, where managers and workers belong to different classes, workers may be excluded from the profits raised by higher labor productivity. Under a semi-contractual agreement, where managers suggest quality circle themes and workers receive a monetary reward for good suggestions, quality circles may work better than expecting workers to volunteer participation. As Hosono (2009) pointed out, the adaptation of the Japanese-made approach to the local context is essential. We can conclude that the transformation of QCC that is shown by Ferro and Grande (1997) incorporated the Brazilian way of promoting engagement of both workers and managers.

3 Japanese-Style TQC in Brazil Since the 1990s

The economic liberalization during the late 1980s and the early 1990s brought about a shift in the competition paradigm in Brazilian industry and its perception on quality as a core strategy (Miyake 1996). The government took an initiative to support this transition, turning the focus of industrial policies from import substitution industrialization for the protected market to the enhancement of competitiveness with higher quality, innovation, and productivity.

Under such circumstances, attention to quality management gained momentum. The Science and Technology Development Support Program (Programa de Apoio ao Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico, PADCT) began in 1984, and the Bureau of Industrial Technology launched the Quality Control Specialist Development Project (Projeto de Especialização em Gestão da Qualidade, PEGQ) in 1988. The establishment of the Brazilian quality assurance system based on the international standardization ISO 9000 in 1990 was part of the project. In September 1990, the Consumer Protection Act (Código de Defesa do Consumidor) was enacted to regulate manufacturers’ product liability.

Also in 1990, the government launched a new industrial policy called the National Plan for Quality and Productivity (Programa Brasileiro da Qualidade e Produtividade, PBQP). As part of PBQP, the National Quality Award (Prêmio Nacional da Qualidade) was established in 1992 and was modeled after the United States Malcolm Baldridge Award.11 In accord with PBQP, private institutions such as CNI (National Industrial Federation), government-sponsored “S-system,” including SENAI (industrial technology), SESC (commercial), SEBRAE (small enterprise support), and the local industrial and commercial chambers offered training courses on statistical techniques and quality management. Companies were able to utilize these services along with the training in-house (Fernandes 2011).

The quality movement provoked the second wave of Japanese-style TQC boom in Brazil. PEGQ designated Minas Gerais Federal University (UFMG) and the University of São Paulo (USP) as the core institutions for the capacity development of quality control specialist training with support from JUSE. The Christiano Ottoni Foundation (FCO) of the Faculty of Engineering of UFMG signed an agreement with JUSE. It started with two professors of the FCO, José Martins de Godoy and Vicente Falconi Campos commissioned by the government to study projects that had increased product quality and productivity of companies since the mid-1980s. They received the advice of W.E. Deming and attended JUSE seminars. Under the agreement, the FCO sent 33 technical groups including 1100 businesspeople to Japan to attend workshops (Godoy 2015). JUSE also sent lecturers to workshops in major cities in Brazil. Because of this, progressively more FCO specialists were trained by JUSE and could provide consulting services on 5S and QCC to Brazilian companies. FCO collaborated with JUSE to publish textbooks on TQC in Portuguese.

The Carlos Vanzolini Foundation (FCAV)12 of the Engineering School (Poli) at USP established the education program on quality control in 1995 with the assistance of the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO). JUSE also supported this program by providing technical seminars to FCAV’s instructors in Japan and dispatching an on-site supervisor to USP.

As part of the PBQP, the Brazilian government requested technical cooperation from Japan to establish the Brazilian Institute of Quality and Productivity (Instituto Brasileiro de Qualidade e Produtividade, IBQP-PR), located in Curitiba in Paraná State. The Japan International Cooperation Agency aided the project from 1995 to 2000 with the technical support of the Japan Productivity Center (JPC). During this period, 12 long-term experts and 19 short-term experts were dispatched from Japan. On the Brazilian side, 17 trainees were invited to Japan for capacity development. During the project period, 82 seminars and 26 training courses on quality and productivity were organized with the participation of IBQP-PR. Factory floor level consultation activities were carried out by Japanese and Brazilian experts for more than 20 enterprises (Hosono 2009). Following the establishment of IBQP-PR and the staff capacitation, JICA extended the South–South and triangular cooperation modality fund in 2001–2005 to support IBQP-PR’s implementation of the training program for professionals from other Latin American countries and Portuguese-speaking African countries to receive training on quality control from Brazilian instructors. While IBQP-PR is a private non-profit organization, the government granted IBQP a civil organization status for the public interest in 2002, which enabled it to sign partnership agreements with public institutions and develop jointly specific projects.

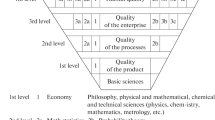

IBQP-PR proposed the concept of “systemic productivity (produtividade sistêmica).” Hosono (2009, p. 31) explains that systemic productivity defines productivity as a social function because the constant improvement of productivity in each organization must help to create the conditions of sustainable development and better quality of life. In order to assist with decision making in continuous improvement at each organization level under a highly complex Brazilian situation of interwoven intra- and inter-organizational factors affecting productivity, IBQP-PR adopted the Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP), a quantitative method designed by the Institute for Manufacturing of University of Cambridge (King et al. 2014).

Compared to the private sector centered transfer of Japanese-style TQC until 1980s, the second wave included relevant engagement of public institutions in both Japanese diffusers and Brazilian receptors. Although the systemic support stimulated exchanges, these initiatives had already missed an opportunity to upscale the cooperation in quality control because of a change in the perception of quality assurance.

During the globalization in the 1990s, the quality assurance based on the ISO 9000s accreditation system arose as a new concept of quality management in Europe and quickly gained popularity worldwide. TQC and ISO 9000s have different foci. While TQC aims at improving continuously every facet of an organization through management commitment and employee training and education so that customer requirements are met precisely, ISO 9000s accreditation assures that company’s practices are in conformance with its stated quality systems. The implementation of TQC represents the company’s policy of considering customer needs and satisfaction as a part of its strategy to gain competitive advantage. The ISO 9000s accreditation signifies the company’s consistency in compliance with their stated production method to provide products or services in the quality they have committed to (Zhu 1999). While ISO 9000s accreditation is warranted by an internationally acknowledged certificate, it is hard to prove the successfulness of TQC outside of country specific TQC awards. Because of this, TQC and ISO 9000s are not mutually exclusive (Zhu 1999), but companies competing in the international market pay more attention to TQC as a system of quality assurance.

A recent study by Siltori et al. (2020) found that Brazilian companies expected that ISO 9000s accreditation could increase sales by assuring high quality, consumer satisfaction, and cost justification. However, they recognized that it would not enhance employees’ awareness of quality and would not motivate quality improvement. ISO only gives external validation of its established product quality, but it does not show its ability to improve quality. Bernardino et al. (2016) observe that Brazilian companies often refer to the conceptual legacy of TQC to motivate quality improvements, such as a statistical control of the production process and PDCA. Nevertheless, they have already abandoned essential TQC methods, such as QCC seven tools of Ishikawa (1985).

Obtaining the ISO 9000s certificate requires companies to document in great detail the entire quality assurance system process. They also need to provide evidence that workers strictly follow the manuals and reassure customers that information can always be accessed. Once adopted, this system does not allow a company to change the production process and the line layout that had been agreed with customers, leaving no room for the TQC-style continuous improvement with suggestions from workers. These processes need strong leadership from the high-level management. According to Kubo and Farina (2013), the Brazilian production site is deeply rooted in the top-down style Taylorism13 where elements required for a successful TQC, such as authority delegated to operators, volunteerism, and teamwork are weak. Brazilian companies’ culture is therefore more compatible to quality management guided by ISO 9000s.

In addition to the popularity of alternative quality management, Japanese-style TQC was overshadowed by the recent technological developments, where automation technology has substantially reduced human factors in making a product. In the terms of the business community, the “5Ms” represent the man (labor), the materials, the methods (of production), the machinery, and the measurement (and inspection) and are considered the core of quality management. TQC propels continuous improvement in labor and production methods. Brazilian companies often emphasize the acquisition of the latest machinery and materials, incorporating cutting-edge technology that results from overseas research and development to realize leap-frog progress in quality and productivity. This strategy prevails over continuous improvement and accumulation of internal knowledge embodied in labor and methods. In particular, with the introduction of modern equipment incorporating advanced automation and electronic control, high quality is to be preset by the product design and stringently standardized by reducing the interference of human factors, which are prone to errors, to a minimum.

In fact, the QCC activities were already in decline in Japan as well in the 1990s.14 Dahlgaard-Park (2011) argues that Japanese companies compete more by cost than quality in the long-term recession after the bubble economy burst, causing a decline in quality control. As in Brazil, Japanese manufacturing builds in quality during the product design process, and the workers’ contribution to quality improvement has become less relevant. With the decay of the expectation of a life-time employment and increase in temporary and non-permanent (including foreign) workers, volunteerism to participate in QCC after business hours has reduced, and employees’ resistance to being required to participate in unpaid QCC has increased. Such structural change diminished the significance of QCC as human resource development.

4 Contemporary Cases of TQC in Brazil

So far, we have discussed pathways for the diffusion of Japanese-style TQC in Brazil. We observed that TQC was originally modeled for continuous improvement at the production level of manufacturing industries, and also contributed to employees’ empowerment. But many have considered the trend of globalization and automation have greatly diminished the relevance of QCC as a quality management tool in manufacturing.

Nonetheless, TQC still makes strong sense in labor intensive activities, such as services, even in the contemporary scene. In this section, we will demonstrate that Brazil is not an exception. We will shed light on two cases: public administration from the case of the São Paulo State government and health care service and from the case of Santa Cruz Japanese Hospital in Vila Mariana district of São Paulo City.

4.1 Public E-Procurement Through Bolsa Eletrônica de Compras (BEC), São Paulo State Government

The Brazilian public sector has initiatives to induce quality in its services. According to Brazil’s former Ministry of Federal Administration (Brasil 1997, pp. 12, 14–15), one of the cornerstones to modernize the public sector is implementing a quality program to improve its efficiency and offer better services to citizens. The quality would be shown by performance indicators and third-party certification as a seal of approval. The Ministry of Federal Administration (Brasil 1997, pp. 29–55) provides a step-by-step process to implement quality programs in different public sector secretaries, departments, and agencies and recommends the PDCA cycle as a tool for continuous management improvement.

Concerning Bresser-Pereira (2002), in the late 1990s, the implementation of total quality management “in public administration gained legitimacy and became the official management strategy to implement the [public administrative] reform.” In Brazil, national and sub-national public entities have used total quality management to change and improve the public sector.

Quality management continues to be a concern in the Brazilian public sector. Brazil’s federal government (Brasil 2018) conducted a survey to the national public entities regarding their process of quality evaluation. Using a federal government-sponsored study, Pedrosa and Menezes (2019) proposed a model to evaluate the management quality in services provided by national public entities to the citizens.

Pereira (2012, pp. 108–109) analyses the relationship between ISO 9001 certification and management models: hoshin kanri relates to some of ISO 9001 requirements, while Total Quality Management relates to all ISO 9001 requirements, meaning the Quality Management System. These are examples of quality management models that have been introduced, transferred to Brazil from Japan, and have been used both by the private and public sector.

One case where a quality management system has been implemented in sub-national government is the Bolsa Eletrônica de Compras (BEC), or the public e-procurement system, at the São Paulo State’s Secretary of Finance.15 BEC is a procurement system where public entities buy goods and services and firms sell them by reverse auction (São Paulo, Secretaria da Fazenda e Planejamento, n.d.). Establishing the Quality Management System at BEC started in 2009 and got an ISO 9001 certificate in 2010 (Pereira 2012, pp. 73, 114; Pereira et al. 2010, p. 3).

As an example of the quality benchmarks in the public sector, we detail the BEC case. In the early 2000s, the São Paulo State’s Secretary of Finance had a series of projects to modernize structures, processes, infrastructure, internet networks, and the use of information of technology. These projects had viability funded by the Interamerican Bank of Development (Brasil 2003, pp. 1, 45). A modern internet-based government procurement system was built with information technology, and the BEC was established in 2000.

Using BEC the State of São Paulo government had saved up to 20% from the reference price in the early years of operation (Brasil 2003, p. 45). Among the products or services that could be purchased through the internet, about 21% had already bought by BEC in 2003, and the remaining value was purchased through traditional methods (Izaac Filho 2004, p. 57).

The most recent data shows that BEC reverse auction has saved an average of 27% every year since 2000, if allocated budgeted value is compared with the negotiated amount and more than 5 million products and services have already been purchased.

In the beginning, BEC was deployed for just one of the government procurement modalities called convite. Negotiations expanded to medical drugs procurement in 2002, then extended to the São Paulo state cities, universities, and public enterprises in 2003. The State of São Paulo government issued a decree obliging the entire direct administration to buy using BEC in 2007 (Pereira 2012, p. 60). Hence, the negotiations through BEC had begun with a limited scope, then gradually expanded. Finally, all the State of São Paulo public entities have negotiated using this system of reverse auction.

In the BEC, the auctioneers must be public servants who have received training provided by the São Paulo State Government School. Before and after the auction, other public servants prepare tasks that involve paperwork. When the auctions happen, the auctioneer interacts with the suppliers. The auctioneer is anonymous until the auction finishes.

During all processes, there are human interactions, like paperwork preparation, the auction, and writing reports. When people operate the process, continuous quality control would be pivotal to keeping the system trustworthy.

The process to establish the Quality Management System to the BEC started in 2009, when the São Paulo State Secretary of Government selected BEC as the benchmark of quality in the public sector. BEC top officials have decided to implement the ISO 9001, a process-based quality management system. A consulting firm has contracted to revise the processes by a fund from the Interamerican Bank of Development.

Concerning Pereira (2012), ISO 9001 certification to BEC would be a way to get trust from the firms. The certification would attract better suppliers with a fair price; hence, it would show the citizens the optimal use of public resources.

The consulting firm has recommended some changes to BEC to acquire the ISO 9001, which it has received since 2010 (Pereira 2012, p. 114; Pereira et al. 2010, p. 3). The last certification was acquired in 2019, and it expires in September 2022.

In 2011, the São Paulo State government had 85 public entities, among them 25 secretaries that compose the direct administration, 20 public enterprises, 24 public authorities, and 16 foundations. There was an ombudsman or a consumer service in all of them, except in one, and almost one-third of them had a Quality Management System in some department inside the entity. Among the secretaries, just 3 had Quality Management Systems in some departments (Pereira et al. 2010, pp. 65–72).

If the citizen has some complaint and calls the ombudsman, the service offered by the public entity could improve in quality, which would be a reactive action. However, if a department has a formal Quality Management System, this would be a proactive action from the public sector. BEC is an example of a case related to proactive action.

A team to follow and support the quality of the procurement process inside the BEC was first established and operated in 2009 when the Quality Management System began. The Department of Quality and Research was formally established in 2014, after Pereira (2012) analyzed the governance of similar departments at public enterprises and public authorities.

BEC’s Quality Management System has 13 processes, eight which relate to BEC users, four for support, and one management process. They all have aims, indexes, and instructions on how to measure them (Pereira 2012, pp. 79, 80, 83, 86, 92), which gives them objective measures for quality management.

Besides the Department of Quality and Research, there is a Committee of Quality. Their members are BEC’s process managers, teams’ leaders, and top officials to support and provide feedback to the BEC’s Management Quality System. This Committee has a meeting every month, and the Committee has a meeting with top management every semester. This last meeting overlapped the period when an external audit occurs to recertify the ISO 9001. Improvement of BEC’s process has emerged after completing the external audit and meeting with top management. The concept of maintaining quality has been part of strategic planning at BEC since 2010 and maintaining the ISO certification has motivated BEC officials and public servants to follow, review, and improve the processes.

There are around 1000 procuring units allowed to buy through BEC, and regular surveys on satisfaction have been sent to them to measure the service’s quality. Also, internal feedback surveys have been completed with the officials and public servants related to BEC. Hence, these surveys are also a vital tool for quality maintenance.

4.2 Toyota Production System in Santa Cruz Hospital

Next, we turn to the case of quality control applications in healthcare organizations. Reliability of healthcare depends on the systemic capability of each organization to comply with its expected function under pre-determined conditions with reasonable cost-efficiency. The confidence in the healthcare system, in turn, rests on the reliability of each organization. To ensure trust, the government must provide institutional support with appropriate regulation, safety standardization protocols, and funding, etc.

Collins et al. (2015) point out that healthcare organizations face increasingly complex situations consisting of (1) changing healthcare demand due to the aging population; (2) more intense competition among hospitals; (3) challenges of improving patients’ safety using advanced technology; (4) eroding profits with rising costs; (5) labor shortage; and (6) necessity of adopting higher quality and safety standards to achieve higher rewards. Quality control in healthcare service is essential for strengthening organizational capacity to consolidate the reliability of each healthcare organization under such conditions. It aims to create routines for procedures through continuous improvement to accomplish higher standards and safety with smaller dispersion in healthcare under highly diverse conditions.

Fillingham (2007) claims that in hospitals, staff usually work in departmental silos. The result is a process that is riddled with errors, duplication, and delay, which frustrates frontline staff and leaves them dispirited. Commonly, waste occurs in transport (movement of patients and equipment); inventory (unneeded stocks and supplies); motion (movement of staff and information); waiting (delays in diagnosis and treatment); over-production (unnecessary tests); over-burden (stressed, overworked staff); and defects (medication errors, infections). Removing as many frustrations as possible can make work a more fulfilling experience.

Beginning in the 2000s, Virginia Mason Medical Center in Seattle, WA, launched the implementation of the Toyota Production System (TPS) for the management of the hospital. Virginia Mason’s leaders adopted the TPS method of manufacturing learned from a Japanese consulting company and established the “Virginia Mason Production System,” also known as the “Lean Hospital.” The successful records in healthcare outcomes and financial improvements attracted attention, including from Japan.

Because of successful cases in North America, the lean model for healthcare is known of in Brazil but is rarely used in practice; it was pioneered by Hospital Japonês Santa Cruz (HJSC). HJSP was founded in 1939 in São Paulo city with the original mission of supporting the community of Japanese immigrants who had difficulty communicating with Brazilian healthcare organizations. The hospital was founded through donations, including one from the Imperial family of Japan. As of June 2020, it consists of 40 departments and three outpatient clinics, ambulatory, and two surgical centers. There are 170 inpatients beds. It acts as a referral institution in many areas, including ophthalmology, neurology, orthopedic, and cardiology (Hospital Japonês Santa Cruz 2021).

It can be said that this endeavor is unique because it is based on the cooperation between HJSC and Toyota itself. At the 2014 Japan Festival in São Paulo, Toyota Latin America and the Caribbean CEO Mr. Steve St. Angelo informally sought out Mr. Renato Ishikawa, then CEO of HJSC, to learn about his interest in implementing the TPS at the HJSC. According to Mr. Ishikawa, Toyota wanted to contribute to the Japanese-Brazilian community, as it boosts credibility in the Brazilian market for the products with a Japanese brand.

The Toyota group visited the HJSC for initial situation mapping. They found it appropriate to start with the emergency care section because the large volume of entangled back-and-forth flow of more than 2000 patients a month left sufficient room for improvement. Given the similarity to production line optimization, Toyota engineers were able to help remove waste in the process. However, it was a learning experience to implement TPS in a non-manufacturing sector.

Compared to the figures at the start of TPS adoption (in 2015), this project has achieved several positive results by 2020. There were no deaths in emergency care in that year. Moreover, the patient’s average stay has been reduced from 240–160 min, with the waiting time reduced from 68 to 30 min (HJSC 2021). By reorganizing medicine and materials stock bins, the time needed for staff to replenish instruments/medicine trays has been reduced from 46 to 36 s. Also, the time spent providing a patient with prescribed medicines declined from 383 to 361 seconds.16

Costa et al. (2017) delineated four obstacles when Brazilian healthcare organizations introduce the “lean” concept. The first is human factors originating from employees’ distrust, physicians’ disinterest, conflicts of interest, and frustrations with previous attempts in organizational changes. The second is the difficulty in extending the lean practices to the outsourced contractors. The third is the necessity for technical support from expert consultants because the lean hospital knowledge is not widespread. The fourth is the relationship between top level hospital management and medical staff to ensure continuity of continuous improvement.

Concerning the obstacles from human factors, Fillingham (2007) reports from experiences at Bolton Hospital (UK) that many of the lean exercises were counter-cultural for the healthcare service workers in the UK. Many initially said that “we are not Japanese and we do not make cars!” when the process was explained to them, which Fillingham identified as inevitable. Many also thought that they had would need to work more to achieve higher quality. However, they learned that sound quality could be achieved with less effort from workers. In the case of HJSC, managers understood that the hospital staff accepted TPS as a work philosophy, not just as a management method for cost reduction. Employees recognized TPS as a factor that helped them avoid rework which reduced their frustration at work.

Concerning the external support, the collaboration with Toyota was essential for HJSC. In the beginning, Toyota provided training to implement TPS at HJSC. Later, the implementation was handed over to HJSC. To ensure continuity, HJSC established a training program to integrate new employees into the TPS. During the training program, the quality supervisor gives a 1.5-h lecture on the concepts of quality and TPS. Currently, HJSC maintains contact with the Toyota TPS crew and receives their occasional visit for technical observances. Having the external input from Toyota is necessary to verify how the implementation is being carried out. With their help, the implementation of TPS in HJSC has expanded to other types of flow amount control such as the surgery centers’ patients monitoring, inpatient admission, medication monitoring, nutrition and diet regime, outpatients’ appointments, and medical examination process control. There are also visits from other hospitals, such as Hospital do Coração, to HJSC to learn about the TPS.

Other fundamental factors supporting continuity are the inheritance of Japanese culture in HJSC, the strong leadership of Mr. Renato Ishikawa, and the staff’s working experiences in Japan through exchange agreements with Osaka University, Tsukuba University, and Kyushu University.

We should note that the adoption of TQC in health care management constitutes a key strategy in JICA’s technical assistance in South Asia and Africa. For more information about this, please see Column 7.2. This approach can be extended to Brazil and other Latin American countries.

Column 7.2 JICA’s Health Sector Cooperation with the Quality Control Method

While healthcare demand and complexity increase, healthcare providers face resource scarcity in staff, materials and equipment, and time. Healthcare workers often blame underinvestment for low efficiency. In trying to deliver higher quality services under such constraints, healthcare institutions in Japan often practice the total quality management method based on the 5S-Kaizen-TQM. The 5S stands for the five Japanese words “Seiri, Seiton, Seiso, Seiketsu, and Shitsuke,” which can be translated in English as “Sort, Set in order, Shine, Standardize, and Sustain” (Kanamori et al. 2016). The 5S establishes the discipline to create a clean and well-organized workplace. It contributes to reducing the time wasted in searching for objects and reduces the expenses caused by procuring unnecessary materials. It is also intended to enhance healthcare workers’ well-being and safety. Kanamori et al. (2016) found that 5S is a foundation or starting point for improving safety, efficiency, or patient-centeredness in healthcare, even among resource-constrained facilities.

Kaizen and TQM refer to the integral problem detection and continuous improvement process, deploying the quality control circle (QCC) activities and the organization-led plan-do-check-action (PDCA) cycle. The 5S-Kaizen-TQM brings together the frontline healthcare workers’ experiences, successes and failures, continuous quality improvement, and communication across the vertical management hierarchy and the inter-sectional divisions. It helps prevent human errors by keeping everyone informed of rules and empowering healthcare workers to enact changes.

The 5S in developing countries began at Castle Street Hospital in Sri Lanka in 2000. It was then upscaled to the National Health Master Plan, which was supported by the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) (Hasegawa and Karandagoda 2013). Building on its success, JICA designed the Better Hospital Service Program in 2007 to transfer the 5S-Kaizen-TQM method in Africa’s health sector as a triangular cooperation of Japan, Sri Lanka, and fifteen African countries. This allowed the African countries to learn from Sri Lanka’s best practices with Japanese health experts’ aid. The program was divided into two phases. The first phase was to understand the concept of 5S and adapt it to each country’s local context through experimentations. After human resource formation was complete, the second phase was to learn the Kaizen process and the total quality management methods under the pilot projects in selected hospitals (Honda 2002). JICA has promoted the 5S-Kaizen method application in healthcare in more than 2,000 health facilities in 29 countries (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare 2018).

JICA (2013) argues that a successful implementation of the 5S-Kaizen-TQM method requires a stepwise approach. Namely, the implementation of a project will pursue the five steps:

First: Introduction to 5S

Second: Implementation of 3S (Sort, Set in Order, and Shine)

Third: Implementation of other 2S (Standardize and Sustain)

Fourth: Introduction to Kaizen (Transition from 5S to Kaizen)

Five: Implementation of Kaizen

JICA (2013) points out several critical factors which help the program implementation succeed. The hospital manager should show strong leadership for the reformation and provide the necessary support. The organization members, including doctors, nurses, and technical and clerk staff, willingly share the importance of team building and information sharing. The Quality Improvement Team (QIT) and the Work Improvement Team (WIT), organized with clearly defined roles, maintain activities regularly, keep activity records, and appraise small successes based on predefined performance indicators.

Amid the COVID-19 pandemic crisis, infection prevention control (IPC) within healthcare facilities has become critical. On this urgent issue, JICA recently released the online video titled The Importance of Strengthening IPC with “KAIZEN”—Lessons Learned from Hospital Management in COVID-19 Pandemic. The video points out that “Guidelines for IPC and on-site manuals are not being followed in the workplace. Many factors contribute to this: the shortage of staff, unsanitary environment, and insufficient hygiene facilities. It is reported that even most basic infection control measures in many cases are met with difficulty in practice.” It argues that the 5S-Kaizen-TQM method enhances organizational strength by efficiently organizing the healthcare workplace, identifying the root causes of the problems, and enabling management to secure healthcare resources and provide them to the workplace to respond to various issues.

5 Final Remarks: TQC in Japan–Brazil Relation in the Next Stage

Until the 1980s, Brazilian industrialization had been oriented toward the domestic market and was protected from international competitions. Although competitive pressures were weak in that setting, the QCC activities drew attention in Brazil because it was considered to be the hallmark of the Japanese industry’s competitiveness, which was important to Brazil as it caught up in industrialization. Exporting companies and local subsidiaries of multinationals were the first to deploy QCC. The quality movement was diffused by local business associations, and in some cases JUSE from Japan provided technical assistances as a part of its internationalization aim. The first wave of the QCC boom fell short of expectations because of low volunteerism of workers and weak interest among managers in integrating QCC to the Japanese-style company-wide total quality control (TQC). We noted some inter-cultural issues for such shortcomings, such as the difference in the way of life and corporate administration style and the lack of governmental support. The market liberalization which had begun in the 1990s set the new ground for quality control that was designed to seek competitiveness with relevant involvement of public organizations. The second boom did not materialize because globalization and technological paradigm change which began at that time reduced the relevance of context-specific continuous improvement and interference of human factors in terms of quality.

At present, Brazil uses wider perspectives to capture quality management. By obtaining ISO 9000 s accreditation, firms can show the consistency of their production methods to provide products or services in committed quality. Practice of TQC shows that firms uphold a high standard to meet customer requirements exactly, and to do so they engage in continuous improvement based on statistical evidence in every facet of the organization through management commitment and employee training and education. It has become common sense that these two concepts are not in competition; they are actually complementary and provide external validation of firms’ commitment to quality.

We can notice how the past involvement of Japanese private sector and public organizations influenced the transfer of Japanese-style TQC to Brazil. We first noted a significant adaptation of the Japanese-born model to the Brazilian context. For example, the role of leadership of higher-class management in QCC is more emphasized, while monetary reward systems for employees are introduced to induce company-wide involvement. Second, the quality management movement in Brazil gained a social function because the constant improvement of productivity in each organization helped to create the conditions of sustainable development and better quality of life. This definition justifies the public intervention and support to the quality movement because the benefits are not limited to an individual firm’s profit but also offers relevant positive externality to the society. Third, quality management expanded to non-manufacturing sectors.

Regarding the third point, we paid special attention to two contemporary cases from the state government administration and health care service. They share commonalities as non-manufacturing activities with a strong presence of human factors, sensitivity to public interests, and the use of information technology. Our case studies show that the basic concept of systemic continuous improvement of Japanese-style TQC continue to be relevant.

Thus, we can conclude that, in view of expected high reward to the public interest from promoting quality improvement, international cooperation in quality management in these fields is highly recommended. Sectoral approaches and human resource development will be the target. Since the trade liberalization in the 1990s, Brazilian firms are compelled to pursue competitiveness. However, Brazilian firms sought machine-based productivity and quality gains, instead of human-based paradigm of the Japanese-style TQC. The higher profit from improved productivity and quality tends to be distributed unequally in favor of capital and skilled labor at the expense of unskilled workers. Given the social divide in Brazil based on large income inequalities, the Brazilian society needs to change a direction for human-centered quality jobs where workers receive not only decent returns from quality and productivity improvement but also a higher satisfaction from working with dignity and sense of human capability improvement. For that end, we consider that the Japanese-style TQC has a potential of transforming the concept of the work.

Notes

-

1.

Japan and Brazil established diplomatic relations by the Japan–Brazil Treaty of Amity and Commerce (1895). The contract between Japanese private immigration promotion companies and Brazilian state governments defined Japanese immigration to Brazil, the former recruiting immigrants and chartered a ship, and the latter bearing half of the travel expenses. The Japanese government was initially in a position to supervise immigration companies. Still, the rise of unemployment during the inter-war period and the Great Kanto Earthquake (1924) damage encouraged immigration by subsidizing travel expenses.

-

2.

The national project format is a resource development project jointly funded by Japan and Brazil. A state-owned enterprise supported the Brazilian side, and the Japanese side was a joint venture between a private company and a government-affiliated financial institution. Investment in Cerrado development, Carajás mine development, Tubarão steelmaking, Amazon aluminum, Cenibra pulp-and-paper were in such a form.

-

3.

Akio Morita, the co-founder of Sony, remembered that the opinion of anything marked “Made in Japan” was very poor. He confessed that in the early days “we (Sony) printed the line “Made in Japan” as small as possible” (Morita 1986, p. 77).

-

4.

This can be seen on the Deming Institute’s YouTube channel https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vcG_Pmt_Ny4.

-

5.

To distinguish from Feigenbaum’s original idea of TQC, Japanese engineers called the Japanese system the company-wide quality control (CWQC). Currently, TQC and CWQC are used interchangeably. We adopt TQC to what originally meant CWQC.

-

6.

For example, see Yuki (1988, p. 24). Ishikawa and Hiromatsu (1977) observed Volkswagen’s quality control capabilities in Brazil and said “their efforts lag more than 15 years behind the comprehensive control in Japan”.

-

7.

Humphrey (1993) found that after the introduction of QCC, the employment conditions improved due to employment stabilization and wage increase.

-

8.

Oleg Greshner, former quality assurance executive of the Brazilian affiliate of Johnson & Johnson (São José dos Campos, State of São Paulo), explained that a typical reason for QCC not working well was the lack of interest from the top management in the concept of placing QCC as a part of TQC (Greshner 2014). He also pointed out that McGregor’s (1960) X-theory type managers who tend to control the company by order and enforcement (typically found in Brazil) understand the concept of TQC less than Y-theory type managers who mobilize employees by showing them exciting goals and responsibilities progressively.

-

9.

French, Chinese, Portugese, Spanish, Slovenian, Dutch, and Italian versions were all published at the same time as the English version (Ishikawa 1985).

-

10.

Embraer (São José dos Campos, São Paulo State, then a state-owned enterprise), which develops and manufactures aircraft, also participated in AVCQ. AVCQ invited the JUSE mission represented by Kaoru Ishikawa and held the Japan–Brazil quality management seminar. In 1978, AVCQ invited Joseph Juran from the United States to a top management seminar on QC. According to Yuki (1988), 500 companies were already implementing QCC by 1984. In addition to AVCQ, eight regional organization for the dissemination of QCC were born between the late 1970s and the early 1980s, including the Santa Catarina State Quality Management Association, the Anhanguera Quality Management Association (Campinas, São Paulo State), and the Minas Gerais State QCC Association (now União Brasileira para a Qualidade, UBQ). Claudius D’Artagnan C. Barros, the Head of Quality Control of Embraer in the early 1980s, led the Brazilian Quality Control Circle Union (União Brasileira de Círculos de Controle da Qualidade, UBCCQ), which was inherited by UBQ in 1990 (Ferro and Grande 1997).

-

11.

The Malcolm Baldridge Award was established in 1987, modeled after the Deming Prize of JUSE started in 1951.

-

12.

According to Academia Brasileira da Qualidade (2019), FCAV later specialized in consulting for ISO certification acquisition.

-

13.

Taylorism is the organization of work based on deconstructing production process into a sequence of simple actions and then coordinating them by means of managerial intervention in order to acheive the highest productivity in the least time (Source: https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199599868.001.0001/acref-9780199599868-e-1849).

-

14.

In 2017, the media reported successive false quality claims, data falsification, and inspection fraud in large Japanese companies. Remaining authority to production sites despite weakening company-wide quality control efforts incentivizes cheating on meeting stringent demands such as cost and delivery.

-

15.

Secretaria da Fazenda e Planejamento do Estado de São Paulo.

-

16.

A similar result of productivity increase was reported by Ng et al. (2010) from the Emergency Department of Hôtel-Dieu Grace Hospital in Ontario, Canada, and from a broader application of TPS in Virginal Mason Medical Centre in Seattle, WA (Weber 2006), the Emergency Treatment Center at the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics in Iowa City, IA (Dickson et al. 2008).

References

Bernardino, Lis Lisboa, Teixeira, Francisco, Jesus, Abel Ribero de, Barbosa, Ava, Lordelo, Maurício and Lepikson, Herman A. 2016. “After 20 Years, What Has Remained of TQM?” International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 65–3: 378–400. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPPM-11-2014-0182.

Brasil. 1997. “Ministério da Administração e Reforma do Estado. Programa da Qualidade e Participação na Administração Pública (Program of Quality and Participation in Public Administration)” in Cadernos MARE da Reforma do Estado 4.

Brasil. 2003. Ministério da Fazenda. Secretaria Executiva. Unidade de Coordenação de Programas. Modernização Fiscal dos Estados Brasileiros (Brazilian States’ Fiscal Modernization). Brasília: Ministério da Fazenda.

Brasil. 2018. Ministério do Planejamento, Desenvolvimento e Gestão. Gestão da Qualidade em Serviços Públicos Federais—Resultados Preliminares (Quality Management in Federal Public Services—Preliminary Results). Brasília: Ministério do Planejamento.

Bresser-Pereira, Luiz Carlos. 2002. “The 1995 Public Management Reform in Brazil: Reflections of a Reformer: in Ben Ross Schneider and Heredia, Blanca eds. Re-Inventing Leviathan: The Politics of Administrative Reform in Developing Countries, Miami: North–South Center Press: 89–109.

Carvalho, Ruy Quardros. 1987. Tecnologia e trabalho industrial (Technology and Industrial job). São Paulo: L&PM.

Collins, Kevin F., Muthusamy, Senthil K. and Carr, Amelia. 2015. “Toyota Production System for Healthcare Organisations: Prospects and Implementation Challenges” in Total Quality Management and Business Excellence 26–7–8: 905–918. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2014.909624.

Costa, Luana B. M., Godinho Filho, Moacir, Rentes, Antonio F., Bertani, Thiago M. and Mardegan, Ronaldo. 2017. “Lean Healthcare in Developing Countries: Evidence from Brazilian Hospitals” in International Journal of Health Planning and Management 32–1: E99–E120.

Dahlgaard-Park, Su Mi. 2011. “The Quality Movement: Where Are You Going?” Total Quality Management and Business Excellence, 22–5: 493–516. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2011.578481.

Dertouzos, Michael, Lester, Richard and Solow, Rober. 1989. Made in America: Regaining the Productive Edge. Cambridge. MA: MIT Press.

Dickson, Eric W., Anguelov, Zlatko, Bott, Patricia, Nugent, Andrew, Walz, David and Singh, Sabi. 2008. “Sustainable Improvement of Patient flow In an Emergency Treatment Center Using Lean” in International Journal of Six Sigma and Competitive Advantage, 4–3: 289–304. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJSSCA.2008.021841.

Fernandes, Waldir A. 2011. O movimento da qualidade no Brasil (Quality movement in Brazil). Brasilia: Inmetro.

Ferro, José R. and Grande, Márcia M. 1997. “Circulos de controle da qualidade (CCQs) no Brasil: Sobrevivendo ao ‘modismo’” (Quality Control Circles (QCC) in Brazil: Surviving the Fad). Revista de Administração de Empresas, 37–4: 78–88.

Fillingham, David. 2007. “Can Lean Save Lives?” in Leadership in Health Services, 20–4:231–241. https://doi.org/10.1108/17511870710829346.

Fleury, Afonso. 1995. “Quality and Productivity in the Competitive Strategies of Brazilian Industrial Enterprises” World Development, 23–1: 73–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750X(94)00113-D.

Godoy, José Martins de. 2015. “Perda de conhecimentos em gestão (Loss of Knowledge in Management).” http://www.blogdogodoy.com/2015/05/11/perda-de-conhecimentos-em-gestao. Accessed March 11, 2022.

Greshner, Oleg. 2014. “Reasons why QCCs Do Not Attain Expected Results” in Sasaki, Naoto and Hutchins, David eds. The Japanese Approach to Product Quality: Its Applicability to the West, New York: Elsevier: 93–107.

Harada, Akira. 1984. “Nihonshiki no TQC wo kaigai ni fukyu teichaku saserutameni (For the Dissemination and Popularization of the Japanese Style TQC in Overseas) ” in Hinshitsu Kanri 35–3: 39–41.

Hasegawa, Toshihiko and Karandagoda, Wimal. 2013. “Change Management for Hospitals Through Stepwise Approach, 5S-KAIZEN-TQM.” https://www.jica.go.jp/activities/issues/health/5S-KAIZEN-TQM-02/ku57pq00001pi3y4-att/text_e_01.pdf. Accessed June 4, 2021.

Hiraki, K. 1975. “Brazil ni okeru QC Circle katsudou” (QC Circle Activities in Brazil) in Hinshitus Kanri 26–2: 39–43.

Hirata, H. 1983. “Receitas japonesas, realidade brasilieira” (Japanese Recipes, Brazilian Reality) in Novos Estudos 2: 61–65.

Honda, Shunichiro. 2002. “Inspired by Sri Lankan Practice: Scaling-Up 5S–KAIZEN–TQM for Improving African Hospital Service” in JICA Research Institute ed. Scaling Up South–South and Triangular Cooperation, 107–127. Tokyo: JICA Research Institute.

Hosono, Akio. 2009. “Kaizen: Quality, Productivity and Beyond” in GRIPS Development Forum, Introducing Kaizen in Africa, Tokyo: National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies: 23–37.

Hospital Japonês Santa Cruz. 2021. Aplicação da Ferramenta TPS no Hospital Japonês Santa Cruz, Junho/2021, Internal document provided to the authors.

Humphrey, John. 1993. “Japanese Production Management and Labour Relations in Brazil” in Journal of Development Studies, 30–1: 92–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220389308422306.

Ishikawa, Kaoru. 1985. What is Total Quality Control? The Japanese Way. Hoboken, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Ishikawa Kaoru Sensei Tsuisouroku Henshuu Iinkai (Editorial Committee of the Memory of Doctor Kaoru Ishikawa). 1993. Ningen Ishikawa Kaoru to Hinshitsu Kanri (Ishikawa Kaoru and Quality Control). Tokyo: Union of Japanese Scientists and Engineers Publisher.

Ishikawa, Kaoru and Hiromatsu, Yasuyuki. 1977. “Chunanbei hinshitu kanri chousadan houkoku (2)” (The Second Report of The quality Control Research Mission for Latin America) in Hinshitsu Kanri (Quality Management), 28–4: 33–46.

Izaac Filho, Neder R. 2004. Sistema de compras eletrônicas por leilão reverso: Estudo dos impactos observados na experiência do Estado de São Paulo (Electronic Procurement System by Reverse Auction: Study of the Impacts Observed in the State of São Paulo). Master’s thesis, Escola de Administração de Empresas de São Paulo da Fundação Getúlio Vargas.

JICA. 2013. “Preparatory Survey on the Program of Quality Improvement of Health Services by 5S–Kaizen–TQM—Final report.” https://openjicareport.jica.go.jp/980/980/980_400_12114781.html Accessed June 7, 2021.

Kajita, Takamichi, Tanno, Kiyoto, and Higuchi, Naoto. 2005. Kao no Mienai Teiju-ka: Nikkei Burajiru Jin to Kokka, Shijou, Imin Network (Invisible Residents: Japanese–Brazilians Vis-a-Vis the State, the Market, and the Immigration Network). Nagoya: Nagoya University Press.

Kanamori, Shogo, Shibanuma, Akira and Jimba, Masamine. 2016. “Applicability of the 5S Management Method for Quality Improvement in Health-Care Facilities: A Review” in Tropical Medicine and Health, 44: 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41182-016-0022-9.

King, Ney Cesar de Oliveira, Lima, Edson Pinheiro de. and Costa, Sérgio Eduardo Gouvêa da. 2014. “Produtividade sistêmica: conceitos e aplicações (Systemic Productivity: Concepts and Applications)” in Production 24–1: 160–176. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-65132013005000006.

Kubo, Edson Keyso de Miranda and Farina, Milton Carlos. 2013. “The Quality Movement in Brazil” in Total Quality Management and Business Excellence, 24–1: 19–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2012.704270

Kusaba, Ikuo. 1974. “Brazil no hinshitsu kanri (Quality Control in Brazil)”. Hinshitsu Kanri 25–2: 44–46.

Kusaba, Ikuo. 1984. “Nihon no hinshitsu kanri no kokugai Ten-I” (International Transfer of Japanese Quality Control) in Hinshitsu Kanri, 35–3: 19–22.

Maruyama, Hiroaki. 2010. Brazil Nihon Imin 100-nen no Kiseki (Trajectories of 100 Years of Japanese Immigrants in Brazil). Tokyo: Akashi Shoten.

McGregor, Douglas. 1960. The Human Side of Enterprise. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Miyake, Dario Ikuo. 1996. “The Development of QC in Brazil and the Japanese Style TQC” Hinshitsu, 26–2: 44–49.

Morita, Akio. 1986. Made in Japan: Akio Morita and Sony. New York, NY: E. P. Dutton.

Ng, David, Vail, Gord, Thomas, Sophia and Schmidt, Nicki. 2010. “Applying the Lean Principles of the Toyota Production System to Reduce Wait Times in the Emergency Department” Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine, 12–1: 50–57.

Nihon–Brazil Koryushi Henshu Iinkai (Editorial Committee of the History of Japan–Brazil Exchanges) ed. 1995. Nihon–Brazil Kouryu Shi: Nippaku Kankei 100-nen no Kaiko to Tenbou (History of Japan–Brazil Exchanges: Retrospectives of 100 Years of Japan–Brazil Relation and Future Perspectives). Tokyo: Japan–Brazil Central Association.

Nishimura, Mario. 1984. Brazil ni Okeru Nihon Teki TQC no Eikyou (Influences of the Japanese Style TQC in Brazil). Hinshitsu Kanri, 35–3: 31–34.

Pedrosa, Glauco V. and Menezes, Vítor G. 2019. Pesquisa e modelo de avaliação da gestão da qualidade dos serviços públicos federais: Relatório técnico (Research and Evaluation Model of Quality Management in the Federal Public Services: Technical Report). Brasilia: Universidade de Brasília. Faculdade do Gama.

Pereira, Veruska E. 2012. A melhoria da gestão pública com enfoque na certificação ISO 9001:2008: um estudo de caso na Bolsa Eletrônica de Compras-BEC/SP (Public Management Improvement with Focus on ISO 9001:2008 Certification: A Case Study at the Bolsa Eletrônica de Compras-BEC/SP). Master’s thesis, Programa de Mestrado em Engenharia de Produção, Universidade Nove de Julho.

Pereira, Veruska E., Pereira, Maria A. and Calarge, Felipe A. 2010. “Implementation of the Quality Management System at the Bolsa Eletrônica de Compras do Estado de São Paulo - BEC/ SP: A Case Study Approaching Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Result” in Proceedings XVI International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management.

Saito, Hiroshi. 1960. Ijusha no Idou to Teichaku ni Kansuru Kenkyu (On the Mobility and the Settlement of Japanese Immigrants in Brazil). Kobe: Research Institute for Economics and Business Administration, Kobe University.