Abstract

This chapter presents a study on the identification and recognition of knowledge, skills and competencies required to convert and maintain green enterprises in a Philippine context and in the light of Philippine policies, legislation and investments to stimulate the development of new green markets. It examines the use of ‘green’ practices in enterprises, the benefits and challenges in the application of such practices, the extent to which respondent micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) have identified the green skills requirements and whether skills recognition mechanisms such as job cards or other portfolio systems have been put in place as part of recognition processes and workplace training programmes. This chapter begins by giving an overview of the Philippine economy and society and the role of MSMEs in four dynamically developing industry sectors namely, automotive, catering, PVC manufacturing and waste management. Given the environmental challenges and problems faced by enterprises in these sectors, the study looks at the extent to which the government’s green job policies, laws, qualifications framework, training regulations and standards address environmental challenges and problems faced by enterprises. The study thus examines connections between macro policies, rules, laws and regulations and micro-level application through practices and green skills and their recognition through recognition mechanisms.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Environmental challenges

- Industries and services

- Green practices

- MSMEs

- Green jobs

- Green skills

- RVA

- Workplace training

- Assessment and certification

- Greening TVET

1 Introduction

A basic premise of the study is that if green skills and green practices are to be promoted and recognised, firms need to understand green skills requirements and the recognition of these skills as an important part of workplace training programmes. There is a lack of interest among micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs) to recognise environmentally friendly practices. However, this could change with the Philippine government’s Green Jobs Act of 2016, which provides tax reduction and other incentives for MSMEs.

Thus, this paper will put an emphasis on the voices of employers, employees and enterprises that are largely absent from analysis and policy-making. It is important to know what workers in MSMEs think and are learning about green skills in their workplaces. Most notably, they reported that increasing changes around green skills are being implemented into both work roles but not equally in training.

The Technical Education and Skills Development Authority (TESDA) through its National Institute for Technical Education and Skills Development (NITESD) conducted the fieldwork for this study. The data considered stakeholder perspectives at all levels. The analysis will begin by studying the national government standpoint in addressing workplace environment-related issues in all sectors, and then move to obtaining insights on frameworks and standards established by government authorities in collaboration with industry associations or trade unions and other private sector agencies. Finally, it will look at green skills inclusion in recognition practices from the perspective of enterprises.

Rationale for conducting the empirical study in enterprises

While policies and environmental laws, as well as green standards, competences and qualifications have been developed, there is little information on whether they are implemented at the level of MSMEs or in promoting cleaner production processes in the workplace. In many MSMEs, workers involved in the everyday practice of production do not comply with new regulations and standards. However, the questions of compliance of environmentally friendly regulations should not only concern managers and executives, rather, compliance should concern each worker. Another neglected issue is non-formal education or workplace learning, which is believed to be the core element in meeting the training needs of workers. The training must be conducted on the job and in the working environment, adapting teaching methods to the learning abilities of workers, as well as addressing the issues of access and costs. The learning process must address the entire value chain to build an understanding of causalities, interdependencies and environmental impacts. Promoting green skills is not only about automation and Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM), but also about tracing compliance with environmental regulations at every step in the production process.

The socio-economic environment and the role of industry sectors

The 2019 International Monetary Fund (IMF) statistics ranked the Philippine economy as the 36th largest in the world (IMF 2019). The Philippines is considered one of the largest emerging markets and fastest-growing economies in Asia. The Philippine economy, which used to be agriculture-based, is transitioning to services and manufacturing. Its gross domestic product (GDP) based on purchasing power parity in 2016 was estimated at around US $304 billion. The primary exports include semiconductors and electronic products, transport equipment, garments, copper products, petroleum products, coconut oil and fruits. Major trading partners include the United States, Japan, the People’s Republic of China, Singapore, the Republic of Korea, the Netherlands, Germany and Thailand.

Box 11.1 The economic contributions of the industry and services sectors

Automotive industry

-

The Philippine automotive manufacturing industry (PAMI)—composed of two core sectors, namely manufacturing of parts and accessories for motor vehicles and the manufacturing of motor vehicles—is one of the major drivers of the Philippine industry, generating approximately P248.5 billion (US$5 billion) sales in 2013;

-

The industry roadmap has targeted 300,000 quality jobs by 2022;

-

The local vehicle manufacturing industry is expected to attract P27 billion (US$500 million) in fresh investments, manufacture 600,000 more vehicles and add P300 billion to the domestic economy (equivalent to 1.7% of GDP). This has the approval of the Comprehensive Automotive Resurgence Strategy (CARS) programme in 2016;

-

The comprehensive operation of the automotive industry extends to other complementary sectors such as textiles, glass, plastics, electronics, rubber, iron and steel. Hence, increasing PAMI’s productivity would likewise increase the economic activity of supporting industries, and the Philippine economy (Palaña 2014).

Catering services

-

As tourism serves as the main market for hotel and restaurant services, the increase in visitor traffic over the past 10 years resulted in a corresponding boom in the catering industry;

-

Catering services include hotels, motels, restaurants, fast food establishments and educational institutions that provide training and other types of organisations responsible for the promotion of hospitality services;

-

Businesses also purchase food, tools and supplies to help their establishments to generate revenue for supporting businesses;

-

The economy is stimulated by employing locals for jobs such as food preparation. In turn, these workers earn wages and become tax payers and contribute to economic growth;

-

The total income in 2012 by the road service (catering) industry reached P267.5 billion (about US$5 billion). More than half of the total income of the Philippines was earned by the National Capital Region (NCR) amounting to P151.6 billion (US$3 billion) (PSA 2012).

PVC manufacturing

-

Polyvinyl chloride (PVC) is a versatile thermoplastic material used in the production of hundreds of everyday consumer products. International and local investments have generated thousands of jobs for Filipinos since 2000.

-

The Philippine Resins Industries, Inc. (PRII) is embarking on a P1.68 billion (US$50 million) expansion of its polyvinyl chloride (PVC) manufacturing plant in Mariveles, Baatan (Ferriols 2001).

Waste management industry

-

The Philippine waste management sector, which has created many jobs, includes the following activities:

-

Water collection, treatment, and supply;

-

Waste removal and disposal services;

-

Formal recovery of recyclable;

-

Informal valorisationFootnote 1 of waste products; and

-

Sewage and remediation activities.

-

-

Output value of the different activities

-

Water collection, treatment and supply: PHP55.1 billion (about US$100 million) (91.1%);

-

Material recovery: PHP2.3 billion (about US$40 million) (3.8%);

-

Waste collection: PHP1.9 billion (about US$33 million) (3.1%);

-

Sewage and remediation activities and other waste management services: PHP0.8 billion (about US$15 million) (1.3%);

-

Waste treatment and disposal: PHP0.4 billion (about US$7.5 million) (0.6%) (PSA 2014).

-

Source: Authors

Formal sector enterprises

Data for formal sector establishments from the 2010 Annual Survey of Philippine Business and Industry (ASPBI) highlighted 148,266 formal sector establishments. In terms of employment, data collated by TESDA indicates that waste management had the highest employment figures at 47,176 people, followed by manufacturing at 41,528, automotive at 18,337 and catering at 7,479 people. However, many jobs are precarious or casual and operate on a contractual basis. Not all these jobs are salaried; often they are contractual (PSA 2010). Thus, despite considerable industrial development in the country, there are major income and growth disparities between the country's different regions and socio-economic classes. The challenges facing the government are high poverty incidence (33% of the population), increased unemployment rate (6.3% of the active population), and persistent inequality in wealth distribution (PSA 2014).

There are several challenges that come with greening the economy. Since 1990, the Philippines has seen significant growth in the services sector (55% of the labour force market), followed by agriculture (29%) and manufacturing/ industry (16%) (Central Intelligence Agency 2017). Thus, more green practices in the service sector are particularly important to address.

Challenges to achieving more inclusive growth remain. Even though the economy has grown and the unemployment rate has declined somewhat in recent years, it remains high at around 6.5%; underemployment is also high, ranging from 18 to 19% of the employed. At least 40% of the employed work in the informal sector (Central Intelligence Agency 2017). This means that most of the people working in the informal sector have achieved their skills through informal or non-formal education and training while on the job or outside the workplace.

Environmental challenges and national policy responses

Environmental challenges

The World Health Organization (WHO) reported that seven million people worldwide die annually from air pollution—over six million of them were recorded in Asia. Most of these cases are in the People’s Republic of China and India, but experts warned that the Philippines might not be far behind (Montano 2016). The Philippines is affected by the increasing density of air pollutants, particularly in cities caused by emissions from vehicles and factories; non-compliance of environmental standards; and incineration (Congress of the Philippines 1990). Incineration is defined as the burning of municipal, biomedical and hazardous wastes whose process emits toxic and poisonous fumes. Industry and enterprises are contributing greatly to these environmental hazards.

The increasing volume of household, commercial, institutional, and industrial wastes is an increasing concern. A single resident in Manila produces an average of 0.7 kg of waste a day, about 130% higher than the global average of 0.3 kg per person per day. According to the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR), Metro Manila alone produced about 8,400 to 8,600 tonnes of trash per day in 2011. In addition, street sweeping, construction debris, agricultural waste and other non-hazardous/non-toxic waste products continued to pile up in many areas of the country. The lack of strict public compliance and enforcement powers of those in authority were identified as factors for improper waste management. Other salient issues related to the collection and segregation of solid wastes and monitoring of solid waste management.

Another pressing environmental challenge is the worldwide six-fold increase in consumer good production and subsequent increase in global waste generation by 900% since the 1990s according to the World Trade Organization (WTO). However, due to high costs, developed countries could only recycle 11% of their waste.Footnote 2 The rest were exported to developing countries like the Philippines, where environmental laws were weak and where these toxic and hazardous wastes were accepted as additional livelihood opportunities. In addition, the technological revolution has given rise to a new and growing form of toxic and hazardous waste, e-waste (waste electrical and electronic equipment or WEEE), a consequence of the prodigious growth in the number of computers, cell phones and electronic gadgets that started in the 1990s. The Philippines has continued to be one of the leading destinations for chemical products and toxic substances from developing countries and has become one of the leading importers of ‘persistent organic pollutants’ (POPs), which continually pollute agricultural lands and poison the rivers, lakes, and seas (Ilagan et al. 2015).

National policy responses to environmental challenge

The leading role of the government in terms of greening has been highlighted by researchers (e.g. Pavlova 2016). The Philippines is a good example. Several governmental policies address environmental challenges. The Philippines addressed its plans for a greener future in the 1990 Philippine Strategy for Sustainable Development (PSSD) supplemented in 2004 with the Enhanced Philippine agenda (EPA) 21. In the Philippine development plan (PDP) 2011–2016, the conservation, protection and rehabilitation of the environment and natural resources were highlighted (Baumgarten and Kunz 2016).

Administrative order No. 17 issued by the DENR in 2002 provides the national policy context for the analysis of skills for sustainability and the greening of the economy and society. A major authority for the implementation of environmental policies is the Environmental Management Bureau (EMB) (Department of Environment and Natural Resources 2002).

Box 11.2 Philippine environmental legislation

National laws were enacted in four broad areas.

-

1.

Republic Act 6969—Toxic Substances and Hazardous and Nuclear Wastes Control Act of 1990 provides for a legal framework to control and manage the importation, manufacture, processing, distribution, use, transport, treatment and disposal of toxic substances and hazardous and nuclear wastes. The law prohibits, limits, and regulates the use, manufacture, import, export, transport, processing, storage, possession, and wholesale of priority chemicals that are determined to be regulated, phased-out, or banned because of the serious risks they pose to public health and the environment. The swelling issues of industrial waste, proliferation and waste dumping in the Philippines prompted the implementation of this Act (Congress of the Philippines 1990).

-

2.

Republic Act 8749—Philippine Clean Air Act of 1999 provides a comprehensive air quality management policy and programme that aims to achieve and maintain cleaner air for all Filipinos. The law covers all potential sources of air pollution: (1) mobile sources such as motor vehicles; (2) point or stationary sources such as industrial plants; and (3) area sources such as wood or coal burning. Gas/diesel powered vehicles on the road will undergo emission testing, and violators will be subjected to penalties. The law also directs the complete phase-out of leaded gasoline; lowering the sulphur content of industrial and automotive diesel; and lowering aromatics and benzene in unleaded gasoline. All stationary sources must comply with the National Emission Standards for Source Air Pollutants (NESSAP) and National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) and must secure their permission to operate, prior to operations (Congress of the Philippines, 1999).

-

3.

Republic Act 9003–Ecological Solid Waste Management Act of 2000 provides for a legal framework for the country’s systematic, comprehensive, and ecological solid waste management programme that shall ensure the protection of public health and the environment. Under this law, there are several provisions to manage solid wastes (SW) in the country: (1) Mandatory segregation of SW to be conducted at the source; (2) Systematic collection and transport of wastes and proper protection of garbage collector’s health; (3) Establishment of reclamation programmes and buy-back centres for recyclable and toxic materials; (4) Promotion of eco-labelling and prohibition on non-environmentally acceptable products and packaging; and (5) Prohibition against the use of open dumps and establishment of controlled dumps and sanitary landfills, among others (Congress of the Philippines, 2001).

-

4.

RA 9275–Philippine Clean Water Act of 2004 deals with poor water quality management in all surrounding bodies of water, pollution from land-based sources and ineffective enforcement of water quality standards. It also tackles improper collection, treatment, and disposal of domestic sewage, and wastewater charge systems (Congress of the Philippines, 2004).

Source: Authors’ compilation based on the Congress of the Philippines legal enactments

2 Terminology and Definitions

Republic Act (RA) 10,771, otherwise known as the Philippine Green Jobs Act of 2016, is the country’s legal mandate for promoting green economies amongst enterprises. The law also grants business incentives, such as special tax deductions from their taxable income and duty-free importation of capital equipment on top of the fiscal and non-fiscal incentives already provided for by existing laws, orders, rules and regulations of the government to encourage them to help generate and sustain ‘green jobs’ (Department of Labour and Employment 2017).

The law defines ‘green jobs’ as employment that contributes to preserving or restoring the quality of the environment, be it in the agriculture, industry or the services sector. ‘Green jobs’ shall produce ‘green goods and services’ that would benefit the environment or conserve natural resources. The Law envisions a ‘green economy’ which is low-carbon and resource-efficient, resulting in improved human well-being and social equity in the reduction of environmental risks and ecological scarcities.

The Philippine Development Plan (PDP) 2011–2016 (NEDA 2014) stipulated that green jobs can exist and flourish in all sectors. Green jobs can be found where there are measures taken to: (1) introduce low-carbon policies; (2) adapt to climate change; (3) reduce resource use and energy; and (4) protect biodiversity. The plan prioritised key areas identified as mainstream activities affected by climate change: agriculture, fisheries, forestry, energy, construction, transport (including automotive), manufacturing (including PVC production), services (including catering), tourism and waste management.

The pilot application of ‘Policy guidelines on the just transition towards environmentally sustainable economies and societies for all’ that is being conducted in three countries, including the Philippines, adopted by the ILO Governing Body in October 2015, enables the government, together with employers, workers, organizations and other stakeholders, to leverage the process of structural change towards a sustainable, low-carbon, climate-resilient economy to create decent jobs on a significant scale (ILO 2017).

The Philippines adopts the Cedefop notion of ‘green skills’ defined in terms of the technical skills, knowledge, values, and attitudes needed in the workforce to develop and support sustainable social, economic, and environmental outcomes in business, industry and the community.

Stakeholder involvement in green skills development in the Philippines

Several stakeholders are responsible for implementing the Green Jobs Law. Green jobs and green skills are being promoted through several departments: the Department of Labour and Employment (DOLE) for formulating the National Green Jobs Human Resource Development Plan (NGJHRDP) on the development, enhancement and utilisation of the labour force; the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) to establish and maintain a climate-change information management system and network; the National Economic and Development Authority (NEDA) for ensuring the mainstreaming of green jobs concerns in the development plans; the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) for developing a special business facilitation programme for enterprises; the Department of Transportation and Communications (DOTC) to encourage more investments in public infrastructure and services that foster green growth; the Climate Change Commission (CCC) for developing and administering standards for the assessment and certification of green goods and services of enterprises; and the Department of Finance (DOF) to administer the grant of incentives to qualified enterprises. In relation to the education system, three entities are responsible for implementing respectively green standards, the green curriculum and green skills. These are the Department of Education (DepEd), the Commission on Higher Education (CHED) and TESDA. In addition, the Professional Regulation Commission (PRC) is responsible for facilitating the recognition of knowledge, skills and competency of professionals working in the green economy. The TESDA, the DOLE, and the Department of Science and Technology (DOST) will also analyse skills, training and retraining needs in relation to the use of green technology that has the potential to create new green occupations.

Meanwhile, the DTI, which has promoted the three-year Green Economic Development (ProGED) Project jointly with the GIZ of Germany since January 2013, aims to enhance the competitiveness of MSMEs by helping them adopt climate-smart and environmentally friendly strategies through a value chain approach (Silva 2016).

Challenges of greening TVET

TVET has been called upon to make a pivotal contribution to the national goals of inclusive growth, poverty reduction and greening of skills in the context of the Third cycle (2011–2016) of the National Technical Education and Skills Development Plan (NTESDP) anchored on the PDP. Under Strategic Direction 15, TVET needs to ‘develop and implement programmes intended for green jobs.’ This is pursued through the development of new training regulations (TRs) or amendment/ review of existing TRs for green jobs and sustainable development, including agro-forestry, developing the capacity of trainers and administrators to implement ‘green skills’ programmes and linking-up with local and international agencies in the design, implementation and monitoring of ‘green skills’ programmes. (www.tesda.gov.ph). TESDA is responsible for formulating the necessary TRs for the implementation of skills training, programme registration and assessment, and certification in support of the requirements for skilled manpower for the ‘green economy’ (Department of Labour and Employment 2017).

TVET plays a crucial role in enhancing workers’ productivity and employability and facilitates the active and meaningful participation of workers in the development process. The plan highlighted strategies that will address issues pertaining to innovation and the greening of skills. Most of all, TVET will be responsible for mitigating the effects of climate change in the world of work and workplaces. In this regard, TVET has the aims of (1) ‘greening’ existing jobs to meet the current demand for retrofitting and the retooling of the industry to ensure that existing industries continue to grow; and (2) training new workers with the appropriate green skills particularly for the renewable industries and emergent ‘green’ technology sectors. The challenge, therefore, is to strategise environmental education and skills development in anticipation of a green shift in the priority sectors that include agriculture, forestry, fishery, manufacturing (electronics and automotive) services, solid waste and waste water management, energy, transportation and construction (based on the draft NGJHRDP of DOLE 2017).

TVET has a big role to play to support the government policy of protecting and caring the environment. New competences need to be developed relevant to this concern. Going into ‘green jobs’ will require the retooling of skilled workers in sectors with high environmental impacts.

The status of the recognition of green skills

In the Philippines, recognition, validation and accreditation of learning outcomes and competencies of workers in enterprises (i.e. in non-formal learning) is one of the components of competency-based TVET and is part of the strategic directions of the National TESD Plan 2005–2009 (NTESDP) (www.tesda.gov.ph). As of December 2017, TESDA had 33 qualifications/TRs out of 2589 promulgated TRs covering environment-related knowledge, skills, and attitudes in the TRs and curricula. In catering services, automotive, PVC manufacturing and waste management sectors, 5S (sort, set in order, shine, standardise and sustain) and 3Rs (reduce, reuse, recycle) are included in the required knowledge and skills which were considered ‘green’. The 5S methodology is also a ‘must’ for all TVET trainers. TESDA likewise amended the TRs for automotive servicing NC III to include LPG conversion and repowering in the set of competences to promote cleaner emissions of vehicles. Ship’s catering takes precautions to prevent pollution in the marine environment by implementing waste management and disposal systems. See Table 11.1 for the list of TESDA TRs with a ‘green’ outlook related to the four industries.

TESDA also conducted a training programme in collaboration with the Department of Energy (DOE) to integrate the use of energy-efficient lighting in the TR for electrical installation and maintenance qualifications. All the qualifications with a green outlook have been accommodated in the Philippine Qualifications Framework (PQF). The Competency Standards are aligned with the PQF, a national policy describing the levels of educational qualifications and setting the standards for qualification outcomes. It is competency-based and labour market driven. It consists of eight levels of education and training that encourage lifelong learning to allow individuals to start at the level that suits them and then build-up their qualifications as their needs and interests develop and change over time (www.gov.ph). The Philippine TVET Qualification and Certification System (PTQCS), consistent with the PQF, has five different levels of complexity across the three different domains. The qualification levels under PTQCS start from NC I to Diploma.

Development of green qualifications

In accordance with international requirements, TESDA developed qualifications related to refrigeration and air-conditioning. This was done in partnership with DENR and practitioners as part of the national CFC phase-out plan and in accordance with the Montreal Protocol and the Clean Air Act. Through the TESDA training regulations (TRs) on the refrigeration and air-conditioning (RAC) sectors, competences for technicians are identified and addressed during training programmes on recovery, recycling, and retrofitting of RAC systems, which are major sources of ozone-depleting CFCs. In line with this, a code of practice (COP) for RAC was developed by the project with some funding from the World Bank and the Government of Sweden. The TRs promote safety parameters for workers, customers, tools/equipment, and most importantly environmental concerns.

The competency standards of the PQF follow the ILO Regional Model of Competency Standards (RMCS), which prescribes three types of competences, namely: (1) basic competences all workers in all sectors must possess; (2) common competences workers in a sector must possess; and (3) core competences workers in a qualification must possess. Environmental concerns/ concepts are integrated into the basic competences of the TRs. The three learning domains of the competency standards are aligned to the principles of lifelong learning: learning to live together, learning to be, learning to do, and learning to know, as well as to the twenty-first-century skills.

Inviting experts from industry to develop training regulations

TESDA invites experts from industry and/or industry associations who follow guidelines and procedures on how to align each unit of competency to the PQF descriptors. The TRs have four major parts: (1) description of the qualification and job title; (2) competency standards, including the basic, common and core competences; (3) training standards; and (4) national assessment and certification arrangements.

The competency-based TVET (CBT) system recognises various delivery modes in different learning settings – both on- and off-the-job – if CBT specified by the industry drives the training. TVET has developed three delivery modes: (1) Institution-based, which delivers training programmes in public and private TVET institutions, including regional, provincial, and specialised training centres; (2) Enterprise-based, which implements training programmes within enterprises/firms; and (3) Community-based, which delivers training programmes at the local/community level, mostly in partnership with LGUs and NGOs.

Assessment and certification

For every unit of competency that is completed by a learner during training, a certificate of training achievement is awarded, and after completing all the required units of competency, he/she is awarded with a Certificate of Training. The latter indicates the title of the course, the qualification level according to the PQF descriptors, and the units of competency that the learner has acquired. The attainment of each unit of competency is pre-conditioned on the attainment of specific learning outcomes as described in the competency standards. As a prerequisite for graduation, a learner undergoes the national competency assessment, and he/she is given a certificate of competency (COC) after satisfactorily demonstrating competence in a cluster of units of competency or a national certificate (NC) after satisfactorily demonstrating all units of competency comprising a qualification using the assessment criteria provided by the TR/CS computed by an accredited competency assessor.

Assessment and certification also include the recognition, validation, and accreditation of competences and learning and work experience. This system observes two major principles: (1) competency assessment to collect evidence relative to a unit or cluster of units of competency, and (2) RPL to give recognition to an individual’s skill, knowledge, and attitudes acquired through previous training, work, or life experiences.

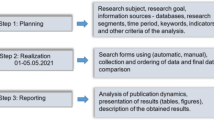

3 Methodology of Primary Data Collection

The study adopts the overall methodology developed by the project for all participating jurisdictions and used the developed instruments such as survey/interview questions, the observation list and the list of generic green skills to collect data (see Chap. 1). This country study reflects results from 29 of 32 enterprises (targeting eight companies in each sector). The study was confined within the National Capital Region (NCR) or Metro Manila, given that in this area there were enterprises representing the four targeted industries (catering, automobile, PVC and waste management). Of the 29 respondent firms, seven were from the automotive industry, six from PVC manufacturing, eight from catering services and eight from waste management. Sixteen enterprises from the formal sector were interviewed and five from the informal sector. Given the limited size of the sample, the study does not pretend to generalise across the four industries. It is exploratory in nature and draws on preliminary insights into the recognition and development of greener skills in the identified industry sectors.

Box 11.3 General information on the enterprises

-

Enterprises in waste management undertook testing of used oil and waste products; microbiological and mechanical testing; verification and certification of public and private firms; and buying and selling recyclable materials such as plastics, meats and paper products.

-

Enterprises in automotive services and sales undertook servicing of new vehicles and restoration and sale of used vehicles.

-

Catering services included food delivery, fast food restaurants, stalls and eateries.

-

PVC enterprises included the sale and installation of plastic pipes and piping systems.

Source: Authors

4 Results and Discussion

Educational attainment of the employees

Analysis of the educational attainment of 1,490 employees in the 29 firms showed that overall, the four industries displayed a very high level of education of personnel—81% of employees across all sectors had higher education, 9–10% had attained a secondary education and TVET qualification, and only 1% was below secondary. Enterprises in PVC manufacturing had 92% (454 out of 495) of their employees with a higher education qualification, followed by waste management, 78% (415 out of 529), automotive industry 76% (296 out of 391) and catering services, 55% (41 out of 75).

Environmentally friendly practices in the enterprises

On the question, ‘What environmentally friendly practices enterprises are followed?’ only 11 (42%) out of 26 respondent enterprises had ‘green jobs’ such as waste water management, renewable energy, energy saving and pollution minimisation. Waste management firms ranked the highest, with seven out of seven respondent enterprises attesting to having such ‘green jobs’, whereas only two of the four firms in PVC manufacturing claimed to have ‘green’ jobs and only one out of seven automotive enterprises had ‘green’ jobs. Only one out of the eight catering enterprises had ‘green jobs’. However, environmentally friendly practices were not only restricted to green jobs. This became clear when firms were asked about the various practices, illustrated in Table 11.2, reflecting environmental sustainability at work in the four industries.

Promoting green practices

Respondents were asked to give their perceptions on how much importance they attached to the theme of green skills in their enterprises on a scale of 1 to 10, where 1 meant low consideration and 10 meant high consideration to these issues. Twenty-five out of 29 responses fell under the scale of 6–10. Four enterprises answered between scales 2–5. However, while high importance is placed on ‘green skills’, there is only a modest promotion of the required skills for the implementation of environment-friendly practices as illustrated in Table 11.3. PVC enterprises employed the highest number of methods for promoting green skills.

Skill requirements for the implementation of environmentally friendly practices

Enterprises in the four industries described important green skills required for the daily operations undertaken by employees (Table 11.4).

How do the respondents acquire their skills?

The employees in the 29 firms across the four industries acquired their green skills in a variety of ways. Both the automotive and PVC manufacturing enterprises identified all the contexts of acquisition. In the catering services and waste management, employees acquired their skills predominantly through self-directed training (seven out of eight) and three out of five respectively (Table 11.5).

Benefits of practising green jobs and skills

On the question of whether including green skills in RVA mechanisms could be beneficial, responses from 25 firms showed that 36 per cent of respondents expected the recognition of green skills to be beneficial for enterprises. They said that it could improve productivity and make enterprises more competitive. On the other hand, 32 per cent of these enterprises expected green skills recognition to benefit the individual in strengthening confidence and motivation, and in promoting core generic skills, social inclusion, higher earnings and better career prospects. Another 32 per cent highlighted benefits for the country by recognising skills that are environmentally friendly.

The benefits of green practices and green skills were also confirmed by a 2012 survey conducted by the Employers Confederation of the Philippines (ECOP) in collaboration with ILO (ECOP & ILO, 2012) covering three areas (NCR, Cagayan De Oro, and Cebu) in the Philippines. Forty-three participants, representing enterprises from manufacturing, food and beverage, land development and real estate enumerated benefits at the level of enterprise, individuals and the nation (Table 11.6).

Reasons for not having ‘green’ jobs with ‘green’ practices

This study also examined the reasons for not adopting green practices. The background research by the ECOP and ILO (2012) pointed out the disadvantages of adopting green projects. They were:

-

Restrictive in terms of the permitted practices (38 per cent of survey respondents);

-

Threat of reducing the profit (25 per cent);

-

Causing job loss (13 per cent);

-

High start-up costs to implement initially (13 per cent);

-

Risk of business shut-downs (13 per cent).

The participants of that project further elaborated that, aside from financial considerations, there is also a lack of awareness and expertise in the Philippines on climate change, environmental issues and green jobs. Additional and appropriate financial and technical support is needed to shift towards green initiatives or launch environmentally friendly practices.

The current study revealed the following reasons why some enterprises did not have green jobs or green practices:

-

Lack of oversight due to sub-contracting especially in waste management and automotive, where a lot of jobs are outsourced to external contractors;

-

Lack of money to buy expensive equipment. This was mentioned by enterprises in the automotive and PVC manufacturing sectors;

-

Presence of policies (i.e. city ordinance) that prohibit the use of environmentally harmful materials, such as plastics, in the case of the catering sector.

Mechanisms for recognising skills, prior learning and work experience in the enterprises

Awareness of RVA frameworks

Very few firms (both employers and employees) said they were aware of the existence and use of RVA frameworks. Only two (1.67 per cent) of 120 respondents said they had heard of frameworks such as the Philippine Qualifications Framework, or other competency-based training frameworks or guidelines prepared by DENR. Only one (0.83 per cent) respondent was aware of a framework developed for human resource development.

Methods used to assess green skills

Only seven out of 30 total responses on methods used to assess green skills alluded to having a job-card system in which employees’ skills were documented. The identified green skills were in waste segregation and disposal, energy conservation, and knowledge of environmental laws such as the Clean Air Act and recycling, among others. In terms of the different sectors, six respondents highlighted the use of different methods, as illustrated in Table 11.7.

The green skills that are not assessed include: the theoretical understanding of green practice; research and development; waste disposal and familiarity with hazardous waste products.

Enterprises did not have a systematic use of RVA mechanisms, in the absence of which, four respondents stated, the use of ad hoc examples such as ‘mentoring’, coaching and apprenticeships acted as approaches to RVA.

Vision for green skills recognition as part of workplace training

Most of the respondents in the four industry sectors talked about their enterprises’ increasing initiatives to implement ‘green’ training programmes for protecting the environment:

Box 11.4 Importance of green training programmes for protecting the environment

Automotive sector

-

Upgrading automotive technology to meet the demand for fuel efficiency and reduce emissions;

-

Providing green customer services;

-

Learning to use eco-friendly equipment and materials.

Catering services

-

Important for recognising green skills;

PVC manufacturing

-

Updating existing training manuals;

Waste management

-

Promoting sanitation standards;

-

Promoting the systematic collection of waste;

-

Promoting more programmes and incentives at the international level;

-

Promoting compliance with governmental efforts and standards (i.e. DENR and Laguna Lake Development Authority).

Source: Authors

Prospects of staff training and RVA

In September 2017, the Implementing Rules and Regulations (IRR) for the Philippine Green Jobs Law was signed. Clearly, the potential for the inclusion of the green skills in RVA is great, not only at the macro level but also at the individual level. Enterprises made suggestions on the prospects of improving skills training and RVA as shown in Table 11.8. Only 12 (41.38 per cent) out of 29 firms cited recommendations for the inclusion of green skills in RPL. All recommendations called for staff training programmes.

5 Conclusions and Recommendations

This chapter, based on research conducted by TESDA, has examined issues pertaining to skills recognition as a tool to improve the environmental and sustainable development in the four industry sectors, namely, automotive, catering services, PVC manufacturing, and waste management.

The Green Jobs Law of 2016 has been pivotal in the increase of green jobs and green practices in enterprises participating in this research. Most of the enterprises remarked on the absence of jobs specifically dealing with green practices before the promulgation of this law. Despite this, a huge majority of these firms observed several practices reflecting environmental sustainability in the workplace, such as waste segregation, waste management disposal, and compliance with environmental rules. The importance given to the topic of green skills and environmentally friendly practices is high, especially in the catering sector. However, the promotion of required skills for the implementation of environment-friendly practices is still modest and there is low utilisation of strategies such as the use of brochures and events, innovations, and incentives for cleaner products/ services and marketing.

Interestingly, employers perceived that the creation of green jobs would lead to improved competitiveness of workers, promotion of decent jobs, and additional employment. Some of them, however, cited disadvantages such as a reduction in profit, and increased costs related to the financial and technical support of green initiatives.

Assessment of RPL in some enterprises involves the verification of certificates. In other enterprises, documentation is undertaken with a job-card system while the certification of RPL is carried out by government agencies (e.g., some environmental authority), the mother company, or training institutions.

Employees’ green skills included technical, cognitive, intrapersonal and interpersonal skills. Employers appreciated the cognitive skills of their employees, the most prominent of which were environmental awareness and willingness to undertake green practices. However, both intra-personal and inter-personal competences registered low appreciation from the employees participating in the research.

The enterprises were not knowledgeable about the national RPL framework, and this was evident given the low utilisation of learning outcomes described in the Philippines Qualifications Framework, competency-based training, HRD frameworks and guidelines designed by the EMB-DENR.

A small number of these enterprises have mechanisms to recognise/assess existing green skills that employees acquire in the workplace, community, or through non-formal education and training programmes. There is no systematic use of RPL; rather, RPL is based on ad hoc examples such as mentoring, coaching and apprenticeship.

It was found that employers used simple methods of RPL assessment (i.e. self-evaluation and interview). Through such methods, employers noticed gaps and deficits in the green skills of workers. The areas where these gaps were most prominent were research and development, waste disposal and familiarity with hazardous waste products, among others.

Most workers acquired their skills non-formally or informally through self-directed learning or on the job or in-company training. Only a few workers had acquired their skills through initial and continuing vocational education and training.

Enterprises believed that green skills had a great potential if enterprises, associations and organizations would support their inclusion in RPL mechanisms. Green skills inclusion in RPL needs to be complemented by other elements such as awareness raising, efficient information dissemination, and technical and financial assistance. Such support activities must be implemented through governmental and societal support.

Factors, in order of prominence, contributing to the effective inclusion of green skills in RVA include: laws/ government policies; business opportunities; environmental and economic realities; support/funding/incentives from the government; international conventions; strong LGU enforcement. All these factors are predicated upon sustained information, education and communication (IEC) actions; advocacy; and social marketing.

The passage of the Green Jobs Law, which provides incentives and tax and duty-free importation of capital equipment, makes the potential for green skills inclusion in recognition in the Philippines realisable.

This study, which includes the participation of seven other Asian countries and one Asian territory, should provide valuable inputs in designing and implementing rules and regulations for the recently enacted Green Jobs Law in the Philippines. Specifically, the mechanisms in the identification of green jobs and the attendant green skills leading to the design of training and assessment and certification of programmes should investigate the different models, not only from the Philippines, but also from the international community.

International development organizations can strategically support the development and distribution of learning/ instructional materials – preferably with formats – that can be shared to facilitate massive and immediate learning to benefit the developing economies and the micro-enterprises of/ in the informal sector.

Notes

- 1.

Individual, family, micro-, small-, and medium enterprises that extract valuable materials from the waste system and valorise them for own use, repair and sale, fabrication, or recycling.

- 2.

The figure pertains only to the US because of unavailability of global data, and given that the US is the biggest producer of industrial waste, this figure is taken as some kind of watermark for all other industrialized countries for purposes of this study (see E. Stewards at http://e-stewards.org/learn-more/for-consumers/effects-of-e-waste/who-gets-stepped-on/).

Abbreviations

- 3R:

-

Reduce, Reuse, and Recycle

- 5S:

-

Sort, Set in order, Shine, Standardize, and Sustain

- ASEAN:

-

Association of Southeast Asian Nations

- ASPBI:

-

Annual Survey of Philippine Business and Industry

- BOI:

-

Board of Investment

- CARS:

-

Comprehensive Automotive Resurgence Strategy

- CBT:

-

Competency-based TVET

- CEDEFOP:

-

Centre Européen pour le Développement de la Formation Professionnelle

- CHED:

-

Commission on Higher Education

- CMU:

-

Compact Mobile Unit

- COC:

-

Certificate of Competency

- COP:

-

Code of Practice

- CS:

-

Competency Standards

- DENR:

-

Department of Environment and Natural Resource

- DepEd:

-

Department of Education

- DOE:

-

Department of Energy

- DOLE:

-

Department of Labour and Employment

- DOLE:

-

Department of Public Works and Highways

- DOST:

-

Department of Science and Technology

- DOT:

-

Department of Tourism

- DOTC:

-

Department of Transportation and Communication

- DTI:

-

Department of Trade and Industry

- ECC:

-

Environmental Compliance Certificate

- ECOP:

-

Employers Confederation of the Philippines

- EMB:

-

Environmental Management Bureau

- EPA:

-

Enhanced Philippine Agenda 21

- GDP:

-

Gross Domestic Product

- GODP:

-

Green Our DOLE Programme

- IEC:

-

Information, Education, and Communication

- ILO:

-

International Labour Organization

- IMF:

-

International Monetary Fund

- IRR:

-

Implementing Rules and Regulations

- IT:

-

Information Technology

- LGU:

-

Local Government Unit

- LLDA:

-

Laguna Lake Development Authority

- LPG:

-

Liquefied Petroleum Gas

- MSMEs:

-

Micro, Small, and Medium-Sized Enterprises

- NAAQS:

-

National Ambient Air Quality Standards

- NC:

-

National Certificate

- NCR:

-

National Capital Region

- NEDA:

-

National Economic and Development Authority

- NESSAP:

-

National Emission Standards for Source Air Pollutants

- NGO:

-

Non-governmental Organization

- NITESD:

-

National Institute for Technical Education and Skills Development

- NTESDP:

-

National Technical Education and Skills Development Plan

- OECD:

-

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development

- PAMI:

-

Philippine Automotive Manufacturing Industry

- PDP:

-

Philippine Development Plan

- PHP:

-

Philippine Peso

- POPs:

-

Persistent Organic Pollutants

- PQF:

-

Philippine Qualifications Framework

- PRC:

-

Professional Regulation Commission

- PRII:

-

Philippine Resins Industries, Inc.

- ProGED:

-

Promotion of Green Economic Development

- PSA:

-

Philippine Statistics Authority

- PSSD:

-

Philippines Strategy for Sustainable Development

- PTQCS:

-

Philippine TVET Qualification and Certification System

- PVC:

-

Polyvinyl chloride

- RAC:

-

Refrigeration and Air Conditioning

- RMCS:

-

Regional Model of Competency Standards

- RPL:

-

Recognition of Prior Learning

- RVA:

-

Recognition, Validation, and Accreditation

- SW:

-

Solid Waste/s

- TESDA:

-

Technical Education and Skills Development Authority

- TMP:

-

Toyota Motor Philippines

- TRs:

-

Training Regulations

- TVET:

-

Technical Vocational Education and Training

- UN:

-

United Nations

- UNEP:

-

United Nations Environment Programme

- WEEE:

-

Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- WTO:

-

World Trade Organization

References

Baumgarten, K. and Kunz, S. 2016. Re-thinking greening TVET for traditional industries in Asia – the integration of a less-skilled labor force into green supply chains. K to 12 Plus Project, Manila. [online] TVET@Asia, 2016, p. 31. Available at: www.k-12plus.org/index.php/news1/220-re-thinking-greening-tvet-for-traditional-industries-in-asia-the-integration-of-a-less-skilled-labour-force-into-green-supply-chains[Accessed 24 June 2018].

Central Intelligence Agency. 2017. Philippines economy 2017: International trade administration. [online] In: CIA World Factbook and Other Sources. CIA, Washington, DC. Available at: www.theodora.com/wfbcurrent/philippines/philippines_economy.html [Accessed 24 June 2018].

Congress of the Philippines. 1990. An act to control toxic substances and hazardous and nuclear wastes, providing penalties for violations thereof, and for other purposes. [online] Available at: http://119.92.161.2/laws/toxic%20substances%20and%20hazardous%20wastes/ra6969.PDF [Accessed 24 June 2018].

Congress of the Philippines. 1999. An act providing for a comprehensive air pollution control policy and for other purposes. [online] The Lawphil Project 1999. Available at: www.lawphil.net/statutes/repacts/ra1999/ra_8749_1999.html [Accessed 24 June 2018].

Congress of the Philippines. 2001. An act providing for an ecological and solid waste management program, creating the necessary institutional mechanisms and incentives, declaring certain acts prohibited and providing penalties, appropriating funds therefor, and for other purposes. [online] The Lawphil Project 2001. Available at: www.lawphil.net/statutes/repacts/ra2001/ra_9003_2001.html [Accessed 24 June 2018].

Congress of the Philippines. 2004. An act providing for a comprehensive water quality management and for other purposes. [online] The Lawphil Project 2004. Available at: www.lawphil.net/statutes/repacts/ra2004/ra_9275_2004.html [Accessed 24 June 2018].

DENR (Department of Environment and Natural Resources). 2002. Defining the organizational structure and major responsibilities of the Environmental Management Bureau as line bureau by virtue of Section 34 of the Philippine Clean Air Act of 1999. Manila, DoLE. Available at: http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache, http://www.mgb.gov.ph/images/stories/DAO_2002-17.pdf[Accessed 24 June 2018].

DoLE. 2017. Implementing rules and regulations of Republic Act No. 10771. [online] Manila, DoLE. Available at: www.dole.gov.ph/files/DO%20180-17%20Implementing%20Rules%20and%20Regulations%20of%20Republic%20Act%20No_%2010771.pdf [Accessed 24 June 2018].

ECOP (Employers Confederation of the Philippines), ILO (International Labour Organization). 2012. Synthesis of survey and focus group discussions on green jobs in Asia. Bangkok, ILO Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific. Available at: http://apgreenjobs.ilo.org/resources/meeting-resources/green-jobs-in-asia-regional-conference-flyer/conference-documents/green-jobs-projects-background-documents/green-jobs-in-asia-gja-project/philippines/synthesis-of-survey-and-focus-discussion-groups-on-green-jobs-ecop/at_download/file [Accessed 24 June 2018].

Ferriols, D. 2001. Philippine resins embarks on P1.7-B expansion. The Philippine Star. Available at: www.philstar.com/business/97031/philippine-resins-embarks-p17-b-expansion [Accessed 24 June 2018].

Ilagan, L., De Jesus, E. and Zarate, I. 2015. House Bill No. 5578. House of Representatives, Republic of the Philippines, p. 2. Available at: http://studylib.net/doc/8099303/1-republic-of-the-philippines-house-of [Accessed 24 June 2018].

ILO. 2012. Promoting decent work through integrating employment in industrial policies and sectoral strategies: Korea/ILO partnership program. Bangkok, ILO Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific. Available at: www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---asia/---ro-bangkok/---ilo-manila/documents/publication/wcms_179914.pdf [Accessed 24 June 2018].

ILO. 2017. Pilot application of policy guidelines on just transition towards environmentally sustainable economies and societies for all in the Philippines. Bangkok, ILO Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific. Available at: www.ilo.org/manila/projects/WCMS_522318/lang--en/index.htm [Accessed 24 June 2018].

International Monetary Fund. 2019. World Economic Outlook Database. [online] Available at: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/SPROLLs/world-economic-outlook-databases#sort=%40imfdate%20descending [Accessed 3 September 2019].

Montano, I. 2016. WHO: 6 million Asians die annually due to air pollution. CNN Philippines, 1 March 2016. Available at: http://cnnphilippines.com/news/2016/03/01/who-asians-air-pollution.html [Accessed 24 June 2018].

NEDA (National Economic and Development Authority). 2014. Philippine development plan 2011–2016: midterm update with revalidated results matrices. Available at: http://extwprlegs1.fao.org/docs/pdf/phi140998.pdf [Accessed 24 June 2018].

OECD. n.d. Greener skills and jobs. Highlights [PDF] Available at: www.oecd.org/cfe/leed/Greener%20skills_Highlights%20WEB.pdf [Accessed 24 June 2018].

Palaña, A. V. 2014. Stronger auto industry to save PH $17B in 5 yrs. The Manila Times. Available at: www.manilatimes.net/stronger-auto-industry-save-ph-17b-5-yrs/135069/ [Accessed 24 June 2018].

Pavlova, M. 2016. Regional overview: what is the government’s role in greening TVET? TVET perspective: major drivers behind skills and occupational changes. TVET@Asia, p. 6. Available at: www.tvet-online.asia/issue/6/pavlova [Accessed 24 June 2018].

PSA (Philippine Statistics Authority). 2010. 2010 annual survey of the Philippine business and industry, economy-wide. [online] Quezon City, PSA. Available at: http://psa.gov.ph/content/2010-annual-survey-philippine-business-and-industry-economy-wide-all-establishments-final [Accessed 24 June 2018].

PSA. 2012. 2012 census of Philippine business and industry – accommodation and food service activities for establishments with total employment of 20 and over: preliminary results. Census of Philippine Business and Industry. Quezon City, PSA. Available at: http://psa.gov.ph/content/2012-census-philippine-business-and-industry-accommodation-and-food-service-activities [Accessed 24 June 2018].

PSA. 2014. 2014 annual survey of the Philippine business and industry on water supply and sewerage waste management. Quezon City, PSA. Available at: https://psa.gov.ph/content/2014-annual-survey-philippine-business-and-industry-water-supply-sewerage-waste-management [Accessed 24 June 2018].

Silva, V. A. V. 2016. MSMEs urged: Go green. Cebu Daily News. http://cebudailynews.inquirer.net/109872/msmes-urged-go-green [Accessed 24 June 2018].

Stewards, E. 2000. The e-waste crisis. Introduction. Available at: http://e-stewards.org/the-e-waste-crisis/ [Accessed 24 June 2018].

TESDA (Technical Education and Skills Development Authority). 2017. National technical education and skills development plan (2011–2016). Manila, TESDA. Available at: www.tesda.gov.ph/Downloadables/NTESDP%20Text%20March%2017.doc [Accessed 24 June 2018].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Talavera, E. (2022). Case Study: Philippines. Recognising Green Skills for Environmental and Sustainable Development in Four Selected Industries. In: Pavlova, M., Singh, M. (eds) Recognizing Green Skills Through Non-formal Learning. Education for Sustainability, vol 5. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-2072-1_11

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-2072-1_11

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-19-2071-4

Online ISBN: 978-981-19-2072-1

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)