Abstract

The authors discuss the impact of the pandemic on the sexual and reproductive health of adolescents and young people. Adolescents and young adults (AYA) are at low risk from COVID- 19, and hence, it may be assumed that their needs do not warrant immediate attention. However, it is important to understand how the pandemic may have affected their lives. Evidence from previous humanitarian disasters in India and elsewhere suggests that consequences for adolescents and young adults may be significant and multi-dimensional. The authors examine the impact (short- and long-term) of COVID on the sexual and reproductive needs and behaviors of AYA in India, particularly their intimate relationships, sexual violence, access to services, and impact on their mental health.

Programs for AYA should be responsive to their needs, feelings, and experiences and should treat them with the respect they deserve, acknowledging their potential to be part of the solution, so that their life conditions improve and the adverse impact of the pandemic is minimized. Programs must also address the needs of vulnerable AYA like migrants, those from the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) community, persons with special needs, HIV positive youth, and those who live in poverty. It is important to understand how gender impacts the sexual and reproductive health of AYA, particularly young girls and women, in terms of restriction of mobility, increase dependence on male partners/friends/relatives, gender-based violence, control of sexuality, and the lack of privacy and confidentiality. The responses to these needs by youth-based and youth-serving organizations and the government are summarized. Recommendations are made to address prevailing gaps from a sexual and reproductive health rights and justice perspective.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has by now affected the entire world. It has highlighted the existing gaps in equitable development and re-emphasized, in a manner that we could not imagine, the need to assess our privileges—in terms of access to education, health, housing, food security, transportation, and how we treat the environment. The stay at home and isolation requirements have impacted our basic human needs of connection, relationships, physical proximity, and intimacy. Over the last eight months, a lot has been said and written about the impact of the pandemic on our lives. COVID’s impact, however, varies depending upon one’s socioeconomic position. This is crucial to note because the effect of COVID on the most vulnerable sections of society and those whose human rights are least protected is likely to be more adverse and unique.

This chapter focuses on the impact of the pandemic on adolescents and young adults (AYA) aged 10–24, in India, with reference to their sexual and reproductive health (SRH). AYA are at low risk from COVID, and hence, their needs may not seem to warrant immediate attention. However, it is important to understand how the pandemic may have affected their lives. Evidence from previous humanitarian disasters in India and elsewhere suggests that consequences for adolescents and young adults may be significant and multi-dimensional [1].

A scan of the literature available on the impact of COVID on AYA in India presents a glaring gap of evidence on how the pandemic has affected their sexual and reproductive health (SRH). Most available evidence focuses on COVID’s impact on AYA’s education, overall health and well-being, access to livelihoods, loss of agency, and decision-making. Literature also shows COVID’s impact on AYA’s reproductive health. However, this is largely limited to disruption in services due to the lockdown imposed in India on March 24, 2020, which continued for months in different forms [2].

There is a noticeable silence around sexual health of AYA during the pandemic. This is an extension of course, of the silence prevalent pre-COVID. During pre-COVID times too, access to SRH information and services for adolescents, especially unmarried adolescents in India, has always been socially stigmatized and scrutinized, resulting in limited availability and accessibility of services for sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) [3]. The reasons for this silence are known—the lack of acknowledgment of AYA as sexual beings, the stigma around adolescent sexuality and pre-marital sex, particularly in relation to unmarried adolescent girls, and the association of reproductive health with marriage and child birth [4]. Not surprisingly then, there is a lack of global estimates of the pandemic’s effect on AYA’s SRH outcomes due to the non-availability of meta-data on the SRH needs of the young, unmarried population, an invisibility largely due to stigma around pre-marital sexual activity. In India, the absence of SRH services from ‘essential’ health services during COVID amplifies this undocumented need [3].

While the immediate effects of the pandemic on AYA’s lives are visible in terms of impact on education, mobility, employment, and leisure, the pandemic’s other possible impacts on AYA’s SRH will gradually be understood. The pandemic may have medium- and long- term impacts on AYA’s basic rights and agency in terms of their health and safety [5]. It is important to note that the pandemic has put a break on many of the normative aspects of AYA’s development, a period ideally marked by increased independence and peer bonding [6]. This may affect the development trajectory of AYA.

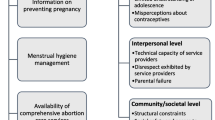

Some AYA may have been forced to enter early marriages due to the pandemic; some may have had unintended pregnancies and difficulties in accessing abortions, and some may have experienced sexual violence during this period. In addition, adolescence is also a period marked by sexual awakening within the context of lack of knowledge and guidance on sexual matters from reliable sources, which is likely to be even more limited during the pandemic. It is thus important to understand the pandemic’s impact on the SRH of AYA so that timely and adequate responses may be developed and to ensure that a crucial aspect of their lives is not overlooked (Fig. 10.1).

According to the current working definition, sexual health is

…a state of physical, emotional, mental and social well-being in relation to sexuality; it is not merely the absence of disease, dysfunction or infirmity. Sexual health requires a positive and respectful approach to sexuality and sexual relationships, as well as the possibility of having pleasurable and safe sexual experiences, free of coercion, discrimination, and violence. For sexual health to be attained and maintained, the sexual rights of all persons must be respected, protected, and fulfilled [7].

Reproductive health (RH) implies that people are able to have a responsible, satisfying, and safe sex life and that they have the capability to have children and the freedom to decide if, when and how often to do so [8].

From the above perspective, sexual and reproductive health are key factors in shaping AYA’s physical and mental well-being, factors that are often overlooked in the context of a country like India. This chapter seeks to examine the impact (short- and long- term) of COVID on the SRH needs and behaviors of AYA, based on available evidence. The chapter also highlights crucial gaps in the existing evidence and builds a case for addressing them. The authors adopt the following framework in their analysis of COVID and its impact on adolescent and young adults SRHR.

Adolescents and Young People in India

As per the Census of India 2011, every fifth person in India is an adolescent (10–19 years) and every third, a young person (10–24 years). Adolescents constituted 21.7% of the total rural population and 19.2% of the total urban population in the Census in 2011. The youth population constituted about 18.9% of the total rural population and 19.7% of the population in urban areas. For the country as a whole, the percentage of male adolescents and youth is slightly higher than their female counterparts in both rural and urban areas. In 2011, the sex ratio among the adolescent population in rural areas was 901 and in urban areas was 892. In the case of the youth, the sex ratio in rural areas was 901 and in the urban areas was 910. Recently released data from the National Family Health Survey (NFHS)-5 (2019–2020) highlights that low sex ratio continues to be a major challenge in most Indian states. NFHS-5 also highlights the gender differentials across several indicators [9]. For example, the proportion of adolescent girls (15–19) who became pregnant before age 18 ranges between 10 and 15% with wide rural/urban and interstate variation. Similarly, the experience of gender-based violence (GBV) by youth (18–29) is about 4% with minor rural/urban variation. Anemia continues to be alarming among adolescents and young adult girls in comparison with their male counterparts. Child marriage rates are still high to the tune of almost 30% in some states with large interstate and rural/urban differentials.

AYA is not an homogenous group. AYA’s needs vary with their age, sex, stage of development, and life circumstances—in terms of access to quality education, life skills development, place of residence (rural/urban), opportunities for collective learning and sharing, and the socioeconomic conditions of their environment.

As per the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), AYA in India face several development challenges, including access to quality education, gainful employment, gender inequality, child marriage, absence of youth-friendly health services, and adolescent pregnancy. These challenges have been exacerbated due to COVID [10].

A few studies, conducted during the lockdown in India, have assessed the impact of COVID on adolescents and young people in India. The Population Foundation of India (PFI) conducted a rapid assessment of the impact of COVID-19 on youth in Bihar, Rajasthan, and Uttar Pradesh [11]. Quilt Al conducted a study on the impact of COVID on adolescent reproductive health, the DASRA Adolescent Collaborative collected experiences of civil society organizations working with adolescents, and the YP Foundation reached out to its adolescent and youth network spread across 25 states and six union territories of the country, to understand the impact of the pandemic on young lives [1, 12, 13]. Findings from these studies are representative of diverse communities of adolescents and young adults including informal laborers, gender and sexual minorities, young people belonging to different castes and tribal affiliations, sex workers, people living with HIV (PLHIV), substance users, and young people living in shelters and correctional homes.

These studies have highlighted the impact of COVID on AYA’s education, access to health services including sanitary pads, iron and folic acid (IFA) tablets, contraception, abortion services, nutrition, skilling and employment assistance, and mental health services. They also provide information on how the pandemic has impacted AYA of different genders. This chapter will present the sexual and reproductive health-related findings and recommendations from these studies and will highlight data gaps that need to be addressed.

Impact of COVID on AYA’s Sexual Relationships

COVID has resulted in restrictions on freedom, mobility, and socialization worldwide. This has created increased isolation. AYA have experienced increased restrictions on mobility, recreational activities, and access to support networks due to closure of schools, colleges, non-formal learning opportunities, and workplaces [1]. This has resulted in limited social engagement with their peers, guides, and mentors and in increased anxiety and loneliness [13].

Increased family time, especially in cases where AYA have been living away from home for some years, has led to greater surveillance from adults, lack of privacy, and increased likelihood of sexual abuse by family members. Personal and financial agency of adolescents and young people, especially the most vulnerable—unmarried young women, queer and trans youth, young migrants, young refugees, homeless young people, those in detention, and young people living in crowded areas such as townships or informal settlements—has been severely impeded. In a country like India where extensive parental authority is exercised over adolescents and young adults especially in the case of the unmarried, way into adulthood, one can only imagine the increase in the extent of control parents would exercise during COVID.

As said earlier, since AYA are a low-risk group for COVID, their needs are the least prioritized. It has been almost taken for granted that they would have unlimited ability to adapt to online classes, to engage in hobbies and activities to keep themselves busy, to engage with friends online and in general to stay out of adults’ way, and behave as the adults would want them to.

In all the literature around AYA in the pandemic, there is hardly any reference to or discussion of how the pandemic may have affected the romantic and sexual lives of AYA. As we already know, in India, in general there is very limited to no conversation around AYA’s romantic and sexual relationships and their sexual health. Therefore, one cannot expect anything different during the pandemic, especially when COVID-related health concerns are the only ones getting priority attention. As per DASRA [1], organizations working with AYA have often struggled with obtaining information about this aspect of AYA’s lives, and the constraints on meeting privately and in groups have further increased the challenge during the pandemic.

How are AYA engaging in intimate relationships during this time? How has the pandemic affected pre-marital sex, an open secret in India? Are AYA engaging in safe sex practices, keeping COVID precautions in mind? Who is providing them with this information and from where are they accessing it? Is sexual abuse a problem AYA are facing? These questions, particularly among unmarried AYA, are important but remain unanswered.

In the case of married AYA, there is evidence to show that some young married men are coercing their partners for sex, simply because the men are bored at home. The International Center for Research on Women (ICRW) and Vihara Innovation Fund’s rapid qualitative study to understand the impact of COVID on the family planning needs of women and men in Uttar Pradesh (UP) and Bihar showed that for some male respondents, sex was a way of releasing their stress and a distraction from their ongoing economic crisis. Female respondents of the study reported being frustrated because of the constant demands of sex by their husbands [14]. Cases of coercive sex and domestic violence might also be increasing as a result of this situation, but systematic attention has not been paid to explore this issue.

Added to these issues is the rise of digital connections in the context of sex. As per Quilt AI, in India, COVID will catalyze the digital revolution as the base of Internet users is expected to increase from 574 to 639 million by the end of 2020. Quilt AI’s study shows that more and more AYA have been spending time online, especially during the pandemic [12]. How are AYA accessing online spaces for personal connections? What about practices like online dating, sexting, virtual sex, and the associated safety-related issues? Quilt AI undertook a study to examine the impact of COVID on digital engagement on issues related to sexual and reproductive health (SRH), imparting skills to girls, and their employment. The study showed that there was an increase in searches for violent porn in towns/districts from February 2020. However, there was a gradual decline in cities. This is an important pointer toward AYA sexual behavior during the pandemic, particularly the use of online platforms for accessing porn that is violent in nature. This distinction between an increase in towns/districts and a decline in cities needs to be examined further in terms of the reasons and impact on AYA and their relationships.

It is important to recognize that the pandemic is likely to have impacted the relationships and sex lives of AYA about which little is known nor is it considered in policies and programs. Keeping in mind the social situations that might arise due to this pandemic, Banerjee and Rao explain that the probable impacts may be sexual abstinence, coercive sexual practices, non-compliance to precautions, disinterest in sex, unhealthy use of technology, interpersonal problems, rise in sexual disorders, and high-risk sexual behaviors [15]. This in turn may have impacted the already vulnerable gender dynamics, attitudes, and behaviors of AYA and their partners who may or may not be adolescents or young adults.

COVID and the Rise in Partner Violence

During COVID, adolescents and young adults, especially girls and women, may experience higher levels of violence, given the isolation and requirement to stay at home. In pre-COVID times, this population group tended to face high levels of domestic and intimate partner violence [1].

Globally, there has been increasing evidence of rising domestic violence since the lockdown, especially among women and young girls [16]. In India, it has been reported that calls seeking support against violence have been increasing since the lockdown [17]. The DASRA Adolescent Collaborative report on experiences of civil society organizations working with AYA highlights that many young people witnessed and experienced violence during the lockdown. This includes physical and sexual violence perpetrated by parents, siblings, boyfriends, and/or husbands [1]. Organizations reported to DASRA that they had been approached more often by girls in comparison with boys to report instances of physical and sexual violence [1].

Several organizations reported that many girls and young women they work with shared that their husband or boyfriend had forced them to have sex. International Council for Research on Women (ICRW) and Vihara’s study on family planning during COVID also highlighted instances of forced sex between young married couples. In studies by DASRA and YP Foundation, AYA reported that they feel unsafe at home, indicating that they may be living with their abusers. Organizations also reported continued trafficking of girls and boys during the pandemic, and in some areas, organizations reported an increase in the number of trafficking cases.

Further, limited information is available on the violence that AYA with lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, and asexual (LGBTQIA) identities may be facing. The YP Foundation highlights that LGBTQA are at increased risk of gender dysphoria, and physical and psychological violence, which is likely to be further heightened during the pandemic. A few media reports have highlighted that there has been increased discrimination against sexual minorities during the pandemic, but it is likely to be hidden in the context of India where sexual minorities are discriminated against.

As mentioned previously, AYA have been spending more time online during the lockdown. Organizations reported that more incidents of cyber bullying and use of social media to spread morphed pictures and rumors especially about girls had come to their notice. The now infamous Boys Locker Room incident from a private school in Gurgaon, Haryana, India, where male classmates created an Instagram group and were casually discussing sexual violence and rape threats against their female classmates, is one such example.

The increase in sexual and gender-based violence emphasizes the need for information and support services, response mechanisms, and access to emergency contraception and other reproductive health services. It also emphasizes the need to study the causes and impact of these increasing instances because these affect AYAs’ interpersonal relationships, gender norms among them, sexual practices, and overall mental well-being in the short as well as in the long term. Going further, this highlights the importance of finding ways to address these problems during the pandemic and ensuring that the policy and program actions have an impact post-COVID as well.

Access to Sexual and Reproductive Health Services: Growing Gap for AYA During COVID

Global media reports and research studies have highlighted that routine reproductive health services and access to supplies have been interrupted due to COVID. The majority of public health facilities in India have been converted into COVID treatment centers or have shifted their focus to managing COVID care [11]. Further, smaller clinics including private ones have been shut or have found it challenging to ensure that related precautions are in place. Diversion of infrastructure, personnel, and financial resources to COVID-related care has resulted in a shortage of supplies and other challenges in delivering health services, including reproductive health care, which was already facing challenges [11]. This has resulted in extreme difficulties, particularly for women and girls, in accessing reproductive health services, especially in the rural areas of India where they are mostly dependent on the public health system [18]. Furthermore, it has rendered any form of sexual health services, already more inaccessible than reproductive health services, more remote for young people.

Given the current situation, health services for adolescents and young adults have been generally compromised. While government guidelines specify the need to provide adolescents counseling and services through the adolescent-friendly clinics established under the Rashtriya Kishore Swasthya Karyakram (RKSK) scheme, these clinics have largely been non-operational during COVID. It is particularly troubling that even in pre-COVID times, adolescents reported that they found it difficult to access these clinics [13, 19].

In its study, DASRA explored the extent to which youth organizations faced challenges in accessing reproductive health and other healthcare services for the young. Findings from its report suggest that many youth-based organizations received feedback from young people about difficulties in accessing a range of services. Organizations reported that girls and boys had not received regular supplies of weekly iron and folic acid (IFA) tablets since the lockdown was imposed because these were dependent on schools and community health workers. Community health workers like accredited social health activists (ASHAs), anganwadi workers (AWWs), and auxiliary nurse midwives (ANMs) also confirmed this in the dialogue series organized by Women in Global Health India to amplify the voices of health workers during COVID between June–November 2020 [20].

A critical impact of COVID has been on access to sexual and reproductive health commodities and services for young people. Services like access to sanitary napkins, routine SRHR checkups, access to contraceptives, abortion services, and pregnancy-related care for adolescents and young adults were challenging even in pre-COVID times, given India’s cultural context and denial of AYA’s sexuality. During the COVID pandemic, several youth-based organizations reported that these challenges have increased [1, 13].

Though young girls reported chronic shortages of sanitary napkins, their difficulties in accessing the napkins increased significantly during the lockdown. As per DASRA and YP Foundation, sexually experienced young people expressed difficulty in accessing contraceptive supplies. This may result in unintended pregnancies. Here it is important to note that there is underreporting among sexually experienced young people of unintended pregnancies. Most unmarried sexual relationships are clandestine given the social taboos and stigma associated with pre-marital sex [4]. Organizations also reported to DASRA and YP Foundation that pregnant girls had trouble in accessing ante-natal, delivery, and post-natal care when the lockdown was imposed. Some women and girls were compelled to deliver at home.

Furthermore, access to abortion services was severely impacted in general. ICRW’s study in 2018 on Male Engagement in Pre-marital Abortions in New Delhi highlighted that most pre-marital abortions are clandestine and AYA rely on their informal networks to gather information on abortion services [4]. These networks may have become difficult to access during COVID.

COVID and the lockdown have had an unprecedented impact on women and girls’ access to abortion. Several questions remain to be answered. What services are women and girls accessing to get abortions? Who is assisting them? How is this impacting their health and well-being? International Pregnancy Advisory Services (IPAS) estimates that in India, access to medical abortions, which is what most women and girls rely on, must have become very challenging during the lockdown and the COVID pandemic, due to lack of availability, lack of information, and lack of privacy and confidentiality. As per IPAS, 1.5 million medical abortions may have been compromised in the first three months of the lockdown period. This could be due to closure of outlets, disruption of the supply chain, and restriction in transport services, since AYA women or their partners generally avoid their neighborhood chemist shops and prefer a more distant outlet for buying medical abortion drugs due to the attached stigma [18]. Furthermore, accessing an abortion at an approved facility is challenging to begin with, particularly for abortion beyond 12 weeks. However, given the impact of COVID, as per IPAS, facility-based first or second trimester abortion may be the only option for a majority of the 1.85 million women, including adolescent girls and young adult women needing abortion services [18].

Restrictions on mobility and lack of transportation facilities during COVID-19 increased these challenges. It is important to note the unique vulnerabilities of AYA during the lockdown: limited autonomy and age-related vulnerability, wherein they are often not taken seriously, particularly in India, and the lack of adolescent-centric services to begin with may have pushed their sexual health practices and contraceptive needs further underground [3]. Also, it is crucial to recognize that data on AYA’s SRHR experiences remains limited, since these are not seen as priority issues to be monitored.

While researching for this chapter, the authors noted that the limited evidence that has been collected on AYA SRHR during COVID primarily focuses on their reproductive health. Information on AYAs’ sexual health and relationships remains very limited and, therefore, invisible and non-quantifiable. It is important to address this gap because we remain unaware of the impact on AYA, most of whom, anyway, lack the legitimacy or ability to openly seek SRH services.

Mental Health of AYA During COVID and Its Links to Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights

COVID and the resulting isolation have impacted the mental health of human beings globally [21, 22]. This includes AYA more so since they are not even recognized as a group having special needs, requiring attention. DASRA’s report highlights how AYA’s mental health was impacted during COVID in India. AYA are facing high levels of anxiety and stress related to COVID, school closures, lack of socialization, and violence at home. Further, due to lack of opportunities to meet their peers and other adults whom they trust, AYA are unable to share their anxieties. They do not know who to approach with their questions and thoughts. Sexual and reproductive health issues are likely to rank quite high among these concerns.

Youth organizations reported that some young people had approached them with fears about their intimate relationships, sexual violence, about their future, and had shown symptoms of anxiety and depression and a few had also expressed suicidal thoughts. They talked about the impact of the lack of space at home, isolation from their friends and partners, and the lack of intimacy with their partners. While organizations refer to mental health and well-being of AYA, they do not have information on how the lack of access to SRHR services and information is impacting their mental health. The limited data suggests the need to explore further into this aspect.

The need for mental health services and counseling in general is paramount, including for adolescents and young people, who are further isolated since they do not have any avenues to share and learn from each other, leave alone accessing services and counseling. The effect of a worldwide pandemic on AYA’s mental health can be devastating and cannot be overlooked [23]. The potential and lives of a whole generation of young people could be impacted.

Taking Stock of Responses to Adolescents’ and Young Adults’ Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights During the Pandemic

The challenges presented above have been highlighted by youth collectives, youth-based and youth-serving organizations as seen in our review of the literature and conversations with some of these organizations. While recognizing the impact of the pandemic on AYA’s lives, these organizations also adapted their regular programs to respond to the unique needs of AYA during this time. They leveraged technology to reach AYA, trained and worked with their field staff and peer mentors to counsel adolescents remotely during the pandemic, and worked with community health workers and the public health system to address healthcare needs of adolescents.

As per DASRA, organizations leveraged digital tools like WhatsApp and Zoom, developed apps, quizzes, newsletters, and advertisements on television and radio, interactive voice response (IVR), and telephone systems to spread awareness about government-mandated information to dispel misconceptions and stigma, to learn about the feelings and experiences of AYA, and to run their SRHR programs. Some organizations adapted their sexuality education curricula to a digital mode (videos, audios, and animations) and are continuing their programs online. Organizations held creative sessions (poetry, painting, and movie screenings) to engage AYA on COVID and related issues, as well as other educational issues. Further, tele-services during the pandemic were used to provide counseling to AYA on SRHR, for example, where to access sanitary napkins and contraceptives, where young people can go for abortions, and on safe sex practices.

Organizations trained their staff to address the unique needs of AYA during this time, to connect with AYA, and understand their needs so that appropriate responses can be developed. They have also worked to provide women and girls access to sanitary napkins. Some delivered sanitary napkins to the homes of adolescent girls in rural areas and urban slums; others conducted online classes on how to make pads at home. They also helped pregnant women access ante-natal care, institutional delivery by arranging transportation, and post-natal care. They worked with community health workers to ensure that they could provide these services—IFA tablets, sanitary napkins, contraceptives, transportation for deliveries, and counseling—wherever possible. Organizations reported working with their youth leaders, peer mentors, and girl champions to reach out to AYA. For example, in the case of an unintended pregnancy, the peer mentors helped women and girls access timely abortion services.

Organizations responded to complaints of sexual violence by providing counseling through their field staff (mostly telephonic) and provided referrals to other facilities. In some cases, organizations went to the child protection committee and reported the case to the police and district or block authorities. Organizations also counseled parents about stopping early marriages, particularly of young girls, advised them to continue their education, and encouraged parents to create a space at home where adolescents could feel safe. All of these were vital before the pandemic but took on special impetus during the pandemic.

Some organizations created safe spaces to enable AYA to share their fears, anxieties, and uncertainties, both online and offline, through WhatsApp, TikTok, Instagram, and Facebook groups, and through telephonic platforms. Organizations are experimenting with online fellowship programs to build leadership and life skills. They are leveraging virtual training kits and tools developed by UNICEF and ChildLine India to check in with adolescents about their mental health. However, the issue of equitable access remains a big challenge. Many AYA do not have access or regular access to smart phones and the Internet. This is more challenging for girls and women, especially in rural areas, because the men and boys from the household control the smart phones available at home.

While all these efforts are commendable and responsive to local needs and contexts, a key gap remains—that of addressing the sexual health of AYA. Organizations have limited understanding of the sexual relationships of AYA. The challenges that they face in gathering this information increased significantly during COVID. Another gap is the issue of appropriate and gender-disaggregated data on SRHR of AYA. Organizations have not systematically collected data on how COVID has impacted AYA’s SRH. Data gathering has been sporadic and need based, which makes it difficult to capture realities accurately and to design programs to address SRH needs.

The Way Forward

The trend of not prioritizing adolescent and young adults’ sexual and reproductive health has continued during COVID. The recommendations for adolescents and young adults that SRHR experts have been making over the years remain valid and even more urgent—such as acknowledging adolescent sexuality, talking about sex from the perspective of pleasure as well as safety, ensuring sex education in schools and colleges, creating safe spaces where adolescents can share their fears, anxieties, feelings, experiences, gathering information from AYA to ensure that programs for them are responsive to their unique needs, creating peer groups of AYA, and building capacities of community health workers to respond to AYAs’ needs. In addition to continuing to persevere on earlier recommendations, the authors of this chapter would like to emphasize the following key recommendations.

First and foremost, the absence of young peoples’ voices from COVID response mechanisms set up by the government is unfortunate. It represents a dismissal of young people’s experiences and unique needs. In the task force set up by the government for COVID management, representatives from youth-based and youth-serving organizations need to be included. While the government, especially local functionaries, has benefitted from the assistance provided by youth-based organizations, their involvement in planning and developing strategies is limited and needs to be addressed.

Furthermore, while the needs of young people are deprioritized, young people from vulnerable groups—those that live in poverty, those with special needs, those from the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, and asexual (LGBTQIA) communities, and those that are disadvantaged because of their gender, caste, religion, and place of habitation—face greater challenges. Special focus should be given to the needs of young people from these groups, and their representatives should be a part of developing response mechanisms.

Gender is an obvious key factor in shaping young people’s experiences, and yet, this often goes unacknowledged. The gendered impact of the pandemic on young people’s lives, especially girls and women, needs to be central to the response. How has the pandemic fueled regressive gender norms, increased gender-based discrimination and violence against girls and women, and strengthened unequal power structures? This is a question that demands an answer because the pandemic will have long-term impacts on the lives of girls and women, especially those who have been married early, dropped out of school, experienced physical, economic, mental, and sexual violence, and been refused abortions. We cannot ignore or afford to sweep under the carpet, the long-term impact of the pandemic, in our current focus on immediate, short-term responses. For this purpose, timely and accurate data is required—data that captures the needs of various groups of AYA—unmarried and married, boys and girls, and so on—so that suitable and relevant responses can be developed.

We must adopt a human rights and social justice approach, something that is most overlooked with AYA, especially girls and women. This includes designating and planning sexual and reproductive health services for AYA, and re-allocating resources accordingly. For this, one must acknowledge adolescents’ and young adults’ sexuality as a reality. It is vital to integrate sexual well-being into the public health response for adolescents and young people.

Finally, COVID has shown the potential of technology in creating new opportunities for developing health content and disseminating it and delivering services. This must be extended to AYA’s sexual and reproductive health, which is currently limited. Also, the rise in digital sexual practices needs to be acknowledged; we cannot continue to ignore or look down on them. On the contrary, recognizing their value and reach, we must encourage safe digital sexual practices. As mentioned above, the digital divide in access to technology needs to be accounted for while developing tech-based solutions. However, despite digital inequalities, young people are more connected today than ever before, and therefore, these channels must be leveraged to their fullest potential, maintaining necessary caution. In all our efforts, we need to be sure that we are addressing the entire gamut of SRH without overlooking sexual health, as we have unfortunately tended to do.

Young people are a key resource and network, more so during a health emergency. This resource remains largely untapped. Peer group programs are particularly vital in this area. With the right training, young people can work with the health authorities to help respond to the pandemic. A healthy and empowered young population is an investment as we look beyond the pandemic.

References

Dasra. Lost in lockdown: chronicling the impact of COVID-19 on India’s adolescents; 2020.

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Guidance note on provision of reproductive, maternal, newborn, child, adolescent health plus nutrition (RMNCAH+N) services during and post COVID-19 pandemic. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; 2020.

Nanda P, Tandon S, Khanna A. Virtual and essential—adolescent SRHR in the time of COVID-19. Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters. 2020;28(1):1831136.

Kedia S, Banerjee P, Nandy A, Vincent A, Sabarwal, Kato-Wallace J. Exploring men’s engagement in abortion in Delhi. International Center for Research on Women; 2018.

UNFPA. My body, my life, my world through a COVID-19 lens. The United Nations Population Fund; 2020.

Orben A, Tomova L, Blakemore S-J. The effects of social deprivation on adolescent development and mental health. The Lancet Child and Adolescent Health. 2020;4(8):634–40.

World Health organization. Sexual and reproductive health and research including the special programme HRP. World Health Organization; 2020.

World Health Organization. Reproductive health in the Western Pacific. World Health Organization; 2020.

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. National family health survey (NFHS-5) fact sheets: Key indicators 22 states/UTs from phase-I. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; 2020.

UNFPA. Sexual and reproductive health and rights, maternal and newborn health and COVID-19. The United Nations Population Fund; 2020.

Population Foundation of India. Impact of Covid-19 on young people. Population Foundation of India; 2020.

Quilt.AI. The pandemic’s impact on young people in India. Quilt.AI; 2020.

The YP Foundation. Youth insight: informing COVID-19 relief and response with young people’s experiences. The YP Foundation; 2020.

Sharma S, Nanda S, Seth K, Sahay A, Achyut P. Couples’ contraceptive behavior and COVID-19: understanding the impact of the pandemic on demand and access. Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters; 2020.

Banerjee D, Rao TSS. Sexuality, sexual well being, and intimacy during COVID-19 pandemic: an advocacy perspective. Indian J Psychiatry. 2020;62(4):418.

Plan International. How will COVID-19 affect girls and young women? Plan International; 2020.

Shukla AK. Govt helpline platform explodes with SOS calls, 92,000 seek help on CHILDLINE in 11 days. ETGovernment.com; 2020.

IPAS Development Foundation. Compromised abortion access due to COVID-19 : A model to determine impact of COVID-19 on women’s access to abortion. IPAS Development Foundation; 2020.

National Health Mission. Adolescent health (RKSK). National Health Mission; 2020.

WGH India. WGH India dialogue series: Amplifying the engagement of female frontline health workers in India’s COVID-19 response. International Health Policies; 2020.

Javed B, Sarwer A, Soto EB, Mashwani Z. The coronavirus (COVID‐19) pandemic’s impact on mental health. Int J Health Planning Manage. 2020.

Patra S, Patro KB. COVID-19 and adolescent mental health in India. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2020; 7(12):1015.

Gundi M, Santhya KG, Haberland AJ, Zavier F, Rampal S. The increasing toll of mental health issues on adolescents and youth in Uttar Pradesh. New Delhi: Population Council; 2020.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Kedia, S., Verma, R., Mane, P. (2022). Sexual and Reproductive Health of Adolescents and Young People in India: The Missing Links During and Beyond a Pandemic. In: Pachauri, S., Pachauri, A. (eds) Health Dimensions of COVID-19 in India and Beyond. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-7385-6_10

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-7385-6_10

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-16-7384-9

Online ISBN: 978-981-16-7385-6

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)