Abstract

The function of sanitation is to control the fate of human waste. A toilet is only the entrance to sanitation, and human waste as materials need to be appropriately handled throughout a sanitation service chain to control the impact of human waste on the environment. While the toilet has a private aspect, post-toilet sanitation has a public aspect. It is unclear how individuals and society should share the impact of post-toilet sanitation. Sanitation enabling the use of human waste may have greater material, socio-cultural, and health impacts in society than sanitation that does not enable the use of human waste. If the impacts caused by sanitation are unreasonable, sanitation will not be sustainable. Designing a sanitation service chain is traditionally an engineering-based business that optimizes these impacts, especially from the material and health aspects. However, in the real world, the system with the maximum benefit and minimum burden as a total for society is not necessarily preferred by all individual stakeholders. Rather than simply adjusting stakeholders’ interests, sanitation may actively establish appropriate relationships with each stakeholder, even on an individual level, to be more sustainable. Such a design approach would go beyond the traditional design approaches of sanitation optimization that use conventional engineering tools.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Sanitation as a System and a Service Chain to Deal with Material

The definition of the word sanitation is “the protection of public health by removing and treating waste, dirty water, etc.” (Pearson (a)) or “the equipment and systems that keep places clean, especially by removing human waste” (Oxford University Press (a)). From a material standpoint, the primary function of sanitation is to handle waste, especially human waste (i.e., human excreta, containing feces and urine). The purpose of sanitation is to clean places and protect public health by adequately handling human waste. Hence, the starting point of the discussion on sanitation should be the quantity and composition of human waste.

Although there are significant individual differences, a study reported that people excrete about 128 g of feces and 1.42 L of urine every day (Rose et al. 2015). At first glance, these numbers may not seem large. However, a simple calculation shows that a community of 1000 people daily produces 128 kg and 1420 L of feces and urine, respectively; similarly, and a city of 1,000,000 people produces 128 tons and 1420 m3 of feces and urine, respectively. In addition, a person’s daily human waste contains 58 g of biochemical oxygen demand (BOD, an indicator of biodegradable organics), 11 g of nitrogen, and 1.0 g of phosphorus (Matsui et al. 2001). Accordingly, a city of 1,000,000 people generates 58 tons of BOD, 11 tons of nitrogen, and 1.0 tons of phosphorus in human waste.

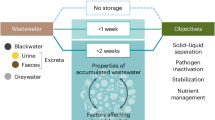

Sanitation aims to tackle a tremendous task when addressing large amounts of human waste generated by people and the materials in it. Sanitation is a complex system of multiple interrelated elements functioning together to achieve this task. The service that realizes sanitation is called sanitation service. A sanitation service chain is a chain of stages in which the service is provided. The sanitation service chain comprises five stages: containment, emptying, transport, treatment, and disposal/end-use (World Bank Water Supply and Sanitation Program 2014) as shown in Fig. 10.1.

As indicated by the sanitation service chain, sanitation involves moving materials and changing its form. For example, sanitation transports human waste and changes it into compost. Sanitation is not just a toilet, and a toilet is only a part of the sanitation system and only the entrance to the sanitation service chain. Correspondingly, the global sanitation indicator of access to sanitation facilities in the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) (United Nations 2003) has been expanded in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to include access to safely managed sanitation services (United Nations 2015). In other words, the scope of sanitation in the context of global indicators was enlarged from mere toilets to the fate of human waste in the socio-culture, including what happens after the toilets, to cover the entire area that sanitation needs to tackle fundamentally (World Bank Citywide Inclusive Sanitation (CWIS) Initiative 2021; Harada et al. 2016). Accordingly, the meaning of “sanitation” significantly changed from the toilet in MDGs to sanitation in the SDGs.

2 Toilet and Post-Toilet Sanitation

One of the characteristics of sanitation is that it aims to control the quality of a place or environment. The meaning of hygiene in dictionaries is “the practice of keeping yourself and the things around you clean in order to prevent diseases” (Pearson (b)) or “the practice of keeping yourself and your living and working areas clean in order to prevent illness and disease” (Oxford University Press (b)). Thus, hygiene is the practice of cleaning oneself and one’s immediate surroundings. Handwashing, which is a hygiene target of the SDGs, concerns cleaning dirt on the hand surface. Cleanliness of the hand surface can be achieved by handwashing. In contrast, as shown in Fig. 8.1 of Chap. 8, the object that sanitation addresses is human waste. The function of sanitation is to control the fate of human waste, thereby preventing contamination of the place or environment caused by the discharge of human waste. The toilet is directly related to one’s act of excretion, and the toilet is often one’s private property. Therefore, at the toilet level, sanitation is a private matter. However, sanitation is not something that makes oneself clean. Sanitation control resulting from adequate handling of human waste affects the environment.

Figure 10.1 shows the three typical sanitation systems along sanitation service chains. For self-sustained toilets where human waste can be treated and disposed of/used on-site, the sanitation service chain employs three stages: containment, treatment, and disposal/end-use. All these components stay in/around a toilet. In this case, the sanitation service chain is operated by toilet users, and sanitation has a strong private aspect. In the case of on-site sanitation with fecal sludge management (e.g., a pit latrine and a water flush toilet with a septic tank), emptying is conducted at a toilet and sanitation is a private matter for toilet users until the human waste accumulated in the sanitation facility (i.e., fecal sludge) is emptied. However, right after emptying at a toilet, transport, treatment, and disposal/end-use are post-toilet sanitation occurrences that extend beyond in/around-toilet sanitation. Similarly, in the case of piped sanitation (e.g., sewerage), the sanitation service chain extends beyond in/around-toilet sanitation after containment (after water flushing). In these two cases, post-toilet sanitation does not directly affect the person using the toilet. It is the business of individuals other than toilet users, and post-toilet sanitation negatively impacts the environment and/or the people involved in post-toilet sanitation. Hence, post-toilet sanitation extends beyond private matters and has a strong public aspect. In many low- and middle-income countries, public systems for the emptying, transport, treatment, and disposal/end-use of human waste are not particularly well developed, often resulting in dumping human waste and negatively impacting the environment and public health (Harada et al. 2016).

Thus, while toilet use is a private matter, post-toilet sanitation use is a public matter. If this is the case, it might not always be rational to cover all post-toilet sanitation with personal expenses. Hence, it is unclear how individuals and society should share the responsibility and burden of sanitation development and operation. Furthermore, while the toilet itself needs to be socio-culturally accepted by the individual, post-toilet sanitation needs to be accepted by society. The sanitation service chain is often established beyond the individual or even the community, and that is where human waste is emptied, transported, treated, and disposed of/used off-site. The location of each stage of the service chain will be different, and thus, the stakeholders involved will be diverse.

It is necessary to ensure that human waste is appropriately managed throughout the sanitation service chain to control the impact of human waste on the environment. For example, human waste needs to be adequately contained in the toilet, transported without dumping, and converted to a safe material for the environment. This series of processes is financially viable; however, due to the relationship between individuals and the public in the society and the multiple stages of the sanitation service chain involving various stakeholders, some stages of the sanitation service chain are not often socio-culturally established and therefore malfunction. Thus, the relationship between sanitation materials handling and socio-culture becomes complex.

3 Human Waste Use and Socio-Culture

The object of sanitation, from a material standpoint, is waste material. In reality, it contains organic and nutrient-rich material along with pathogens. The conventional sanitation service chain handles human waste as pollutants, converts it into harmless materials, and returns it to the environment. However, the material value of human waste has been recognized for a long time. For example, in Japan, human waste had historically been used as a valuable fertilizer. The system to use human waste became sophisticated in the Edo era (1603–1868), where farmers paid to collect human waste and use it for agriculture (Japan Association of Drainage and Environment–Night Soil Research Team 2003). The farmers and human waste collectors bore the financial burden of the post-toilet sanitation service chain in exchange for the fertilizer value, and the sanitation service chain functioned beyond a community without any public financial burden. This relationship worked because the benefits of human waste as fertilizer to the farmer outweighed the farmer’s and collector’s burden of collecting and transporting human waste.

Unfortunately, this self-sustaining cycle has disappeared in modern Japan. However, today there are several ideas on utilizing the potential resource value of human waste to drive the sanitation service chain and thus contribute to the realization of sound material cycles of human waste. Sanitation, which allows using human waste for agriculture, is particularly considered to have four main advantages: (1) food security and poverty alleviation, (2) cost savings for farmers, (3) preventing nitrogen pollution, and (4) restoring lost topsoil (Winblad and Simpson-Hébert 2004). Various approaches have been proposed to realize these advantages, such as ecological sanitation (Winblad and Simpson-Hébert 2004), resource-oriented sanitation (ROSA 2006), and resource-oriented agro-sanitation (Funamizu 2019).

In a small, closed system where human waste produced by a household is treated at the toilet and used by the household for agricultural purposes, sanitation, including post-toilet sanitation, seems to be a personal matter. In such cases, sanitation might be established socially and culturally, at least at the individual or household level. However, as long as people are members of society, sanitation cannot be completely independent of society. For example, the attitudes of neighboring households to sanitation for agricultural use affect their acceptance of such sanitation (Uddin et al. 2014). Sanitation will always have a social and cultural impact, and thus will never be a truly individual matter.

When sanitation with human excreta has impacts beyond a household or even a community, that is, when human waste is transported, treated, and used by someone else at a different location from the generated place, the location of each stage of the service chain may be different and the stakeholders involved can be diverse. In addition to the essential requirements of the conventional sanitation service chain that does not enable human waste use, sanitation enabling human waste use with impacts beyond a household must convert human waste for use as a valuable material, such as fertilizers and compost. Farmers accept converted human waste as a valuable material. People accept agricultural products made from human excreta. These can be regarded as conditions that affect the sustainability of a sanitation service chain.

Conversely, sanitation enabling the agricultural use of excreta may affect socio-culture. Human waste trading in the Edo era in Japan provides such examples (Aratake 2015). When used for agriculture, human waste was considered goods rather than waste. Farmers and human waste (i.e., night soil) collectors in rural areas collected human waste and purchased it from urban residents (Fig. 10.2). This trading of human waste established a beneficial relationship between the urban and the rural regions as producers and consumers of human waste as fertilizer, respectively. It made the great food consumption in and growth of urban areas more sustainable. Around Osaka, which was the largest city center in west Japan, as the scale of human waste use increased, the trade in human waste became more organized. Farmers began to cooperate across villages to form a trading union to effectively negotiate and buy human waste from the urban areas. Accordingly, subcontract business for human waste trading was established, the collection rights of human wastes were transferred between groups. Conflicts among people within a village and across villages happened on the trade, and rulings were made at the magistrate’s office. This suggests that sanitation may greatly impact the socio-culture. If the impact caused by sanitation is unreasonable, sanitation will not be sustainable.

Trading of human waste around Osaka. (Reprinted from Aratake 2015 with the permission of Seibundo Publishing)

4 Stakeholders Involved in Sanitation

Various arguments have been made to design sanitation as a sustainable system that is inevitably interrelated with socio-culture. For example, sustainable sanitation (SuSanA 2008), which emphasizes sustainability across the entire sanitation service chain, calls for the following five sustainability criteria: health, environment and natural resources, technology and operation, finance and economics, and social-cultural and institutional aspects. To satisfy such criteria, stakeholder involvement has often been emphasized in sanitation planning. For example, Kalbermatten et al. (1982) suggested that the feasibility study of a sanitation program should consider users’ social preferences and involve the following stakeholders: environmental engineers/public health specialists, economists, behavioral scientists, and the community. However, the role of the community was often limited to advising the above external specialists and selecting a technology from the prepared list of feasible alternatives; this made the sanitation service chain unsustainable.

The Bellagio Principles (Schertenleib 2000), developed by the Water Supply and Sanitation Collaborative Council (WSSCC) in 2000, became a touchstone for subsequent substantial stakeholder involvement. They are composed of the four principles listed in Table 10.1. With human dignity, quality of life, and environmental security at the household level as the main issues, the Bellagio Principles state that all stakeholders, from consumers to service providers, should be involved in decision-making. This idea became the basis of several sanitation planning methodologies, such as household-centered environmental sanitation (Schertenleib 2000), sanitation 21 (IWA 2005), community-led urban environmental sanitation planning (Lüthi et al. 2011), and city-wide inclusive sanitation, CWIS (Schrecongost et al. 2020). Through these methodologies, socio-cultural considerations are now essential in establishing a sanitation system.

While it is essential for the sanitation service chain to be socially and culturally acceptable, the sanitation service chain itself impacts the socio-culture, as discussed above, especially when the service chain involves multiple stakeholders and places. From the material aspect, sanitation affects the local material cycle; for example, dumping without adequate treatment burdens the environment, while using human waste for agriculture promotes resource recycling. The material impact of sanitation on society can be expressed as indices of pollutants, nutrients, money, etc., either maximizing the benefit or minimizing the burden. Engineering tools such as material flow analysis and life-cycle assessment are used to analyze such impacts (e.g., Buathong et al. 2013; Tran-Nguyen et al. 2015; Pham et al. 2017). Such maximization and minimization are called optimization of the system. Designing a sanitation service chain is traditionally an engineering issue aimed at optimizing the impacts while ensuring the feasibility of the technology.

However, in the real world, because of the varied interests of different stakeholders, the system with the greatest benefit and the least burden is not necessarily selected. In addition, total optimality is not necessarily equal to the sum of partial optimality. The system with the maximum benefit and minimum burden for society is not necessarily a system that an individual stakeholder prefers. If sanitation planning and design exclude individuals’ benefits or preferences, the sanitation system would not function appropriately at the ground level. If sanitation is operated beyond the household level, its service chain involves different stakeholders, and some processes may cause a significant burden on a specific social group. The topic of sanitation workers in Chap. 3 of Part I was about the social and cultural burdens that a particular group had to bear to make the sanitation service chain work on a societal level. Another topic, the social allocation of sanitation-derived health risks discussed in Chap. 8 of Part II is an example of how health burdens of sanitation are not always shared equally in society.

To make sanitation sustainable, it is essential to increase overall benefits. Still, it is also necessary to establish an appropriate relationship between the sanitation system and each of the various stakeholders, even on an individual level. We may standardize stakeholders, quantify the impact on standardized stakeholders and the environment, and increase the overall benefits of the system. However, members of a stakeholder group are not homogeneous. There may be marginalized people in a group. Accordingly, we must also understand the sanitation system’s impact on each person who uses or works in the sanitation system and the impact each person has on the sanitation system. Moreover, the design of the sanitation service chain should consider the relationships between sanitation and an individual and reasonably and equitably share socio-cultural impacts throughout society. Such a design approach would go beyond the traditional design of sanitation optimization that followed conventional engineering approaches.

5 Chapter Overview

In Part III, the authors, who have a background in engineering, examine how sanitation as a material handling system relates to socio-culture and its socio-cultural impacts when introduced in a new place. First, in Chap. 11, as a case study of the relationship between sanitation technology as a public infrastructure in a city and the city’s socio-cultural environment, this chapter focuses on the development and implementation history of a new operation and control method for sewage treatment, the dual dissolved oxygen control system. The author, who is a university researcher of sewerage technology in Japan, worked on this system’s development and implementation for the past 20 years and reviewed its dynamic relationships with various stakeholders during fundamental research, technology development, and its adoption by a local government to its social acceptance. As mentioned above, recent sanitation planning has already emphasized stakeholder involvement, but it mainly concerns stakeholder involvement when introducing a sanitation technology that has already been established. This chapter shows that stakeholder involvement is not limited to the coordination of interests among stakeholders when introducing an existing technology; it shows that the dynamic relationships with various stakeholders significantly impact the development of new technology and subsequent social implementation.

Chapter 12 focuses on the cases of self-sustained, resource-oriented dry sanitation, in which human excreta are used by households that use the toilet. In contrast to Chap. 11, sanitation could be a more personal matter in these cases. The chapter considers three rural cases from Vietnam, Malawi, and Bangladesh, where many urine-diverting dry toilets were introduced on a large scale several years ago. While health is not necessarily the primary motivation for individuals to adopt sanitation (Cairncross 2004; Jenkins and Scott 2007), the resource value of human excreta can be a potential motivator. This chapter examines the relations among toilet use, excreta use for agriculture, perception of excreta values, and reasons for users’ usage decisions. The results show that the agricultural resource value of human waste alone was not always a motivator to use the resource-oriented dry sanitation facilities but was a motivator when sanitation project was linked to an organic farming project. Further, this chapter examines the socio-cultural barriers to using human waste. It shows their dynamics, potentially impacted by the physical and other socio-cultural conditions, implying that adequate physical and social conditions need to be established to promote the long-term acceptance of the use of toilets as well as human waste.

Chapter 13 also addresses resource-oriented dry sanitation. Unlike Chap. 12, it targets an urban slum and aims to establish a sanitation service chain at the community level. This chapter is based on the authors’ ongoing research and implementation project to develop a sanitation service chain in an urban slum in Indonesia, which has not yet been fully implemented. First, the authors conducted a material flow analysis in the targeted slum and clarified the significance of introducing sanitation from a material aspect. Second, employing the methodology of material flow analysis, the authors depict the motivations of the various actors involved in the sanitation service chain and develop it into a value flow network for expressing social relationships. Based on the value flow network, a sanitation service chain is co-created with various actors involved in the network so that the motivations of each are matched, rather than simply optimizing the total impact of sanitation by conventional engineering approaches. In this case, sanitation is used to connect the motivations of different groups, creating a new social network.

As described above, sanitation is not established by merely searching for the optimal conditions of materials, but it is done considering adequate embedding into socio-culture. The perspective of socio-culture is essential to establish a sanitation system and realize a sanitation service chain. It is vital to consider socio-culture dynamically and heterogeneously for developing and introducing sanitation, unlike the old approach of introducing existing sanitation technologies with socio-culture as static and standardized constraints. Understanding the relationship between materials and the socio-culture in the Sanitation Triangle and the active use of the relationship can be the key to the development, introduction, further co-creation, and proper socio-cultural embedding of sanitation, in order to address global sanitation issues.

References

Aratake K (2015) Shinyo wo meguru kinseshakai: Osaka chiki no noson to toshi (Modern society on human waste: villages and cities in Osaka Region). Seibundo Publishing, Osaka

Buathong T, Boontanon SK, Boontanon N, Surinkul N, Harada H, Fujii S (2013) Nitrogen flow analysis in Bangkok City, Thailand: area zoning and questionnaire investigation approach. Procedia Environ Sci 17:586–595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proenv.2013.02.074

Cairncross S (2004) The case for marketing sanitation. In field note, sanitation and hygiene series, water and sanitation program-Africa. The World Bank, Nairobi

Funamizu N (ed) (2019) Resource-oriented agro-sanitation systems: concept, business model, and technology. Springer, Tokyo

Harada H, Strande L, Fujii S (2016) Challenges and opportunities of faecal sludge management for global sanitation. In: Towards future earth: challenges and progress of global environmental studies. Kaisei Publishing, Tokyo, pp 81–100

IWA (2005) Sanitation 21 – simple approaches to complex sanitation. IWA Publishing, London

Japan Association of Drainage and Environment – Night Soil Research Team (2003) Toire kou, Sinyo kou (Toilet thinking, night soil thinking). Gihodo, Tokyo

Jenkins MW, Scott B (2007) Behavioral indicators of household decision-making and demand for sanitation and potential gains from social marketing in Ghana. Soc Sci Med 64:2427–2442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.03.010

Kalbermatten JM, Juius DS, Gunnerson CG, Mara DD (1982) Appropriate sanitation alternatives: a planning and design manual. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore

Lüthi C, Morel A, Tilley E, Ulrich L (2011) Community-led urban environmental sanitation planning: CLUES – complete guidelines for decision-makers with 30 tools. Eawag, Duebendorf

Matsui S, Henze M, Ho G, Otterpohl R (2001) Emerging paradigms in water supply and sanitation. In: Maksimovic C, Tejada-Guibert JA (eds) Frontiers in urban water management: deadlock or Hope. IWA Publishing, London, pp 229–263

Oxford University Press (a) Sanitation (n.d.) Oxford Learner’s dictionaries. https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com. Accessed 14 May 2021

Oxford University Press (b) Hygiene (n.d.) Oxford Learner’s dictionaries. https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com. Accessed 14 May 2021

Pearson (a) Sanitation (n.d.) Longman dictionary of contemporary english online. https://www.ldoceonline.com. Accessed 14 May 2021

Pearson (b) Hygiene (n.d.) Longman dictionary of contemporary english online. https://www.ldoceonline.com. Accessed 14 May 2021

Pham HG, Harada H, Fujii S, Nguyen PHL, Huynh TH (2017) Transition of human and livestock waste management in rural Hanoi: a material flow analysis of nitrogen and phosphorus during 1980–2010. J Mater Cycles Waste Manage 19:827–839. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10163-016-0484-1

ROSA (2006) Resource-oriented sanitation concepts for peri-urban areas in Africa: a specific target research project funded within the EU 6th framework programme sub-priority, annex I – “description of work”

Rose C, Parker A, Jefferson B, Cartmell E (2015) The characterization of feces and urine: a review of the literature to inform advanced treatment technology. Crit Rev Environ Sci Technol 45:1827–1879. https://doi.org/10.1080/10643389.2014.1000761

Schertenleib R (2000) The bellagio principles and a household centered approach in environmental sanitation. In: ECOSAN: closing the Loop in wastewater management, proceedings of the international symposium, Bonn, 30–31 Oct 2000. GTZ, Bonn, pp 30–31

Schrecongost A, Pedi D, Rosenboom JW, Shrestha R, Ban R (2020) Citywide inclusive sanitation: a public service approach for reaching the urban sanitation SDGs. Front Environ Sci 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2020.00019

SuSanA (2008) Towards more sustainable sanitation solutions: SuSanA vision document. Sustainable Sanitation Alliance 2

Tran-Nguyen QA, Harada H, Fujii S, Pham NA, Pham KL, Tanaka S (2015) Preliminary analysis of phosphorus flow in Hue Citadel. Water Sci Technol 1–21. https://doi.org/10.2166/wst.2015.463

Uddin SMN, Muhandiki VS, Sakai A, al Mamun A, Hridi SM (2014) Socio-cultural acceptance of appropriate technology: identifying and prioritizing barriers for widespread use of the urine diversion toilets in rural Muslim communities of Bangladesh. Technol Soc 38:32–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2014.02.002

United Nations (2003) Implementation of the United Nations millennium declaration. Report of the Secretary-General

United Nations (2015) Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development

Winblad U, Simpson-Hébert M (eds) (2004) Ecological sanitation, revised and enlarged edn. SEI, Stockholm

World Bank Citywide Inclusive Sanitation (CWIS) Initiative. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/sanitation/brief/citywide-inclusive-sanitation. Accessed 13 May 2021

World Bank Water Supply and Sanitation Program (2014) The missing link in sanitation service delivery: a review of fecal sludge management in 12 cities. Water and Sanitation Program: research brief 1–8

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Harada, H. (2022). Interactions Between Materials and Socio-Culture in Sanitation. In: Yamauchi, T., Nakao, S., Harada, H. (eds) The Sanitation Triangle. Global Environmental Studies. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-7711-3_10

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-7711-3_10

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-16-7710-6

Online ISBN: 978-981-16-7711-3

eBook Packages: Earth and Environmental ScienceEarth and Environmental Science (R0)