Abstract

This chapter develops the argument for twin propositions: (a) that the crisis in Indian agriculture cannot be resolved without a paradigm shift in water management and governance, and (b) that India’s water crisis requires a paradigm shift in agriculture. If three water-intensive crops use up 80% of agricultural water, the basic water needs of the country, for drinking water or protective irrigation, cannot be met. The paper sets out how this paradigm shift can be effected between 2020 to 2030—by shifting cropping patterns towards crops suited to each agroecological region, moving from monoculture to poly-cultural crop biodiversity, widespread adoption of water-saving seeds and technologies, a decisive move towards natural farming and greater emphasis on soil structure and green water. At the same time, we advocate protection of India’s catchment areas, a shift towards participatory approaches to water management, while building trans-disciplinarity and overcoming hydro-schizophrenia in water governance.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Green Revolution: Context and Achievements

Recent revisionist scholarshipFootnote 1 on the Green Revolution has conclusively established that the assumption of a stagnant food sector in the first two decades after independence is a myth (Balakrishnan, 2007). It also shows that neo-Malthusian fears of starvation in the Indian context were, indeed, exaggerated.Footnote 2 At the same time, there is also no denying that the Indian political leadership was deeply troubled by excessive dependence on wheat shipments under the PL-480 Food Aid Programme of the United States of America.Footnote 3 We cannot overlook the fact that 90% of the food that the government distributed through the public distribution system (PDS) between 1956 and 1960 came from imports and remained as high as 75% even during the period from 1961 to 1965. In 1965–66, the United States of America shipped 10 million tonnes of wheat to India (Tomlinson, 2013). At that point, India had less than half the food needed to provide a basic subsidised ration to the poorest 25% of the population (Krishna, 1972). Hence, there was a nationalist impulse that propelled the Green Revolution and it cannot be seen as merely a conspiracy of imperialist capital, although it is certainly the case that corporations supplying key inputs to Green Revolution agriculture were major beneficiaries of this radical policy shift.Footnote 4

What also needs to be acknowledged is that following the Green Revolution, India achieved self-sufficiency in food like never before. The buffer stock, which was hardly 3 million tonnes in the early 1970s, had already reached 60 million tonnes in 2012–13 (Table 1), and peaked at almost 100 million tonnes in July 2020 (Dreze, 2021). The single most important fact worth noting here is that in the early 1970s itself, the net sown area had almost reached 140 million hectares and this figure has remained more or less unchanged over the past five decades. During the same period, the gross cropped area has risen steadily with the cropping intensity growing from 119 to 140% (Table 2).

It can then be argued, somewhat more debatably, that without the intensification that occurred under the Green Revolution, the degradation of common lands and forests could have advanced at an even more rapid rate than it has done during this period.Footnote 5

2 Constituent Elements of the Green Revolution Paradigm

Subramanian (2015) is right in arguing that these achievements were not the result merely of moving to high-yielding dwarf varieties of seeds. Indeed, it is extremely important to recognise that the Green Revolution was a package deal, a combination of radical changes in the political economy of Indian agriculture, with several path-breaking interventions. These included the following:

-

Higher-yielding seeds and concomitant use of chemical fertilisers and pesticides: The consumption of fertilisers rose dramatically from 2 million tonnes in 1970–71 to more than 27 million tonnes in 2018–19 (Table 3). Similarly, synthetic pesticide consumption has grown sharply over the past decade (Table 4). Just six states (Maharashtra, Uttar Pradesh, Punjab, Telangana, Haryana and West Bengal) together accounted for about 70% of total chemical pesticide consumption in the country in 2019–20.

Table 3 Fertiliser consumption in India, 1950–2019 Table 4 Synthetic pesticide consumption in India, 2001–2020

-

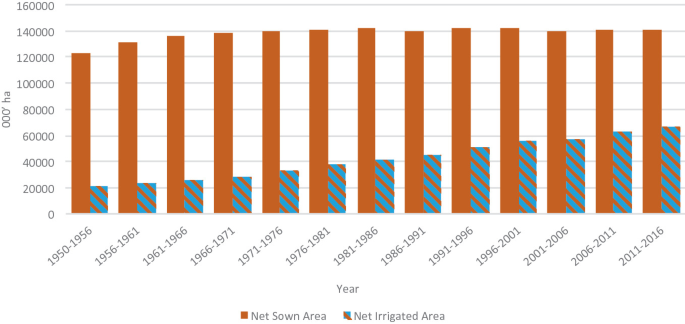

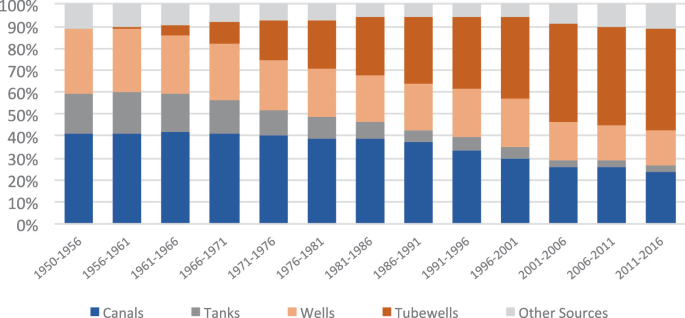

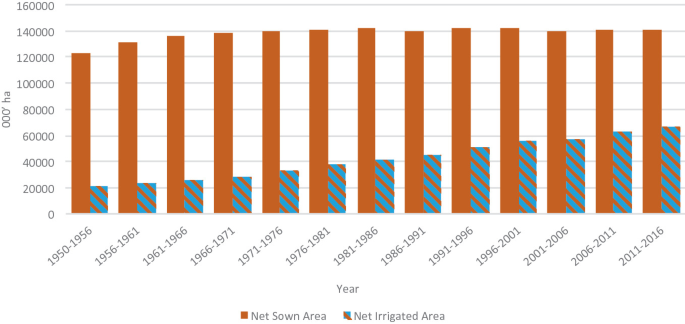

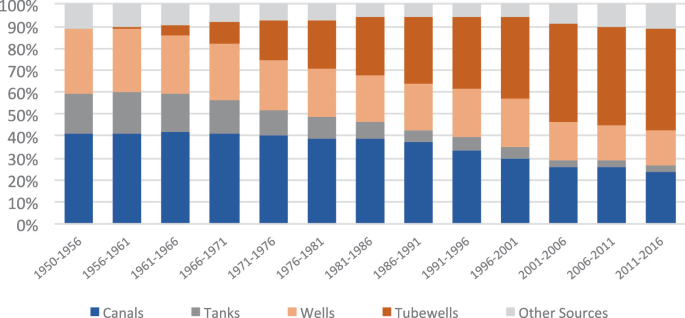

Breakthrough in irrigation: Following the Green Revolution there was a sea-change in the extent of irrigation, as well as in the way India irrigated her fields. Irrigated area more than doubled, both in absolute terms and as a percentage of net sown area (Fig. 1). Over time, groundwater, especially that provided by deep tubewells, has become the single largest source of irrigation (Fig. 2). This form of irrigation allows farmers greater control over water—as and when, and in the volumes that the crops require it. Over the last four decades, around 84% of total addition to the net irrigated area has come from groundwater. At 250 billion cubic metres (BCM), India draws more groundwater every year than any other country in the world. India’s annual consumption is more than that of China and the United States of America (the second and third largest groundwater-using countries) put together (Vijayshankar et al., 2011).

Fig. 1

Source DAC (2020). https://eands.dacnet.nic.in

All-India net sown and net irrigated area, 1950–2016.

Fig. 2

Source DAC (2020). https://eands.dacnet.nic.in

All-India percentage of irrigation from different sources, 1950–2016. Note “Other Sources” largely include groundwater sources, such as dug-cum-borewells. Hence, groundwater could well be said to account for nearly 70% of irrigation today.

-

Easier availability of credit: The access to seeds, fertilisers, pesticides and new irrigation technology was made possible by the easier availability of credit. The nationalisation of 14 banks in 1969 was a landmark step in the direction of improving access to reasonably priced credit in rural India. Recent arguments in favour of re-privatisation overlook the fact that the National Credit Council found that before nationalisation not even 1% of India’s villages were served by commercial banks. Furthermore, in 1971, the share of banks in rural credit was no more than 2.4%, with most of these loans being made to plantations, not farmers. It is the easier availability of credit that fuelled the investments that drove India’s Green Revolution (Shah et al., 2007).Footnote 6

-

Role of the agricultural extension system: Since the Green Revolution meant a completely new way of doing farming, a critical role was played by the state-supported agricultural extension system. Today, it may be quite difficult to imagine what a humongous task this was, covering hundreds of thousands of farmers. Of course, the paradigm of agricultural extension during the Green Revolution was what may be described as ‘top-down, persuasive and paternalistic technology transfer’, which provided specific recommendations to farmers about the practices they should adopt. If an alternative is to be found to the Green Revolution today, great effort will be needed to re-energise and re-orient this extension system, which today finds itself in a state of almost total collapse. It will also be necessary to move towards a much more ‘farmer-to-farmer participatory extension system’.

-

A stable market: The setting up of the Food Corporation of India (FCI) in 1965 and the ensuing—and expanding—procurement operations at minimum support prices (MSPs) ensured a stable market for the farmers.Footnote 7 Without this state intervention, left to the vagaries of the free market, the Green Revolution would not have taken off, as the expanded output could have created problems for the farmers, due to a fall in price at times of bumper harvest.Footnote 8

3 Wheels Come Off the Green Revolution

While it is undeniable that the Green Revolution paradigm represents a powerful break from the past that provided India with comfortable food security,Footnote 9 it is also true that over the decades that followed, it sowed the seeds of its own destruction, leading to a grave farming crisis in India today. More than 300,000 farmers have committed suicide in the last 30 years, a phenomenon completely unprecedented in Indian history.Footnote 10 There is growing evidence of steady decline in water tables and water quality. At least 60% of India’s districts are either facing a problem of over-exploitation or severe contamination of groundwater (Vijayshankar et al., 2011). There is evidence of fluoride, arsenic, mercury and even uranium and manganese in groundwater in some areas. The increasing levels of nitrates and pesticide pollutants in groundwater have serious health implications. The major health issues resulting from the intake of nitrates are methemoglobinemia and cancer (WHO, 2011). The major health hazards of pesticide intake through food and water include cancers, tumours, skin diseases, cellular and DNA damage, suppression of the immune system and other intergenerational effects (Margni et al., 2002).Footnote 11 Repetto and Baliga (1996) provide experimental and epidemiological evidence that many pesticides widely used around the world are immune-suppressive. Nicolopoulou-Stamati et al. (2016) provide evidence of pesticide-induced temporary or permanent alterations in the immune systems and Corsini et al. (2008) show how such immune alteration could lead to several diseases. Agricultural workers spraying pesticides are a particularly vulnerable group, especially in India where they are rarely provided protective gear. A study of farm workers in Punjab found significantly higher frequency of chromosomal aberrations in peripheral blood lymphocytes of workers exposed to pesticides, compared to those not exposed (Ahluwalia & Kaur, 2020). A study of 659 pesticides, which examined their acute and chronic risks to human health and environmental risks, concludes that

evidence demonstrates the negative health and environmental effects of pesticides, and there is widespread understanding that intensive pesticide application can increase the vulnerability of agricultural systems to pest outbreaks and lock in continued reliance on their use. (Jepson et al., 2020)

It is also clear that the yield response to the application of increasingly more expensive chemical inputs is falling. Indoria et al. (2018) show that the average crop response to fertiliser use has fallen from around 25 kg grain/kg of nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium (NPK) fertiliser during the 1960s to a mere 6 kg grain/kg NPK by 2010 (Fig. 3). This has meant higher costs of cultivation, without a corresponding rise in output, even as this intensified application of inputs compels farmers to draw more and more water from below the ground.

Source Indoria et al. (2018, Fig. 2)

Relationship between fertiliser consumption and crop productivity.

Moreover, despite overflowing granaries, the 2021 Global Hunger Index Report ranked India 101 out of 116 countries.Footnote 12 FAO et al. (2020) estimate that more than 189 million people remained malnourished in India during 2017–19, which is more than a quarter of the total such people in the world.Footnote 13 In 2019, India had 28% (40.3 million) of the world’s stunted children (low height-for-age) and 43% (20.1 million) of the world’s wasted children (low weight-for-height) under five years of age.Footnote 14

Paradoxically, at the same time, diabetics have increased in every Indian state between 1990 and 2016, even among the poor, rising from 26 million in 1990 to 65 million in 2016. This number is projected to double by 2030 (Shah, 2019).

4 The Paradigm Shift Required in Agriculture

It is important to understand precisely why this multi-fold unravelling was inherent in the very architecture of the Green Revolution and what can be done to institute a paradigm shift in farming in India.

4.1 Not Quite a Green Revolution: Towards Crop Diversification Reflecting Agroecology of Diverse Regions

It is now widely recognised that the Green Revolution was simply a wheat-rice revolution.Footnote 15

As can be seen from Tables 5 and 6, over the past 50 years, the share of nutri-cereals in cropped area has gone down dramatically in all parts of India. Even in absolute terms the acreage under these cereals has almost halved between 1962–65 and 2012–14. The share of pulses has also drastically come down in the states of Assam, Bihar, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, erstwhile Jammu and Kashmir, Jharkhand, Odisha, Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand and West Bengal. The share of oilseeds appears to have risen, but that is mainly on account of the rise in acreage under soya.Footnote 16 Figure 4 shows that the share of soyabean in oilseeds acreage rose from less than 1% in the early 1970s to over 40% in 2016–17, even as the share of the other eight oilseeds has stagnated. Other than soyabean, the only other crops showing a rise in acreage during the period of the Green Revolution are wheat, rice and sugarcane.

Source DAC (2018). Agricultural Statistics at a Glance

Share of soyabean in total area under oilseeds.

The rise in the acreage of wheat and rice is a direct consequence of the procurement and price support offered by the state. In the case of sugarcane and soyabean, the rise in acreage is due to the purchase by sugar mills and soya factories. But the main story of the Green Revolution is the story of rice and wheat, which remain the overwhelming majority of crops procured by the government even today, even after a few states have taken tentative steps towards diversification of their procurement basket to include nutri-cereals and pulses (Table 7). What is worse, public procurement covers a very low proportion of India’s regions and farmers (Khera et al., 2020).

This also reflects the fact that the primary target of procurement is the consumer, not so much the farmer. Thus, procurement gets limited to what is needed to meet the requirements of consumers. This showed up in the way imports of pulses were ramped up during 2016–18, even though it had been decided to try and expand procurement of pulses. The latter suffered as a result and pulse growers were the losers. Thus, the pathway for reforms becomes very clear: we need to greatly expand the basket of public procurement to include more crops, more regions and more farmers.Footnote 17 By doing so we can make a huge dent in solving India’s water problem, while at the same time tackling farmer distress and India’s nutritional crisis.

A recent study supported by the National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD) and the Indian Council for Research in International Economic Relations (ICRIER) estimated that about 78% of India’s water is consumed in agriculture (Sharma et al., 2018). FAO’s AQUASTAT database puts this figure closer to 90% (FAO, 2019). The NABARD-ICRIER study identified three “water guzzler” crops—rice, wheat and sugarcane—which occupy about 41% of the gross cropped area and consume more than 80% of irrigation water. Shah (2019) suggests that sugarcane, which occupies just 4% of cropped area, uses up 65% of irrigation water in Maharashtra. In Karnataka, rice and sugarcane, which cover 20% of cropped area, consume as much as 70% of irrigation water (Karnataka Knowledge Commission, 2019). This has meant grave inequity in the distribution of irrigation water across crops and farmers, and also a terrible mismatch between existing water endowments and the water demanded by these water-guzzling crops. The main reason why farmers grow such crops even in areas of patent water shortage is the structure of incentives, as they find that these crops have steady markets. Even a small reduction in the area under these crops, in a region-specific manner and in a way that does not endanger food security, would go a long way in addressing India’s water problem.

Thus, the first element of the paradigm shift required in Indian agriculture is to change this distorted structure of incentives. The most important step in this direction is for the government to diversify its crop procurement operations in a very carefully calibrated, location-specific manner, to align with local agroecologies. The best way of doing this is to start procurement of crops that match the agroecology of each region.

India’s cropping pattern before the Green Revolution included a much higher share of millets, pulses and oilseeds. These agroecologically appropriate crops must urgently find a place in public procurement operations. As this picks up pace, farmers will also gradually diversify their cropping patterns in alignment with this new structure of incentives. The largest outlet for the millets, oilseeds and pulses procured in this manner—in line with the POSHAN AbhiyaanFootnote 18 launched by the Government of India—would be the supplementary nutrition and meals provided under the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) and the Pradhan Mantri Poshan Shakti Nirman Yojana (PM POSHAN Scheme),Footnote 19 as also the grains provided through the PDS.

A few state governments are also slowly moving forward in this direction. The Odisha Millets Mission (OMM) initiated in 2017–18 works on four verticals—production, processing, marketing and consumption, through a unique institutional architecture of partnerships with academia and civil society. As of 2020–21, the programme, aimed at encouraging 100,000 farmers to cultivate millets, had spread across 76 blocks in 14 districts. The mandia ladoos (finger millet sweet) prepared by women self-help groups (SHGs) and introduced by the Government of Odisha under the ICDS have proved extremely popular among the pre-school children (Jena & Mishra, 2021). Reports from the ground in 2020 describe the overwhelming enthusiasm, especially among tribal farmers, who were typically hitherto excluded, and how they undertook arduous journeys to reach government procurement centres (Dinesh Balam, personal communication).

A similar noteworthy example is that of the tribal-dominated Dindori district in Madhya Pradesh, a malnutrition hotspot in recent decades. Here a state government-civil society partnership has led to a revival in the cultivation of kodo (Dutch millet) and kutki (little millet), which are renowned for their anti-diabetic and nutritional properties. The Government of Madhya Pradesh’s Tejaswini Rural Women's Empowerment programme helped women SHG federations develop a business plan for establishing a supply-chain for kodo bars and barfis (fudge), which were included in the ICDS supplementary nutrition programme. The products were clinically tested for their nutrient content at laboratories certified by the National Accreditation Board for Testing and Calibration Laboratories (NABL), to ensure appropriate standards of taste and quality (Mathur & Ranjan, 2021). These are the kinds of reforms and outreach all states need to pursue, with support from the Centre.

Done at scale, this would enable a steady demand for these nutritious crops and help sustain a shift in cropping patterns, which would provide a corrective to the currently highly skewed distribution of irrigation to only a few crops and farmers. It would also be a significant contribution to improved nutrition, especially for children, and a powerful weapon in the battle against the twinned curse of malnutrition and diabetes.

It is quite evident that a major contributor to this “syndemic” is the displacement of whole foods in the average Indian diet by energy-dense and nutrient-poor, ultra-processed food products.Footnote 20 Recent medical research has found that some millets contain significant anti-diabetic properties. According to the Indian Council of Medical Research, foxtail millet has 81% more protein than rice. Millets have higher fibre and iron content, and a low glycemic index. Millets also are climate-resilient crops suited for the drylands of India. If children were to eat these nutri-cereals—which provide a higher content of dietary fibre, vitamins, minerals, protein and antioxidants and a significantly lower glycemic index—India would be better placed to solve the problems of malnutrition and obesity.

To clarify, this is not a proposal for open-ended public procurement. That would be neither feasible nor desirable. The argument is for diversification of the procurement basket to include crops suited to local agroecologies. A useful benchmark could be 25% of the actual production of the commodity for that particular year/season (to be expanded up to 40%, if the commodity is part of the PDS), as proposed under the 2018 PM-AASHAFootnote 21 scheme. Without such an initiative, the announcement of MSPs for 23 crops every year is reduced to a token ritual, with little benefit to most farmers.

If such a switch in cropping patterns, to reflect the agroecological diversity of India, were to be effected, what volume of water would India save by the year 2030? We have made an attempt to quantify the water that could be saved each year in 11 major agricultural states: Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Gujarat, Haryana, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Punjab, Rajasthan, Telangana and Tamil Nadu.Footnote 22 These states together accounted for about 66% of the total irrigated area of the country in 2015–16. We quantify the baseline water used in the production of crops using the average (mean) yields and areas for each crop in each state in the most recent ten-year period for which data are available. We compare the baseline water use to two exploratory scenarios of crop replacements:

-

Scenario 1 (small change): Replacement of high water-demanding crops with low water-using ones to the extent of 10–25% of the crop area in the kharif season and 25% in the rabi season; and

-

Scenario 2 (higher change): Replacement of high water-demanding crops with low water-using ones to the extent of 25–50% of the crop area in the kharif season and 50% in the rabi season.

Rice is the major irrigated crop in the southern states of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Telangana and Tamil Nadu, while wheat is the major irrigated crop in Bihar, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan. Both rice and wheat are heavily irrigated in Punjab and Haryana. We explore possible crop switches in both kharif and rabi seasons. In each state, we have taken one high water footprint crop in each season and estimated water saving by switching the area under this crop to two lower water footprint crops. Table 8 gives the list of states and seasons analysed.

First, we quantify baseline crop production based on recent yield and area data.Footnote 23 Our purpose is to build different scenarios to demonstrate the potential of water savings through crop replacements. For estimating the irrigation water use in these crop replacement scenarios, we have calculated blue water footprints, which represent the volume of water consumed during crop production in m3 per tonne. Season and state-specific water footprints for cereal crops were drawn from Kayatz et al. (2019) and for other crops from Mekonnen and Hoekstra (2011).Footnote 24 In this method, the total evapo-transpiration (ET) requirement of the crops is estimated using FAO’s CROPWAT model. National and state specific ET for each of the crops studied is generated, which is modified by the crop factor (k) to get estimated consumptive use of water or total water footprint (TWF) by each crop in each state. The proportion of the green water footprint (GWF) is estimated by modelling effective rainfall during the season. The difference between TWF and GWF is attributed to the irrigation component or the blue water footprint (BWF) of crops.Footnote 25 The BWF is multiplied by crop production, to get estimated blue water use by crops in each state in each season.Footnote 26

To estimate the potential for annual water savings, we propose crop switches in both kharif and rabi crops in different states, through the scenarios in Table 8.Footnote 27

In these 11 states, we take the area under three most water-intensive crops, namely rice, wheat and sugarcane, and re-distribute the area to the replacement crops,Footnote 28 which are largely pulses and nutri-cereals. The choice of the replacement crops is governed by an analysis of the cropping pattern of the concerned state in the period before the monoculture of the Green Revolution took firm roots there. Thus, these are crops suited to the agroecology of each region and, therefore, their revival has a solid basis in both agricultural science and farmer experience. The water savings were calculated based on the change in irrigation water required for each state in each season. Irrigation water savings are given as the difference between the water-use at baseline as compared to the crop replacement scenarios. In order to make suitable and realistic proposals for crop replacements, we consider several factors:

-

Seasons: Crop production is strongly determined by seasons, which need to be taken into account while proposing replacements. For example, since most of the nutri-cereals are grown in the kharif season, we cannot propose a replacement of wheat (a predominantly winter crop) with nutri-cereals like jowar. Crop growing seasons for rice in Tamil Nadu are such that the proposals for replacement have to consider if the sowing and harvesting time of the replacement crops match those of rice. Similarly, for replacement of an annual crop like sugarcane in Maharashtra, we have identified a crop sequence covering both the kharif and rabi seasons, so that the replacement of one crop is with a group of two or more crops.

-

Source of irrigation and extent of control over water: Crops grown in command areas of large dams are largely irrigated by the field-flooding method. It is, therefore, difficult to replace rice grown in the canal commands and floodplains of rivers like the Godavari and Krishna in Andhra Pradesh with any other crop. However, in the non-command areas of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, mainly the undulating and upland regions, it is possible to replace rice because the major source of irrigation here is groundwater. The situation in Punjab and Haryana is similar, since groundwater accessed through tubewells is the major source of irrigation.

-

Soil conditions and agronomy: Once certain crops like rice are continuously grown in an area, the soil conditions change considerably so that any crop replacement may become difficult. This particularly applies to the low-lying regions of West Bengal, Odisha and Chhattisgarh. Similarly, when inter-cropping is practised, there are certain crop combinations involved. So, when we propose replacement of one crop (such as soyabean in Madhya Pradesh), we need to also propose replacement of other crops in the crop mix when the inter-crop does not match with the replacement crop.

Based on these considerations and limiting factors, Table 9 brings together the state-specific and season-specific crop replacements proposed.

Table 10 provides a comparison of the total blue water saved (cubic kilometres or billion cubic metres) in 11 states after crop replacements in Scenarios I and II, as compared to the irrigation water required to produce the water-intensive crops in the baseline scenario.

Given that water-intensive crops currently occupy over 30% of the gross irrigated area in these states, the amount of water saved annually is considerable. This water could be diverted to critical and supplementary irrigation for millions of small and marginal farmers, while also reducing the pressure on rural drinking water sources.

It can be argued that these crop replacements will result in some reduction in total output because of differentials in yields across crops.Footnote 29 However, it must be borne in mind that the rapidly deteriorating water situation increasingly poses a very serious constraint to maintaining the productivity levels of water-intensive crops, especially in states like Punjab and Haryana. An extremely important recent study has concluded that

given current depletion trends, cropping intensity may decrease by 20% nationwide and by 68% in groundwater-depleted regions. Even if surface irrigation delivery is increased as a supply-side adaptation strategy, cropping intensity will decrease, become more vulnerable to inter-annual rainfall variability, and become more spatially uneven. We find that groundwater and canal irrigation are not substitutable and that additional adaptation strategies will be necessary to maintain current levels of production in the face of groundwater depletion. (Jain et al., 2021)

Hence, it would be fallacious to assume that output levels of water-intensive crops can be sustained indefinitely in heavily groundwater dependent states like Punjab and Haryana. At the same time, our proposal is for aligning cropping patterns with regional agroecology and that includes raising the share of Eastern India in the national output of water-intensive crops like rice. Ironically, even though this region has abundant water resources, it depends on groundwater scarce regions for its supply of food grains. It has been correctly pointed out that “Eastern states which are safe in their groundwater reserves and net importers, also have the highest yield gaps and therefore the greatest unmet potential to increase production” (Harris et al., 2020, p. 9). Raising the share of rice procured from Eastern India would greatly help a move in this direction, as would tweaking electricity tariffs there (Sidhu et al., 2020). We must also clearly recognise that food stocks over the last decade have greatly exceeded the ‘buffer norm’, which is around 31 million tonnes for wheat and rice. Indeed, even after all the additional drawals following the COVID-19 pandemic, the Central pool still had 63 million tonnes in stock in October 2020 (Husain, 2020).Footnote 30

Moreover, the nutritional content of the crop mix we are proposing is definitely superior. Increasing consumption of nutri-cereals over rice and wheat could reduce iron-deficiency anaemia, while the increased consumption of pulses could reduce protein-energy malnutrition (DeFries et al., 2018). The impact on farmers’ incomes is also likely to be positive because of lower input requirements and costs of production associated with our crop-mix. What would help significantly is more emphasis on research and development (R&D) in the replacement crops, stronger farmer extension support for them, as also expanded procurement and higher price support in order to create the right macro-economic environment for crop replacement.Footnote 31

4.2 Monoculture Impairs Resilience: Return to Polycultural Biodiversity

Farming faces twin uncertainties, stemming from the market and the weather. For such a risky enterprise to adopt monoculture is patently suicidal.Footnote 32 But that is what the Green Revolution has moved Indian farming towards: more and more land under one crop at a time and year-on-year production of the same crop on the same land.

This reduces the resilience of farm systems to weather and market risks, with even more grave consequences in this era of rapid climate change and unpredictable patterns of rainfall. In 2018 and 2019, India had at least one extreme weather event every month. In different regions, these included shortages and excesses of rainfall, higher and lower temperatures etc., many of which exceeded the bounds of normal expectation. A recent report of the Ministry of Earth Sciences (MoES), Government of India (Krishnan et al., 2019) finds that June to September rainfall over India has declined by around 6% from 1951 to 2015, with notable decreases over the Indo-Gangetic plains and the Western Ghats. During the same period, the frequency of daily precipitation extremes, with rainfall intensities exceeding 150 mm per day, increased by about 75% over central India. Dry spells were 27% more frequent during 1981–2011 compared to 1951–1980. Both the frequency and spatial extent of droughts have increased significantly between 1951 and 2016. Climate models project an increase in the frequency, intensity and area under drought conditions in India by the end of the twenty-first century.

The persistence of monoculture makes India even more vulnerable to disruptions from climate change and extreme weather events, for it has by now been conclusively established that

crops grown under ‘modern monoculture systems’ are particularly vulnerable to climate change as well as biotic stresses, a condition that constitutes a major threat to food security … what is needed is an agro-ecological transformation of monocultures by favoring field diversity and landscape heterogeneity, to increase the productivity, sustainability, and resilience of agricultural production. … Observations of agricultural performance after extreme climatic events in the last two decades have revealed that resiliency to climate disasters is closely linked to farms with increased levels of biodiversity. (Altieri et al., 2015)

The vast monocultures that dominate 80% of the 1.5 billion hectares of arable land are one of the largest causes of global environmental changes, leading to soil degradation, deforestation, depletion of freshwater resources and chemical contamination. (Altieri & Nicholls, 2020)

It has also been shown that plants grown in genetically homogenous monocultures lack the necessary ecological defence mechanisms to withstand the impact of pest outbreaks. Francis (1986) summarises the vast body of literature documenting lower insect pest incidence and the slowing down of the rate of disease development in diverse cropping systems compared to the corresponding monocultures. In his classic work on inter-cropping, Vandermeer (1989) provides innumerable instances of how inter-cropping enables farmers to minimise risk by raising various crops simultaneously. Natarajan and Willey (1986) show how polycultures (intercrops of sorghum and peanut, millet and peanut and sorghum and millet) had greater yield stability and showed lower declines in productivity during a drought than monocultures.

Most recently, the largest ever attempt in this direction (Tamburini et al., 2020) has included a review of 98 meta-analyses and a second-order meta-analysis based on 5160 original studies comprising 41,946 comparisons between diversified and simplified practices. They conclude:

Enhancing biodiversity in cropping systems is suggested to promote ecosystem services, thereby reducing dependency on agronomic inputs while maintaining high crop yields. Overall, diversification enhances biodiversity, pollination, pest control, nutrient cycling, soil fertility, and water regulation without compromising crop yields. (Tamburini et al., 2020)

A recent report of the FAO’s Commission on Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture also brings out the key role of biodiversity in sustaining crop production:

The world is becoming less biodiverse and there is good evidence that biodiversity losses at genetic, species and ecosystem levels reduce ecosystem functions that directly or indirectly affect food production, through effects such as the lower cycling of biologically essential resources, reductions in compensatory dynamics and lower niche occupation. (Dawson et al., 2019)

Moreover, as a recent study of agro-biodiversity in India argues, “when we lose agricultural biodiversity, we also lose the option to make our diets healthier and our food systems more resilient and sustainable” (Thomson Jacob et al., 2020).Footnote 33 It is thus clear how a move away from monoculture towards more diverse cropping patterns would increase resilience against climate and market risks, while also reducing water consumption, without compromising productivity.

4.3 Rejecting the Originative Flaw (Soil as an Input–Output Machine)

The fundamental question that needs to be raised about the Green Revolution is its overall strategy, its conception of the agricultural production system in general, and of soils in particular. The overarching strategy was one of “betting on the strong”, which meant focusing investment and support on farmers, regions and crops that were seen as most likely to lead to an increase in output (Tomlinson, 2013). It was a “commodity-centric” vision, where the idea was to deploy such seeds as would maximise output per unit area, given the right doses of fertilisers and pesticides. The amount of chemical nutrients applied demanded correspondingly larger inputs of water, which, in turn, made the resultant ecosystem extremely favourable to the profusion of pests, which threatened output unless pesticides were utilised to kill them.

This is a perspective that exclusively focuses on productivity (output/area) of a given crop by specifically targeting soil nutrients or pest outbreaks (Hecht, 1987). Such a view is atomistic, and assumes that “parts can be understood apart from the systems in which they are embedded and that systems are simply the sum of their parts” (Norgaard & Sikor, 1995). It is also mechanistic, in that relationships among parts are seen as fixed, changes as reversible and systems are presumed to move smoothly from one equilibrium to another. Such a view ignores the fact that often parts cannot be understood separately from their wholes and that the whole is different (greater or lesser) than the sum of its parts. It also overlooks the possibility that parts could evolve new characteristics or that completely new parts could arise (what is termed as ‘emergence’ in soil science literature).Footnote 34 As Lent (2017) argues:

Because of the way a living system continually regenerates itself, the parts that constitute it are in fact perpetually being changed. It is the organism’s dynamic patterns that maintain its coherence. … This new understanding of nature as a self-organized, self-regenerating system extends, like a fractal, from a single cell to the global system of life on Earth.

On the other hand, in the Green Revolution vision, the soil was seen essentially as a stockpile of minerals and salts, and crop production was constrained as per Liebig’s Law of the Minimum—by the nutrient least present in the soil. The solution was to enrich the soil with chemical fertilisers, where the soil was just a base with the physical attributes necessary to hold roots: “Crops and soil were brute physical matter, collections of molecules to be optimised by chemical recipes, rather than flowing, energy-charged wholes” (Mann, 2018).

Thus, the essential questions to be posed to a continued blind adherence to the Green Revolution approach, in the face of India’s growing farm and water crises, are:

-

1.

Is the soil an input–output machine, a passive reservoir of chemical nutrients, to be endlessly flogged to deliver, even as it shows clear signs of fatigue?

-

2.

Or is it a complex, interacting, living ecosystem to be cherished and maintained so that it can become a vibrant, circulatory network, which nourishes the plants and animals that feed it?

-

3.

Will a toxic, enervated ecosystem with very poor soil quality and structure, as also gravely fallen water tables, be able to continue to support the agricultural production system?

In the words of Rattan Lal, the Indian-American soil scientist, who is also the 2020 World Food Prize winner:

Soil is a living entity. It is full of life. The weight of living organisms in a healthy soil is about 5 ton per hectare. The activity and species diversity of soil biota are responsible for numerous essential ecosystem services. Soil organic matter content is an indicator of soil health, and should be about 2.5% to 3.0% by weight in the root zone (top 20 cm). But soil in Punjab, Haryana, Rajasthan, Delhi, Central India and Southern parts contains maybe 0.5% or maybe 0.2%.Footnote 35

According to FAO, generating 3 cm of top soil takes 1000 years, and, if current rates of degradation continue, all of the world’s top soil could be gone within 60 years.Footnote 36 Lal favours compensation for farmers through payments (around INR 1200 per acre per year) for soil protection, which he regards as a vital ecosystem service.

It is important to understand the key relationship between soil quality and water productivity and recognise that every land-use decision is also a water-use decision (Bossio et al., 2008). Lal (2012) explains how soil organic matter (SOM) affects the physical, chemical, biological and ecological qualities of the soil. In physical terms, higher SOM improves the water infiltration rate and the soil’s available water-holding capacity. Chemically, it has a bearing on the soil’s capacity to buffer against pH, as also its ion-exchange and cation-exchange capacities, nutrient storage and availability and nutrient-use efficiency. Biologically, SOM is a habitat and reservoir for the gene pool, for gaseous exchange between the soil and the atmosphere and for carbon sequestration. Ecologically, SOM is important in terms of elemental cycling, ecosystem carbon budget, filtering of pollutants and ecosystem productivity.Footnote 37

A recent overview of global food systems rightly points to the “paradox of productivity”:

as the efficiency of production has increased, the efficiency of the food system as a whole – in terms of delivering nutritious food, sustainably and with little waste – has declined. Yield growth and falling food prices have been accompanied by increasing food waste, a growing malnutrition burden and unsustainable environmental degradation. (Benton & Bailey, 2019)

Benton and Bailey urge policy-makers to move from the traditional preoccupation with Total Factor Productivity (TFP) towards Total System Productivity (TSP):

A food system with high TSP would be sufficiently productive (to meet human nutritional needs) whilst imposing few costs on the environment and society (so being sustainable), and highly efficient at all stages of the food chain so as to minimize waste. It would optimize total resource inputs (direct inputs and indirect inputs from natural capital and healthcare) relative to the outputs (food utilization). Maximizing TSP would maximize the number of people fed healthily and sustainably per unit input (direct and indirect). In other words, it would increase overall systemic efficiency. (ibid.)

In the light of this understanding, attempts are being made all over the world to foster an ecosystem approach, with higher sustainability and resilience, lower costs of production, as also economy in water use, along with higher moisture retention by the soil. Broadly, these alternatives to the Green Revolution paradigm come under the rubric of agroecology. In the latest quadrennial review of its Strategic Framework and Preparation of the Organization’s Medium-Term Plan, 2018–21, the FAO states:

High-input, resource-intensive farming systems, which have caused massive deforestation, water scarcities, soil depletion and high levels of greenhouse gas emissions, cannot deliver sustainable food and agricultural production. Needed are innovative systems that protect and enhance the natural resource base, while increasing productivity. Needed is a transformative process towards ‘holistic’ approaches, such as agroecology and conservation agriculture, which also build upon indigenous and traditional knowledge.

Hecht (1987) provides an excellent summary of the philosophy underlying agroecology:

At the heart of agro-ecology is the idea that a crop field is an ecosystem in which ecological processes found in other vegetation formations such as nutrient cycling, predator/prey interactions, competition, commensalism, and successional changes also occur. Agro-ecology focuses on ecological relations in the field, and its purpose is to illuminate the form, dynamics, and function of these relations (so that) … agro-ecosystems can be manipulated to produce better, with fewer negative environmental or social impacts, more sustainably, and with fewer external inputs.

A recent overview sums up key features of the approach embodied by agroecology:

Over the past five years, the theory and practice of agroecology have crystalized as an alternative paradigm and vision for food systems. Agroecology is an approach to agriculture and food systems that mimics nature, stresses the importance of local knowledge and participatory processes and prioritizes the agency and voice of food producers. As a traditional practice, its history stretches back millennia, whereas a more contemporary agroecology has been developed and articulated in scientific and social movement circles over the last century. Most recently, agroecology—practised by hundreds of millions of farmers around the globe—has become increasingly viewed as viable, necessary and possible as the limitations and destructiveness of ‘business as usual’ in agriculture have been laid bare. (Anderson et al., 2021)

In India, a large number of such alternatives to the Green Revolution paradigm have emerged over the past two decades. These include natural farming, non-pesticide managed agriculture, organic farming, conservation agriculture, low external input sustainable agriculture, etc. but they all share a common base of agroecological principles, rooted in the local context. Recently some state governments have given a big push to this movement. The biggest example is that of the Community Based Natural Farming programme of the Government of Andhra Pradesh (GoAP), which started in 2016.Footnote 38 Crop-cutting experiments by the State Agriculture Department claim higher average yields, reduced costs and higher net incomes for ‘natural’ farmers compared to ‘non-natural’ farmers, in all districts and for all crops. Encouraged by the results, the GoAP has now resolved to cover the entire cultivable area of 80 lakh hectares in the state by 2027 (Vijay Kumar, 2020). This would then become the largest challenge to the Green Revolution ever undertaken.

Support has also been forthcoming from the Government of India. At an event organised by the NITI Aayog on 29 May 2020, the Union Minister for Agriculture stated:

Natural farming is our indigenous system based on cow dung and urine, biomass, mulch and soil aeration […]. In the next five years, we intend to reach 20 lakh hectares in any form of organic farming, including natural farming, of which 12 lakh hectares are under Bharatiya Prakritik Krishi Paddhati Programme.Footnote 39

At the same event, the NITI Aayog Vice-Chairman stressed the need to take natural farming to scale:

In states like Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Gujarat, Himachal Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh this is being practised already quite widely. It has proven its benefit on the ground. Now is the time that we should scale it and make it reach 16 crore farmers from the existing 30 lakhs. The whole world is trying to move away from chemical farming. Now is the time to make Indian farmers aware of its potential.Footnote 40

These agroecological alternatives embody a paradigm shift in farming and have a crucial role to play in redressing both farmer distress and India’s worsening water crisis.

4.4 Water Saving Seeds and Technologies

Through careful micro-level trials and experimentation by their field centres, the Indian Agricultural Research Institute (IARI) and state agricultural universities have developed several crop varieties, which require less water than conventional Green Revolution seeds. For example, the low-irrigation wheat varieties Amar (HW 2004), Amrita (HI 1500), Harshita (HI 15231), Malav Kirti (HI 8627) and Malav Ratna (HD 4672), developed at the IARI Wheat Centre in Indore, give fairly good yields at a much lower level of water consumption (Gupta et al., 2018). These varieties are also prescribed by the ICAR-NICRA (Indian Council for Agricultural Research-National Innovations on Climate Resilient Agriculture) project, through their district-level drought adaptation plans.Footnote 41 Adoption of these varieties by farmers would need training and facilitation by Krishi Vigyan KendrasFootnote 42 (KVKs) so that they are able to understand the new agronomic practices that these varieties would involve. Their large-scale adoption could go a long way in reducing the water footprint of water-intensive crops.Footnote 43

Adoption of water saving practices can also achieve the same result (as summarised in Table 11). System of Rice Intensification is a combination of practices which, together, reduce heavy input use in rice. Conservation agriculture and tillage refers to methods where the soil profile is not disturbed by tilling. Drip irrigation takes water application closer to the root systems of plants (Narayanamoorthy, 2004). Direct Seeding of Rice enables sowing of rice without nurseries or transplanting. Uneven soil surface affects the germination of crops, reduces the possibility of spreading water homogenously and reduces soil moisture. Therefore, land levelling within farmsFootnote 44 is a precursor to good agronomic, soil and crop management practices.

4.5 Reversing the Neglect of Rainfed Areas: Focus on Green Water and Protective Irrigation

One of the most deleterious consequences of the Green Revolution has been the neglect of India’s rainfed areas, which currently account for 54% of the sown area.Footnote 45 The key to improved productivity of rainfed farming is a focus on soil moisture and protective irrigation. Protective irrigation seeks to meet moisture deficits in the root zone, which are the result of long dry spells. Rainfed crops can be insulated to a great extent from climate variabilities through two or three critical irrigations, complemented in each case by appropriate crop systems and in situ water conservation. In such a scenario, provision needs to be made for just about 100–150 mm of additional water, rather than large quantities, as in conventional irrigation.

Lal (2012) provides a comprehensive list of options for increasing green water in rainfed farming:

(i) increase water infiltration; (ii) store any runoff for recycling; (iii) decrease losses by evaporation and uptake by weeds; (iv) increase root penetration in the subsoil; (v) create a favorable balance of essential plant nutrients; (vi) grow drought avoidance/adaptable species and varieties; (vii) adopt cropping/farming systems that produce a minimum assured agronomic yield in a bad season rather than those that produce the maximum yield in a good season; (viii) invest in soil/land restoration measures (i.e., terraces and shelter belts); (ix) develop and use weather forecasting technology to facilitate the planning of farm operations; and (x) use precision or soil-specific farming technology using legume-based cropping systems to reduce losses of Carbon and Nitrogen and to improve soil fertility. Similarly, growing crops and varieties with better root systems is a useful strategy to reduce the risks in a harsh environment. The root system is important to drought resistance.

This kind of approach to rainfed areas, with a strengthening of the agricultural extension system on a participatory basis, would make a major contribution to the paradigm shift needed in farming to solve India’s water problem.

Clearly, there is robust scientific support for exploring alternatives to Green Revolution farming, which needs to be an essential part of the response to both the crises of water and agriculture in India. However, there is also a need to make a strong argument against any kind of fundamentalism on both sides. Those who insist on business-as-usual are being fundamentalist and irresponsible because they are turning a blind eye to the distress of India’s farmers and the grave water crisis in the country. On the other hand, it is also important that those working for alternatives adopt procedures for transparent verification and evaluation of their efforts. What is more, the efforts will need multiple forms of support from the government, similar to the multi-pronged approach adopted at the time of the Green Revolution. We would like to propose a few essential steps here:

-

Building on the intuition of the Hon’ble Prime Minister who initiated the Soil Health Card Scheme, the soil testing capacities of the entire country need to be urgently and comprehensively ramped up. This means not only establishing more soil testing laboratories, but also testing on a much wider range of parameters, based on the `living soils’ vision, where testing is extended to the 3Ms (moisture, organic matter and microbes). This will make it possible to assess over time whether the claims of different farming approaches can be validated as being truly ‘regenerative’ and for an assessment to be made about the kinds of interventions that may or may not be required in each specific context.

-

Widespread and affordable facilities must be made available for testing the maximum residue level of chemicals in farm produce, in line with regulations of the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI), without which there will be no guarantee that the produce meets required health safety standards.

-

This also requires large-scale and separate processing, storage and transport facilities for the produce of ‘natural farmers’ so that it does not get contaminated by the produce of conventional chemical farmers. Storage of pulses needs careful attention to moisture and temperature. Dry and cool pulses can be stored for longer periods. This demands major investments in new technologies that are now easily available. For crops like millets, processing remains an unaddressed challenge. Therefore, millet-processing infrastructure needs to become a priority, to incentivise farmers to move to water-saving crops and also to move them up the value chain.

-

The present farm input subsidy regime that incentivises production with a high intensity of chemical inputs must shift to one that supports the production of organic inputs and provides payment for farm ecosystem services, like sustainable agriculture practices, improving soil health etc. This can, in fact, become a way to generate rural livelihoods, especially if the production of organic inputs could be taken up at a large scale by federations of women SHGs and farmer producer organisations (FPOs).

-

The SHG-bank linkage would also be crucial in order to ensure that credit actually reaches those who need it the most and whose dependence on usurious rural moneylenders grew after strict profitability norms were applied to public sector banks in 1991 (Shah, 2007). Shah et al. (2007) explain how SHGs led by women enable these banks to undertake sound lending, rather than the botched-up, target-driven lending of the Integrated Rural Development Programme (IRDP) in the years following bank nationalisation. The SHG-Bank Linkages Programme has not only benefitted borrowers, but has also improved the profitability of many bank branches in rural and remote areas, thus mitigating the inclusion-profitability dilemma that afflicted public sector banks in the first two decades after nationalisation. As a result, formal rural credit has once again made a comeback during the last decade, after a period of decline in the 1990s and early 2000s. Such credit support will be crucial if the paradigm shift in farming proposed in this chapter is to be scaled up on the ground.

-

Finally, the entire agricultural extension system needs to be rejuvenated and revamped, to make it align with this new paradigm. Special focus must be placed on building a whole army of Community Resource Persons (CRPs), farmers trained in all aspects of agroecology, who would be the best ambassadors of this fresh perspective and understanding, working in a truly `rhizomatic’ manner, allowing for multiple, non-hierarchical points of knowledge representation, interpretation and sharing.Footnote 46

Thus, to carry forward the agroecological revolution in India, there is a need for an overarching architecture very similar to the one that propelled the Green Revolution in its heyday, even though each of its constitutive elements would be radically different. It is only if the pattern of subsidies is changed and these reforms are put in place by the government that the paradigm shift in farming proposed in this paper will be able to take off in real earnest. Otherwise doubts about its authenticity and power could remain.

5 The Paradigm Shift Required in Water

This section relies heavily on both Shah (2013) and Shah et al. (2016), where these arguments are fleshed out in fuller detail.

Just as the Green Revolution paradigm fundamentally misrecognises the essential nature of soils as living ecosystems, the dominant policy discourse on water fails to acknowledge the principal characteristics of water as an intricately inter-connected, common pool resource. The multiple crises of water in India today could be said to stem from this essential misapprehension. Atomistic and competitive over-exploitation of aquifers and the inability to manage catchment and command areas of large dams are the biggest examples of how the water crisis has got aggravated.

What makes things worse—but also creates an opening for a new beginning—is the fact that definite limits are being reached for any further construction of large dams or groundwater extraction. Thus, the strategy of constructing large dams across rivers is increasingly up against growing basin closure. In addition, the possibilities of further extraction of groundwater are reducing, especially in the hard rock regions, which comprise around two-thirds of India’s land mass. This is why the Twelfth Five Year Plan clearly spoke of the need for a fundamental shift from more and more construction of dams and extraction of groundwater, towards sustainable and equitable governance and management of water.

5.1 Participatory Irrigation Management in the Irrigation Commands

India has spent more than INR 4 trillion on the construction of dams, but trillions of litres of water stored in these reservoirs is yet to reach the farmers for whom it is meant. There is a growing divergence between the irrigation potential created [113 million hectares (mha)] and the irrigation potential actually utilised (89 mha). While this gap of 24 mha reflects the failure of the irrigation sector, it is also low-hanging fruit: by focusing on this, India can quickly bring millions of hectares under irrigation. Moreover, this can be achieved at less than half the cost of building new dams, which are becoming increasingly unaffordable. There are massive delays in the completion of projects and colossal cost over-runs of, on an average, 1382% in major projects and 325% in medium dams (Planning Commission, 2013), in addition to which there are humongous human and environmental costs.Footnote 47

Major river basins like Kaveri, Krishna, Godavari, Narmada and Tapti have reached full or partial basin closure, with few possibilities of any further dam construction. In the Ganga plains, the topography is completely flat and storages cannot be located there, as they would cause unacceptable submergence. Further north in the Himalayas—comparatively young mountains with high rates of erosion—the upper catchments have little vegetation to bind the soil. Rivers descending from the Himalayas, therefore, tend to have high sediment loads. There are many cases of power turbines becoming dysfunctional because of the consequent siltation. Climate change is making the predictability of river flows extremely uncertain. Diverting rivers will also create large dry regions, with adverse impact on local livelihoods. The neo-tectonism of the Brahmaputra valley, and its surrounding highlands in the eastern Himalayas, means that modifying topography by excavation or creating water and sediment loads in river impoundments can be dangerous. Recent flooding events in Uttarakhand and Nepal bear tragic testimony to these scientific predictions.

There is, therefore, an urgent need for reforms focused on demand-side management, jettisoning the over-emphasis on ceaselessly increasing supply. These reforms have already been tried and tested in many countries across the globe. There are also significant successful examples of reform pioneered within India in command areas like Dharoi and Hathuka in Gujarat, Waghad in Maharashtra, Satak, Man and Jobat in Madhya Pradesh, Paliganj in Bihar and Shri Ram Sagar in Andhra Pradesh. These successes have now to be taken to scale.

Reforms in this context imply a focus on better water management and last-mile connectivity. This requires the de-bureaucratisation or democratisation of water. Once farmers themselves feel a sense of ownership, the process of operating and managing irrigation systems undergoes a profound transformation. Farmers willingly pay irrigation service fees to their Water Users Associations (WUAs), whose structure is determined in a transparent and participatory manner. Collection of these fees enables WUAs to undertake proper repair and maintenance of distribution systems and ensure that water reaches each farm.

This kind of participatory irrigation management (PIM) implies that the State Irrigation Departments only concentrate on technically and financially complex structures, such as main systems, up to secondary canals. The tertiary-level canals, minor structures and field-channels are handed over to the WUAs, which enables better last-mile connectivity and innovative water management. This includes appropriate cropping patterns, equity in water distribution, conflict resolution, adoption of water-saving technologies and crop cultivation methods, leading to a rise in India’s overall water-use efficiency, which is among the lowest in the world.

PIM, it must be acknowledged, is not a magic bullet; studies across the world reveal specific conditions under which it works. These need to be carefully adhered to. While these are issues for state governments to tackle, the Centre also has a critical role to play in incentivising and facilitating the former to undertake these reforms. Release of funds to states for large dam projects must be linked to their progress on devolutionary reforms and empowering WUAs. States committed to the national goal of har khet ko paani (water for every farm) will not view this as an unreasonable imposition. In order to allay any apprehensions, the Centre should also play an enabling role, helping officers and farmers from different states to visit pioneering PIM proofs-of-concept on the ground sites, so that they can learn and suitably adapt them to their own command areas.

5.2 Participatory Groundwater Management

In a classic instance of vicious infinite regress,Footnote 48 tubewells—which were once seen as the solution to India’s water problem—have tragically ended up becoming the main cause of the crisis. This is because borewells have been indiscriminately drilled, without paying attention to the nature of aquifers or the rock formations within which the groundwater is stored. Much of India is underlain by hard rock formations, with limited capacity to store groundwater and very low rates of natural recharge. Once water is extracted from them, it takes very long for them to regain their original levels.

For decades, aquifers have been drilled everywhere at progressively greater depths, lowering water tables and degrading water quality. It is also not often understood that over-extraction of groundwater is perhaps the single most important cause of the peninsular rivers drying up. For these rivers to keep flowing after the rains stop, they need base-flows of groundwater. But when groundwater is over-extracted, the direction of these flows is reversed and ‘gaining’ rivers get converted into ‘losing’ rivers. Springs, which have historically been the main source of water of the population in mountainous regions, are also drying up in a similar way.

Reversing this dire situation requires a careful reflection on the nature of groundwater and a recognition that it is a common-pool resource. Groundwater, by its very nature, is a shared heritage. While the land under which this water is located can be divided, it is not possible to divide the water, a fugitive resource that moves in a fluid manner below the surface. Competitive and individual extraction leads to a mutually destructive cycle, where each user tries to outdo the others in drilling deeper and deeper, till the point where virtually no groundwater left. Indeed, this point is being reached in many aquifers in India today. How, then, can India protect and continue to use its single most important natural resource without driving it to extinction?

One commonly proposed solution is to metre and licence the use of groundwater. While this might make sense for the few very large consumers, such as industrial units, it would be impossible to implement on a large-scale, bearing in mind that India has more than 45 million wells and tubewells. Fortunately, there are a few examples that show the way forward. A million farmers in the hard rock districts of Andhra Pradesh have come together to demonstrate how groundwater can be used in an equitable and sustainable manner (World Bank, 2010). With the co-operation of hydro-geologists and civil society organisations, facilitated by the government, these farmers clearly understood the nature of their aquifers and the kinds of crops that could be grown with the groundwater they had. Careful crop-water budgeting enabled them to switch to less water-intensive crops, more suited to their specific agroecology. It needs to be noted that this initiative required a strong mooring in both science and social mobilisation. Such examples have mushroomed all over India, especially in Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, Kutch and Sikkim. All of them are based on collective action by farmers, who have come together to jointly manage their precious shared resource. They have developed protocols for pumping of water, sequencing of water use as well as distance norms between wells and tubewells, and strictly adhere to them, once they understand that this is the only way they can manage to meet both their farm and domestic requirements.

Taking these innovations to scale requires massive support from the government. Paradoxically, as groundwater has become more and more important, groundwater departments, at the Centre and in all the states, have only become weaker over time. This trend needs to be reversed urgently and state capacities strengthened in a multi-disciplinary manner. The Twelfth Plan saw the initiation of the National Aquifer Management Programme and the government recently launched the Atal Bhujal Yojana (Atal Groundwater Scheme).Footnote 49 While both of these are pioneering initiatives, the likes of which the world has never seen before, they are yet to take off. The primary reason is that the requisite multi-disciplinary capacities are missing within government. Besides, they cannot be implemented by the government alone. They demand a large network of partnerships with stakeholders across the board: universities, research centres, panchayati raj institutions and urban local bodies, civil society organisations, industry and the people themselves.

5.3 Breaking the Groundwater-Energy Nexus and Legal Reform

It is also necessary to break the groundwater-energy nexus that has only encouraged the mining of groundwater by making both power and water virtually free for the farmers. The solution cannot be marginal cost pricing, which would have an extremely adverse impact on the access to groundwater for millions of small and marginal farmers and endanger their livelihoods. We cannot afford to kill the goose that lays the golden egg (WLE, 2015). A possible way forward could be to emulate the Jyotigram Yojana (Village Lighting Scheme) of the Government of Gujarat, through the separation of power feeders. The key here is the rationing of high-quality power to farmers for eight hours. Many states have now followed Gujarat’s example, with different hours of rationing: Punjab (five hours), Rajasthan and Karnataka (six hours), Andhra Pradesh (seven hours), Haryana, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu (nine hours). While the jury is still out on the effectiveness of this measure in containing groundwater use, a recent study by Ryan and Sudarshan (2020) seems to suggest that it might be working well.

Concomitantly, urgent legal reform is required because groundwater continues to be governed by British common law of the nineteenth century, whose provisions seriously limit access to groundwater for small and marginal farmers. The common-law doctrine of absolute dominion gives landowners the right to take all water below their own land. The legal status of groundwater is effectively that of a chattel to the land. When water is extracted from below the land, the principle of damnum absque injuria (damage without injury) legally sanctifies unlimited volumes of abstraction, which can adversely impact water levels in neighbouring wells or tubewells.

The science of hydrogeology explains that water flowing underneath any parcel of land may or may not be generated as recharge on that specific parcel. Recharge areas for most aquifers are only a part of the land that overlies the entire aquifer. Hence, in many cases, water flowing underneath any parcel of land will have infiltrated the land and recharged the aquifer from another parcel, often lying at a distance. When many users simultaneously pump groundwater, complex interference results between different foci of pumping, which is a common feature in many parts of India, where wells are located quite close to one another. This is typically how water tables have plunged and there is no legal protection available against such consequences, thereby endangering the lives and livelihoods of millions of farmers.

The Government of India has drafted a Model Groundwater (Sustainable Management) Bill, 2017 (Cullet, 2019). It should be formally approved, so that state governments can use this model to adopt groundwater legislation giving priority to protection measures at the aquifer level and an access framework centred on ensuring the realisation of equitable and sustainable groundwater management and governance.

5.4 Protecting and Rejuvenating India’s Catchment Areas

There is a pressing need to understand that the health of the country’s rivers, ponds and dams is only as good as the health of their catchment areas. In order to protect the country’s water sources, the areas from where they `catch’ their water need to be protected and rehabilitated.

A 2018 study of 55 catchment areas (Sinha et al., 2018) shows that there has been a decline in the annual run-off generated by major river basins, including Baitarni, Brahmani, Godavari, Krishna, Mahi, Narmada, Sabarmati and Tapi, and this is not due to a decline in rainfall but because of economic activities destructive of their catchment areas. The fear is that if this trend continues, most of these rivers will almost completely dry up.

All over the world, including in China, Brazil, Mexico, Costa Rica and Ethiopia, attempts are being made to pay for the ecosystem services provided for protecting catchment areas, keeping the river basin healthy and green. If the channels through which water flows into rivers are encroached upon, damaged, blocked or polluted, the quantity and quality of river flows are adversely affected. The natural morphology of rivers has taken hundreds of thousands of years to develop. Large structural changes to river channels can lead to unforeseen and dangerous hydrological, social and ecological consequences.

How, then, is the imperative of economic development and its negative impacts on water availability and river flows to be reconciled? This is possible only by adopting a completely different approach to development—one where interventions are woven into the contours of nature, rather than trying to dominate it. Most of India gets its annual rain within intense spells in a short period of 40–50 days. The speed of rainwater as it rushes over the ground needs to be reduced by carefully regenerating the health of catchment areas, treating each part in a location-specific manner, as per variations in slope, soil, rock and vegetation. Such watershed management helps recharge groundwater and increase flows into ponds, dams and rivers downstream. This can generate multiple win-wins: soil erosion is reduced, forests regenerated, water tables rise, rivers are rejuvenated, employment generated, farmer incomes improve, thereby reducing indebtedness, and bonded labour and distress migration gradually eliminated. The most important success factor is building capacities among the local people so that they can take charge of the watershed programme from planning, design and implementation right up to social audit. The Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) scheme must be recast on a watershed basis and its enormous resources used for watershed and river rejuvenation, as also for the restoration of traditional water harvesting systems that still exist in so many parts of India, even if in a state of decay and disrepair.

This regenerative work must be integrated with groundwater-related demand management initiatives, for it is groundwater base-flows that keep rivers flowing after the monsoon. River catchments and aquifers must be always managed together within a river basin protection programme. Fundamentally, what all of this demands is bottom-up participatory management in every river basin in India.

5.5 Building Trans-Disciplinarity in Water

Both at the Centre and in the states, government departments dealing with water resources include professionals predominantly from the disciplines of civil engineering, hydrology and hydrogeology. There is an urgent need for them to be equipped with multi-disciplinary expertise covering all the disciplines relevant to the paradigm shift in water management that this chapter proposes. This multi-disciplinary expertise must also cover water management, social mobilisation, agronomy, soil science, river ecology and ecological economics. Agronomy and soil science would be needed for effective crop water budgeting, without which it will not be possible to align cropping patterns with the diversity of agroecological conditions. To develop practices to maximise the availability and use of green water, soil physical and plant biophysical knowledge will need to be harnessed. What will also be needed is a better understanding of river ecosystem dynamics, including the biotic inter-connectedness of plants, animals and micro-organisms, as well as the abiotic physical and chemical exchanges across different parts of the ecosystem. Ecological economics would enable the deep understanding and necessary valuation of the role of ecosystem services in maintaining healthy river systems. Without an adequate representation of social science and management expertise, sustainable and equitable management of water resources to attain democratisation of water will not be possible. Social science expertise is also required to build a respectful dialogue and understanding of the underlying historical cultural framework of traditions, beliefs and practices on water in a region-specific manner, so that greater learning and understanding about water could be fostered.

Since systems such as water are greater than the sum of their constituent parts, understanding whole systems and solving water problems necessarily requires multi-disciplinary teams, engaged in inter-disciplinary projects, based on a trans-disciplinary approach, as is the case in the best water resource government departments across the globe.

5.6 Overcoming Hydro-schizophrenia

Water governance and management in India has generally been characterised by three kinds of hydro-schizophrenia: that between (a) surface and groundwater, (b) irrigation and drinking water and (c) water and wastewater.

Government departments, both at the Centre and in the states, dealing with one side of these binaries have tended to work in isolation from, and without co-ordination with, the other side. Ironically, groundwater departments have tended to become weaker over time, even as groundwater has grown in significance in India. A direct consequence of surface water and groundwater being divided into watertight silos has been that the inter-connectedness between the two has neither been understood nor taken into account while understanding emerging water problems. For example, it has not been understood that the post-monsoon flows of India’s peninsular rivers derive from base-flows of groundwater. Over-extraction of groundwater in the catchment areas of rivers has meant that the many of the larger rivers are shrinking and many of the smaller ones have completely dried up. A reduction in flows also adversely affects river water quality. Treating drinking water and irrigation in silos has meant that aquifers providing assured sources of drinking water tend to get depleted and dry up over time, because they are also used for irrigation, which consumes much higher volumes of water. This has had a negative impact on the availability of safe drinking water in many parts of India. When the planning process segregates water and wastewater, the result generally is a fall in water quality, as wastewater ends up polluting supplies of water. Moreover, adequate use of wastewater as a resource to meet the multiple needs of water is not sufficiently explored.

Without bridging these silos into which we have divided water, it will be impossible to address the grave water challenges facing the country.

5.7 Building Multi-stakeholder Partnerships

The paradigm shift in water can only be built on an understanding that wisdom relating to it is not the exclusive preserve of any one sector or section of society. It is imperative, therefore, that the Central and state governments take the lead in building a novel architecture of enduring partnerships with the primary stakeholders of water.Footnote 50