Abstract

With the background of the experience of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) in implementing policy mix, this chapter will address recent issues and policy trade-offs faced by many economies. Among other issues are focusing on growth versus inflation, the interaction between monetary policy and the external sector, the challenges of liquidity management and the nonbanking sector, monetary policy versus fiscal policy, as well as surplus transfer to the government.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

In the last couple of years, what are the issues that we have been grappling with? What are the policy trade-offs we are facing? This chapter will answer those questions focusing on growth versus inflation, amongst others, along with the interaction between monetary policy and the external sector, the challenges of liquidity management and the nonbanking sector, monetary policy versus fiscal policy as well as surplus transfer to the government. In terms of the special issue on policy mix, I have chosen asset quality because that has been a major issue in recent times in India. I will close with the outlook as well as the key risks I would like to flag going forward.

Like many other central banks, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) issues currency, acts as a banker to the government and banks and manages foreign exchange as its core functions. The control of credit used to be an RBI function but that is no longer the case. In terms of the non-monetary functions, RBI collects a whole host of information and data on macroeconomic variables that is published on the official website. RBI is also responsible for the regulation and supervision of the banking industry as well as development and promotional activities, such as spreading the institutional reach of the financial network and promoting some social activities.

Issue 1: Growth Versus Inflation

Monetary Policy Framework: Recent Experience of Flexible Inflation Targeting (FIT)

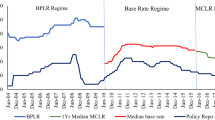

The monetary policy framework in India has evolved over time. From the 1980s until the late 1990s, RBI applied a monetary targeting approach. After the late 1990s, we used a multiple indicators approach, under which there were basically two objectives: growth and inflation. With the progress of liberalization and globalization, however, financial stability emerged as the explicit objective of the central bank. Presently, what we have is the flexible inflation targeting framework, to which we shifted in 2016 through a legislative amendment. The current objective is to maintain price stability, while keeping in mind the objective of growth. RBI adopted CPI as a nominal anchor, with the target set at 4.0 ± 2%. The interest rate path is set by the MPC, which has three external and three internal members for a total of six members. With this framework, we introduced many changes to the liquidity management framework. We did away with some refinancing schemes. We brought down the statutory liquidity ratio. Then, we implemented the bimonthly policy review cycle and biannual monetary policy report. Throughout its evolution, there has been a continuous rebalancing of weights between the different objectives of monetary policy. More so between growth and inflation. Although we have the primary objective of maintaining price stability, we must also keep in mind the objective of growth. There is always a rebalancing issue.

Why Did RBI Shift to FIT?

Since we are the latest entrant in the club of IT countries, I would like to share why RBI shifted to FIT. In India, there was a long debate about how the inflation targeting framework was not suitable for India’s case, precisely because we did not have a single price index for the country. We had four different price indexes because of the vastness of the country and diversity of regions. Second, there was an administered prices mechanism. Many of the agricultural commodities were regulated in terms of prices. This meant that the Government of India announces the minimum support prices of agricultural commodities. Under the IT framework, this would not do. Third, the high share of food in the consumption basket, which is beyond the remit of the central bank’s control. Fourth, imperfect markets. This prompted us to shift towards FIT. In terms of India's growth story, between 2003–2004 and 2007–2008, India encountered its highest growth phase, reaching nearly 9% (Fig. 10.1). At the same time, the country went through a phase of low inflation of less than 5% (Fig. 10.2). Post crisis, however, signs of stagflation suddenly appeared, namely low growth coexisting with high inflation. Consequently, RBI began to wonder what was wrong with its policy framework. It was precisely during Raghuram Rajan’s time that we set up a committee which deliberated extensively and recommended FIT. At that time, in 2011, India also launched a single price index, which provided further grounds for the shift towards FIT.

Outcomes Under FIT

We adopted FIT in 2016 and inflation has continuously been brought down since then from close to 11% to just 2.5% now, while India has maintained growth at 7%. This has greatly enhanced the effectiveness and credibility of our monetary policy. This has also enhanced the government’s credibility because the government has committed to this target and it is part of this agreement. Therefore, this indicates government commitment to fiscal prudence and reducing the burden on monetary policy. Food has a high contribution to headline CPI inflation, followed by fuel and light (Fig. 10.3).

Monetary Policy Operating Procedure

This is the corridor we have in India. It is just 50 basis points. We have a single policy instrument, namely the repo rate and our operating target is the weighted average core money rate (WACR). Our liquidity management operations ensure that the core money rate remains closely aligned with the policy rate. Volatility is restricted by the upper and lower bounds. The upper bound is defined by the Marginal Standing Facility (MSF) and the lower bound is defined by the reverse repo rate (floor), which is the reverse repo window through which the Reserve Bank accepts surplus liquidity from the banks. That is always 25 basis points below the policy rate. The Marginal Standing Facility is the facility available for the banks to avail central bank liquidity even as normal operations are taking place. That is 25 basis points above the policy rate.

Issue II: Interaction Between Monetary Policy and External Sector

Liquidity Management

This shows how we have conducted liquidity management. We have many instruments at our command, such as fixed repo, fixed reverse repo and marginal standing facility to manage the frictional liquidity. To manage the structural liquidity, which is long-tender durable liquidity, we have open market operations and the Market Stabilization Scheme (MSS). Just to be clear, we do not use our policy corridor to manage capital flows. It is entirely an instrument of monetary policy. During a phase of high capital flows, however, we have the Market Stabilization Scheme. This is a scheme under which a separate account is opened with the Government of India and government securities are sold or bought and credited to the remaining balance of that account. This means that the Reserve Bank is not bearing the cost of the sterilization operations (Fig. 10.4).

Interaction

- Participant::

-

Do you publish the bandwidth to the public?

- Speaker::

-

Yes, it is published in every monetary policy report. It is 50 bps; 25 bps above and 25 bps below. We recently augmented our liquidity management toolkit with long-term forex swaps. To give long-tenor liquidity to the market participants, we have entered into forex swaps with the banks for three years. This means that banks will come and give dollars to the Reserve Bank and the Reserve Bank will give rupee liquidity to them. When the banks return to take the dollars, they must pay a swap premium and take back their dollars. We also have a 14-day term repo at a variable rate. Liquidity is provided for 14 days at a variable rate. We also use a reverse repo of varying tenors for fine-tuning purposes.

Before I turn to how our conduct of liquidity management was completed by the external sector, that is capital inflows, let me just tell you briefly about the Southeast Asian crisis. The biggest reason, we believe, for the Southeast Asian crisis was free capital account convertibility. At that time, the IMF was freely advocating capital account convertibility. Most of the Southeast Asian countries rapidly opened up their capital accounts. Suddenly, there were huge capital inflows but, in the process, the capital inflows were short-term in nature, which were susceptible to reversals. When a reversal happened, things came crashing down. In India, however, we went through the capital account liberalization process very cautiously. In India, it was not an event but more of a process and the process was sequenced by macroeconomic fundamentals and the sustainability of the balance of payments. Even today, India's current account is still not fully convertible. There are moderate controls but mostly it is free. FDI is free in most sectors, barring six sectors, and there are some interest rate ceilings on external commercial borrowings. We also have some sectoral caps on foreign institutional investment in government bonds and corporate bonds.

Direct Investment and Portfolio Investment

In 2018, which also includes January 2019, the FDI India received was to the extent of USD29 billion, which was higher than last year if you take into account the latest month. In terms of portfolio investment, however, capital outflows were recorded from India in 2018. This was because of concerns regarding global growth at that time, along with trade war concerns, geopolitical tensions and the rising oil price. Sudden risk-on sentiment made the capital flows go back to their home countries. In 2019, positive portfolio flows returned to India due to the dovish monetary policy stance adopted amongst central banks in advanced economies and improving sentiment (Fig. 10.5). What was the impact of the capital outflows? How did they complicate liquidity management?

Equity and Debt Flows

Among the FDI flows, equity was dominant, which is of a stable nature (Fig. 10.6).

Exchange Rate Movement

The Indian rupee came under depreciatory pressures in 2018. When the Indian rupee came under pressure, the Reserve Bank had to intervene in the foreign exchange market. Although the Reserve Bank does not control the exchange rate nor does it have any target for the exchange rate, it does intervene to bring orderly conditions in the market. The Reserve Bank had to give dollars to the market but, at the same time, this operation had to be counterbalanced by providing the liquidity to the market to avoid pressure on interest rates. These operations had to be conducted cautiously and in a calibrated way so that each would not impact the others. Since 2019, the rupiah has appreciated by around 5%, second only to the Turkish lira. Incidentally, the Indonesian rupiah has been trending on a similar path, which is quite interesting. These are all the current account deficit countries and you can see the surplus countries above.

Interaction

- Participant::

-

Do you have any target for exchange rate?

- Speaker::

-

We do not have any target for the exchange rate but we do try to minimize the volatility in the foreign exchange market. We try to contain the volatility. If too much volatility is there, it creates problems for the trading community and all sorts of other problems in the economy. Therefore, we try to contain that volatility. There is no target for the volatility. It is a judgment call.

Drivers of Liquidity Management

Due to the operations and controls, the main drivers of liquidity management in 2018 and 2019 were foreign exchange operations and domestic currency in circulation. In the first half, it was foreign exchange operations and in the second half, it was currency in circulation. These were the structural drivers but the frictional liquidity was driven by government spending (Fig. 10.7).

Issue III: Liquidity Management Versus Nonbanking Sector

Currently in India, we have more than 10,000 nonbanking financial institutions registered with the Reserve Bank of India. Although they are not very systemically important, they are widespread across the breadth of the country. The exposure to sensitive sectors is low, however. Compared to several commercial banks, nonbanking sector exposure is just around 7%. Recently, some nonbanking financial institutions came under transient pressure due to several issues. Intense pressure was building on the central bank and through the government, demanding liquidity from the central bank, asking for a special window. Based on the quality of assets, the Reserve Bank did not give them any liquidity window. What they did instead was to provide enough liquidity to the other banks so they could on-lend to the nonbanking sector. RBI did relax some norms for the NBFC sector. Earlier, they were given 100% risk weights whenever the banks were lending, but now the banks are given the freedom to take their own ratings as given by the credit rating agencies and lend to the nonbanking financial institutions. These are the challenges that we were facing from the different sectors, from the government and from the external sector in the conduct of liquidity management.

Issue IV: Monetary Policy Versus Fiscal Policy

I would like to address a few things about central bank independence. With the recent adoption of the flexible inflation targeting framework, we have the MPC, which sets the interest rate. We have instrument independence. The Reserve Bank can use any instrument at its command and at its will. The interest rate is set by an independent committee. In Indonesia, the Ministry of Finance first sets the overall macroeconomic policy and the central bank works within that. It is the same case in India. I can recall one of our former governor’s statements, “The Reserve Bank is independent within government.” It is totally independent in its operations but it has to be subservient to the broad national objectives. Parliament and the government are answerable to the public, so we are subjected to that public mandate.

Government Market Borrowing

In India, the central bank manages the domestic debt of both the central government and the provincial governments. It manages on behalf of the government by raising resources from the market. In recent years, there has been a huge government borrowing program announced by the government. It is the same case with the state governments. Consequently, the huge government borrowing program and the expected slippage in the fiscal target meant the yield remain high in 2019 (Fig. 10.8).

Transmission

In 2018, yield also remained high but because of other things. There were concerns at that time regarding the fiscal deficit, oil prices and geopolitical tensions but in 2019, yield continues to remain high. What did this do to our transmission? Here, we had a monetary policy tightening cycle up to 2019 yet since February 2019 we have followed an easing cycle. Here, the Reserve Bank of India reduced its policy rate by 25 basis points but despite the reduction in the policy rate, yield had continued to remain high because of the large government borrowing program. As a result, transmission to bank lending rates, namely the credit market, was very poor and delayed. On fresh rupee loans, the decline in interest rates was just 12% and on outstanding loans, it was just 2%. As a corollary of the government's borrowing program, monetary policy transmission was delayed. It was also clouded by some asset quality concerns but it was largely because of the government borrowing program. As we said, there has to be proper coordination between monetary policy and fiscal policy in India. Largely, it is conducted in coordination and they complement each other (Fig. 10.9).

Issue V: Surplus Transfer to the Government

In the recent past, there has been a debate in India. How much surplus transfer should go to the Government of India? The government is asking for more surplus transfer but the central bank is arguing that it needs enough capital at its disposal. That is the issue we are confronted with now. Why does the central bank need capital?

Relevance of Capital for Central Banks

Many central banks have made losses in the past. Indonesia makes an appearance on that list too. In terms of central bank independence, recapitalization by the government may be at the cost of independence. In addition, capital is required to preserve the ability of central banks to conduct public policies that may lead to losses. The last factor is market confidence. The markets should have confidence in the central bank’s monetary/exchange rate actions. It is because of these reasons that the central bank has been saying it should have enough provisions. Of course, by statute, the central bank is required to transfer the profits after making provisions for bad and doubtful assets, depreciation and contribution to staff.

After making provisions for doubtful assets plus depreciation plus contribution to staff and subordination funds, whatever remains is supposed to be transferred to the Government of India by statute. Nevertheless, this has been contended by the Reserve Bank of India, which feels it needs contingency reserves and other reserves because the central bank may incur losses due to undertaking risky operations. We are investing in the government securities of other countries and the bonds of international institutions. Between this debates, recently an expert committee has been appointed by the Government and Reserve Bank of India to examine the circumstances under which the central bank would like to hold more provisions and how much transfer it should make to the government. The jury is still out on this issue, but we are confronted with it.

Special Issue: Asset Quality of Indian Banking System

This has been a matter of great concern for us in recent times. Since post-crisis, banks in most countries, including advanced and developing economies, have experienced asset quality impairment. In other words, asset quality has deteriorated. In India, however, it was largely maintained with asset quality largely intact. Since 2012, however, the decline suddenly appeared. Asset quality has started to deteriorate. The situation worsened because before 2008, during the high-growth phase, we had a period of high credit growth (credit boom). During that credit boom period, bankers tended to relax their lending standards, leading to excessive lending. That started showing up in the latter phase and what happened in India around 2012.

Asset Quality Review (AQR)

The Reserve Bank then undertook a major exercise, an asset quality review. Under this review, the Reserve Bank supervised or closely inspected some 36 major banks based on the offsite data available. The Review examined the status of large borrower accounts through analysis of offsite data from the central repository for information on large credits (CRILC) and other data. It revealed significant divergence between the reported levels of impairment and actual positions, namely much higher than the reported levels. The banks had reported one thing, but our rigorous analysis revealed significant divergence between what we found and what was reported.

After the AQR in September 2015, asset quality has deteriorated. GNPA went up from 4% to 8% and 10% in more recent times. When the asset quality started deteriorating, credit growth dropped sharply from around 11% to just 4%. In recent times, however, efforts to resolve the asset quality problems and clean up the balance sheets have restored credit growth (Fig. 10.10).

Regulatory Steps

These are the regulatory steps we took to resolve the asset quality problems. The gist of the regulatory steps is to provide the bank’s loan restructuring options and for the banks to come up with a Prompt Corrective Action plan to turn around the distressed entities. Third, converting the unsustainable debt into equity. The regulatory steps are as follows:

Framework on Revitalizing Stressed Assets in the Economy: Early recognition of financial distress, prompt steps for resolution and fair recovery for lenders

-

Central Repository of Information on Large Credits (CRILC)—Revision in Reporting

-

Flexible Structuring of Long-Term Project Loans

-

Strategic Debt Restructuring Scheme

-

Scheme for Sustainable Structuring of Stressed Assets (S4A)

-

Prompt Corrective Action

-

The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016.

Restructuring

Providing a longer amortization period for long-term loans and periodic refinancing, for instance, in the case of unstructured loans. Due to the long gestation period, we provided a long amortization period of, say, 24 years, along with periodic refinancing every 3–5 years.

Prompt Corrective Action (PCA)

This was the most debated scheme in India and has been called into question by many lobbying circles. Under this prompt corrective action plan, the Reserve Bank monitors key indicators of commercial banks, including capital, asset quality and profitability. Any breach of risk thresholds, in terms of capital, asset quality and profitability, invokes the PCA framework. Once the PCA framework has been invoked, other restrictions are imposed on the bank. They would not be able to undertake many operations. A bank will be placed under the PCA framework based on the supervisory assessment made by the RBI. Leverage is also monitored and the key indicators tracked include CRAR/Common Equity Tier I ratio, Net NPA ratio and Return on Assets. The central bank has placed 11 commercial banks under the PCA framework. There were increasing calls from lobbyists that the norms should be relaxed. The government's emphasis is always on increasing credit, but the central bank's emphasis is always on financial stability. It is like boosting credit without regulatory forbearance, with implications on financial stability. This is the ever-present conflict between short-term vs. long-term costs and benefits. The Reserve Bank was aiming for financial stability and regulatory tightening, whereas the government and banking community were asking for forbearance.

Central Repository of Information on Large Credits (CRILC)

The essential objective of CRILC is to enable banks to take informed credit decisions and early recognition of asset quality problems. Meanwhile, CRILC is expected to play a pivotal role in activating and coordinating the mechanism to manage stressed assets. The repository only deals with large credits. It provides all the data in a consolidated form of bank exposure to different borrowers. Furthermore, we have online modules for dissemination of data on non-cooperative borrowers, facility-wise borrower exposure details, select borrowers’ asset classification and fraud classified borrowers.

Functionalities in CRILC

We categorize different special mention accounts (SMA) based on these classifications:

-

SMA-0: Not overdue for more than 30 days but with incipient signs of stress

-

SMA-1: Overdue between 31 and 60 days

-

SMA-2: Overdue between 61 and 90 days.

Once an account falls into the second category, it immediately alerts all the banks to be careful about these borrowers. No other bank should be lending to them. Corrective actions are immediately taken.

The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code 2016

This is another major bank tool we are using in India. For a long time, India did not have any legally enforceable resolution mechanism. In 2016, however, we promulgated the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code that empowers creditors to deal with the troubled entity's assets. In fact, creditors or banks can now take over the assets of borrowers and they can come up with a resolution plan. This has turned out to be quite an encouraging experience so far. According to the data, this resolution mechanism has been able to provide resolution plans to some of the large corporate debtors. The cases where liquidation has been required are higher than the cases of resolution.

Outlook: India in the World Economy

India continues to be one of or the fastest growing economies in the world. It has been there for the last 10 years. Presently, India is going through a period of demographic transition. The portion of the younger population is high in India. If we capitalize on that demographic dividend in terms of developing the infrastructure and imparting the required training and skillsets, India has tremendous potential. India has a sustainable current account deficit of 2.5% of GDP and a relatively moderate fiscal deficit of 3.5%. With such sound macroeconomic fundamentals, India has promising prospects going ahead but, as is the case with other countries, there are risks to us as well.

Interaction

- Participant::

-

Growth in India has increased compared with conditions last year. In other countries, however, GDP growth is lower. What is the source of the growth in India this year?

- Speaker::

-

Growth this year has basically been driven by domestic investment. Growth in India is primarily consumption led. There is plenty of untapped demand in India so the growth story is always dominated by domestic consumption. In recent years, however, the investment cycle has fortunately turned around and growth is currently led by investment.

Key Risks Going Forward and Outlook

-

Pace of US Fed’s rate hikes and balance sheet unwinding, as well as the spill-over effects;

-

Financial market volatility, risk-on and risk-off sentiment;

-

Trade war concerns between the United States and China;

-

Crude Oil Prices—Reversal of trend. So far we have been lucky but who knows when the tide will turn;

-

Geopolitical Risks;

-

Uncertainty over global growth conditions;

-

Uncertainty over Southwest monsoon. India is primarily an agricultural country. The contribution of agriculture to GDP has come down to around 18%. Agriculture is basically driven by the monsoon. It is at the vagaries of the monsoon. That continues to be our concern and the challenge. In our CPI basket, we have a high share of food. If the monsoon turns bad, food prices go up and the inflation target will go;

-

High food inflation. This is also a threat for Indonesia; and

-

Likely slippage in fiscal deficit target.

Interaction

- Participant::

-

There is high demand for loans for the government. The government is demanding too much financing. Fiscal policy is now demand high to finance numerous projects. How does the central bank deal with that? The fiscal budget is very high to finance projects and how does the RBI deal with that? I checked and it seems the biggest problem in India is on the fiscal side. Interest is very high, growth is low and inflation is very high. India is facing something. How about NPL? A recent report has shown an increase in bad loans, which is also an economic indicator.

- Speaker::

-

They have their own financing sources. They are raising their own resources from the market. At the same time, the government is also mobilizing resources through the ‘Made in India’ program. Our current prime minister is very dynamic and has come up with many schemes to mobilize capital from various sources. Although I mentioned the huge borrowing program, our domestic debt is at a very low level compared to other countries.

Non-performing loans are a major problem in India, but they have just started coming down recently because of the regulatory steps we have undertaken. We now have some harsh draconian legislation in place, namely that the banks are fully entitled to acquire your assets the moment you default. Earlier, that was not the case, but the banks have now been given full power through a legislated mandate. The Indian Government is trying with the UK Government to get Vijay Mallya extradited to India because he has defaulted on many things. Recent legislation has given these powers. I am just giving an example, this is not to name anybody.

- Participant::

-

How is the yield curve of your government bonds? For infrastructure development, we need longer-term government bonds, right? How do you define financial system stability? Do you have a central committee? Is RBI still lender of last resort?

- Speaker::

-

In 2018, it had become quite steep but now it has come down a bit because of other domestic factors. In India, it is inflation. Inflation is quite low now; the current account deficit is low and monetary policy is in easing mode so the yield curve is flatter. You are right though, in 2018 the yield curve was quite steep because of global factors, such as crude oil prices, trade war concerns, geopolitical tensions and the US Federal Reserve increased its policy rate. We have a Financial Stability and Development Council in India—in Indonesia, this is shared with the finance minister—but RBI has an important role to play there because we are regulating and supervising the banking system. RBI is still the lender of last resort. There are other stakeholders, including the insurance regulator and stock market regulator, but the Reserve Bank has a major say in financial stability because financial intermediation mainly (80%) takes place in India through the banks, which are regulated and supervised by the Reserve Bank. Actually, the Reserve Bank has more say in terms of financial stability.

- Participant::

-

Have you started implementation of International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS)? For us in Oman, after IFRS implementation, we had an issue of increasing non-performing loans. Is it the same in India due to the changes in the accounting and reporting part? Which sectors in India our expanding currently? Which sector is doing better? If it is the services sector, it is an issue because although it helps India create more jobs it is not as good as manufacturing because manufacturing can give you more FX growth. The services sector provides more jobs.

- Speaker::

-

India will begin IFRS implementation shortly. Banks have been given the models and we expect the NPL to show up higher. There are many accounting problems. We are first preparing the banks for this new reporting format because they are not used to it. In India, the services sector is currently expanding. You are saying that the services sector can give notional growth but manufacturing is what is really going to add to your national production. India is an IT hub, including electronics and software. Having said that, manufacturing is not doing badly either. Manufacturing is doing well but not to the extent of services.

- Participant::

-

I have a question about the differentiated risk weights. How do you determine the sensitive sectors? Which variables are you following for these sectors to determine that they are sensitive?

- Speaker::

-

RBI has categorized some sectors going by the volatility in their asset prices, especially commodities, commercial real estate and housing. These are the sensitive sectors in India.

- Participant::

-

Regarding the interaction between macroprudential and monetary policies. You said there is some sort of coordination between the two policies, I was wondering whether it is coincidental coordination? If it is calibrated coordination, how was it calibrated? Was it by virtue of the governor deciding both or is there some sort of committee? Are all macroprudential policies taken by the FSDC now?

- Speaker::

-

It was calibrated coordination. The coordination that I mentioned earlier happened before the Financial Stability and Development Council was established. Financial system stability was only looked at by the central bank. At that time, coordination was easy because the policies were taken by the Reserve Bank. Even now, coordination is still being done because the governor of RBI is always present at major policy decisions and whatever policy decisions are taken by the FSDC, they are done in close consultation with the governor. All macroprudential policies are taken by the FSDC now but the Reserve Bank has a major say because macroprudential policies mean you have to apply regulations on banks and the central bank is responsible for regulating the banks. It is the central bank that applies the ratios. The announcement is made by the FSDC but the regulations are applied by the central bank, which is done in close coordination. It is the same case in Malaysia.

- Participant::

-

What is the average capital adequacy ratio of banks in India? How are the banks doing in terms of capitalization as well as short and long-term liquidity?

- Speaker::

-

The minimum CAR prescribed by Basel is 8% but in India it is 9%. Nevertheless, banks in India tend to hover around 11%. As far as the liquidity coverage ratio is concerned, the one thing that really came in handy for the Reserve Bank was the statutory liquidity ratio. That may be unique to India. As per that ratio, all the banks had to necessarily invest in government securities, which made that ratio. It used to be 30% but now it has been reduced to 19.5% of net demand of total liabilities of banks. Now banks are investing in government securities in the statutory liquidity ratio, yet to meet the LCR requirements, the Reserve Bank has given them the concession to make use of that ratio, up to 11%, to meet the LCR requirements because it is high-quality collateral/liquid assets.

- Participant::

-

By giving emergency liquidity assistance to banks, does the Reserve Bank of India have a limit or threshold on the level of risk for the bank that is going to be given the ELA? Are there certain requirements before giving the emergency liquidity assistance to the banks?

- Speaker::

-

We do not have any such requirements. On a day-to-day basis, we have a 1% limit in terms of the total liabilities of the banking system. 25% is provided under fixed rate auctions and the remaining 75% is provided under variable rate auctions. During the crisis, although India was not directly impacted by the global financial crisis, the country was impacted by indirect effects and knock-on effects, which put the banks under liquidity pressure. Consequently, RBI opened up special windows for them for additional liquidity with no such limits because we know their financials. The banks are well regulated and supervised by RBI so there is no question of putting any limits on them because all of their investments are with us.

- Participant::

-

India has quite a high current account deficit. Do you have any plans to reduce the deficit?

- Speaker::

-

Last year it was 1.8% but because of the capital outflows and high trade deficit, this year it has gone to 2.6%. The empirical studies in India have shown that a sustainable threshold is around 2.5%. Consequently, the intention is always to bring the current account deficit down. For emerging countries like India, however, it is better to have some deficit than to have a negative interest rate policy.

- Participant::

-

India has increased and cut its policy rate within the last year. Have you observed any asymmetry in the transmission of monetary policy given the changing direction of monetary policy? Are banks prone to increasing their rates when the policy rate is increased but then reluctant to reduce rates the other way? How do you convince foreign banks to lower their rates?

- Speaker::

-

As with all central banks, during a tightening phase, the banks are quick to respond. During an easing phase, however, they are quite reluctant. Once they have raised the rates, the downward stickiness is always there. The Governor of the Reserve Bank and the Minister of Finance try to persuade them at the various meetings. They inform the banks that they must pass the rate cuts to the customer. Bank managers always have their own excuses, such as deteriorating asset quality or higher transaction costs. Foreign banks also see that this is a competitive world, if they want to be in the market, they have to go with the tide.

Macroprudential Regulations

India started using macroprudential regulations in 2004. In fact, RBI was a pioneer and one of the first central banks to use macroprudential tools, which became more popular after the crisis. The measures RBI has include countercyclical provisioning, loan-to-asset value ratios and risk weights, particularly on housing and commercial real estate. This has been done in close coordination with monetary policy. Between 2004 and 2008, monetary policy was in tightening mode, and because that was a high growth and high credit period, the provisioning norms and countercyclical norms were also tightened. Monetary policy was tightened by increasing the policy rate by 300 basis points. At the same time, the provisioning norms were increased by 175 bps and 25 bps. From 2008 to 2009, monetary policy entered an easing phase and the macroprudential policy was also loosened. They were working in close coordination and as far as the effectiveness of these policies is concerned, a recent empirical study in the RBI showed that these risk weights and countercyclical provisioning norms were effective at containing the credit growth. They negatively affected credit growth with a one-year lag. There is an asymmetric impact, in terms of the macroprudential regulations on different credit cycles for different business cycles. They are more effective in containing credit growth, this means that they are unable to stimulate credit growth when it is low. This means, the macroprudential measures are effective during an upward cycle but ineffective during a downward cycle.

Interaction

- Participant::

-

What is your instrument for the interest-rate policy? Is it the repo rate?

- Speaker::

-

The repo rate is the single policy instrument.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this license to share adapted material derived from this chapter or parts of it.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 BI Institute

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Prakash, A., Lokare, S.M. (2022). Reserve Bank of India Policy Mix. In: Warjiyo, P., Juhro, S.M. (eds) Central Bank Policy Mix: Issues, Challenges, and Policy Responses. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-6827-2_10

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-6827-2_10

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-16-6826-5

Online ISBN: 978-981-16-6827-2

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)