Abstract

An important driving force for the rapid development of China’s economy is rapid urbanization. In 1949, only 10.6% of China’s population lived in cities. In 2019, China’s urbanization level reached 60.6%. According to the experience of industrialized countries, it is estimated that by 2035, about 70% of China’s population will live in urban areas. In 2050, this proportion will rise to around 80%.

*Part of this thematic policy study report has been published. Refer to: Zhang [1].

Please pay attention that the main body of this chapter has been published in Chinese Journal of Urban and Environmental Studies https://doi.org/10.1142/S2345748121500019

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

4.1 Why Is the Green Urbanization Transition So Critical

4.1.1 The Basic Tasks for China’s Urbanization

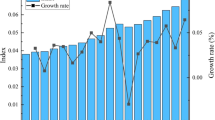

An important driving force for the rapid development of China’s economy is rapid urbanization. In 1949, only 10.6% of China’s population lived in cities. In 2019, China’s urbanization level reached 60.6% [2]. According to the experience of industrialized countries, it is estimated that by 2035, about 70% of China’s population will live in urban areas. In 2050, this proportion will rise to around 80% (Fig. 4.1). The National Population Development Plan (2016–2030) predicts that China’s total population is expected to reach 1.45 billion by 2030, which will gradually decline afterwards. The urbanization rate will be 70% at that time. The United Nations Population Division also predicts that China’s population will peak around 2030, and would decrease to 1.4 billion by 2050 [3]. This means that China’s urbanization level still has about 20% points to increase, and the newly added urban population is about 200 million people.Footnote 1

Therefore, China’s green urbanization faces two basic tasks: first, how will the 300 million people be urbanized in a green way; second, how will the existing cities formed in the era of traditional industrialization become sustainable through a green transformation that injects vigour into the economy.

To answer these two questions, it is better to understand the nature of urbanization. The agglomeration process of population and economic activities in cities, i.e., urbanization, has greatly accelerated the process of industrialization. Human society has thus formed a modern social structure based on industrial civilization and the basic urban–rural economic geography of “urban–industry and rural–agriculture.” Therefore, urbanization has long been regarded as an important driver for economic growth. However, there are problems with modern cities, and environmental pollution is one of the most severe problems. That is why green urbanization is so currently important.

4.1.2 The Basic Characteristics and Consequences of Traditional Urbanization

Historically, it took a long time for cities to emerge, but large-scale urbanization is a product of the Industrial Revolution.

The urbanization that took place in the traditional industrial era has two basic characteristics:

First, from the perspective of economic development, the function of the city is mainly to promote the production and consumption of industrial wealth, i.e., to promote the process of industrialization. Correspondingly, the function of urban infrastructure is also largely to facilitate the production of industrial products. More generally, the economic development process based on traditional industrialization is a process of urbanization that transfers a large amount of agricultural labour to urban manufacturing, forming a pattern of urban–rural economic geography of “urban–industry; rural–agriculture.”

Second, the organization of the city itself is mainly based on the centralized logic of traditional industrialization. The city’s design philosophy relies too much on industrial technology, rather than relying on ecological ideas to make nature work for the benefit of humanity. For example, heating, energy, construction, water treatment, etc., are often costly. Fully tapping natural forces will reduce the costs of the city and increase its efficiency (see The Nature Conservancy, “Valuing Nature’s Role”).

This urbanization model, while greatly promoted industrialization, inevitably brings unsustainable consequences to the environment and the regional economy.

First, it results in serious environmental consequences, including air pollution, water pollution, noise pollution, and solid waste pollution, etc. This is because the traditional industrialization model centred on the production and consumption of material wealth must be based on material consumerism (e.g., encouraging overconsumption, planned obsolescence, instant products, etc.), resulting in “excessive resource use, severe environmental damage, high-carbon emissions.” If economic growth still heavily depends on the material wealth, urbanization based on this will inevitably become a major source of environmental problems.

Second, the transformation of traditional agriculture into industrialized and chemical agriculture with the logic of urban industrialization has brought about serious rural ecological and environmental consequences, including environmental pollution (industrial pollution, chemical agriculture, aquaculture pollution, domestic pollution), ecological consequences caused by overmining, ecological chain destruction, monoculture, and chemical agriculture.

Third, the consequences of urban–rural and regional imbalance. In the process of industrialization and urbanization, the population will migrate from rural areas that have no industrial advantages to urban or coastal areas, which will bring irreversible impact to the former and inevitably lead to urban–rural and regional disparities.

Fourth, social and cultural costs. On one hand, there appears to be modern social diseases in big cities, where high income and low well-being have become a prominent problem. At the same time, it is difficult for migrant workers to be truly integrated into the city. On the other hand, urban and rural problems have become two sides of one coin. The original rural social fabric has been impacted by large-scale urbanization. The problem of “agriculture, rural areas, and farmers” has become serious, and a large number of hollow villages, left-behind children etc. have appeared. To this end, the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China has made “rural revitalization” a major strategy.

As the basis of the traditional urbanization model, the traditional growth model has significantly enhanced human well-being, while also affecting people’s well-being through two channels. First, ecological damage and environmental pollution will reduce people’s quality of life and well-being. Environmental problems such as air pollution, food safety, water contamination, noise, extreme weather, and biodiversity loss have penetrated all aspects of people’s lives, seriously affecting their quality of life, health and safety (for example, [4]). Second, economic growth centred on the production and consumption of material wealth has failed to simultaneously improve people’s quality of life and happiness. Numerous studies have shown that in many countries, including China, economic development under the traditional industrialization model does not continuously improve the level of happiness in the way people think [5,6,7,8,9]. When basic material needs are met, the further expansion of material wealth, although it will bring bright GDP figures, will have little effect on improving people’s well-being. Meanwhile, the so-called modern way of living compatible with the industrial model brings about the disease of affluence.

In short, the traditional industrialization model, which is the basis of the existing urbanization, has brought about high material productivity, but it is unsustainable with high costs. Since these high costs are not reflected in the internal cost of enterprises but reflected as social costs, hidden costs, long-term costs and opportunity costs, they are easily ignored. At the same time, the well-being this growth model brings is also relatively low, while improving well-being is the ultimate purpose of economic growth. With the transformation of this unsustainable growth model to sustainability, the corresponding urbanization model must also be redefined on the basis of ecological civilization.

4.2 Green Urbanization: An Analytical Framework

4.2.1 The Theories Regarding Green Urbanization

There are two popular theories regarding green urbanization or sustainable urban development [10], but it seems hard for them to solve the fundamental problems of urbanization because they fail to think outside the traditional industrial box.

The first is to understand development issues and urbanization based on traditional industrialization thinking. In this model, cities represent opportunities, and economic development is the process of continuous population transfer to cities. Population concentration is conducive to economies of scale and technological innovation, so the larger the city is, the better it would be. Unsustainable issues such as the environment in cities can be addressed through technological advances and better urban design. Quite a few mainstream urban thinkers, especially economists, can be classified as such [11,12,13,14,15]. Some scholars believe that although many urban problems arise because of their large scale, the resolution of these problems also depends on the size of the city [16]. This thinking does not think (or fails to realize) that behind the problem of urban unsustainability, the essence is the unsustainable development model. As Einstein pointed out, “We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them.” Another related idea is to advocate the path of small and medium-sized towns. This kind of thinking makes natural sense. The biggest problem here is that whether the emphasis is on the path of large cities or the paths of small and medium-sized towns, it is a pseudo-problem, because the fundamental driving force behind the size of the city is market forces rather than administrative planning. No force can design a city in advance, whatever its size.

The second is to emphasize the ecological and environmental capacity of green urbanization, and to emphasize that the development or scale of a city should be planned scientifically in accordance with local resources and environmental capacity. This statement is widely accepted and it seems reasonable because it is impossible for any city to exceed its environmental capacity—which seems self-evident. However, when the development content carried by a city and its organization changes, its corresponding environmental capacity will also change. The same environmental capacity can accommodate different city sizes. This urbanization approach is essentially the same as the first one that emphasizes technology, because given the constant development content, economic development must rely on technological breakthroughs; otherwise, environmental capacity will restrict economic development.

These popular ideas are, to a large extent, discussing green urbanization in the framework of traditional industrialization. Since modern economic activity mainly occurs in cities, most of the environmental problems also originate in cities. In this way, people naturally treat green urbanization as an urban issue rather than a development issue, and take existing towns as a starting point for discussion.

However, the environmental problem of a city is, in its nature, an issue of the development model, rather than the problem of the city itself. When the content and methods of economic development—which are the basis of urbanization—face a profound transformation because they are not sustainable, the corresponding urbanization model must also undergo a profound transformation. When people discuss ecological civilization, they often talk about the so-called “Green Industrial Civilization,” that is, achieving the goal of sustainable development through green technological innovation without changing the traditional industrialization model [17]. However, Green Industrial Civilization is not an ecological civilization, and the two are essentially different [18].

The existing urbanization model, whether it is the economic content carried by the city or the specific organizational form of the city itself, is largely based on the logic of traditional industrialization. This development model has brought great progress to humankind, but also brought serious unsustainable problems.

Urbanization is a spatial manifestation of economic development. When the technical conditions and content of economic development change, the spatial form they require will change accordingly. Therefore, urbanization does not always increase productivity. Although the emergence of cities has a history of thousands of years, the phenomenon of large-scale urbanization in the modern sense is based on the industrialization model formed after the Industrial Revolution. In the agricultural era, cities were more used as political, religious, military, and other non-economic centres. Because agricultural activities depend on land, large-scale urbanization in the agricultural era cannot increase but reduce productivity.

Therefore, when thinking about green urbanization, we should proceed from the starting point of why cities exist, rather than starting from existing cities and towns. The environmental problem of a city is fundamentally an issue of development model, not just a problem of the city itself.

This means that on the basis of ecological civilization, the existing urbanization must be reshaped, and green urbanization promotes China’s economic transformation and high-quality development.

4.2.2 Analytical Framework

Thinking about green transformation of urbanization must begin with the question of why there is a city. Before answering this question, we must first understand the mechanism of economic growth and how urbanization promotes economic growth.

The driver of economic growth is the improvement of the division of labour, and the division of labour is limited by the extent of the market [19]. There is a trade-off here, that is, a higher specialization and division of labour mean higher productivity, but the division of labour necessarily requires trade, which incurs transaction costs. If the transaction costs are too high to exceed the benefits of specialization and the division of labour, it would be difficult for the division of labour to occur and for the economy to grow [20, 21].

Therefore, how to increase transaction efficiency is the key to promoting economic growth. Urbanization is crucial for increasing transaction efficiency. In addition to the improvement of (i) hardware infrastructure such as road transportation and communication and (ii) the soft aspects of institutional and mechanism design (including effective government, property rights system, enterprise system, patent system, etc.), the geographic agglomeration of economic activities in urban areas—i.e., urbanization—plays a crucial role in increasing transaction efficiency.

Because an industrial chain is concentrated in the city, it is easier to develop the division of labour and collaboration compared to being scattered in rural areas, thus driving economic growth. The other benefits of the city include: First, the agglomeration of the population in the city can expand the market, which creates conditions for the increase of the division of labour. Second, the centralization of urban facilitates the provision of infrastructure and government public services. The concentration of public facilities such as water, electricity, gas, and communications would, compared to decentralized provision, greatly improve the efficiency of use and reduce construction costs. Third, the concentration of population in cities facilitates the exchange of ideas and is conducive to the creation and diffusion of innovation and new knowledge. In addition to the perspective of division of labour, there are many other perspectives in urban research [12, 22,23,24,25].

Therefore, there are three key factors determining the urbanization model: The first is the change in transaction efficiency; the second is the change in the provision of public facilities and public services; the third is the change in the content of development, i.e., the content of production, consumption, and trading. Among them, the development content shifts from the industrial wealth characterized by “high resource consumption, high environmental damage and high carbon emissions” to high-quality service industries that rely more on intangible resources such as knowledge, eco-environment, and culture. When the three defining factors undergo profound changes, the requirements for spatial agglomeration of economic development will change, and the content and forms of urbanization will also change accordingly. A core objective of this research is to investigate the changes of these defining factors in the digital and green development era and its implications for China’s urbanization, and how the government should formulate corresponding green urbanization strategies (Fig. 4.2).

4.2.3 The Emergence of Urban Clusters

Now that the agglomeration of population and economic activity is so important to economic growth, according to this logic, should the entire population gather in a super-large city? The answer is no. Driven by market forces, a hierarchical structure of large, medium-sized, and small cities will be formed, and then several central cities will be formed in different regions, which together constitute several urban clusters and metropolitan areas.

Why is there a hierarchy of large, medium-sized and small cities? Although big cities improve productivity, they also have disadvantages, including high prices and various “urban diseases” in terms of urban pollution, traffic congestion, high housing prices, crime, high mental stress, etc. Therefore, the real utility in big cities is not as high as their nominal income suggests. For example, a 10,000-yuan income in a big city does not mean that its real utility is twice that of a small city of 5000 yuan, because a large part of the income is used to pay for various costs including transport, high rent, and so on. If further taking non-monetary factors such as pollution and pressure into account, the real utility of big cities and small cities should be quite similar. This is why, under strictly market forces, different people will choose different cities to work and live, thus forming a hierarchical structure of large, medium-sized and small cities [25].

How do the urban clusters appear then? The reason is that different regions forming their central cites can minimize the spatial cost of the overall economy. In particular, a vast country with a dense population like China will certainly form a number of regional central cities and metropolitan areas, and within each of them will form a hierarchical city structure. The phenomenon that a large part of a country’s population is concentrated in a mega city is more likely to occur in territorially small countries. The total transaction costs of the population to agglomerate in different central cities are often lower than that of the entire population agglomerating in a single large city. In addition to cost, how cities are geographically distributed also depends on the benefits of agglomeration to production, which is affected by land area, population size and initial distribution, industrial structure, natural endowments, transportation, climate, culture, institution, and etc. Such factors affect the cost and benefits of agglomeration and thus affect the geographical pattern of urbanization.

4.3 The Future Green Urbanization Model in China

4.3.1 The Key Factors Defining Urbanization Are Changing

As human society enters the digital and green era from the traditional industrial era, the three key factors that determine the urbanization model are undergoing dramatic changes. These changes are particularly dramatic in China. This means that China’s future urbanization model will undergo profound changes.

First, there has been a dramatic increase in transaction efficiency. With the advent of the Internet, the digital age, and the rapid transportation system, the traditional conceptualization of space and time is undergoing major changes. Many economic activities do not necessarily have to rely on the large-scale physical concentration of production factors and markets as in the industrial era, and no longer have to be undertaken in the city or at a fixed location.

Second, technological changes have made it possible for some public facilities and services that originally relied on physical concentration to be provided in a decentralized manner. For example, heating, sewage treatment, distributed energy, garbage disposal, etc., can be transferred from centralized supply to distributed supply in many cases. This means that in some small towns and villages, high-quality living can be achieved at a low cost. In the digital age, many government services are also accessible through digital platforms.

Third, and more importantly, the economic development driver changes. As discussed above, the traditional industrialization model will inevitably lead to an unsustainable environment. One of the important tasks of green urbanization is to change the supply that meets people’s new demands. Among them, increasing demand for the emerging services that meet people’s expectations of a better life is the direction of green development and is the new economic foundation of green urbanization. Although urban agglomeration is still very important, economic development requires less physical concentration than it once did. In particular, rural areas and small towns excel in good environment and culture. As a result, many new economic activities may emerge in the countryside, and the urban–rural relationship will be redefined.

4.3.2 The Implications of Green Urbanization

It is important to point out that although the above changes in the three key factors have made many economic activities less dependent on the physical concentration of the factors of production as in the past, this does not necessarily mean “the decline of the city,” nor does it mean that a large number of economic activities will leave the city. It means the traditional urban and rural concepts need to be redefined through which new sources of economic growth would be emerging.

-

The profound change of economic activities carried by the city. People’s demands for a good life are not just reflected in material wealth. As demands upgrade, the content of economic development expands from traditional material wealth to emerging services. Many economic activities that did not exist under traditional development will appear. For example, the large population of existing cities could be an advantage for developing a culturally creative and experience economy, thus transforming the development content; in addition to producing agricultural products, rural areas could also represent a new type of geospatial space that can accommodate many new economic activities, including economies of experience, ecological tourism, education, health, etc.

-

The change of city’s own organization and geospatial layout. For example, the way of urban life will change a lot; the centralized energy supply may be partially replaced by distributed supply, and urban infrastructure will be based more on ecological principles.

The above changes have the dual effects of increasing agglomeration and decentralization of economic activities. Whether the urban areas will become more agglomerated or decentralized depends on which effects of the above three defining factors become dominant.

4.3.3 Spatial Distribution of Future Urbanization

As for the trend of spatial distribution of urbanization in the future, it seems that a consensus has yet to be reached in the academic community. There are two different visions regarding future urban forms. One is support for the decentralization trend. Henderson et al. show evidence that Chinese cities are experiencing a decentralization trend with the emergence of high-speed rail [26]. Another is that the Internet and convenient transportation will accelerate the concentration of population to large cities, such as [13]. These two different conclusions may be due to different urban theories and different definitions. Therefore, it would be more effective to measure the real situation of urbanization through big data on population and economic activities distribution than traditional statistical data.

For China’s future urbanization strategy, it is very important to clarify the relationship between city size and economic development. Though city scale is emphasized in much of the literature, in the theory of economic growth, population size is not always conducive to economic growth. For example, in Solow’s growth theory, endogenous growth theory, and Lewis’ surplus labour theory, population size has a negative, positive, or neutral effect on economic growth. The new economic geography, represented by Krugman and Fujita [12], emphasizes the benefits of population size for economic growth. However, as [27] pointed out, the “extent of market” emphasized in Smith’s theorem is not “mass production” and population size. Zhang and Zhao [28] show that the economies of scale of enterprises in the Fujita–Krugman urbanization model are not in line with reality. Some empirical studies that emphasized the size of the city show there is a strong correlation between the size and per capita GDP [11]. However, the conclusion may not be that simple, and we explained how the urban hierarchy structure is created earlier. Because large cities have increased market size and a higher level of division of labour, their nominal GDP is usually higher than that of small and medium-sized cities, but the GDP of large cities contains more transaction costs including commuting costs, high house prices, congestion, etc., and so the net utility is not necessarily higher. The regression analysis on urban population and GDP can always lead to the conclusion that the larger the city is, the higher the GDP will be. This conclusion may be misleading from academic and policy perspectives.

In reality, we can find a large number of examples of “small but advanced cities,” and “large-scale but poor cities.” In Europe, more than half of the population lives in small and medium-sized cities with a population of 5000–100,000 [29]. At the same time, the size of the urban population is not equal to prosperity. 22 out of the 29 megacities in the world with more than 10 million people are in Africa, Asia and Latin America, and these super-large cities have not prospered. In China, the development of many cities no longer depends on population growth, and there is an inverted U-shaped relationship between population and urban economic growth [30].

4.3.4 The Evolution of China’s Urbanization

The actual level of urbanization in China is higher than statistics suggest. The urban area is defined as an area with a population density of more than 1000 people per km2. According to a study of DRC Big Data Lab for Macroeconomy with Baidu HUIYAN Population Big Data, China’s actual urbanization level in 2015 was 62.2%, 6.1% points higher than the traditional statistics [31] (Fig. 4.3).

Source Chen and Shi [31]

Comparison of provincial urbanization level: Big data-based and statistics.

Second, China’s cities have entered a high-quality development stage from quantity expansion. Economic development and population in some cities have started to show an inverted U-shaped relationship [32]. Over the past two years, the net inflow of daily migrants in some of China’s most attractive cities has not changed significantly. The resident population in a few megacities has declined. As the regional economy becomes more balanced, an increasing number of people tend to return to their hometowns to work or start a business.

Third, the spatial pattern of the city is undergoing major changes: the rise of urban clusters and metropolitan areas will dominate the future economic development in China. According to the calculations of the SPS team, the proportion of GDP, population and land area in 2017 in China’s 20 urban clusters accounted for 90.87%, 73.63%, and 32.67% of the nation, respectively. Lan Zongmin’s research, based on Baidu migration data, mobile phone density data and nighttime lighting data, showed that the divergence of urban clusters is obvious, and the spatial scope of the planned urban clusters is generally smaller than that measured with big data [33].

This means that in the future, the main spatial scope of green urbanization will occur mainly in the existing urban clusters and at the county level. At the same time, the content and form of urbanization are undergoing profound changes.

4.4 The Impact of Green Urbanization on Regional Integrated Development

Green urbanization in the digital age will profoundly change China’s regional economic structure. In the era of traditional agriculture, economic development was highly dependent on natural conditions, so a population distribution pattern was formed based on natural and geographical conditions. In China, there is the so-called Hu Huanyong Line. In 1935, geographer Hu Huanyong proposed the “Aihui–Tengchong Line, and internationally as the Hu line” in the dissertation “Distribution of Chinese Population,” and found that the population west of this line represents 6% of China’s total population and the population east of this line about 94% of China’s total population. This line was later called “Hu Huanyong Line” by academics. According to the “Urban Development Trends” data of the East China Normal University Urban Development Institute, previous census data show that in the 80 years since 1935, China’s population distribution pattern has remained almost unchanged (quoted from “Baidu Encyclopedia”).

This population distribution pattern also provides different conditions for industrialization in the North and South regions. Overall, this pattern of population and economic development has been further strengthened in the industrial era. However, because industrial production can be largely freed from the constraints of natural geographical conditions, and the accumulation of population, that is, the process of urbanization, has greatly accelerated the process of industrialization, and urbanization has increased regional economic differentiation. Industrialization requires support from convenient transportation and markets. Many areas that thrived in the agricultural age no longer have advantages in the industrial age. A large number of agricultural populations and populations in areas without industrial advantages have flowed on a large scale to large and medium-sized coastal cities with industrial advantages. Therefore, development based on the industrialization model will inevitably bring regional disparities in urban and rural areas along with regional economic differentiation. What’s more serious is that this traditional industrialization model not only brings about differentiated development levels, but also the systematic destruction of the socioeconomic ecosystems of backward areas and villages. This is why many rural areas declined during the industrialization process.

As human society enters the era of mobile Internet and ecological civilization, the development paradigm formed in the traditional industrial era is undergoing profound changes, including the development concept, development content, and resource concept, and the spatial meaning of economic activities is also undergoing profound changes. This is expected to fundamentally change this urban–rural imbalance and regional imbalance. This means that although the spatial differences in the sense of natural geography will persist for a long time, the gap in spatial development in the sense of economic geography may break through from a larger space and time range. Therefore, it offers the western regions a good opportunity to follow a path of ecological civilization with a new paradigm shift in the digital era.

Specifically, it is green urbanization that is changing the spatial pattern of the regional economy. The combination of “green” and “urbanization” has special significance. Meanwhile, urbanization can drive economic growth by reshaping the spatial pattern where population and economic activities concentrate. Green is an important factor to meet the needs of a better life. Its corresponding resource concept goes beyond the concept of material resources underlying traditional industrial civilization and is closely related to the ecological environment and culture which is the endowment of the backward regions. Therefore, from the perspective of green development, the endowment concept of the regional economy will be redefined. This will bring new opportunities to the backward areas that lack development advantages in the industrial age.

4.5 Green Urbanization: Case Studies

There are many good practices in China and around the world in promoting green urbanization. How to select valuable cases for research is the first problem to be solved by case studies. Einstein has famously said that “It is the theory which determines what we can observe.” In the face of the complicated real world, we cannot simply collect random cases for research, but we must step out of the traditional industrialization model and identify valuable cases based on new theories and concepts. Specifically, we hope to discover and even create valuable cases by participating in local experiments under the new green urbanization theory framework. The difficulty is that due to path dependence, the realization of the theoretical vision often faces the “chicken and egg” dilemma. When there is not enough evidence for green urbanization, governments often do not take strong action to avoid the risk of failure. The evidence is less likely to occur without sufficient action. Therefore, we cannot judge the feasibility of green urbanization based on whether there are enough successful cases of green urbanization. The principle of evidence-based decision making is not always reliable for the transformation of the development paradigm. In many cases, the foresight and action of decision-makers are often more critical.

4.5.1 Cases in China

Case 1. Shenzhen New Energy Transportation (National Climate Assessment Report 2019)

Shenzhen is the first batch of demonstration cities for the application and promotion of new energy vehicles in China and has become the city with the highest number of new energy vehicles in the world. As of July 31, 2018, the number of motor vehicles in Shenzhen was 3.3307 million, of which the number of new energy vehicles reached 187,100, accounting for 5.6% of the total. By the end of 2018, Shenzhen had realized electrification of all buses and taxis. The value of this case is that many obstacles to the promotion of new energy vehicles can be solved through a series of policies and mechanism designs.

The measures taken by Shenzhen are as follows. First is to resolve financial pressure. In order to solve the problems of the promotion of new energy vehicles in the face of their relatively high purchase prices—along with the mismatch between power battery life and vehicle service life—Shenzhen has adopted a “financial lease, vehicle-electricity separation, and combination of charging and maintenance” model. Second is to innovate the promotion and application model, prioritize public transport, and initially realize the combination of asset light-weighting, rent-purchase, mileage guarantee, hire payment in installments, self-charging, and benefit sharing. Third is to focus on providing financial support to charging facilities. On the basis of a network of charging facilities combining fast and slow charging, it has continuously innovated and diversified charging methods. Fourth is to promote the development of the new energy vehicle industry, a number of industry leaders such as BYD, Wuzhou Long, and Waterma have emerged, forming the most complete new energy vehicle industry chain in China.

Case 2: Shenzhen’s Coordinated Governance of Air Quality and Carbon Emissions (National Climate Assessment Report 2019)

Protecting the blue sky and addressing climate change are two major challenges facing China, and emissions of air pollutants and carbon emissions have the “same roots” to a certain extent, which can be attributed to the burning of fossil fuels and production of steel and cement. Therefore, there is a synergy in reducing air pollutants and carbon emissions. From the perspective of emission sources, the focus of Shenzhen’s air pollution prevention and carbon emissions is on transportation. At present, Shenzhen has implemented measures in the field of transportation. According to a 2015 study by Peking University Shenzhen Graduate School and Shenzhen Comprehensive Transportation Operation Command Center, the proportion of new energy vehicles is one of the main controlling factors for the development of urban low-carbon transportation. The value of this case is that the benefits of reducing carbon emissions are not just global, but are felt at the local level, so reducing emissions can be a self-serving behaviour.

Case 3: Zero-Waste Pilot Cities

In January 2019, State Council issued the Zero-Waste City Construction Pilot Program. Zero waste does not mean that there is no solid waste generated, nor does it mean that solid waste can be fully utilized as a resource, but aims to ultimately achieve the goal of minimizing the amount of solid waste generated in the whole city, maximizing the use of resources, and ensuring the safety of disposal. At the present stage, we should make overall plans for solid waste management in economic and social development through piloting, vigorously promoting source reduction, resource-based utilization and harmless disposal, resolutely curbing illegal transfer and dumping, exploring and establishing a quantitative index system, summarizing the pilot experience, and forming a replicable and applicable construction model. On April 30, 2019, the Ministry of Ecology and Environment announced 11 zero-waste pilot cities, including Shenzhen, Baotou City in Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, Tongling City in Anhui Province, Weihai City in Shandong Province, Chongqing Municipality (main city area), Shaoxing City in Zhejiang Province, Sanya City in Hainan Province, Xuchang City in Henan Province, Xuzhou City in Jiangsu Province, Panjin City in Liaoning Province, Xining City in Qinghai Province.

The green urbanization SPS studies the mechanism behind the zero-waste city and reveals its policy implications. Research shows that, although technically all garbage and waste can be called “gold in the wrong place,” effectively converting it into gold depends on whether it is cost-effective. Being technically feasible doesn’t necessarily mean economically feasible. However, there are many ways to promote the consistency of technical effectiveness and economic effectiveness. For example, we can strengthen the requirements for waste disposal (the “polluter pays” principle), and make related manufacturers concentrate geographically as much as possible. For each pilot city, there are specific constraints, and different measures need to be taken.

Case 4: Chengdu Private Car Carbon Emission Trading System (National Climate Assessment Report 2019)

Chengdu Rong e-Travel carbon project aims to encourage private car owners to stop driving to reduce emissions. By establishing a quantitative methodology for carbon emission reduction, we can quantify the actual contribution of citizens who stop driving vehicles to carbon emission reduction and provide a scientific basis for the “carbon assets” rights and interests of carbon participants. As of October 2018, the number of registered users of “Rong e-Travel” reached 2.03 million, and 16,000 private car owners have voluntarily stopped driving to reduce emissions. Each private car stopped driving on average 14 days, and the total emission of major pollutants has been reduced by about 13 tons. The value of this case lies in that an effective incentive mechanism plays a great role in promoting green consumption mode.

Case 5: Old City Culture Revitalization

The case is about the “four seasons market” in Dali, Yunnan Province. This case will activate an old vegetable market that can’t realize its value under traditional industrial thinking, and produce good economic and social benefits. Because traditional industrialization is based on material wealth, and the industrial production process needs more input of material resources, intangible culture is not only difficult to find a role in production processes, but is also destroyed in the industrialization model. For example, in industrial thinking, the function of the old vegetable market is to sell vegetables. In the process of urban reconstruction, such places are often demolished. However, once we jump out of this traditional thinking, we can see that the old vegetable market has great historical value and cultural value besides selling vegetables. Through the activation of entrepreneurs, designers, and artists, these cultural values can become new products and services.

However, unlike tangible industrial products, culture is often difficult to trade, and not easy to commercialize. If it can’t be commercialized, it usually depends on government investment, and the government usually has a lot of rigid expenditure, which makes it difficult to take into account such projects that are difficult to bring direct financial revenue. At this time, the new business model is very important for cultural development. One potential business model is that an enterprise take responsibility for the cultural development of a specific region. These cultural services inspire direct transactions, and the development of the region will generate added-value for enterprises in the region, and then the investment enterprise will share part of the benefits from these enterprises and get the return on investment.

The value of this case lies in that it redefines the traditional concept of resources from a new perspective, recognizes the value of culture, promotes its value through creative design and effective business model. This case provides a useful exploration of how to promote those cities formed in the era of traditional industry.

Case 6: Rural Revitalization

Cities and the countryside are two sides of the same coin. The problems of cities will be reflected in the countryside. To discuss the problem of green urbanization, we must discuss the problem of rural development at the same time. Under traditional industrialization thinking, development is defined as the process of industrialization, urbanization and agricultural modernization. In order to produce industrial wealth more efficiently, population and industrial activities need to gather in cities, while rural areas are narrowly positioned as the supply base of surplus labour, agricultural products and raw materials, forming the basic urban–rural division pattern of “urban industry; rural agriculture.” Industrial production activities are based on economies of scale, while agriculture is transformed into so-called industrialized agriculture, mono-agriculture, and chemical agriculture. The process of economic development has become a process of transferring a large percentage of the agricultural population to cities and towns, while other functions of agriculture and villages have not been fully recognized and developed. This kind of development mode has brought a lot of material wealth but has also led to unsustainable well-being, serious urban–rural imbalance, regional imbalances and other problems.

In order to promote the construction of ecological civilization in China, since 2016, the Green Development Research Team of the Development Research Center of the State Council has helped Shishou City in Hubei Province to carry out a green development pilot project. Instead of following the old path of treatment after pollution, it has redefined the countryside with new the development concept and realized leapfrog development through green transformation. In the new development concept and digital era, the countryside is no longer just the traditional definition of the “three rural” concept (rural, farmers, agriculture), but a new geographical space that can carry all kinds of modern civilization and green economic activities. The redefinition of the countryside brings infinite possibilities.

The pilot demonstration mainly focused on four aspects. (1) The chemical agriculture system has been transformed into ecological agriculture on a large scale, and pesticides and chemical fertilizers were no longer used, so as to enhance the value of ecological environment. Their integrated rice–frog–duck farming method has developed the village into the largest rice–duck–frog base in China. The income of villagers has increased significantly, and the rural environment has also improved. (2) Local culture activation: fully explore rich local culture and activate it in modern forms. (3) With the ecological concept, the rural residential areas have been transformed into high-quality ecological communities. (4) Through the new green infrastructure and Internet, a large number of green economic activities that are pro-environment and pro-culture are generated, and the sound ecological environment and rich local culture are turning into invaluable assets, realizing synergies between environmental protection and economic development.” After four years of experiment and demonstration, the region has achieved remarkable progress and explored a new model of rural green development. Officials from developing countries keep coming to study its experience, and some foreign universities even take it as an overseas summer camp base. Shishou has, in this way, become an international knowledge centre for green development.

4.5.2 International Case: Valuing the Role of Nature in Urbanization

So far, the key measures to achieve sustainable cities have focused on how to minimize the environmental hazards that cities can cause. However, these practices still maintain the dichotomy between nature and city. For example, traditional twentieth century environmental protection tools are nature reserves and national parks. An example of the twenty-first century version of the reserve is China’s ambitious national ecological functional area and ecological red lining. These plans extend conservation and restoration efforts to key areas of ecosystem service delivery. However, in fact, these areas are mainly located in rural, mountainous, or sparsely populated areas, which are different from densely populated urban areas. These exclusive nature reserves, of course, are also an important part of the ecological civilization for urban development. However, the benefits of biodiversity and ecosystem conservation have been delivered to cities. We need to integrate nature into urban planning and a value system that covers wastelands to urban cores.

Some cases about how to play the role of nature in urbanization can be found in the Appendix.

-

Greening case of Melbourne metropolis in Australia

-

Greening of the Bay Area of California

-

Bringing life back to Qingxichuan in South Korea

-

Mangrove conservation in the Philippines

-

Rain and flood management case in sponge city of China

-

Providing incentives for urban stormwater management facilities

-

Urban stormwater credit transaction case

-

China Water Conservation Fund

-

How nature becomes an economic driver.

4.6 Strategic Approach to Green Urbanization and Policy Recommendations

4.6.1 Strategic Approach

The overall approach is to reshape China’s urbanization based on the ecological civilization, rather than relying on quantitative urban expansion. Green urbanization should act as a driver for green transition and high-quality development in China, and green urbanization strategy should be an important part of the 14th Five-Year Plan.

4.6.1.1 Three Major Components of Green Urbanization

Component 1: Reshaping Existing Cities, That Is, Transforming Cities According to the Requirements of New Production and Lifestyle in the Digital Green Era

The first is to promote the green new economy. The advantages of existing cities for green transformation lie in demand and supply. In terms of market demand, the existing population size provides huge market for the new service economy; on the supply side, relying on its intangible endowments such as high-quality talents, urban culture, and history, a large number of experience economy and creative economy could be formed. At the same time, it is of great potential to upgrade the traditional sectors by applying new business models and Internet technologies, and China has lots of successful cases, including transformation of old neighbourhoods, old industrial parks, and old malls into creative and experience economic zones, and successful transformation of resource-exhausted cities.

The second is the green transformation of urban infrastructure. Renovating existing urban infrastructure based on the concept of ecological civilization will reduce urban costs and improve efficiency. For example, research by the Nature Conservancy shows that valuing the role of nature brings better results. When ecosystem functions and services are included in a cost–benefit analysis, hybrid infrastructure combining nature-based and traditional infrastructure can provide the most cost-effective protection from sea-level rise, storm surges, and coastal flooding. The traditional flood infrastructure has higher costs and could miss opportunities for generating additional economic benefits and providing ecosystem services that could otherwise be provided by recreation, carbon capture, and habitat (TNC, “Urban Coastal Resilience: Valuing Nature’s Role”).

Component 2: New Urbanization, That Is, Urbanizing New Population in a Green Way

In the future, 300 million people shall be urbanized in a new green concept and model. A large number of these people will be transferred to existing towns, while some will be urbanized locally in the county area to form new characteristic towns. The future between cities and villages is more of a difference in physical form than the difference between modernity and economic development level. Due to the new opportunities in the countryside and the substantial improvement in the quality of rural life, a large number of new urban–rural commuters is likely to emerge. The traditional statistical definition of urbanization also needs to be changed accordingly.

There are many good cases and studies in this regard in China. For example, the Rocky Mountain Institute is promoting “near-zero emission demonstration zones” in some parts of China. It is based on the concept of integrated governance while promoting economic growth, minimizing pollution, garbage and carbon dioxide emissions. The demonstration takes an integrated concept to solve environmental problems, considering the protection of air, water, soil and ecosystem as a whole. It provides an integrated solution from perspectives of the ecosystem, production process, full value chain, etc.

Component 3: A New Definition of the Countryside

The city and the countryside are two sides of one coin. When the content and mode of economic development change, the definition of the village and the urban–rural relationship will change accordingly. Under the traditional concept of development, it is a process in which agricultural labour is transferred to cities for manufacturing on a massive scale—i.e., industrialization and urbanization—while agriculture and rural areas are restructured from the perspective of industrialization, becoming a base of labour, food, and raw materials for use by urban industries. The mode of agricultural production is also transformed into monoculture and chemical agriculture in accordance with the logic of industrialization, which brings serious ecological and environmental consequences. This traditional rural definition from the perspective of industrialization not only limits the economic development potential of the rural areas, but also sacrifices many valuable rural cultural and ecological resources. In fact, the countryside is a versatile new geospatial space that can accommodate a large number of new economic activities. In this regard, China also has many successful cases. For example, the DRC Green Team helps underdeveloped regions achieve leapfrog development through green transformation under the framework of “redefining countryside.”

4.6.1.2 Two Strategic Focuses of Green Urbanization: Green Urban Clusters + County-Level Urbanization

The two strategic focuses of China’s green urbanization are: first, the green transformation of urban clusters and metropolitan areas and second, county-level urbanization. The reasons are as follows.

First, the economy and population of the 20 urban clusters currently account for an absolute proportion in the country. In 2017, China’s 20 urban clusters accounted for 90.87%, 73.63% and 32.67% of the national GDP, population, and land area, respectively. It could be said that the success of the green transition of the whole country hinges on the green transition of its city clusters (Table 4.1; Fig. 4.4).

Second, since the urban clusters include three major components of green urbanization, namely existing cities, population to be urbanized, and rural areas, they can receive both advantages of the urban and rural areas. Focusing on the city clusters and metropolitan areas can activate the advantages of both urban and rural areas and the potential market. Based on their ecological resources, villages located in urban clusters and metropolitan areas could provide new green supplies to the surrounding cities.

Third, revitalizing the county economy is a major task of rural revitalization in China. In addition to moving to the capital city of the county, a large number of people will be urbanized in the form of characteristic towns, so as to take both advantages of the urban and rural areas.

4.6.1.3 Shift from Functional Cities to Pro-nature Cities

The pro-nature urban model is not to divide urban land into different uses, but to integrate the land use so as to incorporate the natural characteristics into the city. In addition, pro-nature cities do not regard nature as an externality but introduce the value of nature into urban planning and decision making while making wise choices to promote public interests. Pro-nature cities can also increase the ecological service supply with the market economy. The challenge is to change the social value system so that natural capital is no longer independent of existing financial systems and land-use planning decisions.

4.6.2 Policy Recommendations

The first recommendation is to achieve a breakthrough in understanding. First, we should fully realize the impact of the current digital era and green development concept on the urbanization model, and we can’t use the old urbanization thinking for green urbanization planning. Second, green urbanization is not just about architecture, planning and green technology, but relates more to development content and development mode. Third, the decisive role of the market in urban planning should be further explored, and the government has a better role to play.

Second is to promote the free flow of urban and rural elements, and the effect of urban planning on rural areas must be taken into account. Cities and the countryside are two sides of the same problem. When it comes to green urbanization planning and policies, we should take an integrated approach and consider its impact on the rural economy, ecology, society and culture. Meanwhile, we should encourage urban talents to move to the countryside and gradually give urban residents access to the lease and use of rural homesteads.

Third is to accelerate the promotion of green technologies. This would begin with the removal of the institutional barriers that hinder the promotion of new green technologies. The biggest obstacle to green urbanization is not a lack of good green technologies—it is the difficulty of implementing them even if they are cost-effective and technically feasible. The next is attaching greater importance to the promotion of low-cost green applicable technologies, such as small constructed wetland sewage treatment systems and passive buildings. The last is to achieve breakthroughs in some green technologies with huge potential and less difficulty, and resolve the application problems. Energy saving by means of room air conditioners is a possible breakthrough.

Fourth is to shift from a functional city to a pro-nature city model. To this end, efforts need to be made in the following four directions (see the Appendix for details). First, we should protect the important urban biodiversity and natural habitats, and to overcome the traditional planning that separates cities from nature. Second, we should integrate biodiversity and ecosystem services into urban planning and design cities with integrated land use, including natural infrastructure essential for human well-being. Third, we should introduce policies and incentives to give value to ecosystem services, and regard ecosystem services as a key part of the market, rather than as externalities. Fourth, we should take the opportunity to provide citizens with ecosystem services as the key to realizing sustainable development.

Notes

- 1.

However, there is a dispute over the prediction of China’s new urbanized population in the future due to great differences in the population forecast by 2050. The emphasis of this report is not to study the newly urbanized population but to illustrate the importance of urbanization.

- 2.

In the long-term collection activities, women understood the law of crop growth and developed agriculture. At the same time, women were responsible for managing residence and raising children. These activities established the leading role of women in the social and economic activities at that time.

References

Zhang, Y. (2020). Promoting China's green urbanization based on ecological civilization—CCICED Report of ‘Green Urbanization Strategy and Pathways towards Regional Integrated Development’. Chinese Journal of Population Resources and Environment, 30(10), 19–27.

National Bureau of Statistics. China Statistical Yearbook 2020 [M]. National Bureau of Statistics Press, (2020). (in Chinese).

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Population Prospects 2019[R]. Online Edition. Rev. 1. (2019).

Yang, J. D., and Zhang, Y.R.: Happiness and Air Pollution[J]. China Economist, 10(5), (2015).

Easterlin, R. A., Morgan, R., Switek, M., & Wang, F.: China’s life satisfaction, 1990–2010[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 109(25), 9775–9780 (2012).

Jackson, T.: Prosperity Without Growth: Foundations for the Economy of Tomorrow. Taylor & Francis, (2016).

Ng, Y. K.: From preference to happiness: Towards a more complete welfare economics[J]. Social Choice & Welfare, 20, 307–350 (2003).

Scitovsky T.: The Joyless Economy: The Psychology of Human Satisfaction [M]. Oxford University Press USA, Revised edition (1992).

Skidelsky, E., & Skidelsky, R.: How much is enough?: money and the good life[M]. Penguin UK (2012).

Zhang, Y.: Redefining Urbanization. Working paper, (2020).

Bettencourt, L. M. A.: The Origins of Scaling in Cities[J]. Science, 340, 1438 (2013). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1235823.

Fujita, M., Krugman, P.: When is the economy monocentric? von Thunen and Chamberlin unified[J]. Regional, Science & Urban Economics 25(4), 505–528 (1995).

Glaeser, E.: Triumph of the city: How our greatest invention makes us richer, smarter, greener, healthier, and happier[M]. Penguin (2011).

Lobo, J. et al.: Urban Science: Integrated Theory from the First Cities to Sustainable Metropolises”[J]. Mansueto Institute for Urban Innovation Research Paper Series, (2020).

Romer, P.: The City as Unit of Analysis (2013). https://paulromer.net/the-city-as-unit-of-analysis/.

Lu, M.: Cities, Regions, and National Development: Current Topics and Future of Spatial Political Economics [J]. Economics (Quarterly), 16(4): 1499-1532(2017). (in Chinese)

Acemoglu, D., P. Aghion, L. Bursztyn, & D. Hemous: The environment and directed technical change[J]. American Economic Review, 102, 131–166 (2012).

Zhang, Y.: Differences between Ecological Civilization and Green Civilization[M]//A Beautiful China: 70 Experts on Ecological Civilization at 70 years of PRC.China Environmental Press Co., (2019a). (in Chinese)

Smith, A.: An inquiry into the nature and causes of the wealth of nations[M]. W. Strahan and T. Cadell, London (1776).

Bettencourt, L. M. A.: Impact of Changing Technology on the Evolution of Complex Informational Networks[J]. Proceedings of the IEEE, 102(12), (2014).

Yang, X. K.: Economics: New classical versus neoclassical frameworks[M]. Blackwell, New York (2001).

Fujita, M.: Urban Economic Theory: Land Use and City Size[M]. Cambridge University Press, New York (1989).

Henderson, J. V.: The Sizes and Types of Cities. American Economic Review, 64, 640–657 (1974).

Yang, X.: Development, Structure Change, and Urbanization[J]. Journal of Development Economics, 34, 199–222 (1991).

Yang, X. and Rice, R.: An Equilibrium Model Endogenizing the Emergence of a Dual Structure between the Urban and Rural Sectors[J]. Journal of Urban Economics, 25, 346–368 (1994).

Baum-Snow, N., Brandt, L., Henderson, J. V., Turner, M. A., & Zhang, Q.: Roads, railroads and decentralization of Chinese cities[J]. Review of Economics and Statistics, 99 (3), 435–448 (2017).

Young, A.: Increasing returns and economic progress[J]. The Economic Journal, 38, 527–542 (1928).

Zhang, Y. & Zhao, X.:Testing the scale effect predicted by the Fujita–Krugman urbanization model”[J]. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 55, 207–222 (2004) .

European Commission: Cities of tomorrow: Challenges, visions, ways forward[R]. EC, Brussels (2011).

Zhuo, X.: A Re-examination of New Trends in Agriculture Population[J]. Shandong Economic Strategy Research, 10, 45–46 (2019). (in Chinese)

Chen, C., Shi, G.: Urban Population Ratio in China from a Big Data Perspective[M]//Demographic Migration and Changing Cities: Urbanization in China from the Lens of Big Data. China Developmental Press, 2019. (in Chinese)

Chen, C., Wei, D..: Analysis of Urban Developmental Potential with Big Data[M]//Demographic Migration and Changing Cities: Urbanization in China from the Lens of Big Data. China Developmental Press, 2019. (in Chinese).

Lan, Z.:Identification of City-Clusters and their Spatial Characteristics with Big Data[M]//Demographic Migration and Changing Cities: Urbanization in China from the Lens of Big Data. China Developmental Press, (2019). (in Chinese).

Hanson, A.: Ecological Civilization in the People’s Republic of China: Values, Action, and Future Needs[R]. ADB East Asia Working Paper Series No. 21, (2019).

Zhang, Y.: Why ecological civilization is different from green industrial civilization [R]. Draft manuscript, (2019b).

Scott, M., & Lennon, M.: Nature-based solutions for the contemporary city[J]. Planning Theory and Practice, 17, 267–300 (2016).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Appendices

Appendix 1: Valuing the Role of Nature in Urbanization and Regional Development

TNC Input to SPS 2-1 Green Urbanization Strategy and Pathways Towards Regional Integrated Development

-

(1)

Introduction

Ecological civilization (eco-civilization) is a set of values and development concepts enshrined in the constitution of the People’s Republic of China in 2018 and now a key driver in the country’s transition to higher quality economic and social development. In an unprecedented fashion, this concept connects the primacy of ecological health with traditional development elements. Explicitly recognizing that people rely on a healthy planet for their economic and social progress, eco-civilization is being used by China to provide a coherent conceptual framework for adjustments to development that meets twenty-first century challenges [34]. With this recent commitment to an eco-civilization development pathway, enormous strides are being made to increase the sustainability of Chinese urban systems. However, to fully transition from our current industrial civilization pathway to eco-civilization, a new paradigm of urban development is needed [35].

-

(2)

Status and Trends

Under industrial civilization, the dominant urban model was what has been called the functional city (Fig. 4.5). In the functional city, nature is thought of as something separate and independent from cities. The functional city was designed with segregated human land uses in discrete zones, with no place for natural features within urban bounds. Moreover, the numerous ways that urban residents and firms depend on nature for their well-being were ignored in decision making and markets. For instance, the clean drinking water of urban residents depends, in part, on natural vegetation preventing erosion into the city’s reservoir. The amount of tree canopy cover there is in a region affects its air quality. Parks and other urban public space contain natural features like lawns, forests, and lakes that are an amenity to people who recreate there. Most ecosystem services that cities rely on are common or public goods. In the functional city model, ecosystem services are considered externalities to markets and decision making. This means they will be degraded and underprovided relative to the true needs of society.

-

(3)

Progress to Date

Steps to make cities more sustainable to date have focused on minimizing the environmental harm cities can do. However, they have retained the sharp dichotomy between nature and cities. For example, the traditional twentieth century tool of conservationists is the protected area, parks and reserves containing important biodiversity set aside from human development. An example of the twenty-first century version of the protected area is China’s ambitious programs of National Ecological Function Zoning and ecological red lines, which extend protection and restoration efforts to areas of key ecosystem service provision. However, in practice these zones are primarily in rural, mountainous or sparsely populated zones, conceived of as distinct from populous, urban areas. These exclusive or near-exclusive nature zones are important components of an eco-civilization approach to urban development, but critical elements of biodiversity and ecosystem benefits occur outside these zones. We need to integrate nature into urban planning and value systems along the full gradient from wild lands to the urban core.

-

(4)

Challenges

To continue China’s transformation into an ecological civilization, we need to move from the functional city model to the biophilic city model (Fig. 4.5). Instead of segregated land use within the city, this model has integrated land uses, which explicitly incorporated natural features within the city. Moreover, instead of treating nature as an externality, the biophilic city brings the value of nature into urban planning and decision making, making wiser choices that promote the public good. Biophilic cities also bring value to ecosystem services in their markets, harnessing the power of market economies to efficiently enhance ecosystem service provision.

The challenge or overall policy directive is to change the societal value structure whereby natural capital is no longer externalized in financial systems and land-use planning decisions. To help achieve this transition, we propose the following four policy recommendations:

-

1.

Conserve important urban biodiversity and natural habitat within urban areas, overcoming the traditional dichotomy in planning between urban and rural areas.

-

2.

Integrate biodiversity and ecosystem services into urban planning, designing cities with integrated land uses that include natural infrastructure crucial for human well-being.

-

3.

Create policy incentives that give value to ecosystem services, treating ecosystem services as a key part of markets rather than as an externality.

-

4.

Use the need to increase ecosystem service provision for urban residents as a sustainable pathway for future economic development in urban, county, and rural areas.

Each of these recommendations is expanded on below.

Source Modified from Scott and Lennon [36]

Conceptual framework for urban transitions from industrial to ecological civilization and internalizing the value of natural capital into financial and land-use decisions.

Opportunities for China: Policy Recommendations for Valuing the Role of Nature in Urbanization and Regional Development

Policy Recommendation 1: Conserve and Restore Urban Biodiversity

-

Recognize urbanization as a key driver of biodiversity loss nationally as well as the importance of urban biodiversity to human well-being. Take global leadership in developing laws, policies, best practices, and measures of success to prevent further loss due to ill-planned urban growth and strengthen the efforts to better protect and restore urban biodiversity in existing cities.

Governance and Implementation

As a party to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), China has committed to protecting biodiversity both for its own value and for its instrumental value, that is, helping solve problems across society, including in and around cities. While China remains one of the most biodiverse countries on Earth, it has experienced significant loss over the centuries. The last 40 years has seen significant loss due to urbanization [36]. Recognizing the significance of biodiversity loss due to urbanization and building on earlier policy directives from the Ministry of Housing and Urban–Rural Development, the China National Biodiversity Conservation Strategy and Action Plan (2011–2030) proposed a planning and demonstration project for biodiversity conservation in urban development. Yet urbanization remains a critical driver of biodiversity loss as reported in China’s Sixth National Report to the CBD Secretariat in 2019.

Beyond treaty commitments and moral motives, biodiversity is also important for its instrumental value, that is, helping solve problems in human communities. Long-term resilience of society, generally, and cities, particularly, require diversity and the conditions where all elements can be present. Sustaining biological diversity is embodied in eco-civilization as a core principle. Preventing loss of natural diversity (and restoring elements already lost) is essential so that we do not foreclose on options to solve challenges faced by future peoples. Historically, most people think there is no biodiversity worth conserving in urban areas, yet we now know that urban nature is an indispensable component of overall biodiversity. Urban areas are important refuges for wildlife, are evolutionary hotspots for novel elements of biodiversity, are key to habitat connectivity across landscapes, and also because nature in urban has much closer interactions with people therefore directly affect people’s lives.

China has recognized that the nature can help solve many urban problems today and created special programs for targeted solutions (i.e., sponge city, national forest city, etc.). But we cannot predict all the challenges cities will face in 50 or 100 years, therefore need all the parts that can help us innovate and create new solutions. Transition from industrial to eco-civilization will not be successful without this.

As China prepares to host the CBD 15th Convention of the Parties in October 2020, we recommend:

-

China should encourage cities to participate in global networks that are creating science-based metrics for evaluating urban systems (municipalities, city clusters, regional rural–urban landscapes) as to their measurable contributions in achieving biodiversity targets of the China Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan and to the CBD, generally.

-

Develop and adaptively strengthen laws and policies for biodiversity conservation in urban systems based on global experience and emerging best practices in China, including standards for (1) cataloging urban biodiversity, (2) preventing loss of extant diversity, (3) strategic restoration of degraded habitats and extirpated species, and (4) conservation programs that engage stakeholders from all sectors.

-

Pilot urban biodiversity improvement programs with clearly defined goals in range of pioneer cities, including tier 1–3 municipalities and city clusters that encompass their regional rural–urban landscapes. An ideal candidate as a demonstration pilot would be the Guangdong-Hongkong-Macau Greater Bay Area. This city cluster and surrounding rural counties lie in the Southeast China Subtropical Broadleaf Evergreen Forest Ecoregion, which globally is projected to have among the greatest loss of biodiversity due to urbanization processes.

Case Studies (Chinese and International Experience and Emerging Best Practices)

-

Greenprinting a Metropolis with Living Melbourne, Australia

-

Greenprinting the Bay Area of California, USA

-

Bringing Life Back to Cheonggyecheon Stream, Korea.

Policy Recommendation 2: Integrate Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services into Urban Planning and Design

-

China should approach cities (including municipalities, city clusters and regional rural–urban landscapes) as a system rather than the implementation of narrow, specific programs on ad hoc basis. To that end, incorporate biodiversity and ecosystem services into China’s new urban spatial planning framework to help better demarcate urban growth boundaries, coordinate the various biodiversity and ecosystem service agencies/programs, and plan for optimizing the value of natural capital along the full land-use gradient.

Governance and Implementation

Seeking synergies across all sectors of society lies at the heart of eco-civilization. For example, protecting or restoring natural habitats in cities will help biodiversity conservation as well as provide ecological services of value to urban settlements, such as abating urban heat, dealing with urban flooding and storm water pollutions, as well as providing recreational green space. Finding synergies is a means to reduce costs while getting better returns on eco-civilization investments. Addressing these synergies can also be a means of improving legal frameworks, financial incentives, and institutional arrangements.

Current urban planning approaches evolved under the industrial civilization model whereby spatial design applied a segregated land-use approach as seen under the lens of socio-technological problem solving (Fig. 4.5). The services nature provides people were externalized from this value system. To make the transition to an eco-civilization we must consider the intersections between ecosystem processes and spatial planning frameworks and consider the city as an integrated socio-ecological system. In other words, internalize the value of nature into urban planning and design. Currently China is designing a new land-use spatial planning system, which already puts a lot of emphasis on ecosystem services. China should keep on this rule within the spatial planning process from national level to city level and help better demarcate urban growth boundaries, especially in newly built cities or towns, to prevent further biodiversity loss due to ill-planned urbanization.

China has made a commitments and established programs to protect biodiversity and maintain ecosystem services. Unfortunately, and reflecting the current state of affairs globally, the approach in China is most typically sectoral isolation instead of synergist integration and codesign. Lost are the obvious advantages gained by treating the multiple benefits of urban nature together instead of as single benefits isolated from each other and planned for separately in space and time. For example, several national programs in China focus on one or a small number of ecosystem benefits such as sponge city, national urban forest city, garden city, and eco-city. There may also be municipal biodiversity conservation plans.

China needs to codify in law and regulation the integration of all overlapping biodiversity and ecosystem service programs in their urban operations and spatial planning. This will result in better outcomes for both biodiversity and people at a spatial scale that matters to the whole rural–urban system and greater economic efficiency in delivering public services.

Case Studies (Chinese and International Experience and Emerging Best Practices)

-

Greenprinting the Bay Area of California, USA

-

Greenprinting a Metropolis with Living Melbourne, Australia

-

Valuing Protective Services of Mangroves in the Philippines

-

Investing in Natural Solutions for Stormwater Management with Sponge Cities, China.

Policy Recommendation 3: Expand Private Sector Engagement and Environmental Markets

-

Through public policy, create incentives that give value to key ecosystem services by establishing new environmental markets that encourage investment by the private sector in natural assets to improve infrastructure and city services. Key to a successful market design is to drive project-based and technology innovation and lowest cost solutions.

Governance and Implementation