Abstract

There is nothing wrong with the NAEP reading exercises, the sampling design, or the NAEP Reading Proficiency Scale, these authors maintain. But adding a rich criterion-based frame of reference to the scale should yield an even more useful tool for shaping U.S. educational policy.

Phi Delta Kappan. 69. 1988

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

In the January 1988 Kappan, Leslie McLean and Harvey Goldstein fired off a vitriolic attack on the design and interpretation of the National Assessment of Educational Progress.Footnote 1 In particular, they attacked the “fictional” properties of the NAEP Reading Proficiency Scale “RPS” and concluded with the bold assertion, “In reality, reading achievement is not unidimensional.”Footnote 2

Remarkably, this conclusion followed a summary of the NAEP's study on the dimensionality of reading, which concluded: “Overall, the four dimensionality analyses of the NAEP reading items indicate that it is not unreasonable to treat the data as unidimensional.”Footnote 3 In addition it should be pointed out that the NAEP spent $150,000 trying to reject the unidimensionality hypothesis for reading,Footnote 4 and this work stands as probably the most carefully designed and skillfully implemented study of its kind in the literature.

For most of this century, debate over the nature of reading comprehension and over the behaviors measured by reading comprehension tests has waxed and waned. Why should such questions be so important? The answers to these questions directly affect the way we measure reading comprehension and the way we teach children to read.

Comprehension testing and reading instruction in this nation have been fragmented into hundreds of objectives, skills, and taxonomies that may well be misdirecting the efforts of reading teachers. The dissection of reading comprehension into a myriad of subskills has been fostered to a great extent by the way reading tests have been constructed. When we examined the reading comprehension tests in widespread use today, we are immediately struck by their diversity. The tests vary greatly in the subskills each claims to measure. By the same token, item formats vary from single sentences or paragraphs too lengthy passages. Some involve pictures; some, cloze responses; and some, separate questions about each passage. The kinds of questions that are asked of a student also appeared to vary, but some of this diversity may be the result of the taxonomies used to catalog these differences.

With the sponsorship of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development “NICHHD”, we conducted a study of 3,000 reading comprehension items appearing on 14 reading comprehension tests, one of which was the NAEP test. Our study asked the question, is there a common dimension being measured by these tests? To examine this question, we used the Lexile theory of reading comprehension,Footnote 5 which states that the difficulty of text can be predicted from knowledge of the familiarity/rarity of the vocabulary used and the demands the text places on short term memory.

For our study we correlated the difficulties of the test items (provided by published norms) with the difficulties of the items (as measured by a computer analysis using the Lexile theory). Table 1 shows the results of our computations, which produced an average correlation of 0.93.

It seems reasonable to conclude from these results that most attempts to measure reading comprehension—no matter what the item form, type of prose, or response requirement—end up measuring a common comprehension factor captured by the Lexile theory. In short, the majority of reading comprehension tests in use today measure a construct labeled “reading comprehension.” Furthermore, it should be evident from Table 1 that the RPS is no more a fiction than our scales derived from the other 13 tests we examined.

The source of McLean and Goldstein’s confusion regarding the NAEP can be traced to a failure to separate what a test measures from the usefulness of a score. By failing to distinguish between what the NAEP Reading Proficiency Scale measures and how useful it is as a communication device, McLean and Goldstein become their own biggest detractors. The important point they raise about the utili-ty of a score is obscured and eventually lost amid a welter of non sequiturs.

Bringing meaning to test scores is the single most important activity that test designers engage in. Two frames of reference for interpreting test scores are generally distinguished: norm referenced and criterion referenced.

A norm referenced framework for score interpretation involves locating a score in a normal distribution; usually that distribution is normed on a national sample, and the result is often expressed as a percentile. This is by far the most common means of imparting meaning to a score, but it has serious defects if used exclusively. Foremost among these defects is that knowing that a student reads at the 80th percentile for fourth-graders nationally does not help a teacher select instructional materials nor does it tell us what the student can or cannot read. The NAEP has done a splendid job of providing a normative frame of reference for reading test scores.

It is on the criterion-referenced side that improvement is both necessary and achievable. The approach to criterion referencing adopted by the NAE P is to equate points along the Reading Proficiency Scale and test items used in the assessment. Thus a score of 250 on the RPS is matched with the test items that students who scored 250 can answer correctly 80% of the time.

Such a strategy for imparting meaning to scores is clearly better than an exclusive reliance on norm referencing. But it is context-bound in that only items used in the assessment can be used in describing what a score at any given level means. What is needed is a method for building a criterion-based frame of reference that is free from the local context of the assessment. Such a frame of reference would enable us to ask, for example, what RPS ability score is required for a student to read a local newspaper with a 75% comprehension rate.

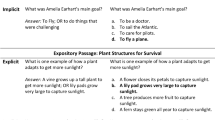

Using Lexile theory, it is possible to construct a scale of the difficulty of “real world” prose encountered by fourth-grade students, high school seniors, or young adults trying to find a job. Test scores can be expressed as the expected comprehension rate for an individual encountering a text with a given predicted “theoretical” difficulty. An example of such a scale is found in Fig. 1.

The works listed in the far right column of Fig. 1 contain representative sample passages that differ in difficulty by 100 Lexile increments. (There are also two anchor titles that are used to establish the extremes of the scale.) These works represent the kinds of prose that individuals with corresponding Lexile scores can read with a 75% comprehension rate. To the right of the scale are bands represent-ing national percentiles for grades 2 through 12.

By juxtaposing the normative and criterion-based frames of reference, it is possible to see what a student with a given ability is able to read. This knowledge pro-vides the teacher with a way to operationalize the meaning of a test score. It can al-so help the teacher place that student in a basal series or to select appropriate supplemental materials. Finally, the criterion reference can provide policy makers with a tool that can be used to answer such questions as the following:

-

What proportion of our nation's fourth-graders can read their fourth-grade basal readers with at least a 75% comprehension rate?

-

What proportion of our nation's high school graduates can read USA Today with at least a 75% comprehension rate?

-

What ability level is required to comprehend warning labels, tax forms, insurance policies, etc.?

In Literacy: Profiles of America’s Young Adults, Irwin Kirsch and Ann Jungeblut note that “the important question facing our society today is not ‘How many illiterates are there?’ but rather “What are the nature and levels of literacy skills demonstrated by various groups in the population?” The question of the levels of skill can be answered by means of the existing norm-referenced frame-work. The question of the nature of those skills, however, requires a rich criterion-based frame of reference.

Thus the policy analyst in Washington, D. C., and the fourth-grade teacher in Omaha both want to know what students can read. A satisfactory answer to this question requires a criterion-based frame of reference that is independent of the as-sessment context. That Lexile framework can yield interpretations of scores in terms of what students can read at various levels of development, and this frame-work can easily be imposed on the existing RPS.

McLean and Goldstein argued that “to have relevance for policy, however, such assessments [as the NAEP] must use measures that are connected to teaching and learning.” We hope that we have made it clear that it is through a criterion-based frame of reference for score interpretation that we link test scores to teaching, learning, and so-called “real-world” tasks.

There is nothing wrong with the NAEP reading exercises and sampling design- or with the RPS. Adding a rich criterion-based frame of reference to the RPS should address the objections of McLean and Goldstein and fashion an even more useful tool for shaping our nation's educational policy.

Notes

- 1.

Leslie D. McLean and Harvey Goldstein, “The U.S. National Assessments in Reading: Reading Too Much into the Findings,” Phi Delta Kappan, January 1988, pp. 369–372.

- 2.

McLean and Goldstein, p. 371.

- 3.

Albert E. Beaton, Implementing the New Design: The NAEP 1983–84 Technical Report (Princeton, N.J.: National Assessment of Educational Progress/Educational Testing Service, Report No. 15-TR20, 1987), p. 273. See also Rebecca Zwick, “Assessing the Dimensionality of NAEP Reading Data,” Journal of Educational Measurement, Vol. 24, 1987, pp. 293–308.

- 4.

Albert Beaton, personal communication, May 1987.

- 5.

A. Jackson Stenner, Dean R. Smith, Ivan Horabin, and Malbert Smith, “Fit of the Lexile Theory to Item Difficulties on Fourteen Standardized Reading Comprehension Tests,” paper presented at the National Reading Conference, St. Petersburg, FL, 1987.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Stenner, A.J., Horabin, I., Smith, D.R., Smith, M. (2023). Most Comprehension Tests Do Measure Reading Comprehension: A Response to McLean and Goldstein. In: Fisher Jr., W.P., Massengill, P.J. (eds) Explanatory Models, Unit Standards, and Personalized Learning in Educational Measurement. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-3747-7_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-3747-7_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-19-3746-0

Online ISBN: 978-981-19-3747-7

eBook Packages: Physics and AstronomyPhysics and Astronomy (R0)